Gripped by the fear of an insidious plague stalking its streets, no one, rich or poor, was safe in the nation’s capital and largest city in the summer of 1793. Forty percent of its residents, among them President George Washington and many of the young republic’s founders, would flee the gruesome killer that would end the lives of 10 percent of the city’s population in just four months. Fueling the pervasive dread that shrouded Philadelphia’s 50,000 residents was the mysterious manner in which the disease known as yellow fever was transmitted.

An unusually wet spring followed by a hot summer fostered the proliferation of millions of mosquitoes that carried the devastating virus in the nation’s premier port city. Yellow fever’s grim and relentless march was in full force by early August. Only the cool weather of November would finally bring the epidemic to a halt.

In addition to Washington and his wife, Martha, Vice President John Adams, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton and Representative James Madison’s future wife, Dolley Payne Todd, all lived in Philadelphia when the epidemic broke out, and it had a profound impact on each of their lives. Their experiences provide us with a window into 18th-century American medicine and disease, and the complex ways in which illness affected everyone from the poor to the elite. Despite the founders’ privileged status, which allowed them access to the best medical knowledge and trained physicians, those advantages did not necessarily provide protection from serious sickness.

Yellow fever is a fearsome disease, characterized in severe cases by high fever, chills, purplish bruises, jaundice and vomiting of black, blood-filled bile lasting a week to 10 days. Then, as now, there was no cure, but those who possessed a “strong constitution” and received good supportive care often recovered by letting nature take its course. Despite the disease’s horrific symptoms, modern data suggest that fatality rates varied greatly, ranging from 10 to 60 percent. People with compromised immune systems or underlying illness and those who lived in crowded conditions with poor sanitation and inadequate diets were most vulnerable. The virus arrived with an initial pool of infected humans, likely travelers on incoming ships from tropical foreign ports, but it was carried and spread through the sting of infected female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, a fact that no one at the time understood. The insects bred in freshwater containers, including cisterns and puddles of rainwater in crowded urban centers, particularly in warm regions.

One of the Philadelphia epidemic’s earliest victims appears to have been Mary (Polly) Lear, the wife of President Washington’s personal secretary, Tobias Lear. Mrs. Lear, who was only in her mid 20s, lived with her husband in the president’s mansion on High Street. Martha Washington looked upon Polly as a surrogate daughter, since by 1793 all four of her children from her first marriage were dead. (Two had died in childhood, one as a teenager and one as a young adult.) Martha wrote to her niece of Polly’s demise: “We have had a melloncholy time for about a fortnight past Mrs. Lear was taken with a fever—a doctor was called in but to no purpose [and] her illness increased till the eighth day she was taken from us. . . . She is generally lamented by all that knew her…and always [previously] in good health.” Because of his close relationship with the Lears, Washington made an exception to his policy of not attending local funerals.

The wife and child of Thomas Jefferson’s coachman, Thomas Lapseley, whom Jefferson considered part of his extended “family,” also succumbed to the disease. Lapseley served as Jefferson’s driver from May to September 1793. John Adams, who had a tendency to hypochondria, fled Philadelphia early in the course of the epidemic to join his wife, Abigail, in Quincy, Mass., but they both experienced great anxiety about the fate of their son Thomas, a law student in Philadelphia. Washington, Jefferson and Adams had probably developed immunity to the disease through previous exposure to it. Not everyone was so fortunate.

Dolley Payne Todd was the wife of rising young lawyer John Todd Jr. The Todds lived in a comfortable three-story red brick home at Walnut and Fourth streets, with John’s law office on the first floor. When the epidemic spread, John sent Dolley, their 2-year-old son, John Payne Todd, and newborn, William Temple Todd, to a farm at Gray’s Ferry, an area in the countryside considered safer than the city. But John remained in town to care for his parents, who had contracted the disease, and conduct his law practice. He visited his wife and children when he could, but his parents were slipping away. Dolley poured out her anguish in a letter to her brother-in-law in nearby Darby: “A reveared Father in the Jaws of Death, & a Love’d Husband in perpetual danger. . . . I am almost destracted with distress & apprihension—is it two late for their removal? . . . I wish much to see you, but my Child is sick & I have no way of getting to you.”

By this time, John Todd was also sick, but after burying his parents, he rode out to see his wife and sons. He died that same day along with baby William, leaving 26-year-old Dolley and toddler John Payne alone to cope with their own bouts of the disease. They survived, and as John Harvey Powell noted in his classic study of the outbreak Bring Out Your Dead, Dolley’s “role in history began in the yellow fever [epidemic] of 1793.” An attractive widow, Dolley would marry future president James Madison less than a year after Todd’s death, but understandably her tragic experience left her always anxious about the health of family members.

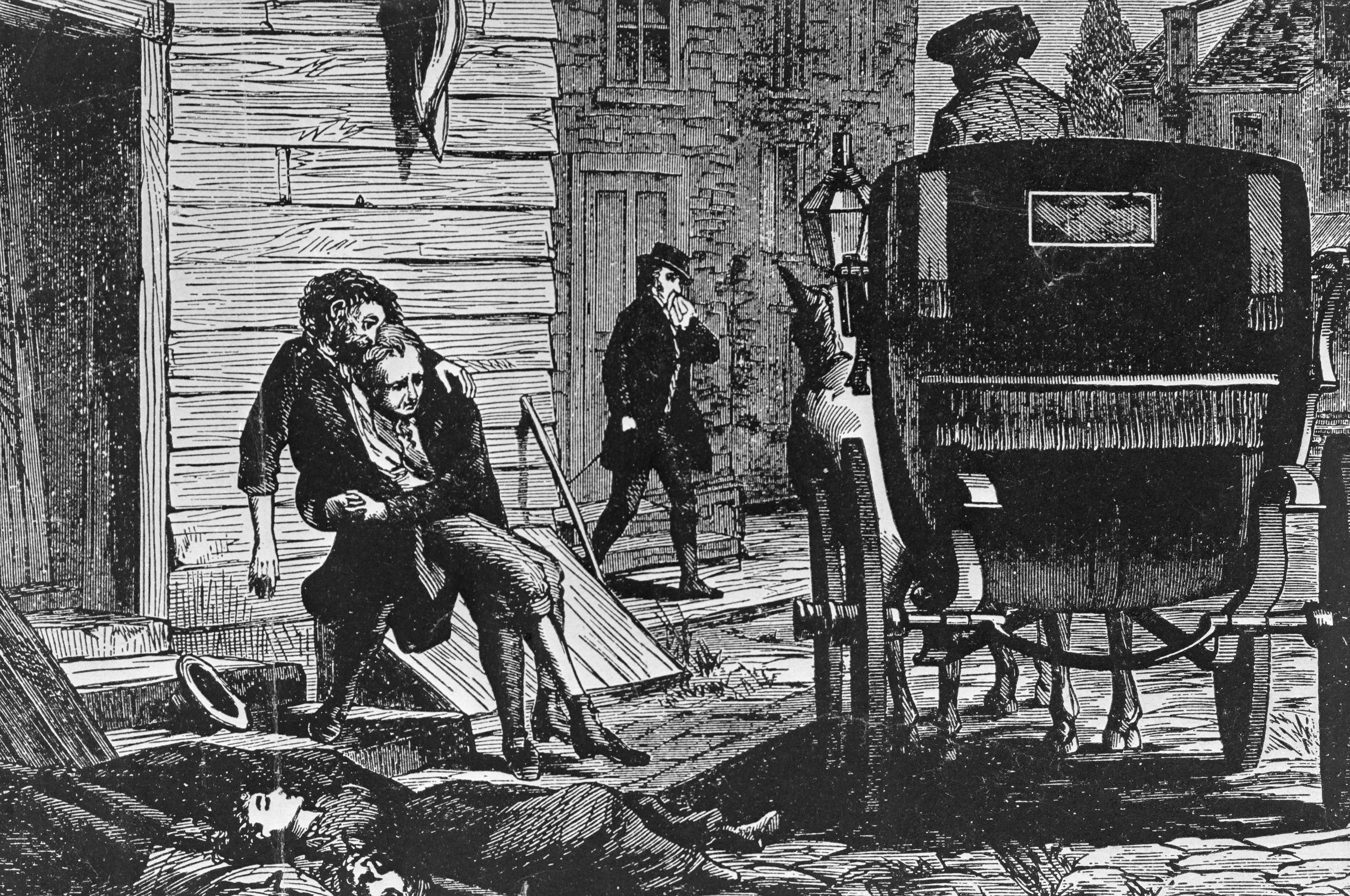

Those who had the means to flee Philadelphia did so in the summer and fall of 1793, leaving the poor and infirm behind with the limited assistance of a core group of selfless city officials, physicians and private citizens. Mayor Matthew Clarkson faithfully went to his office daily, and he and his largely volunteer committee organized Philadelphia’s response to the epidemic. They supervised the temporary hospital at Bush Hill (once the vice presidential residence, which had been vacated by Adams in 1792), visited the sick and provided them with food, and made arrangements to transport fever victims to the hospital and those who died to Potter’s Field for burial. The compassionate devotion of Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, to his yellow fever patients, even after he himself became ill, was exemplary, but his adherence to the “heroic” medical practices of radical purging and excessive bloodletting undoubtedly hastened many of his patients to their deaths.

Social, economic and political life in Philadelphia ground to a standstill. President Washington encouraged government workers to leave the city for Germantown, about six miles away, which was not affected by the fever. Albeit reluctantly, Washington and the first lady also escaped at the height of the epidemic. Washington customarily left Philadelphia for Mount Vernon in the fall, but this time he seemed conflicted, informing Tobias Lear, “It was my wish to have continued there longer, but as Mrs. Washington was unwilling to leave me surrounded by the malignant fever wch. prevailed, I could not think of hazarding her and the Children [Martha’s grandchildren] any longer by my continuance in the City the house in which we lived being, in a manner, blockaded by the disorder…becoming every day more and more fatal.”

Thomas Jefferson’s government duties kept him in Philadelphia through early fall, but the secretary of state, whose passion was science, particularly the study of health, disease and medicine, carefully documented the details of the epidemic as it unfolded. He accurately described the symptoms of yellow fever as beginning “with a pain in the head, sickness in the stomach, with a slight rigor, fever, black vomiting and feces, and death from the 2nd to the 8th day.” During the crisis he corresponded with several political colleagues, including his close friend Virginia congressman James Madison, whom he kept updated on the numbers of people afflicted with the disease and those fleeing the city in the hope of outrunning the plague.

In early September 1793 Jefferson reported, “A malignant fever has been generated in the filth of Water street which gives great alarm. About 70 people had died of it two days ago, and as many more were ill of it. It has now got in to most parts of the city and is considered infectious. . . . Every body, who can, is flying from the city, and the panic of the country people is likely to add famine to the disease.” A week later he observed, “The yellow fever increases…and it is the opinion of the physicians there is no way of stopping it…no two agree in any one part of their process of cure.”

Jefferson’s pithy summing up of the situation reveals the helplessness of contemporary medicine to deal with the outbreak as well as Jefferson’s frequently displayed skepticism about the skills of doctors. His words also reflect the debate regarding the cause of the epidemic, which was attributed variously to the arrival of French immigrants from Haiti, vague “malignant” miasmas emanating from the ground and even exhalations from spoiled coffee grounds on the wharves of the city’s waterfront district. Philadelphia’s bustling port was crucial to the city’s economic success, and vessels filled with goods and passengers arrived and departed daily. The yellow fever debate was often aligned along political factions, with opinion sharply divided by Federalist and Republican affiliation. Led by Hamilton, most Federalists insisted that the yellow fever was “imported” and had arrived in Philadelphia from the West Indies through French citizens fleeing the French Revolution via Haiti (then Saint-Domingue). Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans pointed to local domestic conditions as its cause.

In September many offices and most banks shut down, and Jefferson was left with only one clerk, which impeded his ability to carry on business. “An infection and mortal fever is broke out in this place,” Jefferson reported. “The deaths under it, the week before last, were about forty; the last week fifty. This week they will probably be about two hundred, and it is increasing. Every one is getting out of the city who can. The President…set out for Mount Vernon. . . . I shall go in a few days to Virginia. When we shall reassemble again may, perhaps, depend on the course of this malady.” The situation deteriorated rapidly, for the next day Jefferson wrote Madison, “The fever spreads faster. . . . It is in every square of the city. All flying who can.” Jefferson, accompanied by his younger daughter, Maria, finally left in mid-September for Monticello.

Meanwhile, Alexander Hamilton, Washington’s right-hand man, informed the president that he feared he was “in the first stages of the prevailing fever.” Washington expressed his concern but believed the “malignancy of the disorder is so much abated, as with proper & timely applications not much is to be dreaded.” He sent Hamilton and his wife, Elizabeth, a gift of six bottles of fine wine, and Martha cautioned Elizabeth in a letter to “take care of yourself as you know it is necessary for your family,” then added, “The President joins me in devoutly wishing Colo[.] Hamilton’s recovery.”

Jefferson’s reaction to Hamilton’s illness was not as generous. The two were bitter political enemies, and Jefferson, leader of the Republican faction, used the situation to attack Federalist Hamilton as a coward for exaggerating the degree of his illness, which Jefferson at first believed to be only a typical “autumnal fever.” However, Jefferson later admitted to Madison, “H. had truly the fever, is on the recovery, and pronounced out of danger.”

Hamilton received many letters from friends who wished “to join with All ranks in the general Joy diffused upon hearing of your safe recovery from the present Malignant complaint which prevails in Philadelphia and hath proved fatal to so many of its inhabitants.” Hamilton attributed his return to health primarily to the services of Dr. Edward Stevens, a rival of the Republican Dr. Rush. He publicly praised Stevens’ “natural treatments,” which emphasized cold-water baths and dosing with bark (quinine) and wine. More likely, the Hamiltons recovered because they had only mild cases of the disease and were otherwise in good health. Hamilton’s assertion that Stevens’ “mode of treating the disorder varies essentially from that which has been generally practiced” was a pointedly negative reference to Rush’s aggressive treatment of yellow fever.

Washington’s strong sense of political responsibility compelled him to return to the Philadelphia area before the epidemic had run its course. He left Mount Vernon at the end of October, met up with Jefferson in Baltimore and the two settled in Germantown to await the end of the epidemic and the subsequent return of Congress. In early November, Washington ignored the threat of contagion and left for Philadelphia. His public inspection of the streets on horseback helped restore the city’s confidence. Deciding the health crisis was resolving, Washington continued with plans for December congressional meetings. Members gradually returned over the next few weeks, although fear of yellow fever still hovered over Philadelphia’s inhabitants.

After a hard frost and the arrival of cold weather in November, Jefferson was able to report to his older daughter, Martha Randolph, that “the fever in Philadelphia has almost entirely disappeared.” Jefferson also informed Madison, “The Physicians say they have no new subjects since the rains. Some old ones are still to recover or die, and it is presumed that will close the tragedy. The inhabitants, refugees, are now flocking back generally.” No one seems to have made the connection between the end of mosquito season and the cessation of the epidemic.

That same month, Thomas Adams, who had fled Philadelphia for Woodbury, N.J., during the worst of the epidemic, assured his parents that he had heard “from the Best authority” that if proper precautions were taken by airing out homes and whitewashing walls (lime was regarded as a disinfectant), it would be safe to return to Philadelphia. He arrived there on November 19 and wrote his mother, “The idea of danger is dissipated in a moment when we perceive thousands walking in perfect security about their customary business, & no ill consequences ensuing from it.” He noted, however, “Many of the inhabitants are in mourning, which still reminds us of the occasion, but a short time will render it familiar.”

John Adams returned to the devastated city on November 30 and wrote Abigail that “Finding by all Accounts that the Pestilence was no more to be heard of…The principal Families have returned, the President is here, Several Members of Congress are arrived and Business is going on with some Spirit.” A few days later Adams observed with relief, “The Night before last We had a deep Snow, which will probably extinguish all remaining Apprehensions of Infection. We hear of no Sickness and all Seem at their Ease and without fear.” But Martha Washington, in a January 1794 letter to a niece, poignantly described the toll the disease took on Philadelphia’s citizens: “They have suffered so much that it can not be got over soon by those that was in the city—almost every family has lost some of their friends—and black seems to be general dress in the city.”

Epidemics provided the impetus for several early American healthcare initiatives. As early as 1777, during the Revolutionary War, Adams noted with satisfaction that the Continental Congress had passed legislation that expanded the army’s Hospital Department. He wrote approvingly to Abigail, “The expense will be great, but humanity overcame avarice.” Following another serious yellow fever outbreak during his presidency, Adams signed the Seaman’s Act of 1798, creating the Marine Hospital Service “to provide for the relief and maintenance of disabled seamen,” who were often exposed to contagious fevers and other public health threats in the course of their duties. The magnitude of the 1793 death toll in Philadelphia left a deep impression on Jefferson, and it probably influenced his 1801 decision to use his presidential power to fight another major disease, smallpox, through the support and dissemination of a safer, more effective vaccine developed by Edward Jenner. As he wrote to a physician in 1802, “I think it important…to bring the practice of the [smallpox] inoculation to the level of common capacities; for to give to this discovery the whole of value, we should enable the great mass of the people to practice it on their own families & without an expense, which they cannot meet.” In 1813 President Madison went one step further when he signed into law a statute to encourage wider smallpox vaccination, one of the nation’s earliest public health bills. The legislation was aimed at regulating the Jenner vaccine to protect Americans from unscrupulous purveyors who offered adulterated versions. The Vaccine Act of 1813 was the first federal law to oversee drug purity with an eye toward consumer protection.

The founders’ personal experiences led them to realize early on that government had compelling reasons to shoulder some new responsibilities with respect to the health and well-being of its citizenry. They saw first-hand that epidemics not only brought personal devastation, they also played havoc with commerce and political life. Washington, Jefferson, Adams and Madison clearly recognized that the social, economic and political health of the nation was inextricably tied up with the physical health of its people.