Forget the myths and give the first president his due

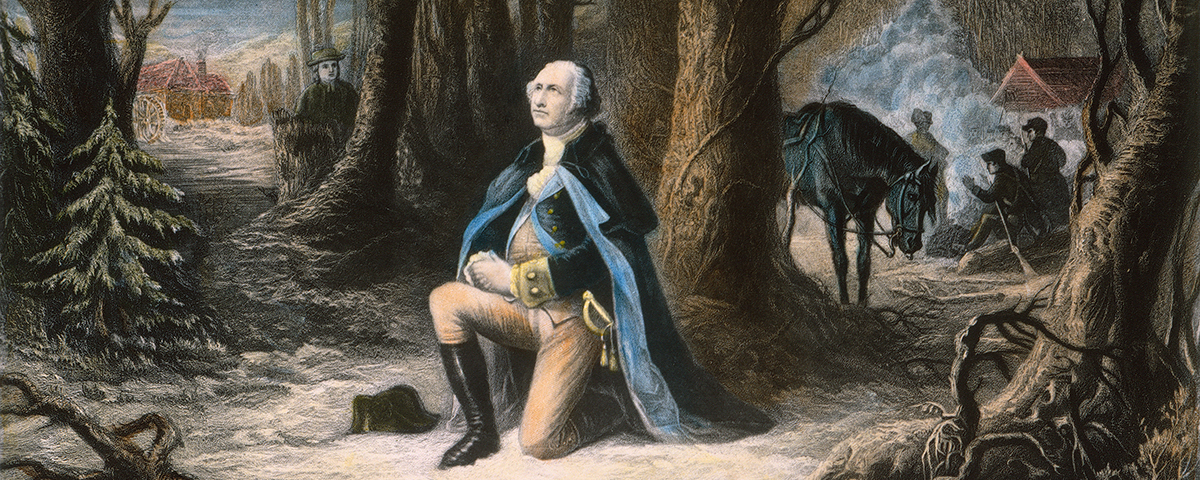

Myths encrust George Washington like barnacles on a boat hull, and historian John Rhodehamel crisply explains why it is time to scrape them away. “The most successful statesman in American history is often best remembered as a boy with a hatchet or as a simpleminded prig kneeling in the snow to pray,” the former Mount Vernon archivist writes in his 2017 book, George Washington: The Wonder of the Age. “A tawdry mythological excrescence oozing Victorian pieties and wooden teeth has gained a greater hold on our national imagination than the epic of Washington’s indispensable leadership in the making of the great nation that probably would not have come to be without him.”

The two most iconic images of Washington are of boy George hacking down his father’s precious cherry tree and of him praying on his knees in the snow at Valley Forge. Both come from the pen of Parson Mason Locke Weems, author of The Life of Washington, a work first published in 1800 that has gone through more editions

than any other book on the great man, profoundly influencing multiple generations’ views of Washington, even though Weems was much more preacher than historian.

Intent on making Washington a model for American youngsters, Weems emphasized truisms over truth. For example, he has George’s half-brother Lawrence weeping with joy to learn of George’s valor in the French and Indian War. Lawrence died in 1752, two years before that war began. Weems portrays a dying Washington in 1799 wanting to commune with his God and so asking all present to leave the room—then tells readers what Washington said to the Almighty.

Cherry, Cherry

The cherry tree incident, which debuted in the Weems book’s sixth edition, has young George coming clean over a bad move. “I can’t tell a lie, Pa; you know I can’t tell a lie,” he tells his father. “I did cut it with my hatchet.” An ecstatic Augustine Washington cries, “Run to my arms, you dearest boy! Glad am I, George, that you killed my tree; for you have paid me for it a thousand fold.”

Not only implausible but un-disprovable, the curious case of the chopped cherry tree has flourished without a scintilla of evidence, though adherents like historian Peter Lillback say there is proof. “The story must have had some circulation,” Lillback writes in his 2006 book Sacred Fire. “The evidence for this is a vase made in Germany around the time of the American Revolution (between the 1770s and 1790) honoring its leader, by depicting George as a young boy with a hatchet and bearing the initials, ‘GW.’”

So seemingly solid an assertion demands examination, which I undertook. A richly detailed color photo of the tankard appears in Pictures of Early New York on Dark Blue Staffordshire Pottery by R. T. Halsey. The photo shows not a cherry tree, but a barren trunk with limbs. The male figure is a man, not a boy. And the initials on

the mug are not “GW” but “CW.” In short, this container has absolutely nothing to do with George Washington.

Valley to Pray

“The most sublime picture in American history is of George Washington on his knees in the snow at Valley Forge,” President Ronald Reagan declared of a legend incorporated into the 17th edition of the Weems panegyric. Many Americans regard skepticism about this tale as tantamount to treason, if not heresy. The Continental Army’s trial by adversity in 1777-78 rendered Valley Forge “a place enshrined in mythology ever since as a kind of American Gethsemane, where Washington, the American Christ, kneels in prayer amidst bloodstained snow beseeching the Lord for deliverance,” writes historian Joseph Ellis.

However sublime the imagined scene might be, whatever symbolic truth the image conveys, logic and context dictate that it did not happen. It is true that George Washington held that God, while inscrutable, did intervene in human history, and Washington did believe in prayer. Thus, there is nothing implausible about Washington, as his soldiers were suffering at Valley Forge during that brutal winter, seeking divine help. Even so, “Praying Washington” has no basis in fact and does not comport with what we know about the commander-in-chief and his personal religious practices. Samuel Eliot Morison notes that the ostensible scene “is so little in accord with Washington’s character, habits & gentlemanly reticence as to be considered untrue per se.” It was not in Washington to make a display of religiosity. Contemporary observers reported that Washington did not pray on his knees and no known contemporary statements have him doing so. Invoking Washington’s fastidiousness, Rhodehamel jibed that kneeling in snow would have soiled his uniform, an abhorrence to the commander-in-chief.

And a practical query intrudes: If General Washington was leaving camp to pray in solitude, why pray so loudly as to be audible from a distance?

No contemporary evidence validates the tale. When, in 1918, believers lobbied the Valley Forge Park Commission to memorialize the spot where Washington knelt, investigators scoured the Library of Congress and other Revolutionary War sources. “In none of these were found a single paragraph that will substantiate the tradition of the ‘Prayer at Valley Forge,’” the commission said.

And then there are the facts that can be known, such as the identity of the supposed onlooker. Weems describes Isaac Potts, a Quaker patriot and owner of the farmhouse Washington was using as a temporary headquarters, reporting how he watched in awe as Washington, done with his devotions, returned to the residence/command post with “a countenance of angelic serenity.” The sight, according to Weems, prompted Potts to call out to his wife, “Sarah, my dear Sarah! All’s well!”

There actually was an Isaac Potts, and that Isaac Potts actually did have a wife named Sarah—but not until 1803. In 1777, Potts was married to a woman named Martha. More significantly, at the time that the beatific scene supposedly occurred, Isaac Potts was not at Valley Forge, according to Bryn Mawr College archivist Lorett Treese in the 1995 book Valley Forge: Making and Remaking a National Symbol. Between 1774 and 1782, Potts was living in Pottsgrove, Pennsylvania. He had rented his Valley Forge dwelling to a relative, Deborah Hawes, who sublet the place to the Continental Army, as confirmed by rent receipts that were made out to her, not to Isaac Potts.

Smiling George

Some folks say George Washington was a humorless cold fish. A much-repeated story has Washington intimate Gouverneur Morris betting Alexander Hamilton that he can behave as familiarly with Washington as with any friend. In the company of others, Morris claps Washington on the shoulder and says, “My dear General, how happy I am to see you look so well!” only to draw an icy silence as Washington removes Morris’s mitt and stares him down until Morris retreats in chagrin.

The story does reflect a valid point. George Washington did carry himself with a gravitas that could convey reserve, even aloofness. But no contemporaneous sources lend this anecdote credence, and the details of time and place defy reconstruction. As historian Garry Wills notes, this story first appeared as third-hand gossip in a book printed 80 years after the purported event.

The harm in this assertion lies in its wrongheaded portrayal of the founding father. As a youth Washington had copied out of a book “Rules of Civility” that he strove to obey, and by the time he took command of the Continental Army in 1775 he had developed a demeanor rooted in military bearing. However, he was not a stiff. “He is a complete gentleman,” Continental Congress delegate Thomas Cushing of Massachusetts wrote. “He is sensible, amiable, virtuous, modest, and brave.” Abigail Adams described Washington as having “a dignity that forbids familiarity, mixed with an easy affability that creates love and reverence.”

Washington was a courtly man whose social address and air of deference made him agreeable to all. The essence of the 18th-century gentleman was courtesy—a word derived from “court” and encompassing how one was to behave in the royal presence. To embarrass another would violate the courtly canon as well as Washington’s beloved “Rules of Civility.”

Of the reserved general’s fondness for such as Morris, a rake and prankster, Washington biographer James Flexner observes, “Washington relished scapegraces that kept him amused.” Washington himself wrote, “It is assuredly better to go laughing than crying thro’ the rough journey of life.” Disinclined to outbursts of joviality, he nonetheless relished it in others. Wrote James Madison, “The story so often repeated of his never laughing…. is wholly untrue. . .. He was particularly pleased with the jokes, good humor, and hilarity of his companions.”

The general had a soldier’s wit, earthy and sly. Long after the Revolution, a fellow veteran officer of advanced years took a wife. In a surprisingly ribald letter to a friend, Washington wrote of the bridegroom, “I am glad to hear that my old acquaintance Colo. Ward is yet under the influence of vigorous passions—I will not ascribe the intrepidity of his late enterprize to a mere flash of desires, because, in his military career he would have learnt how to distinguish between false alarms & a serious movement. Charity therefore induces me to suppose that like a prudent general, he had reviewed his strength, his arms, and ammunition before he got involved in an action—but if these have been neglected, & he has been precipitated into the measure, let me advise him to make the first onset upon his fair [lady]…with vigor, that the impression may be deep, if it cannot be lasting, or frequently renewed.”

Wayward Washington

Celebrity and sex go together like peanut butter and jelly, so it was perhaps inevitable that the catchphrase “George Washington Slept Here” would acquire shady overtones. Lately the claim is that Washington fathered a slave child, West Ford, by a concubine named Venus. Beyond Ford family oral history, there is no evidence to support this story, which first surfaced in print in 1940.

A slave named Venus was in George Washington’s orbit, but not at Mount Vernon. She belonged to the general’s brother John, who lived at Bushfield, about 50 miles southeast of Mount Vernon. When Washington went off to fight the Revolution, Venus was a child. Even putting the two together in the nine months before West Ford’s birth requires a huge leap of faith. The year of West Ford’s birth is a matter of dispute. He most likely was born in 1784 but may have arrived in 1785. The date matters. If the child was born in 1784, Washington, at war throughout 1783, could not have fathered him. If West were born in 1785, in theory Washington could have been his father—provided circumstance placed Venus and Washington together. Washington did not visit Bushfield immediately after the war’s official end in 1783. However, in 1784 John’s wife, Hannah, accompanied, according to the record, by a “maid,” briefly visited Mount Vernon. If that “maid” was the slave Venus—and there is no way to know—she and General Washington could have been in the same place at the same time.

That is the extent of the case that anyone can make; namely, that Washington and Venus could have been in the same place at the same time nine months prior to the birth of West Ford. Of course, this theory does not explain why America’s most famous man, happily married, fanatically dedicated to guarding his reputation, would dally with a

sister-in-law’s servant under his own roof. In addition, Washington fathered no known biological children; some speculate that he was sterile.

West Ford, an impressive figure who founded Gum Springs, near Mount Vernon, likely was related to George Washington. An 1858 sketch of Ford shows a man with features prominent in members of the Washington family. And in her will, Hannah Washington, who died in 1801, directed that the “lad West” be inoculated immediately against smallpox and bound to a “good tradesman” until he reached the age of 21, “after which he is to be free for the rest of his life.” We can only guess about this advocacy by John Washington’s widow and the mother of John’s sons Bushrod, Corbin, and William Augustine. The truth is uncertain, but West Ford’s father likely was William Augustine—Augustine to his family—who died at 17 in an accident involving a shotgun-wielding friend. If Augustine fathered West Ford, and if his mother knew, Hannah well could have been looking out for West’s interests as her lost boy’s child and her grandson, no matter his origins. I hear in the West Ford/George Washington story the possible echo of a Ford family narrative, told and retold, that began as the story of a child fathered by a Washington and became one of a child fathered by George Washington himself.

So Help Me, George

Controversy has arisen over whether, in becoming president in 1789, George Washington added the improvised phrase, “So help me God,” to the prescribed constitutional oath. Historians once accepted this as fact.

However, evidence makes clear that Washington did not change the oath stipulated in Article Two, Section 1 of the Constitution: “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” French foreign minister Comte Elénor-François-Élie de Moustier, who attended the inauguration, described the 1789 event in considerable detail in a letter to his superiors. De Moustier even transcribed the oath as stated in the Constitution, and in doing so made no mention of “So help me, God.”

The first published account of Washington uttering this phrase as part of his swearing in appeared in The Republican Court, an 1854 book by anthologist and editor Rufus Griswold, who said he based his account on a childhood recollection attributed to novelist Washington Irving.

Knowing this, researcher David Parker searched online databases using as a rubric “So help me, God” and the 1789 inauguration. Among multiple hits, Parker found none predating 1854 and after 1854 so many that through most of the 20th century, virtually no one, historians included, questioned that Washington introduced the phrase.

It would have gone against George Washington’s nature and experience to rewrite the constitutional text, which

originated in the 1787 Constitutional Convention that he presided over. He revered the resulting Constitution, and in many ways was a constitutional literalist. In the act of becoming the nation’s first president, such a man would not glibly alter an oath written into the nation’s fundamental charter. On that august occasion, George Washington would have acted out of political philosophy, not religious belief.

Washington never personally objected to saying, “So help me, God,” and many suggest that, caught up in the solemnity of the moment, he uttered the phrase as an improvisation—plausible, until one studies the commentary that the inauguration engendered and the context for the event itself. In April 1789, the month Washington took the oath of office, the first Federal Congress was debating, under Article Six of the new Constitution, what oath to require of federal officials. Article Six does call for an oath, but also states, “No religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.” As recommended by a committee chaired by James Madison and Alexander White, the House on April 27, 1789—three days before Washington was to be sworn in—passed a new oath act pointedly excluding use of the phrase “So help me, God.” The Senate, after adding unrelated amendments, passed the simpler House oath bill on May 5, 1789, less than a week after the inauguration, on April 30, 1789. It simply does not make sense that the Senate would have acted as it did if the great hero of the American people conspicuously added those words to his own oath—without anyone commenting on that fact.

Nobody’s Puppet

The most pernicious Washington myth is that the first president was a mere figurehead. His critics, writes Ron Chernow, view Washington as “a dim-witted tool in the nimble hands of Alexander Hamilton.” This reading can be traced primarily to Thomas Jefferson and his profound influence on generations of historians. Here is what I think happened. Washington’s policies increasingly upset Jefferson, a pattern that climaxed when Washington decided to support the 1794 Jay Treaty with Great Britain. A vexed Jefferson wondered how the man who had led the fight for American liberty could support such a blatantly poor and dangerous treaty and become the patron, however unwillingly, of oppression. Experiencing cognitive dissonance, Jefferson could only conclude that the Washington supporting Jay’s treaty—seen as favoring British interests—was not the true Washington. “His memory was already sensibly impaired by age, the firm tone of mind for which he had been remarkable was beginning to relax, its energy was abated; a listlessness of labor, a desire for tranquility had crept on him and a willingness to let others act and even think for him,” Jefferson wrote, extrapolating from disbelief to a diagnosis of senility. In private correspondence with trusted Republicans, Jefferson polished his vision of an old soldier past his prime, reading speeches he did not write and could not comprehend, a hollow hunk of his former greatness.

The notion of a senile Washington helped explain Alexander Hamilton’s powerful, if nefarious, influence on a figure Jefferson respected and longed to admire. Jefferson more easily could impute the president’s behavior to a sinister adviser’s influence than face the reality that he and Washington disagreed so fundamentally. “Washington’s blindness to the Federalist threat was born of fatigue and corrupt ministers,” historian Joanne Freeman writes. “It was surely not the result of simple disagreement, which would either depict that Hamilton’s views as a viable alternative or place George Washington among the politically damned.” Casting the aging president as a good man being hoodwinked by a conniving adviser enabled Jefferson simultaneously to admire a “deceived” Washington and oppose Washington’s “depraved” administration. The Washington-as-figurehead thesis still exerts influence despite more than 20 years of scholarship refuting that line of palaver.

We do not need a mythical George Washington. The man himself, strictly on his own terms, more than suffices. The greatest and most important figure in our country’s history requires neither inflation nor canonization. Abigail Adams was right on target when she said of Washington, “Simple truth is his best eulogy.”