In late February 1847, nearly a year into the Mexican War, Gen. José Heredia stood atop a 60-foot escarpment overlooking the Sacramento River. A 1,200-man U.S. force was moving south through the Mexican state of Chihuahua, and Heredia believed he’d found the perfect place to halt the invaders. To advance, the Americans would have to climb the escarpment along a single track. Heredia deployed artillery and built defensive positions to cover the trail, confident his 2,200 men could easily defend the natural fortress.

Eight months earlier the Americans had left Fort Leavenworth, Kan., in company with Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny’s 1,700-man Army of the West, charged with seizing the Mexican territories of Nuevo México and Alta California. The force comprised both Regular troops and assorted volunteer regiments, including nearly 1,000 men of the ragtag Missouri Mounted Volunteers, under Col. Alexander Doniphan. A lawyer with no combat experience, the colonel was nevertheless a natural leader and had earned his soldiers’ respect.

After the Americans captured Santa Fe in August 1846 without firing a shot the column diverged. Kearny took the Regulars west to conquer California, while Doniphan’s volunteers went toward Chihuahua, 500 miles south. The colonel had his first major engagement with the enemy just north of El Paso on Christmas Day. Though Mexican dragoons surprised the column, Doniphan’s Missouri marksmen repelled the assault, and the Americans occupied the town. Doniphan left El Paso on Feb. 8, 1847, with 924 soldiers and 315 wagons driven by teamsters and merchants. Determined to turn a liability into an asset, he organized the civilians into an armed battalion, adding some 300 weapons to his strength.

On February 27 Doniphan’s column made camp some 15 miles north of Chihuahua. Having learned from El Paso, Doniphan sent out scouts and gained intelligence on enemy positions along the river. The scouts also identified an alternate route up to the plateau—one not covered by Heredia’s extensive defenses.

The next day Doniphan approached as the Mexicans expected. What they didn’t expect was the formation he used. The colonel had formed his wagons into four parallel columns about 30 feet apart, intermingling his infantry and artillery within the moving box and placing 200 mounted men out front.

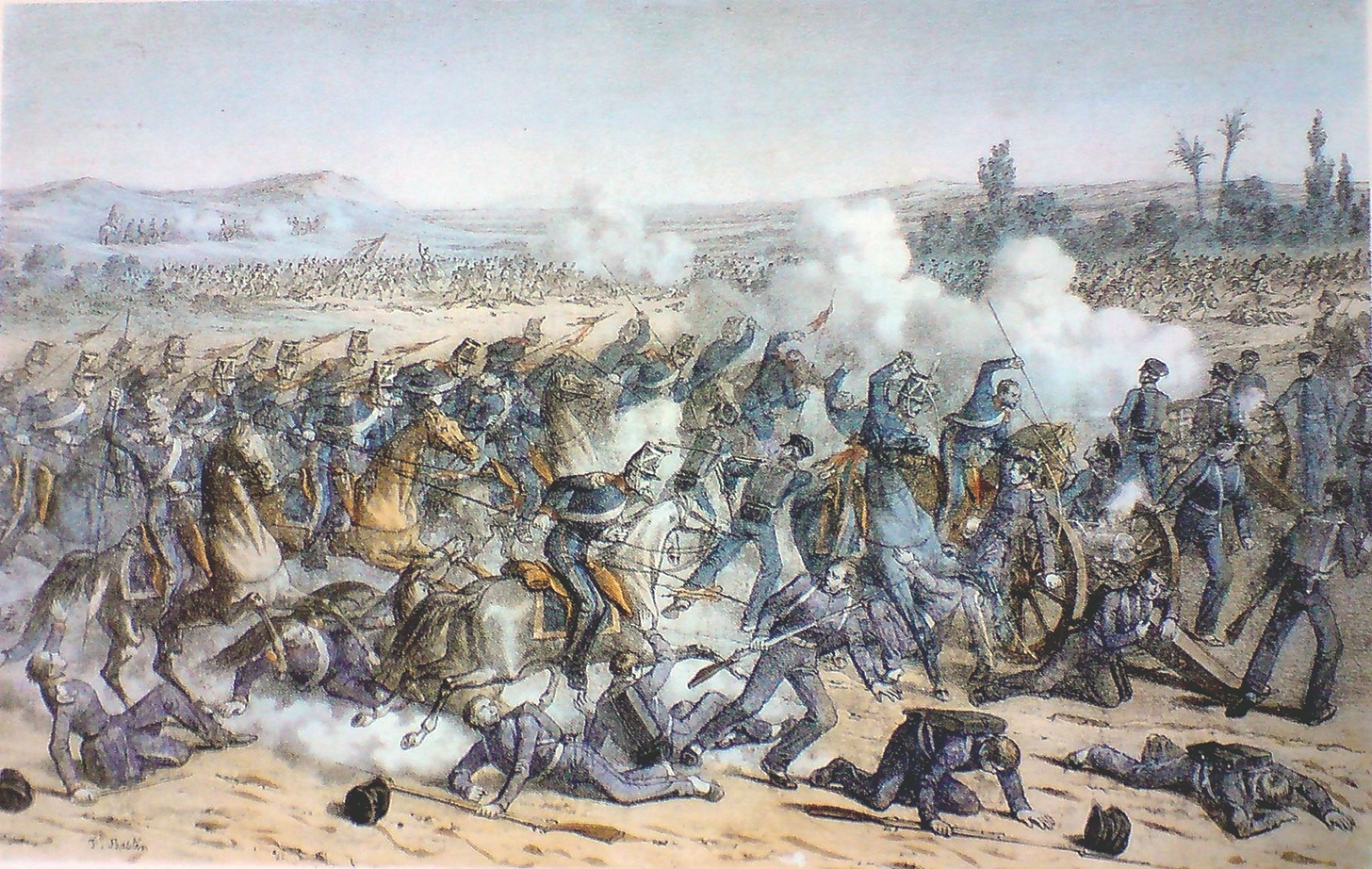

The second shock to the Mexicans came when Doniphan’s caravan crossed a gulch thought impassable and rumbled up onto the plateau from the west, leaving Heredia’s defensive positions facing the wrong way. The general unleashed more than 1,000 lancers and cavalrymen, the lead rider holding aloft a skull and crossbones flag—signifying no prisoners would be taken. The Mexican riders charged into the waiting American artillery, whose accurate, massed volleys broke the charge, sending the horsemen into retreat. As Heredia tried to rally his men, Doniphan’s force swept across the plateau, shattering the Mexican army.

Described by historian Winston Groom as “one of the most lopsided victories in U.S. military history,” the Battle of the Sacramento claimed more than 700 Mexican casualties at the cost of four Americans killed and eight wounded. Left on the field by the retreating Mexicans was the black flag of no quarter, which today hangs in the library of the Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis.

Lessons:

Look before you leap. Skillful American scouting won the battle before it was fought.

Wagons, ho! Doniphan turned his merchant wagon train into a combat multiplier.

Be ready to improvise. Doniphan’s unorthodox tactics kept the enemy from responding effectively.

Combined arms provide a winning edge. Heredia’s unsupported cavalry charges against infantry and artillery failed completely, leaving hundreds dead.