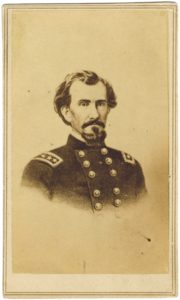

On a misty Kentucky morning, Confederate Brig. Gen. Felix Kirk Zollicoffer’s body lay on the muddy ground surrounded by gawking Union Army soldiers. “What in hell are you doing here?” a Federal officer shouted at the men as the Battle of Mill Springs swirled on January 19, 1862. “Why are you not at the stretchers bringing in the wounded?”

“This is Zollicoffer,” one of them replied, gesturing toward the corpse.

“I know that,” the officer said. “He is dead and could not be sent to hell by a better man, for Col. [Speed] Fry shot him; leave him and go to your work!”

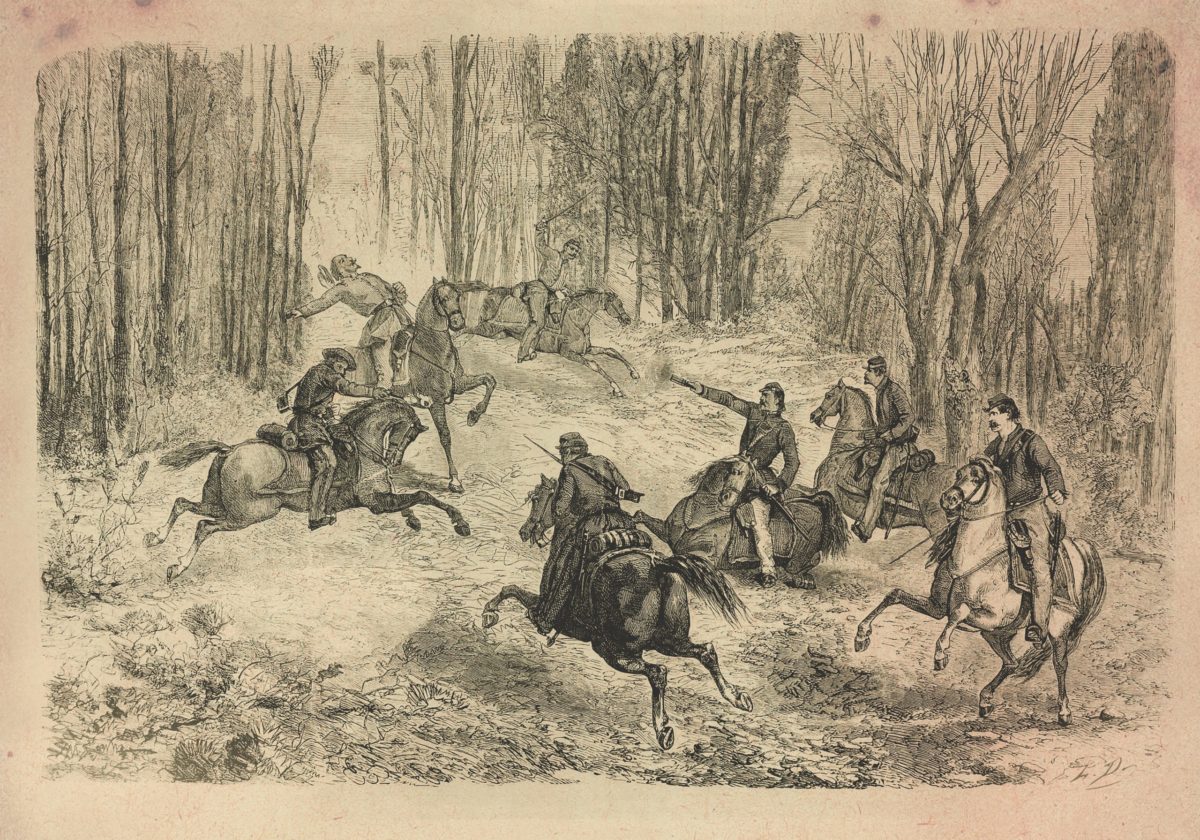

Earlier that wintry day, Zollicoffer—a former Tennessee congressman and newspaper editor from Nashville—had accidentally ridden his horse into Union lines. After a volley or two, he fell from his mount, fatally shot in the chest. Fry may have fired the bullet that killed the 49-year-old commander, derisively called “Snollegoster” and an “old he-devil” by the Yankees, but no one really knows for sure.

Even after his death, Union soldiers and others targeted Zollicoffer, whose body was looted of outer wear, buttons, hair and even (gasp!) pieces of his underwear. “Old Zolly,” though, was not the only fallen commander treated disrespectfully during the Civil War.

Fiends, ghouls, and souvenir hunters have looted fallen soldiers since the dawn of warfare thousands of years ago. Following the famed final showdown between Napoleon and Wellington at the June 1815 Battle of Waterloo, locals and soldiers reportedly yanked teeth with pliers from the fallen. But the gruesome act was not some weird form of vengeance. Early dental technicians boiled the teeth, chopped off the ends, and placed them onto ivory dentures. According to the British Dental Association, “Waterloo Teeth” appeared in dental supply catalogs well into the 1860s.

At Gettysburg in July 1863, soldiers from both sides grabbed trophies from the dead. When a 14th Connecticut soldier stooped to examine a fallen Confederate, a Pickett’s Charge victim, he noticed the curly-haired, young man held something in his hand, near his left breast. The soldier broke the Rebel’s death grip and examined the object, a daguerreotype of a young woman in her late teens or early 20s. “I prize it as the most valuable relic of my war experience,” he recalled years later.

Civilians recovered souvenirs from Gettysburg’s fallen, too. Abby Howland Woolsey wrote of her mother, who collected battle mementos from Confederates while she served as a nurse: “One, of a rebel lieutenant who died in her care; and a score of palmetto buttons from [South Carolina] rebel coats—dirty but grateful, poor wretches; etc.”

In his classic Civil War memoir, Co. Aytch, Confederate soldier Sam Watkins—who seemed to be everywhere in the Western Theater—wrote of his attempt to snatch boots from a fallen Federal colonel:

“He had on the finest clothes I ever saw, a red sash [cloth belt] and fine sword. I particularly noticed his boots. I needed them, and had made up my mind to wear them out for him. But I could not bear the thought of wearing dead men’s shoes. I took hold of the foot and raised it up and made one trial at the boot to get it off. I happened to look up, and the colonel had his eyes wide open and seemed to be staring at me. He was stone dead, but I dropped that foot quick. It was my first and last attempt to rob a dead Yankee.”

Perhaps Watkins would have tried harder if the man were a general.

In a driving rainstorm at the Battle of Chantilly (Ox Hill) late in the afternoon of September 1, 1862, Union Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny, who lost his left arm during the Mexican War, reconnoitered ground before his division. “The General rode up to a whole company of the enemy, paid no attention to their demand that he surrender, wheeled his horse and started back,” an aide recalled.

A Confederate company fired a volley, and a bullet pierced the 47-year-old general’s back, near the spine, killing him instantly. Confederates took Kearny’s body to a field hospital. The next day, the general’s remains were returned to the Union Army—minus his “sword, pistol, watch, diamond brooch, finger rings, and the pocket book, in which the millionaire general always kept a large amount of money.” Confederates snatched souvenirs from the man they called “The One-Armed Devil.” The Rebels had Bayard, Kearny’s prized horse, too. Meanwhile, Army of Northern Virginia commander Robert E. Lee burned the papers found with the general, assuming they were of a “private nature.”

Four days after his death, Agnes Kearny wrote a letter to Lee seeking the return of her husband’s mount and sword. “Feeling great sympathy” for the widow, Lee—who admired Kearny—replied on September 28, 1862: “I inquired particularly if his person had been disturbed and was informed that his uniform did not appear to have been disturbed; but that he was lying under care of a guard in the condition in which he was brought from the field without his side arms and hat.”

After Lee consulted with his government, Confederates returned Kearny’s sword—“a light one with a leather scabbard suitable for a disabled person.” It was private property of a former fellow officer, Lee decided. Rebels sent Bayard and Kearny’s saddle through the lines for Army of the Potomac commander George B. McClellan to forward to Agnes. “I beg you to accept my thanks for your courteous and humane attention to the request of the widow of this lamented officer,” McClellan wrote Lee. But the rest of the booty snatched from Kearny remained with the Army of Northern Virginia.

On July 3, 1863, Confederate Brig. Gen. Richard B. Garnett was killed during Pickett’s Charge. Although he wore a nearly new uniform coat with a general’s star and wreath on the collar, high-top boots, and spurs, the remains were never publicly identified, and his final resting place remains unknown. “Inexplicable,” Confederate veteran James Clay, Garnett’s orderly, said decades later.

“General Garnett was gallantly waving his hat and cheering the men on to renewed efforts against the enemy,” recalled Clay, an 18th Virginia private. “I remember that he wore a black felt hat with a silver cord. His sword hung at his side.”

After Clay fell among rocks, he lost sight of the 45-year-old commander during the “life and death struggle” with Union soldiers. Then Garnett’s wounded black charger, its right shoulder apparently shot off by Union artillery, galloped out of the battle smoke.

“At this time a number of the Federals threw down their arms and started across the field to our rear,” Clay recalled. “Two of these deserters came to the clump of rocks where [a Confederate captain] and I were and asked to be allowed to assist us to our rear, obviously for mutual safety, and the kind proffer was accepted. These men told us that our brigade general had been killed, having been shot through the body at the waist by a grape shot.”

Rather than attempting to recover Garnett’s body and accoutrements in the extreme chaos, Clay sought medical attention at a field hospital for his shot-off right index finger and head wound. “The place was like a slaughter pen—legs, arms, hands, etc., all piled up,” he recalled.

A Confederate staff officer reportedly recovered Garnett’s watch, but the ornately inscribed saber remained with the general’s body. Years afterward, George H. Steuart, who commanded a Confederate brigade at Gettysburg, purchased the then-rusty relic in a Baltimore junk shop. After Steuart’s death, the general’s nephew acquired the saber. He eventually gave the “precious heirloom” to Garnett’s niece.

Whether a Johnny Reb or Billy Yank picked up the relic from Garnett is unknown. How it ended up in a Maryland junk shop remains a further mystery. What’s indisputable is the location of the relic today: The American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Va.

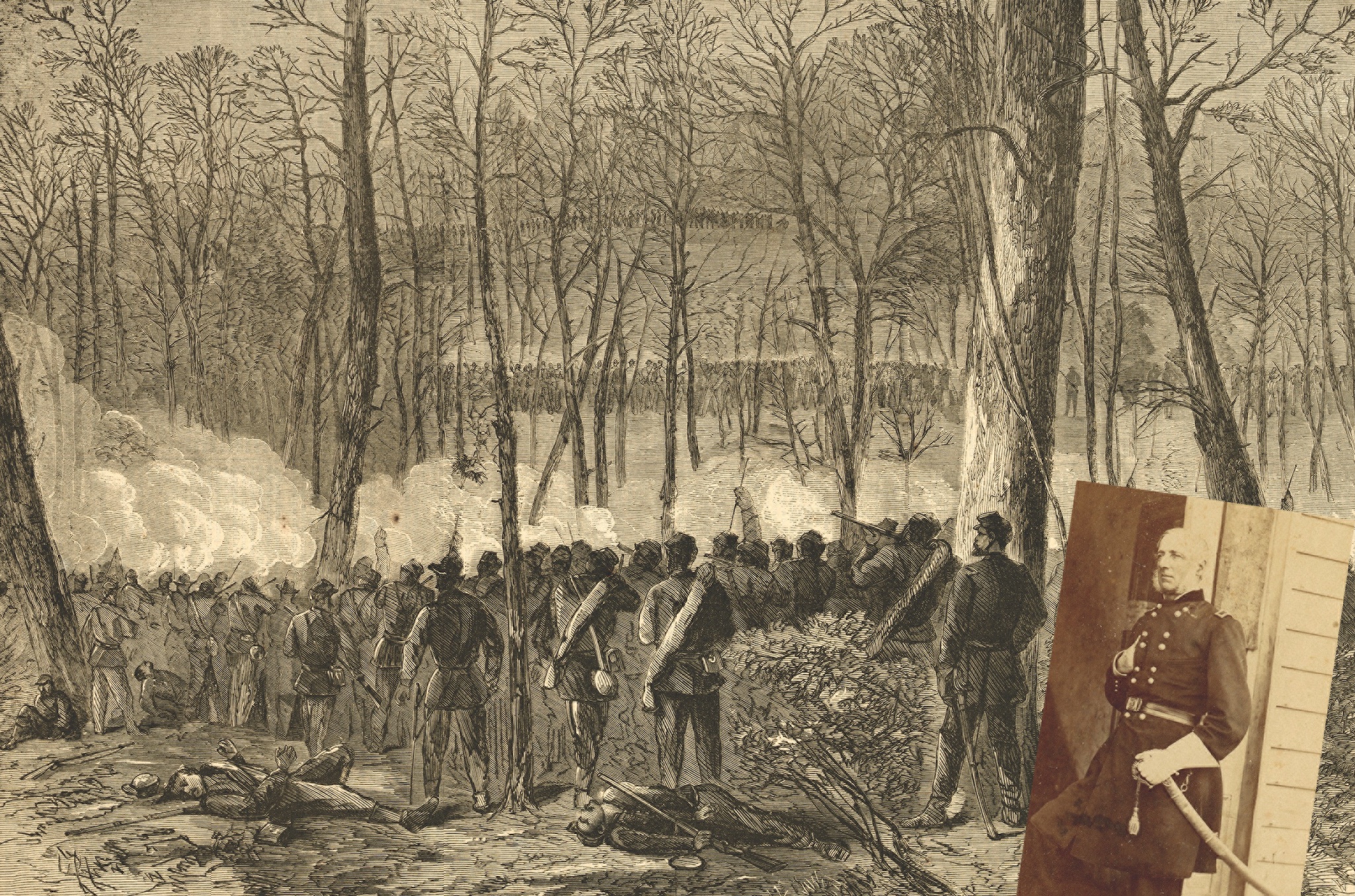

At the Wilderness on May 6, 1864, Union Brig. Gen. James Wadsworth suffered a similar fate as Kearny. As Confederates pressed an attack near the Plank Road, a bullet crashed into the back of the silver-haired millionaire’s head, splashing brains upon an aide’s coat. The aide frantically tried to remove a gold watch from the 56-year-old officer’s outside coat pocket. But as Confederates swarmed the area, he did not have time. So, he scrambled upon the general’s horse and rode like hell back to Union lines.

Like frenzied locusts ravaging a cornfield, Confederates looted the helpless Wadsworth, who died two days later in enemy hands. His sword, boots, buttons from his coat, the gold watch, a Virginia map, silver spurs, a billfold containing $90, and elaborately engraved field glasses all disappeared during the maelstrom. Confederates left the white cotton stockings with Wadsworth’s initials stitched in red thread on the general’s feet.

Shortly after the war, a Confederate veteran returned the watch to the Wadsworth family and was rewarded handsomely. Veterans later returned other items pilfered from the general at the Wilderness. But the engraved field glasses—perhaps the most prized Wadsworth booty of all—remained MIA after the war. In 1921, Confederate Veteran magazine ran an obituary of William T. Lowry, an 8th South Carolina private, who claimed to have shot Wadsworth. Lowry reportedly once had the field glasses in his possession, but the elaborate artifact supposedly had been destroyed in a fire at his house several years earlier.

In the 1970s, however, the field glasses resurfaced when a descendant of a South Carolina soldier showed the relic to a National Park Service historian during a visit to the Fredericksburg (Va.) area battlefields. He claimed his grandfather had shot Wadsworth, but the man was uninterested in donating the field glasses or leaving his name.

In 1985, James Wadsworth Symington—the general’s great-great-grandson and a former Missouri congressman—placed ads in South Carolina newspapers seeking the gloves the general wore and field glasses he carried at the Wilderness. But the long-shot effort turned up nothing, and the whereabouts of the relics remain a mystery.

After a sharpshooter’s bullet struck 6th Corps commander Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick in the cheek, killing him instantly, blood spewed “like a fountain” and saturated bushes in the undergrowth. Word of the 50-year-old general’s death spread “like an electric shock” throughout the Union Army. Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade and other officers wept over the death of a general soldiers fondly called “Uncle John.” Sedgwick’s shooting rocked overall Union commander Ulysses S. Grant as much as news of President Lincoln’s assassination the following year.

Lieutenant John G. Fisher of the 14th New Jersey saved a souvenir of the killing, cutting down a bush upon which Sedgwick bled, letting it dry in the sun, slicing off a five-inch section that formed a “Y,” and carving into it the date “May 9.” After the war, he kept it on his mantle, “a reminder of the cold-blooded manner in which our gallant commander was killed.” Four hours after Sedgwick’s death, Frederick T. Dent, Grant’s brother-in-law and military aide, plucked a violet from the general’s death site and saved it in a book.

At Meade’s headquarters, Sedgwick’s remains lay on a bier below a bower of evergreens. Before the transportation of the corpse to Washington for embalming, soldiers paid their respects. (There were no reports of a private surreptitiously snipping hairs from Sedgwick’s beard.)

Then, as now, crassness plagued the nation’s capital.

After the embalming at Thomas Holmes’ establishment on Pennsylvania Avenue, the general’s body was visited by a “large number of persons,” the Washington Evening Star reported. At least one of them was a souvenir hunter. Apparently ignoring a guard of four soldiers near the corpse, a woman “exhibited a singular pertinacity to procure a memento of the fallen hero by clipping two buttons from his coat.”

Thieves looted the body of one of the Confederacy’s most beloved generals, too. At about dawn on December 1, 1864, the day after the Battle of Franklin, a search party discovered Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s body near Fountain Carter’s cotton gin, vortex of the bloody fight in which five other Confederate generals fell. The Irish-born Cleburne lay on his back “as if asleep,” his kepi partially covering his eyes. The 36-year-old division commander wore a new, gray uniform and a white, linen shirt stained with blood.

“He was in his sock feet, his boots having been stolen,” recalled a witness years later. “His watch, sword belt and other valuables were all gone, his body having been robbed during the night.” Cleburne had fallen within Confederate lines.

Early in the 20th century, the .36-caliber Colt revolver Cleburne carried at Franklin turned up with a man in Cleburne, Texas. Then it went missing for years. In 1944, it was found by two boys on the banks of the Nolan River in Texas. Today the weapon is in the collection of the Layland Museum in Cleburne.

Perhaps no fallen Civil War general suffered as ignominious a fate as “Old Zolly,” however. Days after the Battle of Mill Springs, a newspaper correspondent spotted Zollicoffer’s body in front of the tent of a sutler, wrapped in a blanket. His skin was “beautifully white and clear,” the reporter noted, and his face had a “pleasant expression,” which “grim in death was not altogether destroyed.” Zollicoffer had shaved off his beard, “probably in order to be less easily recognized,” the correspondent speculated.

But Federals had stripped “Old Zolly” of his clothes, from the white, rubber coat over his uniform to his shirt, undershirt, and socks. An Ohio private snipped three buttons from his coat. Colonel Speed Fry claimed to have Zollicoffer’s spyglass and elaborately engraved sword, apparently bent when the fatally wounded general fell from his horse. (The sword was returned to the Zollicoffer family, according to an 1893 account in The National Tribune, a veterans’ newspaper. In 2020, the weapon and general’s sash from the battle sold at auction for $31,980.)

Another soldier sent a piece of the general’s bloody undershirt to a friend in Alexandria, Va. “The possession of it made me nervous for awhile,” abolitionist Julia Wilbur wrote in her diary. “It is a singular & interesting memento of the Rebellion.” Even Zollicoffer’s hair was cut off close to the skull, apparently by fiendish souvenirs hunters.

“I am sorry to say that his remains were outrageously treated by the thousands of soldiers and citizens that flocked to see them,” wrote the newspaper correspondent, probably exaggerating the number of ghouls.

“On Tuesday evening the body was almost naked,” he added. “This kind of curiosity-hunting borders on vandalism.”

Some vehemently denied the ill-treatment of Zollicoffer’s remains, but the evidence is irrefutable. “I have a small piece of Zollicoffer’s undershirt,” a Federal soldier bragged, “and a daguerreotype of a secession lady, taken with a lot of other plunder.” An Ohio newspaper reported a Union officer showing off a piece of the general’s buckskin shirt: “It was very soft, and must have been exceedingly comfortable if kept dry.”

A week after the battle, 31st Ohio Captain John W. Free wrote of the division of Zollicoffer’s clothes as trophies—“until orders were imperatively given not to do so any more.”

“But his pants and the fine buckskin shirt is no doubt scatered [sic] all over the different States of the North,” the officer added, “as some 4 or 5 different states were here represented.”

Another Ohioan echoed Free’s account. “When the soldiers saw Zollicoffer’s corpse,” wrote Private John Boss of the 9th Ohio, “they tore his clothing from his body, and split up his shirt, in order to have a souvenir. A Tennessean wanted his whole scalp but was prevented from that because a guard was placed there.”

In a letter to a friend, 9th Ohio quartermaster sergeant Joseph Graeff wrote of Zollicoffer: “Inclosed you will find a lock of his hair and a piece cut from his pantaloons. Shortly after the battle I hunted for his corpse, and found it lying in the mud.”

Union Army authorities eventually stopped this macabre nonsense, washed Zollicoffer’s mud-spattered body, and placed it in a tent under guard. “Having no clothing suitable in which to dress him,” a witness recalled, “he was wrapped in a nice-new blanket until they could be procured, after which he was dressed and provided for in a handsome manner….Particular regard and unusual respect were shown his body by officers and men.”

Chaplain Lemuel F. Drake of the 31st Ohio viewed the general’s remains on a board in the tent. “I saw the place where he was shot, and laid my hand upon his broad forehead,” he wrote. “He was about six feet tall, and compactly and well built, one of the finest heads I ever saw.”

The Federals, who kept the body until January 31, considered the general a bizarre (and by then smelly) war trophy. At division headquarters in Louisville, Federal soldiers waited in line for an opportunity to view the remains of the general and his aide, also killed at Mills Springs.

The Union Army embalmed “Old Zolly.” Then “…the bodies of Zollicoffer and his aide were placed in elegant and expensive burial cases by the munificence of the government he had fallen trying to overthrow,” wrote one disgusted Federal soldier.

Under a flag of truce, the two Confederates’ remains were sent through the lines. “It was courteous, soldierly and christian to send to their friends these bodies of men prominent in the bad cause,” wrote the Federal soldier. “But neither courtesy, nor military etiquette, nor Christianity demanded anything more.”

Finally back in his native Tennessee, the remains of one of Nashville’s leading citizens were treated reverently. In early February, Zollicoffer’s body arrived in the state capital, where, despite rainy, “exceedingly disagreeable weather,” thousands filed past the remains at the State Capitol. The next day, the procession to Zollicoffer’s gravesite at Nashville City Cemetery, a little more than a mile away, was “one of the largest ever seen” in the city.

At last, “Old Zolly” could rest.

John Banks, a frequent America’s Civil War contributor, writes from Nashville, Tenn.