The Blohm & Voss Ha-137 is a forgotten also-ran in the dive bomber competition won by the famous Junkers Ju-87 Stuka.

A handful of World War II aircraft took generic names and made them their own. For example, the sobriquet “Flying Fortress,” coined for a number of large bombers bristling with armament, ultimately became the official name of the Boeing B-17. In Russia, Shturmovik simply means “ground attack plane,” but the word came to be associated with the Ilyushin Il-2. Likewise, Stuka—a name derived from the term Sturzkampfflugzeug, or “dive bomber”—is universally accepted as the name of one German airplane, the Junkers Ju-87.

The Ju-87 can be said to have had the monopoly on its name from the moment its blueprints were drawn up as part of the clandestine revival of Germany’s military air arm, the Luftwaffe. Nevertheless, the Germans did go through the pretense of holding a competition and invited Arado and Heinkel to submit their own dive-bomber designs. There was also an unsolicited fourth contender, from a new firm, that had its share of interesting features, even though its chances of success were hopelessly remote.

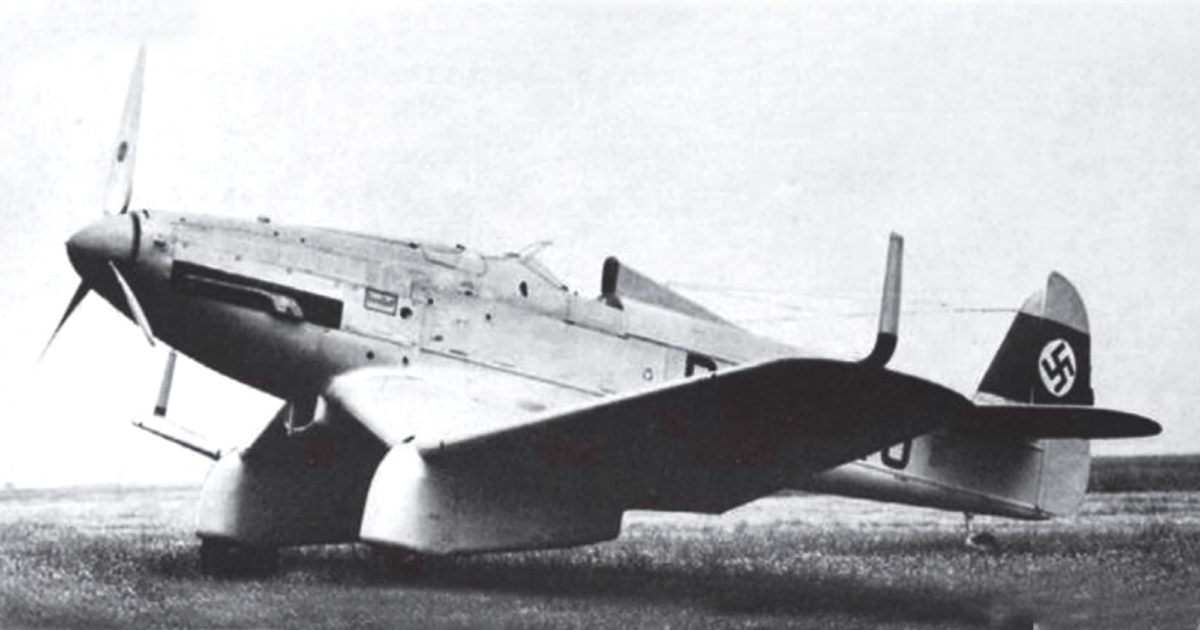

Apart from being a single-seater design with an open cockpit—as compared with the canopy that sheltered the Ju-87’s two crew members—that fourth competitor, the Blohm & Voss Ha-137, bore a remarkable similarity to the Junkers design. The resemblance was strictly coincidental, however. In another coincidence, the Ju-87’s designer, Hermann Pohlmann, joined Blohm & Voss later, in 1940, but the Ha-137’s origin can be traced to another German designer’s work—on a Japanese fighter.

In June 1933, the Japanese army instructed the Kobe-based Kawasaki Aircraft Engineering Company Ltd. to design a radical new low-wing monoplane fighter. Work was initiated by Kawasaki’s chief designer, Takeo Doi, and a visiting German engineer, Dr. Richard Vogt. Vogt’s approach to the project was to incorporate an inverted gull wing to provide better downward visibility to the pilot and also allow a shorter, sturdier undercarriage.

Meanwhile, on July 4, 1933, Germany’s largest shipbuilding firm, the Blohm & Voss Schiffwerft of Hamburg, established an aviation subsidiary, the Hamburger Flugzeugbau (aircraft manufacturer). After producing its first plane, the Ha-135 trainer, chief designer Reinhold Mewes left the firm to work for the Fieseler Flugzeugbau. Vogt was then asked to return to Germany to become chief designer, general manager and part owner of the Hamburger Flugzeugbau.

While he was on his way home aboard SS Europa, Vogt conceived the idea for a novel structural refinement to the inverted gull wing—a single, main load-carrying, tubular spar, located at the thickest point of the wing section and sealed to form a fuel tank.

In Vogt’s absence, Kawasaki completed four prototypes of its experimental Ki.5 fighter. In the course of testing and modification between February and September 1934, the Ki.5 failed to produce the all-around visibility that Vogt predicted and also suffered from poor lateral stability at low speeds. Prudently reverting to a more conservative alternative, Kawasaki went on to mass-produce the Ki.10 biplane fighter in 1935.

Vogt’s first design for the Hamburger Flugzeugbau was the Ha-136, an all-metal advanced trainer, of which two prototypes were built in 1934. Vogt, however, had more ambitious design plans. He had learned that the C-Amt (technical office) of the air travel commission had begun a two-stage project to develop dive bombers for the Luftwaffe, whose existence, in violation of the Versailles Treaty of 1919, was still being kept secret. The first stage of this Sturzbomber-Programm called for the design of a conventional all-metal biplane and resulted in the construction of the Fieseler Fi.98 and Henschel Hs-123; the latter was selected for production in the late summer of 1935. The second phase envisioned the development of a sophisticated, state-of-the-art dive bomber, and the Arado, Heinkel and Junkers firms were asked to develop prototypes.

Given its complete lack of experience in combat aircraft, the new Hamburger Flugzeugbau had not been invited to participate in the Sturzbomber-Programm at all, but Vogt saw it as a golden opportunity to demonstrate the merits of his tubular-spar wing, which he felt was ideally suited to stand up to the stresses of dive bombing. Vogt therefore submitted his own design study, designated Project 6, to the C-Amt as a private venture.

Essentially, Vogt’s dive bomber was an aerodynamically improved and somewhat scaled-up version of the Kawasaki Ki.5. The wing used Vogt’s tubular spar, of which the center portion was made of welded chrome-molybdenum steel and the outer sections of riveted duralumin, sealed to contain 59.4 imperial gallons of fuel. Hydraulically operated trailing-edge flaps were installed in the center section and on the inboard portions of the outer wing panels. Each wheel was mounted between two vertical pneumatic shock absorbers and enclosed under streamlined fairings. The rectangular-section fuselage was a semimonocoque structure, with the pilot seated in an open cockpit over the wing’s trailing edge. Two fixed, synchronized 7.9mm MG17 machine guns were mounted in the upper decking of the forward fuselage. A similar weapon was installed in each undercarriage fairing, but there was enough space to accommodate 20mm MG FF cannons in place of the MG17s if the C-Amt’s specification called for greater firepower.

Project 6 was designed to use the Type XV engine that was then being developed by the Bayerische Motoren Werke. When the future of the BMW XV fell into doubt, the C-Amt asked Vogt to modify his design to take the BMW 132A-3, a license-built version of the 650-hp Pratt & Whitney Hornet 9-cylinder radial engine. Vogt obliged by resubmitting his design as Project 6a and added an alternative version, Project 6b, using a Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine. Hedging his bets even further, Vogt prepared a backup design, Project 7, using a biplane wing structure and a Wright Cyclone engine, but the C-Amt was sufficiently impressed with Project 6a to award the Hamburger Flugzeugbau a contract for three prototypes, under the designation Ha-137.

The first prototype, Ha-137V-1 (given the civil registration D-IXAX), was completed and flown at Hamburg in April 1935. It was quickly followed by a second prototype, the Ha-137V-2 (D-IGBI). Meanwhile, however, the State Ministry of Aviation (Reichsluftfahrtministerium, or RLM) had issued its definitive specification for the second-phase Sturzbomber in January 1935, stipulating that it have a rear gunner. Vogt had known that the two-seat requirement was coming, but a second crew position would have necessitated a somewhat larger aircraft than he had in mind, with an adverse effect on performance. He therefore continued work on the Ha-137 as a single-seater, gambling that it might still win over the RLM.

What Vogt did not know was that the deck had been stacked not only against his Ha-137 but also against the two official Sturzbomber-Programm contenders. Even though the specification was issued simultaneously to Arado, Heinkel and Junkers, it had, in fact, been drawn up around the design that the RLM had favored from the very beginning—the Junkers Ju-87.

Arado’s Ar-81V-3 biplane managed to produce an overall performance superior to that of the Ju-87V-2, but it was rejected by the RLM on principle as a retrogressive design. Heinkel designer Walter Günter produced the He-118, which was a larger but more powerful and aerodynamically refined monoplane than the Ju-87 and featured retractable landing gear. Chief of Aircraft Procurement and Supply Ernst Udet was sufficiently impressed to test-fly the He-118V-3 prototype himself on June 27, 1936. When Udet failed to adjust the propeller pitch as he went into a dive, however, the propeller “ran away” into excessively high rpm and ground up the reduction gears, on top of which the tail broke away. Udet bailed out safely, but the incident dashed the He-118’s last slim hope of breaking the Ju-87’s preordained hold on a production contract.

Ironically, the single-seat configuration that disqualified the Ha-137 from the Sturzbomber-Programm almost got it accepted in a different category. At the recommendation of Colonel Wolfram von Richthofen, the RLM agreed to sanction the continued development of the Ha-137, both as a backup for the Ju-87 and as a possible close-support aircraft, or Schlacht-flugzeug. Consequently, three more prototypes were ordered with the new Junkers Jumo 210 liquid-cooled engine. Whereas the radial-engine-powered first and second aircraft were regarded as prototypes for the Ha-137A, the third prototype, designated Ha-137V-3 (D-IZIQ), was completed with a supercharged 640-hp Rolls-Royce Kestrel 12-cylinder, liquid-cooled engine, as the prototype for a possible production model to be designated Ha-137B. While the earlier radial-engine models used a three-bladed, adjustable-pitch metal propeller, the Ha-137V-3 used a two-bladed fixed-pitch wooden propeller.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Testing of the first two prototypes began at Travemünde in the summer of 1935. In contrast to the disappointing Kawasaki Ki.5, the Ha-137 was praised for its good performance and pleasant handling characteristics, as well as its exceptionally sturdy structure. As with the Ki.5, however, the gull wings did nothing to improve visibility for the pilot during takeoff and landing.

The Ha-137V-1 was damaged in October when ammunition exploded in the starboard side of the wing center section during armament trials. The Ha-137V-3 participated in dive-bombing trials at the Rechlin test center in June 1936, but during that same month Ernst Udet replaced Richthofen as chief of the development section of the RLM’s Technischen Amt (which replaced the C-Amt). Although Udet was an ardent supporter of the dive bomber, he attached little importance to Schlachtflugzeug and promptly informed Vogt that no production contract would be awarded for the Ha-137. When World War II began on September 1, 1939, the close-support task was primarily relegated to the Ju-87’s obsolescent biplane predecessor, the Henschel Hs-123.

Meanwhile, Vogt’s design team learned that an aircraft carrier project was included in the 1936 budget, and work began on Project 11, a naval version of the Ha-137A, as well as a floatplane known as Project 11a. The Ha-137’s single-seat configuration and limited tactical radius, however, precluded any serious interest by the German navy.

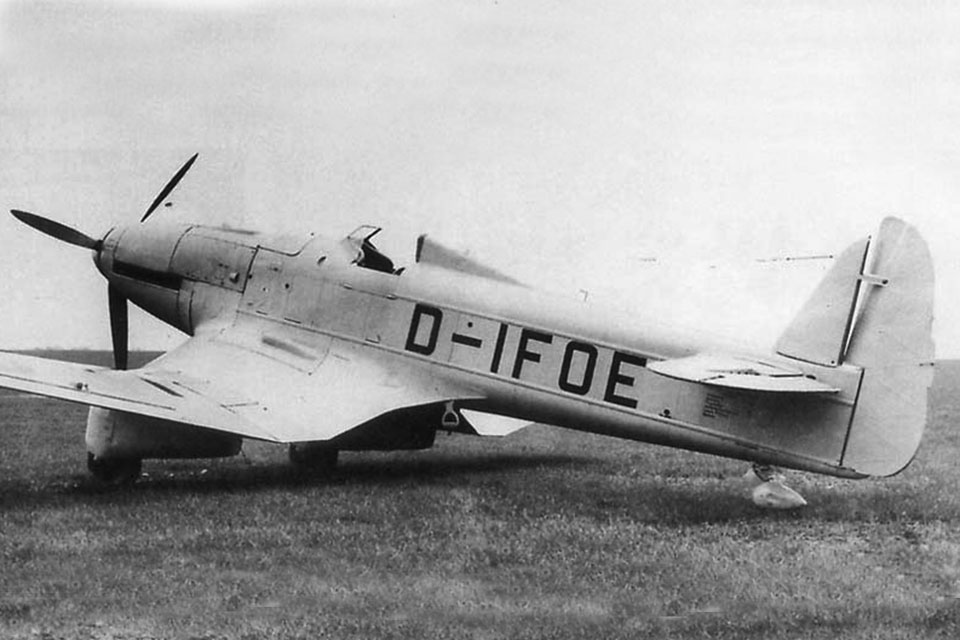

Despite the succession of setbacks its design had suffered, the Hamburger Flugzeugbau produced three additional Ha-137 prototypes, powered by 610-hp Junkers Jumo 210Aa engines and using three-bladed, adjustable-pitch metal propellers. Those were the Ha-137V-4 (D-IFOE), the V-5 (D-IUXU) and the V-6 (D-IDTE). The Ha-137V-4 had a wing-span of 36 feet 7 inches, a wing area of 252.952 square feet, a length of 31 feet 3⁄4 inch and a height of 9 feet 21⁄4 inches. Its maximum speed was 205 mph at 6,560 feet. Cruising speed was 180 mph, and range was 360 miles. The rate of climb without an external load was four minutes to 6,560 feet and nine minutes to 13,120 feet. The aircraft’s service ceiling was 22,965 feet. In addition to machine guns or cannons, the Ha-137V-4 was designed to carry four 110-pound SC50 bombs on under-wing racks.

The Ha-137V-6 was actually completed before the V-5, but it crashed in July 1937 and was destroyed. The Ha-137V-5 was delivered on October 26, 1937. The two surviving Jumo-engine prototypes subsequently served in various experimental trials. One of the prototypes performed some of the first firing tests with the Rheinmetall-Borsig 65mm Rauchzylinder RZ65 rocket missiles.

Although his Ha-137 seems to have been doomed from the start to one disappointment after another, the aviation world had not seen the last of Dr. Richard Vogt. In the summer of 1937, he unveiled the prototype of the Ha-138, a twin-boom flying boat that later entered service as the Bv-138 Fliegende Holzschuh (“Flying Clog”)—the only Blohm & Voss product to achieve any measure of mass production. Several of Vogt’s other designs, though less successful, would nevertheless gain him a niche in aviation history for sheer originality, ranging from the tiny Bv-40 glider fighter, to the giant Bv-238 flying boat (its maximum loaded weight, at 220,460 pounds, made it the heaviest aircraft in the world in 1945). In between were such bizarre concepts as the asymmetrical Bv-141 reconnaissance plane.

This article originally appeared in the July 1997 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe today, click here!