Many brave and wise Indian leaders appeared and gained respect and fame in the late 18th and early 19th century. Only a few of them, however, had the diplomatic skills and charisma to go beyond leading their own bands and their own tribes to form and lead intertribal alliances. Tecumseh the Shawnee, Red Cloud the Oglala Sioux and Sitting Bull the Hunkpapa Sioux all had the right stuff to become legends.

Born around 1768 somewhere near present-day Springfield, Ohio, Tecumseh developed an early hatred for the white man’s steady encroachment into Indian homelands. When he was 6 years old, after invading Virginia frontiersmen killed his father, his mother took him to the spot and cried out to him: ‘Avenge! Avenge!’ At age 12, too young to be a warrior, Tecumseh watched George Rogers Clark and some 1,000 men defeat his people and burn his town. Filled with bitterness, he swore vengeance on the Long Knives.

By the early 1790s, white Americans were traveling down the Ohio River, turning north and settling on Shawnee hunting grounds. Tecumseh led raiding parties on white settlements and helped defeat two armies sent out to subdue the Indians. Officials in George Washington’s administration feared a great and powerful alliance of the tribes, and the president sent Maj. Gen. Anthony Wayne out to ‘tame’ the Indians. At the Battle of Fallen Timbers, Tecumseh was the greatest rallying force for the Indians, many times stopping retreats and inspiring them to stand and fight, but he could not prevent a crushing defeat.

Nor could he prevent chiefs of other tribes from signing the Treaty of Greenville, thus ceding all of what is now the state of Ohio and part of Indiana to the whites. After that there was a period of relative peace between 1795 and 1809. But during those years, William Henry Harrison, a military man who became governor of Indiana Territory, used liquor, oratory and ceremonial pomp to persuade various chiefs to surrender 50 million acres.

By 1805, Tecumseh was traveling between the Appalachians and the Mississippi persuading other tribes to join his confederacy. He told Harrison: ‘The Indians were once a happy race, but now are made miserable by the white people, who are never contented, but always encroaching. They have driven us from the great salt water, forced us over the mountains and would shortly push us into the lakes. But we are determined to go no farther.’ His oratory, of course, did not stop the white invasion, and Tecumseh decided to make use of the religious fervor being spread by his younger brother Tenskwatawa, called ‘the Shawnee Prophet.’ He planned to reform bad Indian habits, to abandon everything the white man had brought into the Indians’ lives, and to try to form a huge confederacy that would include every tribe in U.S. territory.

Within three years the brothers had built Prophetsville, a very large town where the Tippecanoe River flows into the Wabash, and had persuaded many chiefs that this was the last chance to stop the white encroachment. But in 1809, some Ohio Valley chiefs signed the Treaty of Fort Wayne, ceding many square miles of land. Tecumseh decided it was time for action and told Harrison he must give back the land. The governor, of course, refused. Tecumseh thought the confederacy was not quite ready for military action and withdrew. He went south to get the final agreement from a number of tribes to join the alliance. British Indian agents were encouraging an Indian uprising against the Americans.

In 1811, Harrison decided to take action while Tecumseh was away, visiting the southern tribes Tecumseh had instructed Tenskwatawa not to fight Harrison, but the strong-arm governor provoked a battle at Prophetstown by moving troops to within 600 yards of the town. Insulted, the young warriors fought on November 7, 1811. Harrison’s troops won the Battle of Tippecanoe, and the next day they burned the great town, center of the confederacy. The Americans had destroyed the great alliance.

Tecumseh rallied many Indians to the British cause and helped capture Detroit during the War of 1812, but he fell on October 5, 1813, at the Battle of the Thames (near present-day Thamesville, Ontario, Canada), while shouting encouragement to his warriors. The leading proponent of Indian unity was gone, and there was no one to replace him to oppose white settlement east of the Mississippi River.

Half a century passed, and whites began to appear in droves west of the Mississippi. Red Cloud, was born about a decade after Tecumseh’s death, and his Oglala Sioux followers were willing to talk with the whites. There could be peace if the white man stayed out of Sioux hunting grounds and stopped using the Bozeman Trail.

The government called a council for the spring of 1866 at Fort Laramie, on the Platte River not far from the Wyoming-Nebraska border. Negotiations seemed to be going well until Red Cloud and his chiefs found out that Colonel Henry B. Carrington had arrived with 700 soldiers to build forts on the Bozeman Trail. The Federal peace commission learned that there could be no peace unless a treaty had the support of Red Cloud, who was respected not only by the Oglalas but also by the Bruls and other Sioux and by their Cheyenne allies. ‘The Great Father sends us presents and wants us to sell him the road, but the white chief goes with soldiers to steal the road before Indians say Yes or No,’ said Red Cloud. He then stormed out of the Laramie meeting.

A real war began, with Red Cloud the head soldier. Red Cloud was the only Plains Indian who could gather so many confederates and keep them together long enough to wage a successful campaign against the white man’s incursions. He gathered 250 lodges of Sioux and Cheyennes in the cause, which provided him with about 500 warriors, and carried on continuous guerrilla warfare along the length of the Bozeman Trail. Seventy white people were killed, 20 wounded, and 700 horses, mules and cattle were taken. The soldiers stuck close to their forts.

The Great White Father had to do something, so in 1868 he sent out a peace commission. Whites, according to the Fort Laramie Treaty, were to be banned from Sioux hunting grounds, and their forts were to be abandoned. After the soldiers left, the Indians had the satisfaction of burning the hated forts. The so-called Red Cloud War had been a victory for the Indians. There was relative peace until gold was discovered in the Black Hills in the mid-1870s and the government failed to keep out the white prospectors. Red Cloud, who had come to recognize the hopelessness of challenging the overwhelming numbers of the white man, did not ‘go shooting,’ and that angered many of his people. Although he came to believe in compromise rather than war, Red Cloud never stopped fighting to protect the Sioux culture. Unlike Tecumseh, he did not go out in a blaze of glory. Red Cloud lived until 1909. But like Tecumseh, he had effectively resisted the white invasion…for a while.

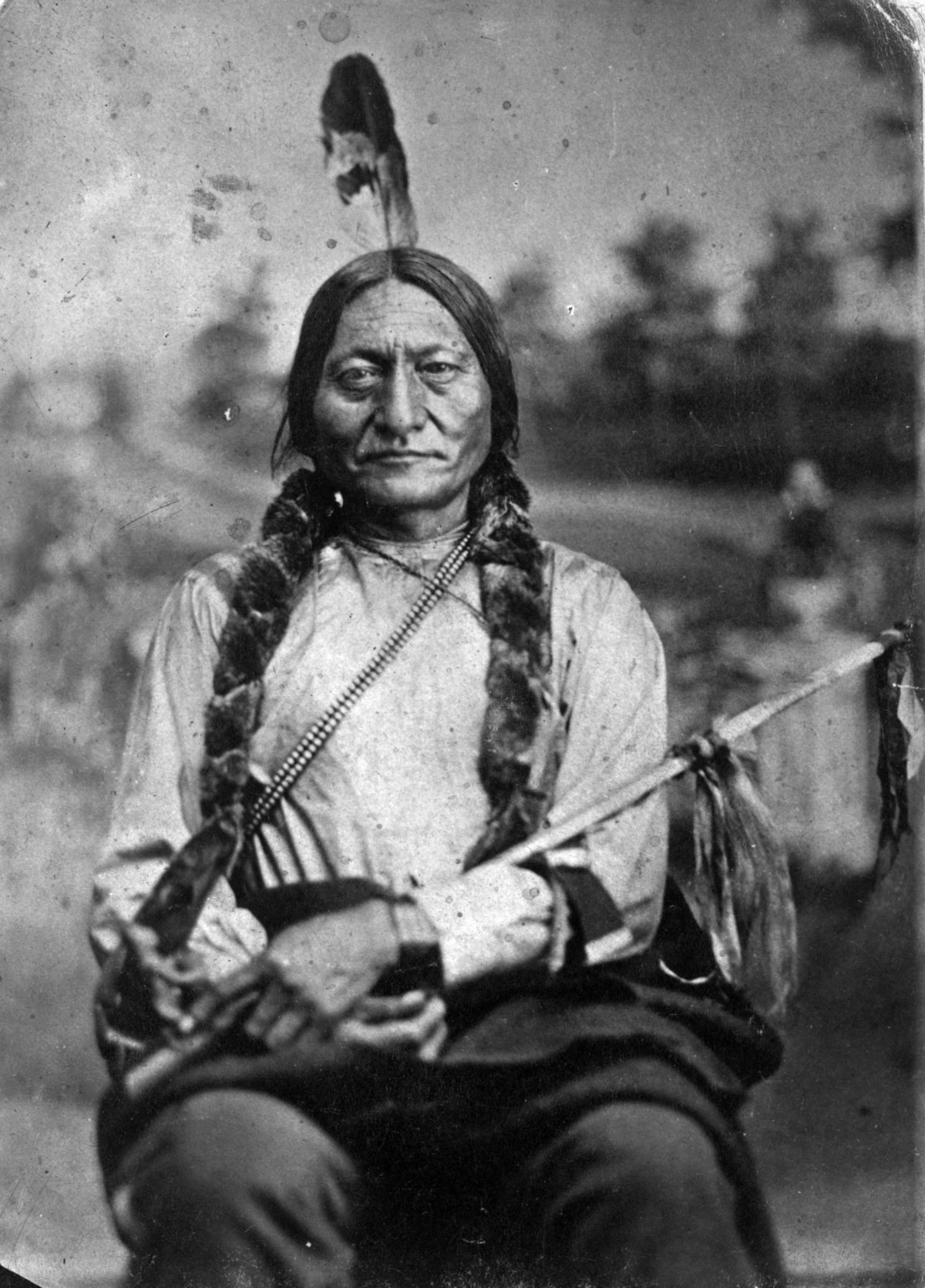

The Hunkpapa leader and holy man Sitting Bull replaced Red Cloud as the chief symbol of resistance on the northern Plains. Born in March 1831 near the Grand River (in today’s South Dakota), Sitting Bull tried to avoid whites until the situation became intolerable. Then he called for action, and many Sioux, Cheyennes and Arapahos were happy to follow his lead.

In 1868 many divisions of the Sioux rejected Red Cloud’s peace with the United States and did something they had never done before — choosing one man to be the leader of all the Teton Sioux. His name was Sitting Bull. Crazy Horse, a leading warrior, was essentially second in command. The Fort Laramie Treaty, however, largely kept an uneasy peace until all Indians were ordered to go to reservations by January 31, 1876, or be deemed ‘hostiles.’

That March, one of the columns of Brig. Gen. George Crook attacked a Cheyenne village not even on the list of hostiles. The survivors made their way to Sitting Bull up in Powder River country, and he gave them food and shelter. He decided the time for patience was gone. Sitting Bull sent messages to all Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho bands. He wanted them to join him.

In the spring of 1876, he sent out small raiding parties to steal good horses, guns and ammunition, while the U.S. Army mounted a campaign to subdue all Plains Indians who were off their reservation. In June, Sitting Bull danced the Sun Dance until he fell unconscious and had a vision of soldiers falling like rain. Not only did he believe in his vision, but so, too, did most of the warriors around him. The Indians would fight the soldiers and be victorious!

On June 17, Crazy Horse fought Crook to a standstill at the Rosebud. Sitting Bull’s vision had not yet come true, but one of the leading white fighting men had been knocked out of the picture. Sitting Bull moved his great allied camp to find more plentiful food for his people and horses. (see ‘Sitting Bull’s Movable Village’ in the December 2000 Wild West). He eventually chose a place along the Little Bighorn River where the grass was good and there was game nearby. That is where Lt. Col. George Custer and the 7th Cavalry found them.

Although Sitting Bull and his allies won a great battle, on June 25–26 at the Little Bighorn, they could not win the war. Most of the Indians, hungry and desperate, returned to the reservations the next year. Sitting Bull instead went to Canada, where he found peace for a while. On July 19, 1881, he, along with 187 followers, turned himself in at Fort Buford, Dakota Territory.

Sitting Bull mostly stayed at the Standing Rock Agency beginning in 1883 and continued to have much influence. When the Ghost Dance movement stirred up the Sioux in 1890, he became — at least in some eyes — a feared figure once more. On December 15, 1890, Sitting Bull died in a fight near his cabin on the Grand River when Indian police attempted to arrest him.

Of Tecumseh, Red Cloud and Sitting Bull, which one was the greatest? Tecumseh’s widespread and powerful alliance was betrayed by his brother. Sitting Bull put together the most complete and famous single Indian victory. Red Cloud, however, actually defeated the U.S. Army over a long campaign and temporarily shamed it. The nod probably must go to Red Cloud.

This article was written by J. Jay Myers and originally appeared in the October 2001 issue of Wild West.