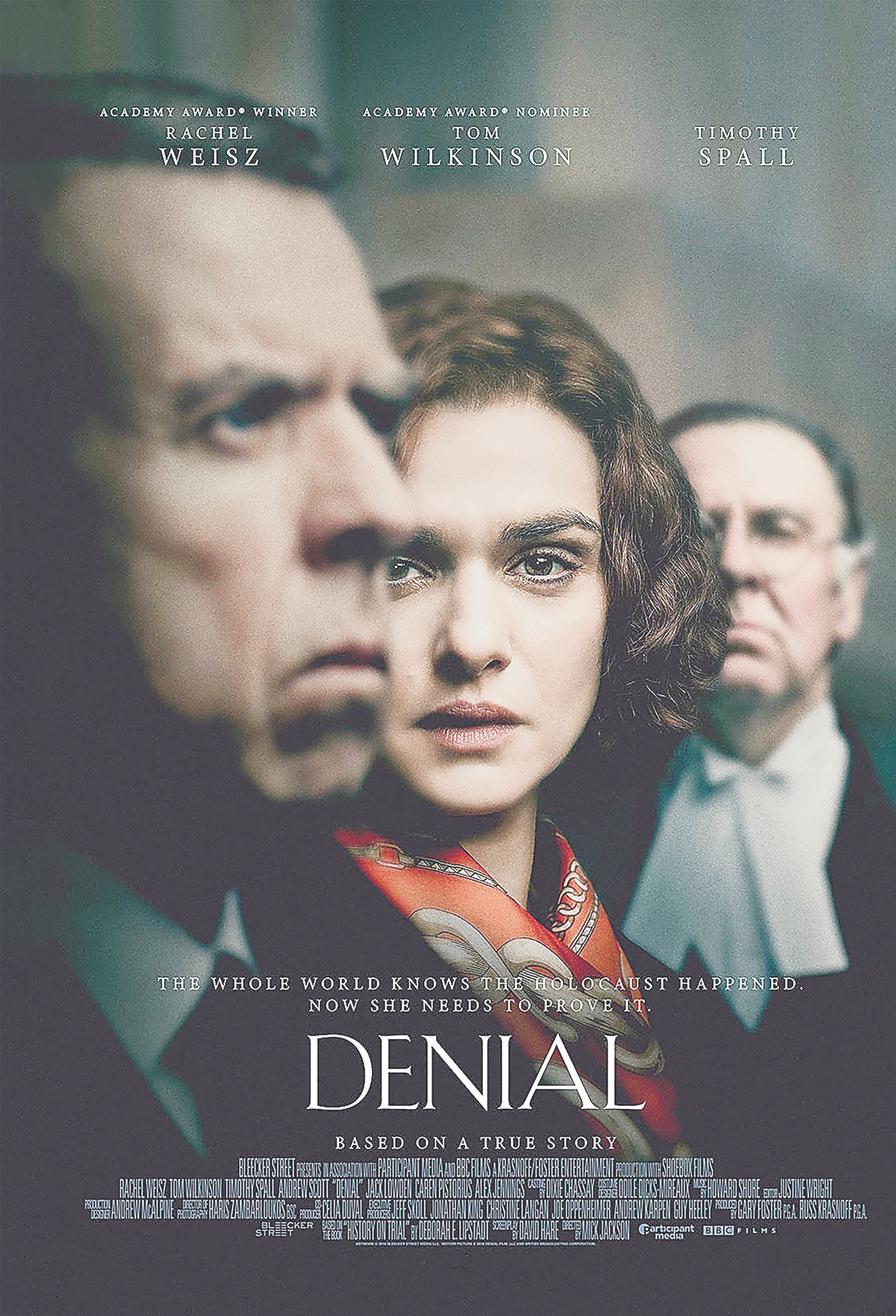

When we think of passion, we think of something akin to ardent conviction. That’s the kind of passion exemplified by Emory University professor Deborah Lipstadt, a historian of the Holocaust whose book, Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory, made waves when published in 1993. It also brought a lawsuit for libel from David Irving, a once-respected historian turned Holocaust denier singled out in the book. Directed by Mick Jackson and released in 2016, Denial tells the story of the remarkable courtroom battle that followed.

In the film, as in life, Irving (portrayed by English actor Timothy Spall) files suit against Penguin Books, the London-based parent company of Lipstadt’s book publisher, the New York-based Free Press. It’s a shrewd move by Irving, for British libel laws differ from those in the United States: in the States, the plaintiff must prove that the defendant’s claims are not just inaccurate, but malicious. In Britain, the onus is on the defendant to demonstrate that their claims are both accurate and that the plaintiff knowingly distorted the facts.

This requires Lipstadt’s attorneys—or more precisely, those employed by Penguin Books—to prove two things: first, that the Holocaust occurred; and second, that Irving deliberately distorted evidence in an attempt to prove that it didn’t.

Lipstadt (Rachel Weisz) flies to London to meet with her extensive legal team. In many respects, they are an impressive lot, led by Anthony Julius (Andrew Scott), the solicitor chiefly responsible for preparing the case, and Richard Rampton (Tom Wilkinson), the barrister who will present the case in court. In one respect, however, they arouse Lipstadt’s ire: they won’t let her testify. They also won’t let Holocaust survivors testify. In both cases, the legal team fears that they would simply give Irving—who, arrogantly, is representing himself—the opportunity to grandstand and, in the bargain, humiliate victims who have suffered enough.

Lipstadt can scarcely believe it. Nor can she fathom the dangerous possibility that without exceptional care in presenting their evidence, Irving stands a good chance of making his case that mass murders at Auschwitz—and by easy extension, the Holocaust—did not happen. For one thing, the Nazis permitted no photographs of the killings at Auschwitz (or at any other death camp). For another, they dynamited its gas chambers in 1944, and again in 1945. Such quibbles don’t matter to Lipstadt; the truth of the Holocaust is so obvious that no serious person could deny it. Yet any person, Holocaust denier or not, is entitled to equal justice under law. Her attorneys grasp this, even if she can’t.

Thus, when Lipstadt and some legal staff, including Rampton, visit Auschwitz, Rampton’s attitude is seemingly the polar opposite of hers. He arrives late for the rendezvous outside Auschwitz, an act of disrespect that offends Lipstadt, and cuts short a museum guide who describes Auschwitz as the “most efficient killing machine in human history.”

“Yes, we know what it is,” Rampton snaps. “It’s how we prove what it is. We’re not here on a pilgrimage. We’re preparing a case.”

Later, in the trial’s early stages, Lipstadt encounters a Holocaust survivor who says that she and other survivors must be allowed to testify on behalf of the millions of dead who cannot speak. Lipstadt assures her that “the voice of suffering will be heard.” But when she tells Julius, the case’s solicitor, that she has made this promise, he is implacable. “A trial, I’m afraid, is not therapy,” he retorts. And as for her promise: “You had better go back out there and break your promise.”

Not until the trial nears its climax does Lipstadt begin seeing what is really going on. Julius and the staff, in preparing the case, have armed Rampton with all he needs to demolish Irving. Again and again, Rampton invalidates Irving’s deliberate inaccuracies, his sophistries, his contentions that Zyklon B, an insecticide used to slaughter over a million victims, was really used only to treat the lice-infested corpses—never mind that the corpses were immediately cremated—and that evidence showing that humans had occupied the gas chambers merely reflected that the chambers did double-duty as air raid shelters for SS personnel. Here the reason for Rampton’s tardy arrival at their Auschwitz rendezvous becomes clear: he was pacing the distance from the SS barracks to the gas chambers, over two miles, to show the absurdity of Irving’s explanation.

And throughout, as he thunders away, Rampton deliberately avoids looking straight at Irving, as if Irving were so loathsome that one could scarcely lay eyes on him. In the end, Irving not only loses his case but is utterly discredited.

Denial demonstrates that there is more than one kind of passion: there is the passion of Lipstadt, all afire with fierce certainties; and the passion of attorneys, devoted to the law and what the law, when properly used, can accomplish. Indeed, there are all sorts of passions in the world. And we need them all. ✯

This article was published in the February 2022 issue of World War II.