In the summer of 1941, Franciszek Gajowniczek, a Polish soldier, was one of thousands held prisoner in the Nazi death camp of Auschwitz. There, the difference between life and death often remained up to the macabre game of chance.

In July, that gruesome day arrived for the soldier. Gajowniczek was one of 10 men arbitrarily selected by the German command to die by starvation in retribution for the escape of a prisoner the previous day. (The man who had disappeared was later found drowned in the camp latrine, according to the Jewish Virtual Library.)

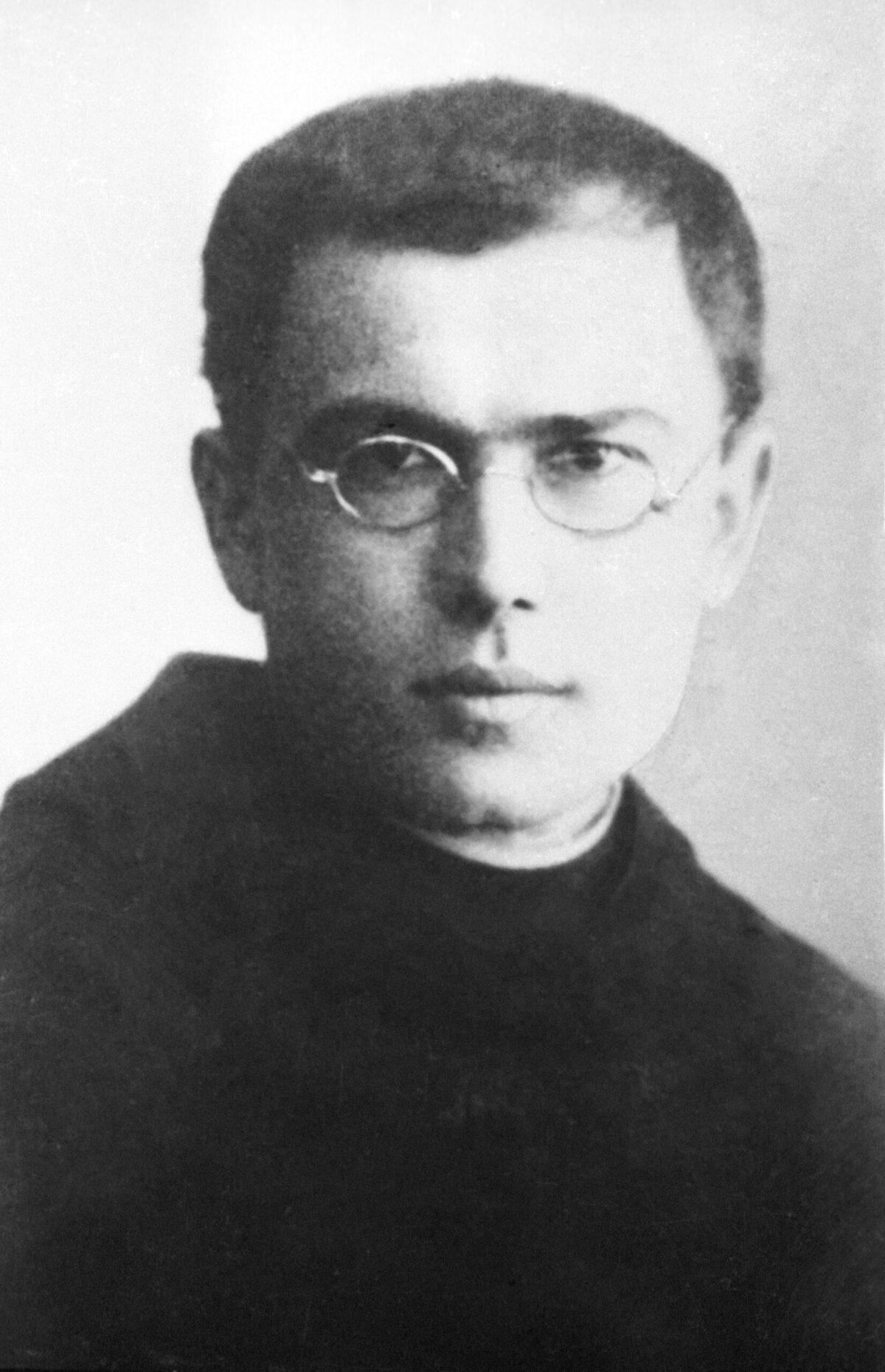

That morning as he heard his name called, the 41-year-old soldier reflexively cried out for his wife and children. Seconds later, writes the Washington Post, “a Polish Franciscan monk stepped from the line — an action for which he might have been shot on the spot — and asked, in perfect German, for a favor.”

“I want to die in place of this prisoner,” the monk, Maximilian Kolbe, reportedly said. “I have no wife and no children. Besides, I’m old and not good for anything.”

The Germans granted the 48-year-old priest’s request and led him away to his certain fate.

Gajowniczek later recalled, “I could only thank him with my eyes. I was stunned and could hardly grasp what was going on. The immensity of it: I, the condemned, am to live and someone else willingly and voluntarily offers his life for me — a stranger.”

“I was put back into my place without having had time to say anything to Maximilian Kolbe,” he continued. “I was saved. And I owe to him the fact that I could tell you all this… It was the first and the last time that such an incident happened in the whole history of Auschwitz.”

Despite the conditions in the prison cell, the priest clung to life, leading the other men in prayer and hearing confessions and giving absolution for over two weeks. On the 15th day, however, the Nazis, in need of the cell for other prisoners, injected carbolic acid into Kolbe’s veins, instantly killing him.

Before his imprisonment, Kolbe was a superior of the City of Mary Immaculate and director of Poland’s chief Catholic publishing complex. In 1938 he started a radio station and was highly vocal about his anti-Nazi views. Kolbe was arrested a year later by the Gestapo but was released soon after.

As war broke out, Kolbe and the brothers at his friary in Niepokalanów, Poland provided shelter to an estimated 2,000-3,000 refugees, the majority of them Jews attempting to escape Nazi persecution.

For his actions, Kolbe was once again arrested on February 17, 1941, and in May of that year he was transferred to Auschwitz where he perished along with 1.1 million others.

On October 17, 1971, Kolbe became the first Nazi victim to be beatified by the Roman Catholic Church. Eleven years later the priest was canonized by Pope John Paul II.

Gajowniczek — who survived Auschwitz — attended both ceremonies.