Severe weather rolled in across Nebraska Territory that June afternoon in 1860, the thunder masking the sound of a Sioux raiding party as it slipped in among the Pawnee ponies, killed the herdsmen and cut away about 30 of their enemy’s animals.

From their village on the Loup Fork of the Platte River, Pawnee warriors gave chase. When they caught up to the raiders, a fight ensued, but the Pawnees soon returned to their village bloodied and without their horses. A New York Times correspondent recorded a Pawnee’s description of the fight: “The wind blew strong—the rain fell fast—the Sioux arrows came amongst us like the rain, killing our men.”

Historically, the Pawnee people were split into four independent subtribes. The Skiri (Wolf Pawnees) were the first to migrate into what became Nebraska. The Chaui (Grand), Kithehaki (Republican) and Pitahaureat (Noisy), collectively referred to as the southern Pawnees, arrived after 1760 and hunted together south of the Platte. The Skiris remained apart from the others, hunting alone until the mid-19th century when dwindling Pawnee numbers (due to disease and warfare with the Sioux) prompted tribal leaders to end the ancient divisions.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

When farming, the Pawnees lived along the Platte in villages of dome-shaped earthen lodges. But after spring planting they drifted westward with the buffalo herds and lived in tepees. The Pawnees spent about eight months a year hunting on the Plains.

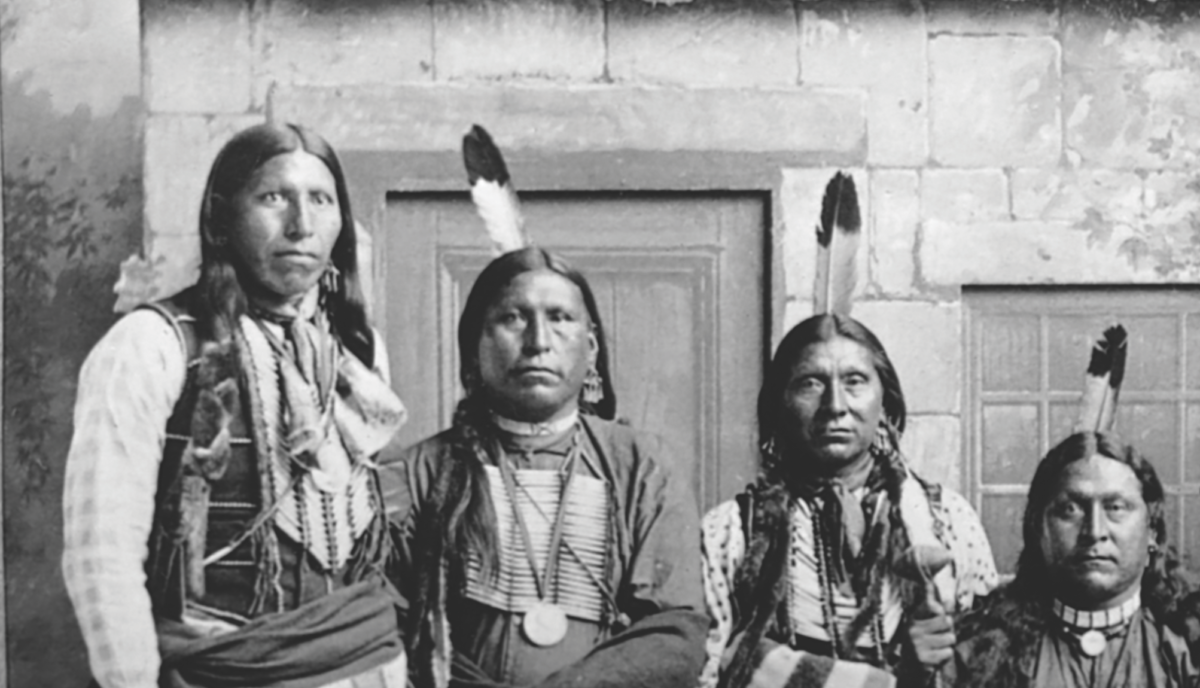

PAWNEE WARRIORS

In the 18th century Pawnee warriors raided the villages and herds of other tribes—leaving afoot and returning astride stolen horses. They met their first Anglo-Americans, including explorers Meriwether Lewis, William Clark and Zebulon Pike, during mostly cordial encounters in the early 19th century.

In September 1825 the Pawnees signed a treaty with the United States in which they agreed not to harass American traders traveling to Mexican-controlled Santa Fe. In return the government would “extend to them, from time to time, such benefits and acts of kindness as may be convenient and seem just and proper to the President.”

In the 1830s the government removed the Delaware, Shawnee and other Eastern tribes to Indian country west of the Missouri, and they in turn encroached onto Pawnee hunting grounds. The year 1832 was an especially bloody one for the Pawnees. In a fierce three-day battle with heavy casualties on both sides they defeated the Sioux near the junction of the Big Sandy and Little Blue rivers (in present-day Jefferson County, Neb.).

But the Comanches defeated the Skiris in a one-sided fight on the Arkansas River, and the Delawares burned the Grand Pawnee village on the Republican River. What’s more, smallpox decimated all four Pawnee subtribes, claiming some 3,000 lives. The next year U.S. commissioners persuaded the Pawnees to give up all land claims south of the Platte, thus allowing resettled tribes to hunt unmolested.

The fall of 1834 brought missionaries to the upper Platte, soon followed by a trading post that drew thousands of unfriendly Sioux. And while the Pawnees had beaten them soundly in 1832, the Sioux usually got the upper hand in subsequent confrontations, further weakening the Pawnee population.

CONFLICT INEVITABLE

The Pawnees were never at war with the United States, but conflicts were inevitable when the first wave of settlers encroached on Pawnee lands north of the Platte (without any payment to the tribe) in the wake of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.

After a particularly tough winter of 1855–1856 the impoverished Pawnees returned home that spring to find themselves largely displaced. A number of Pawnee men promptly signed on as scouts with Col. Edwin Vose Sumner’s punitive campaign against the Cheyennes.

Sumner gave them ponies and supplies when they mustered out, but a band of white frontiersman robbed them of everything. In the spring of 1857 a settler beat and then gunned down a young Chaui chief after the latter appeared at his door begging food. Tension mounted after that confrontation, as settlers feared retaliation from the “pestiferous banditti,” as one editor labeled the Pawnees. Newspapers called for their removal from settlement lands.

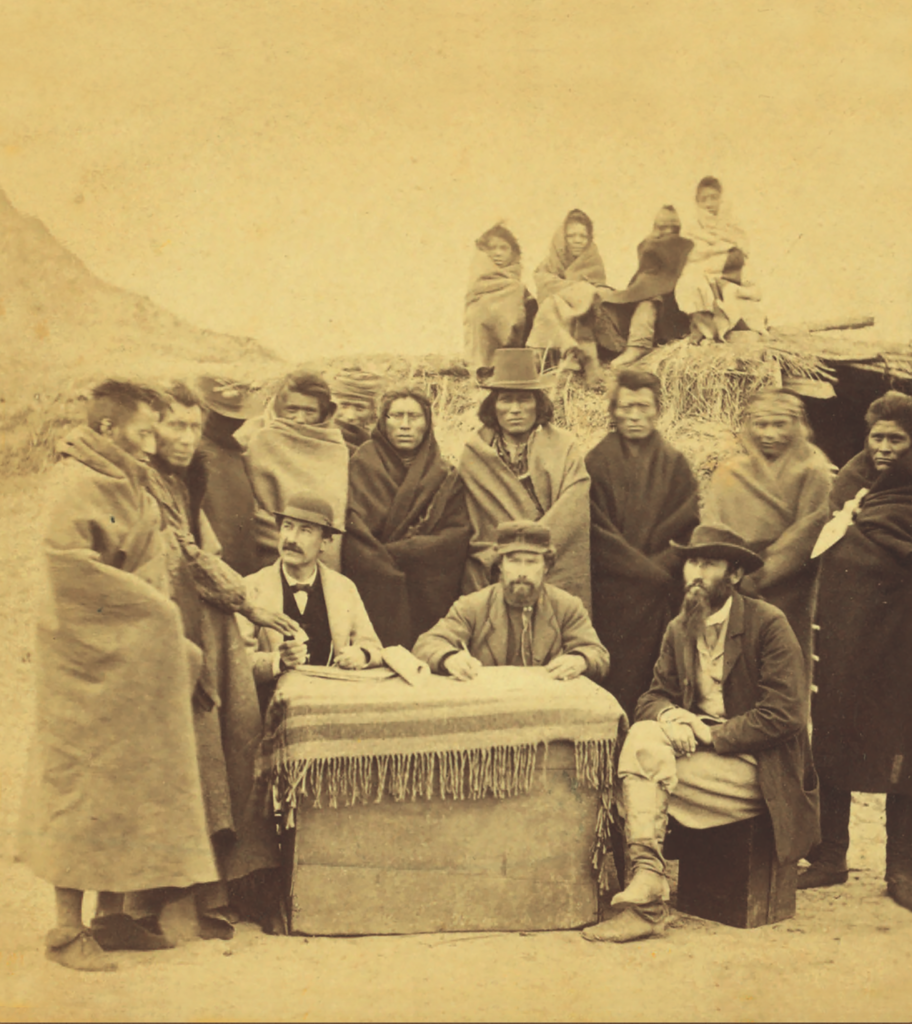

On Sept. 24, 1857, the Pawnees relinquished their lands in a treaty signed at Table Creek, Nebraska Territory. In return they received a small reservation (30 miles east to west and 15 miles north to south) on the Loup Fork and government aid amounting to $40,000 per year for five years and $30,000 per annum thereafter. But the rampaging Sioux remained a problem. In successive raids on the reservation between June and September 1860 the Sioux killed 13 Pawnees, burned 60 lodges and ran off more than 30 horses.

RAIDS ALONG THE OREGON TRAIL

In 1864 the Sioux and Cheyennes mounted deadly raids along the Oregon Trail across Nebraska Territory. That December Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis approached the Pawnee Agency, seeking scouts. While eager to fight hated foes, those who joined Curtis’ command saw no action and soon returned to the reservation. Soon after, though, Curtis authorized 1st Lt. Frank North to enlist more Pawnees for regular service. His new scouts performed so admirably, North was promoted to captain and then major.

The Pawnees called him Skiri Taka (“White Wolf”) and later the honorary title Pani Resaru (“Pawnee Chief”). The scouts guarded Union Pacific Railroad crews and also waylaid bands of Sioux, Cheyennes and Arapahos. North’s Pawnee Battalion delivered invaluable service during the 1865 Powder River Expedition and remained useful in the Indian wars through 1877.

In 1868–69, when the U.S. government removed the Sioux and Cheyennes from lands between the Platte and Arkansas rivers, the Pawnees likely presumed they could now hunt unmolested. But it was not to be. The railroad they were protecting was bringing in thousands of settlers, who were establishing homesteads in every part of Kansas and Nebraska. At the same time buffalo herds were declining.

The government continued to assist its American Indian allies but actually helped the Sioux more. For instance, in 1871 the Pawnees were receiving the $30,000 annuity allowed by the 1857 treaty, while the Sioux were provided $1,314,000 worth of beef.

On Aug. 5, 1873, a Sioux war party ambushed a Pawnee hunting party on the Republican, killing at least 70 men, women and children. Having had enough, the first group of Pawnees moved to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) that same year.

A second migration occurred in 1874, and a third group (mainly Skiris) went south in 1875, when the Pawnee Agency was relocated to Black Bear Creek, about 8 miles southwest of the Arkansas River. Today the Pawnee Nation is headquartered in Pawnee, with tribal jurisdiction over sections of Pawnee, Payne and Noble counties.

This article initially appeared in the February 2017 print edition of Wild West.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.