In September 1861, while stationed in Paducah, Ky., Private John H. Page of the 1st Illinois Light Artillery received notice that he had been promoted to second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Infantry and was to report for duty in Washington, D.C. After packing his belongings, Page caught a boat for Cairo, Ill., where he reported to the general in charge of the District of Southeast Missouri before obtaining transportation for the next leg of his journey.

Page immediately recognized Ulysses S. Grant perched behind a wire screen at a local bank where the general had set up his headquarters. “He looked at my commission and seemed buried in deep thought,” Page recalled. “He looked at me intently and repeated several times, Jno. Page,” apparently lost in reverie. It took a tap on the shoulder by a gray-haired officer in attendance to snap Grant out of his trance.

Assuredly, Grant had been reminiscing about the Mexican War, Page suspected, when he, then a 24-year-old second lieutenant, personally witnessed a Mexican cannonball mortally wound Page’s father, Captain John Page Sr., during the fierce Battle of Palo Alto. “No doubt,” Page concluded in observing Grant’s unusual reaction, “his thoughts, when looking at my commission were wandering back to his early days.”

Grant and Private Page had both lost something special during the U.S. victory at Palo Alto on May 8, 1846: Page ultimately his father, and Grant his innocence.

We, of course, will never know for sure what crossed Grant’s mind when the young private handed him his commission, but the now 39-year-old brigadier had perhaps revisited the senior Page’s disfiguring wound, him writhing in agony on the plains of Palo Alto…the comrade he had lost 15 years earlier.

For many of the more than 500 Mexican War veterans who became Confederate or Union generals during the Civil War, battle deaths evoked strong emotional reactions. Those traumatic experiences had introduced them to the dreadful lessons of war: that it was terrible, that loss and grief were normal, and how to cope with them. Inevitably, death in battle played a significant role in shaping their identities.

Dr. Nigel C. Hunt, who studies war trauma and memory, stresses that most individuals who go through such ordeals react with intense memories or emotions when recalling what they witnessed, although that doesn’t necessarily mean they will suffer from long-term or debilitating problems. Even with these memories indelibly etched into their minds, most continue to live normal lives. Grant and his comrades never forget what they saw or how they felt when confronted with death on the battlefield in Mexico.

“I cannot feel exultation”

Mexican War battles were bloody affairs, especially for U.S. Army officers. They made up 8 percent of the war’s battle deaths, which surpassed the mortality rate of other U.S. 19th-century conflicts. Renowned historian James M. McPherson says that in the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War, the proportion of officers killed in action was about 15 percent higher than that of enlisted men. During the Mexican War, the proportion of officers killed in action or who died of their wounds was more than 40 percent higher than the rank and file.

During Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott’s 1847 Mexico City Campaign, for instance, his army lost 61 officers killed to roughly 703 soldiers (8 percent). In comparison, during the Seven Days’ Battles in 1862, the Army of Northern Virginia lost 175 officers killed to 3,494 soldiers (5 percent). If the losses sustained among Confederate officers during the spring and summer of 1862 were staggering, as Dr. Joseph T. Glatthaar suggests, the mortality rate among Scott’s officers in Mexico was catastrophic.

Major Edmund Kirby, who lost many dear friends and cherished companions, including his nephew, during Scott’s campaign, wrote to his wife, Eliza: “Blood. Blood. Blood. Enough has been shed to excite the worst enthusiastic joy throughout our dear country. Enough to cause tears to flow sufficient to float a ship of war.”

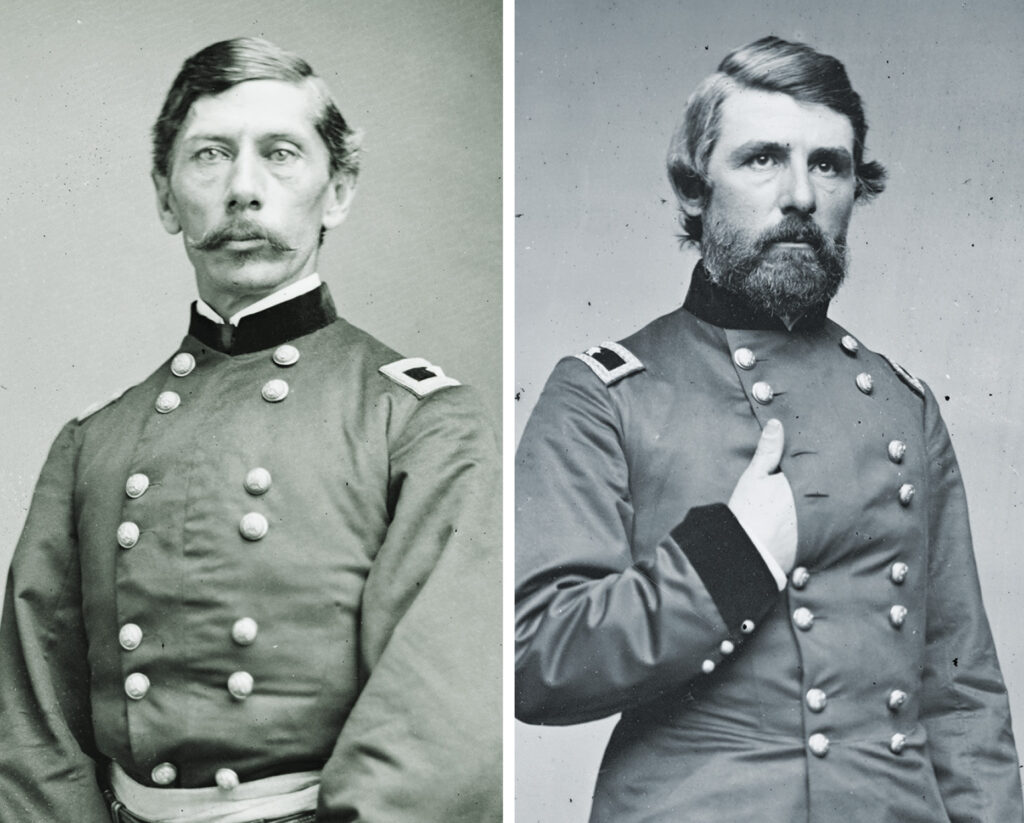

The Mexican War was an emotionally taxing experience for its soldiers, especially its officers, who witnessed a disturbing proportion of their comrades die in battle. When Scott’s army seized Mexico City, 1st Lt. John Sedgwick wrote his sister, Olive, that “were it not for the loss of so many near and dear friends,—friends with whom we have enjoyed all the pleasures of a long peace, and with whom we have shoulder to shoulder encountered and vanquished the enemy…our situation would be pleasant.”

Captain Isaac I. Stevens, also with Scott’s army, told his wife, Margaret, that while he was alive and healthy, he could hardly celebrate. “I cannot feel exultation,” he admitted. “We have lost many brave officers and men, some my personal friends; streams of blood have in reality flowed over the battlefield.” Both generals were later killed while serving in the Union Army during the rebellion—Sedgwick at the Wilderness in May 1864, and Stevens at Chantilly (Ox Hill) in September 1862.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

After the August 1847 Battle of Contreras, Captain Robert E. Lee, eventually the Confederacy’s most famous general, best captured the emotional distress it caused many when he declared: “It is the living for whom we should mourn, and not the dead.”

Studies that address Civil War generals and their role in the Mexican War typically concentrate on the military lessons they took away from their service and how they applied them on Civil War battlefields. That is important, but what is often overlooked is the emotional impact the war, especially battle deaths, had on them during the short but costly struggle. The sickening sights on battlefields or in hospitals, and the sudden and violent loss of comrades, friends, or relatives, evoked a flood of intense emotions such as grief, horror, shock, melancholy, guilt, loneliness, helplessness, and numbness. The deeper the bond with the deceased individual, the more emotionally impactful the loss. To better understand the individuals who fought in Mexico before the Civil War, we must begin to look beyond the war as merely a “training ground” or a jovial gathering of friends-turned-enemies and recognize the emotional impact battlefield deaths had on them.

Distress and Detachment

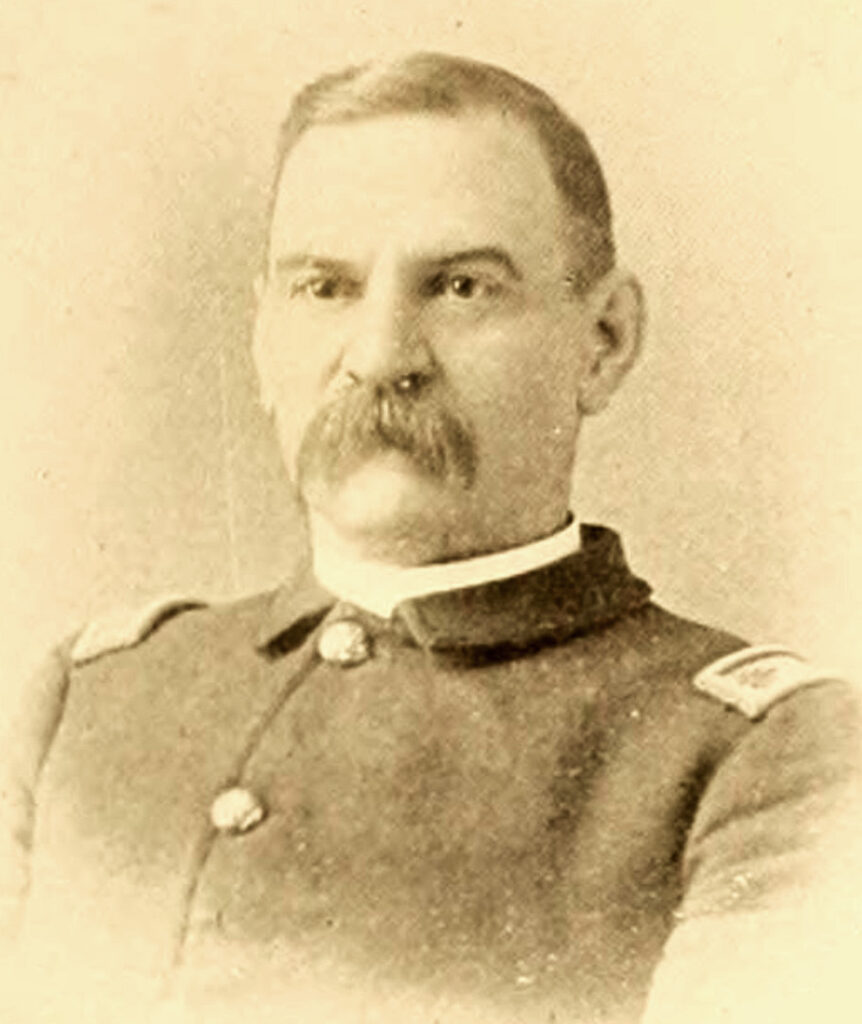

Second Lieutenant Henry M. Judah, a Union brigadier general who commanded a division during the 1864 Atlanta Campaign, found it unsettling to recollect to his mother, Mary, what he had experienced at the Battle of Monterrey in September 1846.

“Their cries and groans, the terrible hissing of the cannon and musket balls, which filled the air, added to the roar of artillery in every direction, made an impression that I could never describe,” he wrote to her three days after Brig. Gen. Zachary Taylor’s army captured the city.

During the battle, several musket balls had grazed his cheeks, and had his sword knocked from his hand by a cannonball. An 1843 West Point classmate and fellow lieutenant fell dead mere feet away from him. Dazed and dirtied, Judah hunkered down behind a mound of earth as a shower of artillery and musket fire passed just feet above his head. “[E]very face looked blank—all were exhausted—and the wounded and the dead were mixed with the living,” he recalled.

When Mexican soldiers began to advance on their position, a feeling of indifference overtook the young lieutenant. The emotional callousness alarmed him more than anything else he felt that day. “My feelings at this moment were more horrible than those of death,” he admitted to his mother. “I began to feel reckless, and cared not how soon it came.”

Within only a short period, Judah experienced a surge of fear, excitement, anxiety, horror, dread, and detachment.

The emotional highs and lows of combat, as Judah experienced, can be overwhelming for a soldier, but the battle’s aftermath can be equally—and arguably more so—distressing emotionally.

The first two battles fought during the Mexican War, on May 8-9, 1846, left both fields littered with death and destruction. Mutilated men and horses, abandoned wagons, discarded weapons, and everything of which an army is composed carpeted the landscapes at Palo Alto and, the following day, Resaca de la Palma. Steel, lead, and iron inflicted horrific wounds—mangling limbs, crushing heads, and severing bodies and trunks. Most Civil War generals who fought at these two battles were exposed to the butchery of war for the first time in their lives.

“Such a field of carnage never was before witnessed by any of us,” 1st Lt. William H.T. Brooks, who commanded a 6th Corps division during the Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville campaigns of 1862-63, wrote home after the battle.

Second Lieutenant John J. Peck, who for a time during the Civil War commanded all Union troops in Virginia south of the James River, told his father that while the two armies battled at Resaca de la Palma, the American soldiers paid little attention to the dead Mexican soldiers. “[B]ut after the excitement of battle has passed away,” he admitted, “our sympathies were aroused, and I felt keenly all the horrors of war.”

Judah, who provided his mother with a vivid account of his Monterrey ordeal, admitted that the mutilated bodies on the Resaca battlefield were a terrible vision. He couldn’t find the words to describe the horror.

A day later, he remained haunted by the experience, writing her: “The cries of the wounded still ring in my ears.”

Processing Trauma

Battlefield death left a lasting impression on the survivors. “I was somewhat affected by the sight,” said 1st Lt. Charles S. Hamilton, later a Union major general, after coming upon the mangled bodies of Mexican soldiers killed at Monterrey, “but ere the night of that day had closed I learned to look upon the dead with as little emotion as I would regard a stone.”

Consciously or subconsciously, Hamilton was using repression as a defensive mechanism. According to Dr. Dillon J. Carroll, who studied and wrote about mental illness during the Civil War, soldiers used emotional desensitization or “hardening” to cope with death—as did Mexican War soldiers.

In his memoirs, Hamilton confessed the sight of those dead Mexican soldiers at Monterrey “affected me more than any other scene during the entire war.”

When Hamilton arrived at Bishop’s Palace the morning after the battle, he witnessed additional horror, later providing a graphic account. He watched a Mexican soldier struck by a shell that had burst and obliterated him as it passed through his body. “If you imagine a human being ground by two avalanches crushing him between them,” Hamilton would write, “you would have a similar sight.”

The other soldier had been hit in the forehead by a musket ball. His brain oozed from a hole in the back of his head and dried foam clung to his lips as he had taken his last gasping breaths. “Enough of these descriptions,” Hamilton would note. “[Y]ou will little like them, while I have become callous to the most ghastly sights.”

Dr. Carol Acton, who has studied wartime grief, says that, for soldiers, writing about a traumatic experience offers them the means to express and cope with emotional distress and grief. Conceding that his loved ones might wince at his graphic descriptions, Hamilton shared what he saw and felt anyway, likely as a way to process the trauma.

Returning to a particular battlefield often triggered emotions many years later. Lew Wallace, a second lieutenant in Mexico who would hold important Civil War commands at both Shiloh (1862) and Monocacy (1864), said that, despite all his subsequent experiences in war, one section of the Buena Vista battlefield was the most horrible after-battle scene he had witnessed. “The dead lay in the pent space body on body, a blending and interlacement of parts of men as defiant of the imagination as of the pen,” the future author of the famed novel Ben-Hur would write.

Wallace made three pilgrimages to the Buena Vista battlefield over a seven-year-period. On one of his visits, he noticed a Mexican farmer with a hoe casually digging a path in the dirt and leading a stream of water to irrigate a wheatfield. It was the same field he had described above. Wallace wondered if the healthy-looking wheat had been nurtured by the blood of the American soldiers struck down there in February 1847.

Eternal Camaraderie

It is one thing for a soldier to observe the death of another with whom he had no intimate relationship than to watch a mentor, messmate, or close friend die in combat. The emotional bond formed among soldiers is distinct, as they suffer and face dangers together, risk their lives for one another, and rely on each other for emotional support and survival.

For many of the U.S. Army’s junior officers who served in the Mexican War, they had spent years together before the conflict, as West Point classmates or for long periods at isolated frontier outposts. When a comrade was killed in battle, this eternal camaraderie understandably brought forth intense emotions comparable to the loss of a family member.

Ulysses Grant became familiar with shattered friendships and loss in Mexico. Even though Palo Alto was Grant’s first battle, it was not the fear of death that most affected him, but the sight of a colleague (especially a friend) suffering a horrific wound.

For Grant, that had been “the ghastly hideousness of his visage” as Captain John Page, his face shot away by an enemy cannonball, “reared in convulsive agony from the grass.” As he wrote his friend John W. Lowe about Captain Page’s disfiguring wound: “The under jaw is gone to the wind pipe and the tongue hangs down upon the throat.”

In his memoirs, written nearly 40 years later, Grant relived the detail of that enemy cannonball that had decapitated one soldier and then mutilated Page, splattering nearby American soldiers with brain matter and bone fragments.

Page was the first of many of Grant’s comrades killed during the war, but he was the closest with 2nd Lt. Robert Hazlitt, a fellow Ohioan and graduate of West Point’s Class of 1843, one of 18 U.S. officers killed or mortally wounded at Monterrey. Hazlitt regularly accompanied Grant on his visits to the White Haven Plantation near St. Louis when he began courting Julia Dent.

Grant tended to internalize his emotions, but, having lost so many friends at Monterrey, finally broke down. “How very lonesome it is here with us now,” he wrote to Julia a month after the battle. “I have just been walking through camp and how many faces that were dear to the most of us are missing now.”

Three other lieutenants in the regiment had been struck down storming the city besides Hazlitt, and remained constantly on Grant’s mind: Charles Hoskins, Richard H. Graham, and James S. Woods.

Was Grant experiencing bereavement overload, survivor’s guilt, or both? To drive away “the Blues,” Grant retrieved some old letters and a journal he kept while stationed at Jefferson Barracks, Mo., and reminisced about happier times.

Grant expressed his close friendship with Hazlitt in a November letter to Hazlitt’s brother, James, assuring him that only his dear friend’s family could feel his death more deeply. Monterrey, Grant wrote, “will be remembered by all here present as one of the most melancholy of their lives.”

As Grant’s fame grew during the Civil War, he used his influence to assist the relatives of one of the officers he mourned in 1846. In late 1863, Charles Hoskins’ widow, Jennie, wrote to Grant from New Rochelle, N.Y., imploring him to help her 17-year-old son, John Deane Charles Hoskins, secure an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy. Grant had lent the boy’s father his horse shortly before he was killed at Monterrey.

In January 1864, Grant had Illinois Rep. Elihu B. Washburne deliver a note to President Abraham Lincoln asking him to appoint the boy to West Point. On a military telegraph approving Hoskins’ appointment, Lincoln scribbled the words “Gen. Grant’s boy” next to the cadet’s name. A month after Grant was appointed to the rank of lieutenant general, Jennie Hoskins wrote him reporting that her son had received the appointment. (He would graduate in 1868, serve for 40 years, and retire as a brigadier general.)

Family Bonds

Captain Robert E. Lee’s eyes stayed glued on his older brother, U.S. Navy Lieutenant Sydney Smith Lee, when the American guns opened on the Mexican defenses at Vera Cruz in March 1847. Robert’s brotherly instinct kicked in, and he was determined to shield Sydney from danger, even though there was little he could do to protect him from the enemy’s shells. The thought of Sydney being wounded or killed, however, petrified him. As he would write his wife, Mary, afterward: “[W]hat would I have done had he been cut down before me!”

Fortunately for Lee, he did not have to find out. But there were a handful of other Civil War generals who experienced Lee’s worst fear and more when a blood relative was killed.

Difficult to comprehend perhaps, the subsequent U.S. assault at Molino del Rey would eclipse anything Grant and other U.S. soldiers had experienced at Monterrey. On September 8, 1847, General Scott ordered an attack on a cluster of stone buildings and earthworks to capture a foundry in which he believed the Mexicans were melting church bells to cast cannons. In only two hours, however, Brig. Gen. William Worth lost nearly 25 percent of his force, and 17 U.S. officers were either killed during the battle or would die of their wounds.

When Ethan Allen Hitchcock, acting inspector general to Scott, visited the field after the debacle, he came upon Captain William Chapman of the 5th U.S. Infantry. In a moment jarringly similar to the one Confederate Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett famously had on July 3, 1863, after Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, Chapman pointed to the regiment’s survivors—now reduced roughly to the size of a company—and exclaimed with tears rolling down his face: “There’s the Fifth.”

Among the mortally wounded was Captain Ephraim Kirby Smith of Chapman’s regiment. A musket ball had struck him in the face under the left eye and passed through his head, exiting near the left ear. Smith’s uncle, Major Edmund Kirby, had Ephraim (“Kirby” to family members) taken to his quarters in Tacubaya.

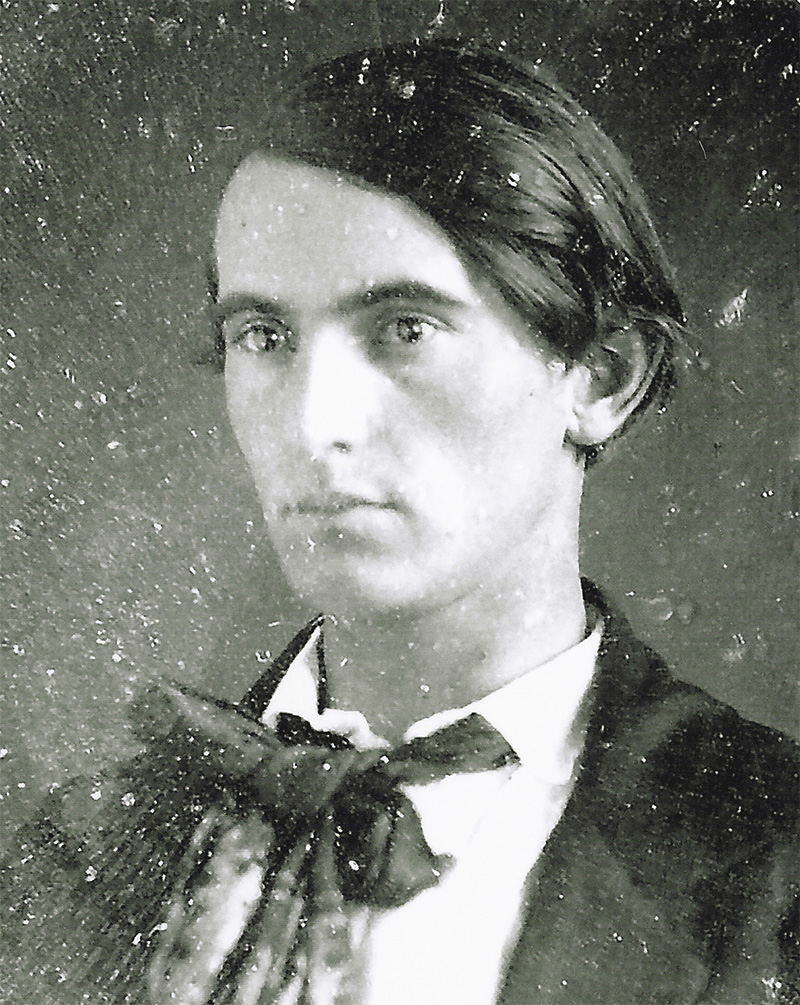

Second Lieutenant Edmund Kirby Smith, the fallen warrior’s brother, would become famous as a Confederate lieutenant general and commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department during the Civil War. Known by family members as “Ted,” he would visit his mortally wounded sibling several times, but when he arrived on September 11 to the hospital where “Kirby” had been moved, Ted learned his brother had died.

Having lost his father, Joseph Lee Smith, in May and now his older brother just four months apart was deeply distressing, and Ted also feared for his brother’s three young children—Joseph, Emma, and George—left to grow up without their father.

The young lieutenant was also pained by his sister-in-law’s financial welfare, as no pension system existed in the Army at the time for soldiers’ widows. How would she and her children cope? Among the eerie thoughts plunging through his anguished mind was that it would have been better had he been killed and not his brother.

“Burned into the Soul”

When Captain John W. Lowe arrived in Mexico City in the spring of 1848, he noted that his friend Ulysses Grant had undergone a transformation, writing to his wife: “[H]e is a short thick man with a beard reaching half way down his waist and I fear he drinks too much but don’t you say a word on that subject.”

While some writers believe that Lowe’s statement was an early indication of Grant’s alcoholism, they overlook what he might really have been trying to convey: that Grant was battling his traumatic war experiences.

The lieutenant had been in Mexico for two years, away from Julia for three, and had participated in nearly all the war’s major battles without an opportunity to take leave. He had witnessed much death and many close friends die. After the death of Sidney Smith, a friend and second lieutenant in the 4th U.S. Infantry, in 1847, he told Julia that out of all the officers that left Jefferson Barracks with the 4th, only three, including himself, remained. In fact, 21 percent of the officers who started the war in Grant’s regiment were killed or died of their wounds, and 11 percent of the 4th’s battle deaths consisted of officers. The high fatality rate among officers in Grant’s regiment led to the nickname “the Bloody 4th.”

In 1884, the year before Grant died of throat cancer, The Salt Lake Tribune reported that Grant retained vivid recollections of his pre-Civil War years: “[T]he Mexican War seems more distinct to him than the Rebellion,” the newspaper declared, and also maintained that the war’s battles were “burned into the soul of Grant as with a brand of fire.”

In his memoirs, Grant claimed that he greatly benefited from the “many practical lessons it taught,” but he omitted his more private experiences. As he was hesitant to openly express his inner feelings, particularly when he expected them to be published and shared with the public, it is not surprising Grant decided to omit the grief and loneliness he had experienced with the death of comrades in Mexico. Those emotions, however, are evident in his private letters.

Grant wasn’t alone in expressing this inner turmoil. Many Mexican War veterans who became Civil War generals likewise expressed their deepest feelings in private journals, letters home, and postwar memoirs. Certainly, both Union and Confederate generals gained valuable military experience in Mexico that they would apply in the Civil War. It is important, however, to recognize that the Mexican War also served as an emotional training ground for these leaders. The deaths they witnessed taught them harsh lessons about the realities of war, triggered powerful emotional responses, and left a lasting impact on their character and values long before the Civil War.

Frank Jastrzembski, a regular America’s Civil War contributor, writes from Hartford, Wis.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of America’s Civil War magazine.