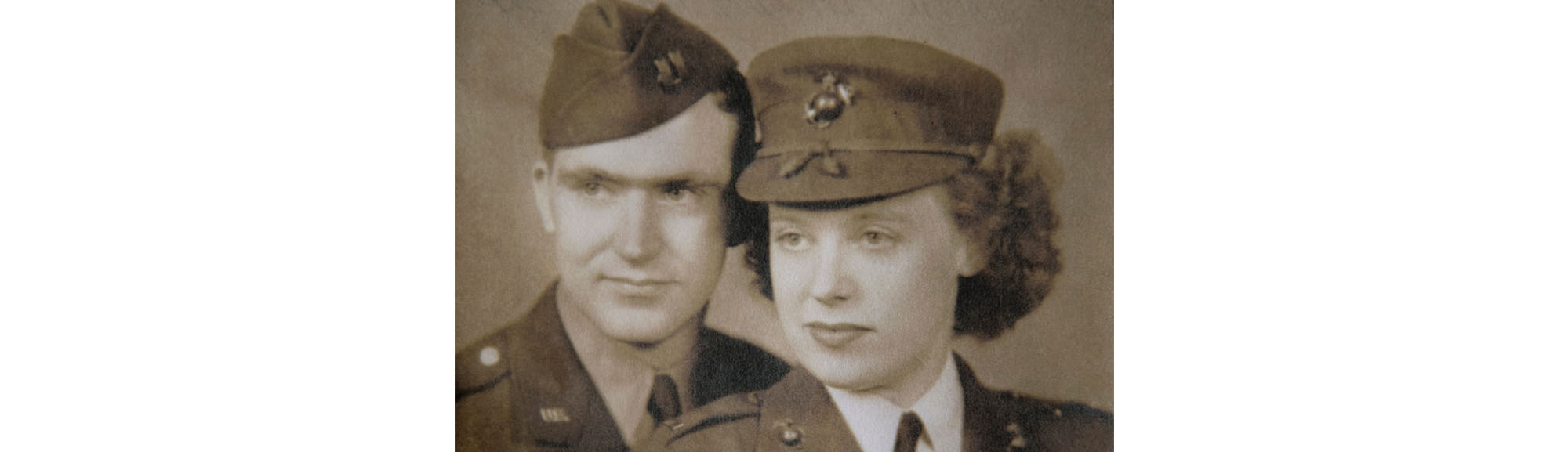

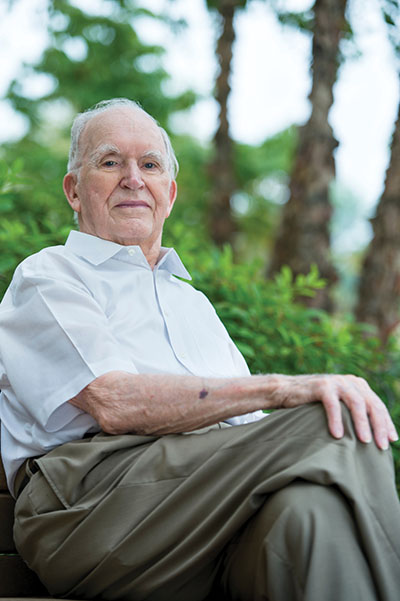

Bob Balkam, 95, grew up on the South Shore of Massachusetts. Between graduating from high school in 1938 and enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1942, he delivered newspapers, worked at a theater on Cape Cod, and drove for a salesman whose route included New Orleans, where Balkam met Laurin Cooper; they married just after he joined the army. After boot camp Balkam sailed aboard the Queen Mary to Britain where, as a private, he tested into Officer Candidate School and trained as an air traffic controller. Laurin enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps, made lieutenant, and was assigned to the Commandant’s office in Washington, DC. On June 16, 1944—D+10—Balkam’s unit landed at Omaha Beach to take over landing field A-1, carved from an orchard overlooking the English Channel.

What was going on at A-1 when you arrived?

C-47s were flying in small-arms ammunition. A C-47 could land in 1,500 feet—half the length of our runway, which was made of wire mesh. We would tell pilots to go to the end and turn around. They never did. They would get halfway—near where our control truck sat—and lock a wheel and turn. Those locked wheels broke the mesh every time, which meant we would have to stop flying and bring in the engineers to repair the runway mesh.

You arrived on D+10, but traces of D-Day remained.

Men who had drowned that first day had sunk, then surfaced. Along the shore below the field, bodies were floating. Pilots with the 366th Fighter Group, which we supported, collected scrap wood and got aviation gas and burned the bodies. They did that a couple of times.

Describe your “control tower.”

We had one-ton trucks with a box behind the cab where we worked. Our unit was given this beat-up one-ton truck; an enlisted man built the box. He scrounged a Plexiglas dome from a B-26 bomber so we could see out. It was a two-man operation. One man was at the desk with telephones; I was looking through the dome for planes and manning five radio channels—at the squadron and group levels and theater-wide.

American bombs were a big problem.

The P-47 carried two 500-lb. bombs. A little propeller at the nose triggered the detonator by spinning. To use the bombs, pilots would fly about 15 miles east to the front at Saint-Lô. Often dust from the runway would clog the release and cause a bomb to hang. Before landing, pilots with hung bombs were supposed to go out over the Channel and shake them loose. That didn’t always happen. Every time someone landed with a hung bomb, it would come loose and skid into the dirt. The bomb squad would disarm the bomb and the tech sergeant would come back and say, “Well, Lieutenant, two more revolutions and that one would have gone off.” Three to six times a day bombs would go off near our truck. Fortunately that blast goes up at an angle, and we were under it.

Did you have to worry about mines?

Yes, the Germans had mined the whole area. Engineers took out enough of them to lay the airstrip, but left the rest of the mines in place. We knew where they were. Once, a P-38 Lightning came in damaged and ended up in a minefield. We told the pilot about that. He walked out without triggering an explosion.

Did the top brass ever make an appearance?

On June 29, 1944, General Dwight Eisenhower was making his first trip to the beachhead, and General Omar Bradley had come by road to meet him. He and I were in the truck for a couple of hours, making small talk. When General Eisenhower’s plane landed, I followed General Bradley and heard him tell Eisenhower that Cherbourg had just fallen.

You listened in on the tragedy at Saint-Lô.

The day of the breakout I was on the radio overhearing ground controllers scream to bomber pilots that they were dropping too close and killing our own troops. That was the incident that killed General Lesley McNair.

How much of a strain was the job?

On an afternoon shift, 1 to 5 p.m., I would smoke a pack of cigarettes and not remember smoking one.

As the war moved east, you did too.

Some positions were better than others. At Laon-Couvron, our place looked like a quartermaster’s champagne depot. I was chasing champagne with cognac or cognac with champagne. The only thing that stopped it was when a cork would break off before you got the bottle open.

There was another plus.

Pilots there did not have to land on mesh; there was a German-built concrete runway with taxiways and primitive buildings.

Then there was Asch, Belgium.

We were at airfield Y-29 at Asch during the Battle of the Bulge. If the Germans took Antwerp, we would be cut off. My brother, Gil, was a civilian accountant attached to the armed forces in Paris. It was going to be my third Christmas overseas, and I was missing my family. I got informal permission to go to Maastricht, Holland, and catch a ride to Paris. At Maastricht, wearing my dress uniform, I went to headquarters, where every GI was in battle dress. The Germans were taking GI uniforms off corpses and posing as Americans, so any variation in appearance was suspect; I stood out like a sore thumb. “Pardon me, Lieutenant, where are you from?” a second lieutenant asked. “Massachusetts,” I told him. He asked if so-and-so hadn’t just been elected to the Senate from there. No, I said, that was in Tennessee; we elected so-and-so. He was very embarrassed.

But you made it to Paris.

The vehicle I was in, a command car, almost immediately ran off the road, but the driver got it free and we reached Paris around 7:45 p.m. My brother’s landlady let me in. A few minutes later Gil arrived. “What the hell are you doing here?” he yelled. I said, “I came to spend Christmas with you.” “Don’t you know there’s a curfew?” he says. “Anyone on the streets after 8 p.m. is presumed to be a German.” I had just made it.

Where were you when the Germans surrendered?

In Münster. Not long after, an investigator came to our base asking about a certain P-47; our records showed a ferry pilot had taken it. Once the plainclothesman decided I was telling the truth, he told me the plane had been seen flying under the Eiffel Tower. Every time I was in Paris after that, I would look at the tower and wonder why a damned fool would try such a thing.

How did you and Laurin reunite?

I mustered out at Fort Devens, Massachusetts. We agreed to meet at Union Station in Washington the day after Thanksgiving. We weren’t sure we’d recognize one another; when we parted she was a civilian and I was a buck private, and now we were both lieutenants. Through Marine headquarters she had booked us a room at the Statler Hotel and had gotten tickets for the Army-Navy game, which was that Saturday. We met on the platform at the train station, and we had no trouble finding one another. ✯

This story was originally published in the January/February 2017 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.