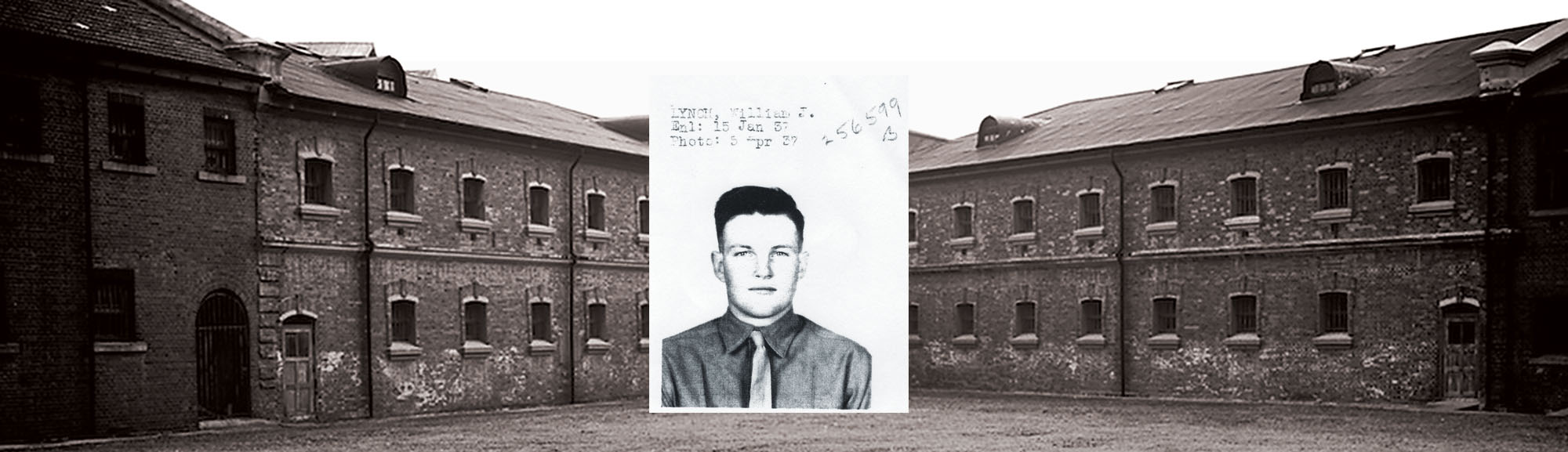

Marie Lynch kept this hand-tinted portrait of son Billy for years. (Yang Jing Research Archive)

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n 1945, near East Mountain outside Lushun, in Northeast China, stood a prison run by the Japanese army. Across the regions of China that the Japanese seized in the 1930s, the occupiers held thousands of Allied prisoners of war. But only spies, saboteurs, dissidents, and others considered threats to the Japanese overlords went to Lushun Prison, where incarceration was a death sentence. Lushun held hundreds of Chinese and Korean men—and a lone Caucasian.

Around Lushun, at the tip of the Liaodong Peninsula that juts like a thick finger into the Yellow Sea, white

faces were not uncommon. The Russians had controlled Lushun, which they called Port Arthur, until 1905, when the Japanese, having defeated the tsar’s navy, captured the city after a five-month siege. But the Westerner at Lushun in 1945 was obviously not Russian. He stood tall, about 5-foot-10, with a ruddy complexion and long nose that did not look Slavic to locals like guard Fang Zongqi, then 18, and Liu Daojing, then 16, who did odd jobs around the prison. The youths each quickly learned that the tall stranger was an American and put the foreigner out of their minds. That August, after Japan surrendered, Fang studied engineering. The Allies liberated the region’s POWs and documented the fates of prisoners who had died there. But that proved impossible for U.S. Marine Staff Sergeant William J. Lynch. In 1946, American authorities declared Bill Lynch dead and notified his mother in Dorchester, Massachusetts.

Bill Lynch was like many young fellows in Dorchester in the 1930s: Irish-American, big family, hard times. The Lynch children—Daniel, Bill, Eleanor, and Raymond—attended Sunday school at St. Ann’s, one of the factory town’s many Catholic parishes. Their father, Daniel, had grown up in Dorchester at 57 Victory Road, where their grandparents still lived. When Dan Lynch died in November 1932, his folks offered his widow, Marie, a cold-water flat at the back of their place. Marie accepted and took a night job as a nurse, assigning Eleanor to care for her brothers.

Bill Lynch grew to be a good-looking guy. He had blue eyes, brown hair, and a ruddy complexion. He was good with his hands. At Mechanic Arts High, a public school, he learned to weld. He dropped out in 1935 and joined the 26th Signal Company of the Massachusetts National Guard. A May 1936 honorable discharge describes his character as “excellent.” In January 1937, Bill Lynch enlisted in the Marine Corps and trained as a quartermaster.

Marines prized postings to China, and prized no China posting more than Shanghai, where since 1927 the 4th Marines had been protecting American interests. A Shanghai Marine could live like a mandarin. Officers could, and did, keep polo ponies, and even NCOs could afford servants and swank apartments. Except when Mao Zedong’s Communists tangled with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists, Shanghai was fairly placid. For years, the 4th Marine duty day ended at 1 p.m. That changed in 1931, when Japanese troops took over Manchuria, ostensibly to quell unrest but really to seize the heavily industrial northern region. The victors renamed the province Manchukuo, installed a puppet government, and made the area, particularly around the city of Mukden, a center for war materiél production, forcing locals to work in factories like those of Manchurian Machine Tool Company, which produced fighter plane parts.

In late November 1937, Japanese forces captured Shanghai and began harassing that city’s foreign residents. Japanese gendarmes and U.S. Marines clashed. Tensions escalated. In July 1939, after a three-month sea voyage, Bill Lynch landed at Shanghai to join the Service Company of the 4th Marines. That September, Hitler invaded Poland.

On November 27, 1941, the United States advised military commands worldwide to expect Japanese aggression “within the next few days.” On November 28, the 4th Marines sailed for Manila, 1,150 miles south. They had barely unpacked when Japan hit Pearl Harbor and invaded the Philippines, driving American and Filipino troops south to the Bataan Peninsula and then Corregidor Island. In April 1942, the main U.S.-Filipino force on Bataan surrendered and, despite fierce resistance by the 4th Marines, Corregidor fell May 8. The Japanese, who had not ratified the 1929 Geneva Convention on treatment of prisoners of war, despised everything about surrender. “To live as a prisoner of war is to live without honor,” declared Prime Minister Hideki Tojo. “In Japan,” he told his POW camp commanders, “we have our own ideology concerning prisoners of war which should naturally make their treatment more or less different from that in Europe and America.”

The Japanese regarded POWs as slaves. On August 22, 1942, Vice Minister of War Kyoji Tominaga wrote to Kasahara Yukio, chief of staff of the Kwantung Army, telling him the government wanted to expand Manchurian Machine Tool’s Mukden operation by using POWs. “We are ready to intern about 1,500 POWs from the South Seas,” Kasahara wrote in September. “We expect you to transfer POWs as soon as possible.”

Japanese troops in the Philippines were holding thousands of Americans, including Bill Lynch. His captors moved Lynch from Corregidor to Bilibid Prison in Manila, then to Camp 3 at Cabanatuan, where the sorting started. At Camp 3, “the Jap Officer began making rounds through camp jotting down prisoners’ numbers, asking questions, checking the health of the best-looking prospects for some work detail,” U.S. Army Private T. Walter Middleton, a Californian, later recalled.

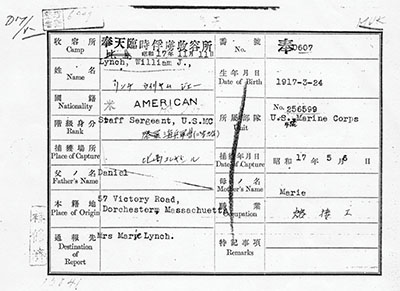

Bill Lynch’s skills—his POW identification card labels him a “welding operator”—marked him for slavery in Manchukuo. The Japanese shipped POWs aboard “hell ships” that often carried Japanese troops and supplies as well. Prisoner of war transports were not marked as such, putting Allied POWs at risk of attacks by their countrymen.

On October 6, 1942, Bill Lynch was one of 2,000 POWs crammed in the forward hold as the transport Tottori Maru departed Manila. “We were touching someone on every side and couldn’t move,” fellow POW Middleton wrote in a memoir. “My short pants were stiff and sticking to me all around my bottom with dried dung. I sat in puddles of other men’s urine and mine.”

The POWs spent the voyage, during which an American sub fired two torpedoes at the ship but missed, in that stinking hold. Thirty days and 1,500 miles later, at Pusan, Korea, most men disembarked. The Tottori Maru turned east to Japan, its remaining human cargo bound for home island POW camps whose inmates worked at mines and factories. Guards in Pusan stripped their charges, washed them down with fire hoses, and issued thin uniforms. After five weeks, during which two or three men died every day, guards shoved the survivors—Britons, Australians, New Zealanders, Dutchmen, and Americans including Bill Lynch—aboard boxcars to roll north 550 miles to Manchukuo.

When Lynch reached Manchukuo November 11, daytime temperatures were averaging 14°; at night the mercury could fall to -22°. The Japanese installed the prisoners at Hoten, an abandoned Chinese army camp near Mukden. “The barracks were buried half underground and were covered with a foot of dirt and sod,” Middleton wrote. “Walls were double and insulated with sawdust.” Two barbed-wire fences ringed the 11-acre compound, crowded with primitive barracks, kitchens, and other buildings. Between the fences was the Zero Zone. A POW entering the Zero Zone was signing his death warrant. Beriberi, malaria, pneumonia, and dysentery rampaged among the POWs. Medicine was scarce. So was food. “It was not uncommon to find a dead mouse in the cooked gruel,” Army Private Smith Merrill of Algonac, Michigan, wrote later. “When this happened, a prisoner would shout out, ‘Hey, I found some meat in mine!’” Men bunked in numerical order. Bill Lynch, Prisoner 607, slept a few pallets from Prisoner 610, fellow 4th Marine Roy Weaver of Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. When Prisoners 608 and 609 died, Bill and Roy closed the gap. No news from the outside ever reached Hoten.

POW camp IDs shrank lives to a few mean details. (Yang Jing Research Archive)

Decrepit Russian-made stoves “heated” the barracks—if the occupants could scrounge wood to feed them. That winter, at least 176 men died, their corpses stacked until spring, when POWs had to thaw the ground to bury comrades. “Digging graves for so many dead was a dreadful ordeal,” Army Private Oliver Allen of Tyler, Texas, said later. “We would get scrap lumber, each one of us with a load in our arms, and then go to the cemetery where we built a large bonfire on the spot where we were to dig. When the fire burned out, we would get busy and dig there while it was still thawed, before it froze again.”

Guards beat prisoners at will. “Every time the Japs were short on temper was an indication that they were not faring well in the war. It was an excellent barometer as to the progress of war,” Army Private Joseph Petak of New York City recalled later. “It was a painful way to find out because they were prone to use rifle butts and cuts from swords and bayonets.”

Manchurian Machine Tool Company, five miles south of Hoten, was shorthanded, so guards marched Bill and the others to the factory. The slave laborers’ first assignment, to their disgust and amazement, was to fashion concrete bases for brand-new American-made machinery. At every chance, POWs sabotaged gear. “Bolts were unscrewed; knobs, handles and flywheels disappeared,” wrote Merrill. “The prisoners finished the foundations and secured the machinery but it was totally useless.” The prisoners nicknamed their workplace, MKK; its name in Japanese was Manchu Kikai Kosaku Kabushiki Kaisha.

In January 1943, Bill’s younger sister Eleanor married Harold Armour, a Navy man, at St. Ann’s. In March, a letter from the Marines arrived at 57 Victory Road confirming that Bill was a POW, serial number 256599. This was a relief to his mother, who had feared the Bataan Death March had claimed her son. His location could not be ascertained, the letter said, but Marie could write to Bill in care of the Japanese Red Cross, Tokyo, Japan. Inquiries about his welfare were to go to the War Department.

In a May 11, 1943, telegram signed by Marine Corps Commandant Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb, Marie was told: “Your son Sergeant William Lynch was performing his duty to his country in the Manila Bay area when that station capitulated. He will be carried on the records of the Marine Corps as missing pending further information. No report of his death has been received and he may be a prisoner of war. It may be several months before definite official information can be expected concerning his status.”

Bill Lynch was not a model prisoner. Once, for talking back at MKK, he drew 15 days’ confinement. Escape was futile. Half a world from home, obviously out of place, prisoners knew that the men left behind would suffer and that recapture meant torment or worse. Even so, after dark on Monday, June 21, 1943, three Americans cut the wire at Hoten and made for Soviet-controlled Mongolia, 560 miles north. Hiding by day and hiking by night, the trio spent 11 days at large. Searchers caught them at the edge of the Gobi Desert. “They were brought back to the camp, and paraded to the other prisoners,” wrote Merrill. “The Japanese officer stuck his thumb high in the air. The message was that the Americans stand out like sore thumbs in any Oriental groups. You cannot escape without being caught.” The Japanese executed all three.

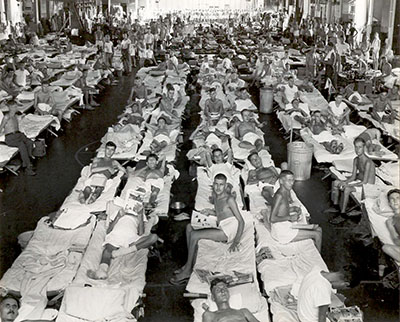

Starved, battered prisoners came home aboard the USS Block Island. (American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor Memorial Society)

To squeeze more work out of prisoners, their captors built a camp half a mile from MKK—another mark of Japanese scorn for the Geneva Convention, which banned siting POW camps within two miles of factories and other military targets. The compound, behind a 7-foot brick wall topped by high-voltage barbed wire, squeezed into its acre-plus guardhouses, three POW barracks, a barracks for Japanese troops, and a headquarters. The Manchurian Leather Factory, a tannery that processed material for boots, was the first Mukden war plant to have on-premises slaves: Bill Lynch and 150 other men relocated from MKK. They lived inside a 10-foot wood-and-barbed-wire fence.

Tanning determines leather’s toughness. Hides from Manchurian Leather were supposed to be dense and durable, but POW crews diluted or contaminated the chemicals, making the material useless. “Sometimes we’d write graffiti on the leather,” Army Private Hearshel Boushey of Camano Island, Washington, recalled.

Bill Lynch lost patience. On the rainy evening of Wednesday, May 17, 1944, guards counted him at roll call. Around midnight a bed check revealed that “Lynch, William, Prisoner 607” had vanished. The duty officer phoned the commander. An emergency roll call triggered an alert to the military police. Within 30 minutes, searchers were circulating, especially at Huanggutun Train Station, three miles away.

Bill eluded his pursuers, and by 11 the next morning had traveled more than 12 miles southwest. Near Masanjiazi, a villager spotted the Westerner, told police, and with neighbors detained him. Word spread quickly. “I later learned from my neighbor villagers that a white American was wounded in the leg by gunshot and captured in the vicinity of Masanjiazi,” recalled Tan Yuzhen, then a 15-year-old apprentice well digger.

Bill had fled on impulse, camp personnel reported. After roll call, he had feigned sleep, then changed into summer fatigues. Around 11 p.m., he went to the latrine, where he scaled the fence. He used scrap lumber to traverse the wire encircling the factory. His feat earned the other POWs a scolding, and his seven-man squad spent a week in the guardhouse standing at attention from 5 a.m. till 11 p.m., with minimal rations. Roy Weaver last saw Bill Lynch at the main camp in Mukden. “He was brought back on a stretcher, and was carried off,” Weaver said later. “However, at every roll call from that time on he was carried on the rolls as being in a military prison.” Camp authorities put Lynch on trial and on June 6, 1944, convicted and sentenced him to seven years’ hard labor. No one at the tannery saw him again. That December, B-29s raiding Mukden bombed the camp, killing 19 POWs and wounding dozens.

Marie Lynch never gave up hope. In her bedroom at 57 Victory Road she kept photos of her Marine, Billy, and her soldiers, Daniel and Raymond. On Saturday, April 14, 1945, she sat with a copy of War Department Provost Marshal General Form No. 112, a flimsy airmail sheet that folded to become its own envelope. With a pencil Marie Lynch checked the box indicating Bill’s nationality below the label reading “Prisoner of War Post” in Japanese, German, and French.

“DEAR BILL,” Mrs. Lynch printed in the requisite block capital letters. “HOW ARE YOU WE ARE ALL FINE. EALEANOR [sic] IS BACK HOME. UNCLE GEORGE IS VERY SICK. WHY DON’T YOU WRITE. WRITE SOON. LOVE FROM ALL MA.”

The letter, postmarked April 16 in New York City and cleared by U.S. Censor 11951, came back stamped “RETURN TO SENDER UNDELIVERABLE AS ADDRESSED.”

By the time Japan surrendered, more than 17 percent of the POWs at camps in Mukden had died, a relatively low percentage attributed to the fact that the main facility, a model camp, was visited by higher-level officials. Death rates were much higher among Asian prisoners and Allied POWs sent to factories as slave laborers. Survivors, including U.S. General Jonathan Wainwright, captured in the Philippines, and British General Arthur Percival, taken at Singapore, were liberated by Allied troops who tried to account for every man. Japanese records and camp staff testimony indicated that after Lynch’s trial he had likely been moved to Lushun Prison. In September 1945, a joint U.S. Army–Marine Corps search party traveled 240 miles down the Liaodong Peninsula to Dalian, a seaport in Liaoning Province near Lushun. Bill Lynch’s trail led there, then dwindled to nothing.

In a May 24, 1946, letter to Mrs. Lynch, the Marine Corps wrote that efforts to locate Bill, including a search of all Japanese camps and records, had turned up no trace. Bill was presumed dead. “The conclusion is inescapable that he lost his life in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in Manchukuo,” a lieutenant colonel wrote. “I realize that there is nothing I can say to comfort you, but I hope you will find consolation and pride in the fact that your son did his part in helping to bring this war to a successful conclusion, and that the knowledge of his patriotism and unselfish contribution toward a better world in the future will sustain you in your grief.” The Marines sent Bill’s medals: a Purple Heart, the Army Distinguished Unit Badge with oak leaf cluster, the China Service Medal, the American Defense Service Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and the Philippine Defense Ribbon—each with a bronze star—and the Victory Medal. On June 18, 1946, the First Naval District in Boston declared Bill Lynch dead. He was the only prisoner of war among about 2,000 at Mukden unaccounted for.

A Mrs. Morey, who lived in nearby Medford, Massachusetts, phoned Marie Lynch. Mrs. Morey was excited. Her soldier son Edward, listed for years as MIA, had been a POW at Mukden. “There are three local boys in camp with me. Two of them are Army and the other is a Marine,” Ed Morey wrote in a letter to his mother. “The Army boys are Moore from South Boston and Gerry from Dorchester. The Marine is Bill Lynch, from Victory Rd. Dorchester. What a guy he is! I’ll tell you all about him when I get home.”

But nothing came of the Morey connection. Dan and Raymond Lynch mustered out. The Allies hanged Tojo. Dan became a psychologist. Ray worked in Boston. Eleanor and Harold Armour had four children. Marie Lynch contacted American occupation authorities in Japan. In October 1948, the Far East Command replied, “A careful search of the records of General Headquarters and the Japanese Government Prisoner of War Information Bureau reveals only the fact that your son was interned in the prisoner of war camp in Mukden, Manchuria.” The Communists became the masters of China. Manchuria became Northeast China. Mukden became Shenyang. In 1957, Dorchester named a square up the hill from 57 Victory Road, where Marie Lynch still lived and where the water in the back flat still ran cold, for Bill Lynch. At the dedication, Marie and daughter Eleanor sat dry-eyed. In time, the Lynch family gave up the house, and Marie moved into an apartment that did have hot water. A stroke sent her into a nursing home. In 1969, the city demolished 57 Victory Road. Marie Lynch died in 1981. She was 93. Her boy Bill would have been 61.

Liu Daojing and Fang Zonqi, who as youths had worked at Lushun Prison, grew to manhood. Liu farmed, Fang worked in a textile mill. During the Cultural Revolution, their servitude to the Japanese brought them much trouble, but they underwent political rehabilitation and retired in peace. In 1980, the city of Shenyang founded a university, whose faculty decided Mukden’s war years deserved attention. In 2007, the Mukden Allied POW Camp Studies Program reopened the case of Staff Sergeant William J. Lynch. Researchers studied oral histories and documents from Dalian residents. They read former POWs’ statements about Sergeant Lynch and Liu’s and Fang’s reports that at Lushun in 1945 they had seen a lone American among the incarcerated Asians. This and other testimony, such as Tan Yuzhen’s recollection of hearing about Bill Lynch’s recapture, led a team in 2010 to East Mountain, near where Lushun Prison once stood. Halfway up the slope is a flat stretch apparently used as a burial ground. Chinese and American historians and forensic experts have worked there without definitive result. But hope remains that by using Lynch family members’ DNA, someone will positively identify the remains of Staff Sergeant William J. Lynch, the lost China Marine. ✯

This story was originally published in the November/December 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.