As an unattached young man, John Wilmot was clearly stirred by the extraordinary patriotic fervor circulating in the summer of 1861. A little time would show that he had also been stirred by something more common.

News of the Union disaster at the First Battle of Bull Run reached Vermont’s Connecticut River Valley in the midst of haying season. Barely a week after the battle, Governor Erastus Fairbanks decided to raise two new regiments of volunteers, although most conceded that recruiting would lag while the crucial hay crop was being cut. The customary pay for farm hands in the area seldom exceeded $1 a day, but they could demand $1.50 or more per day from the middle of July until mid-August, when the last load had been collected. Army pay of $13 a month paled by comparison, even after considering the $7 monthly bonus the state had authorized for all the enlisted men in Vermont regiments.

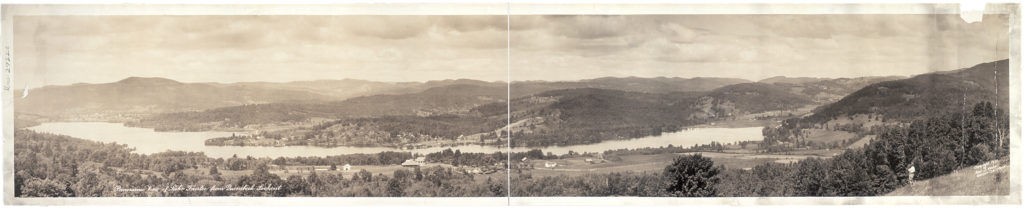

Nineteen-year-old John Wilmot would have taken full advantage of that premium pay. He had been supporting himself for at least a couple of years, boarding and working at a farm near his childhood home in the village of Post Mills. Good weather continued through the second week of August 1861, but by then most farmers had their hay collected, and Wilmot had to choose between resuming life as a regular hand or indulging the exciting prospect of going to war. Army pay and the Vermont supplement would give him the same $20 a month he might earn at farm labor, but the federal government also promised a $100 bounty at the end of a three-year enlistment.

There was nothing to keep him in Vermont’s Orange County. His mother was long dead, his father had just remarried twice in merely four years, and there was no family farm for him to tend or inherit. He also had no close relationship with any member of the opposite sex, although he had been introduced to the ways of the flesh, apparently only recently. Sometime during that 1861 haying season, he had enjoyed the company of Sophronia Ann Prescott, a domestic for a nearby family who was several years his senior. She clearly didn’t mean enough to him to figure in his plans when he decided to enlist.

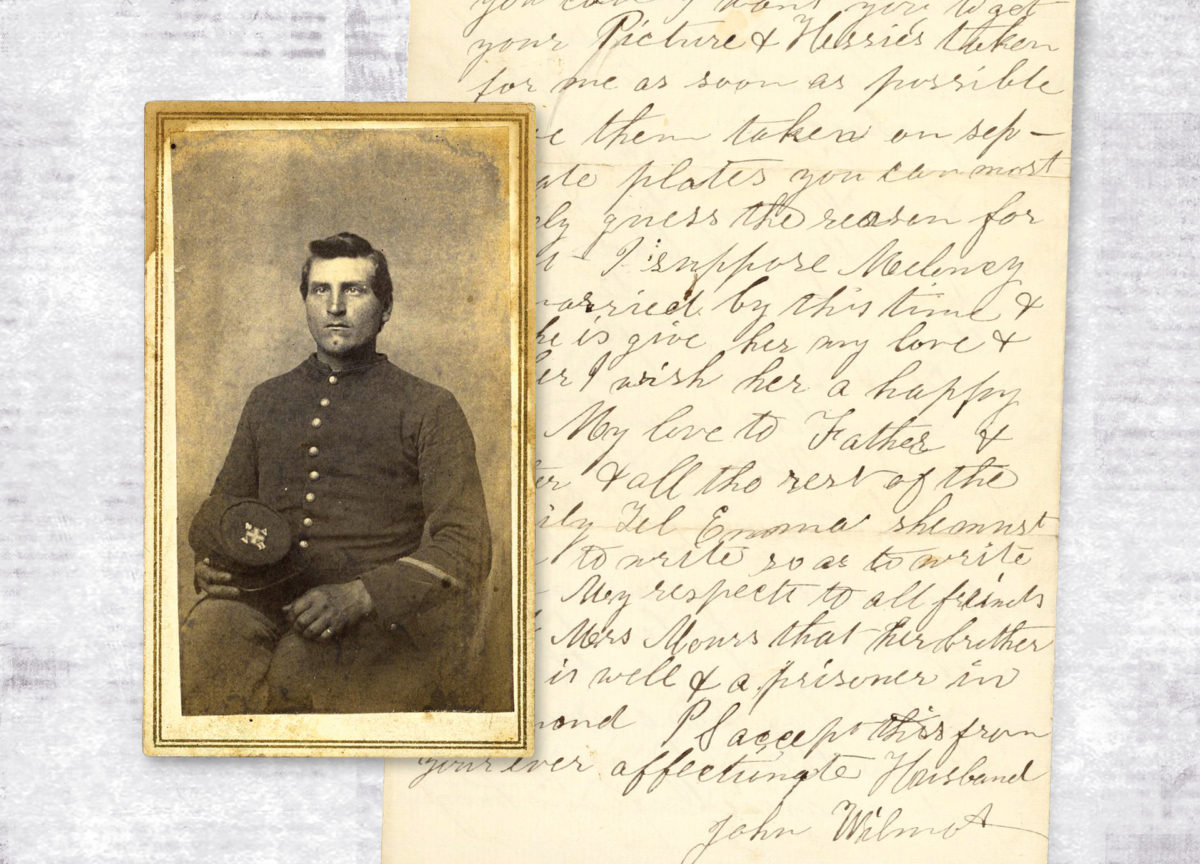

On September 9, Wilmot signed the roll of what was soon mustered in as Company H, 4th Vermont Volunteers, and he arrived with that regiment in Washington, D.C., on September 23. After a couple of weeks around the U.S. Capitol, the 4th Vermont moved across the Potomac River to Camp Griffin, joining four other regiments from the Green Mountain State to form the Vermont Brigade. It remained there until spring.

A Child’s Arrival

It was a bad winter for the Vermonters, whose sick list exceeded that of any other brigade in the Army of the Potomac. Measles raced through the camps, as well as typhoid and remittent fever, and by January nearly a quarter of the 4th Vermont was under the surgeon’s care. Two men in Company H died that winter, and five more returned home with disability discharges. Wilmot was sent to the hospital for several weeks himself. When he emerged at the end of February, he believed he was frail enough to merit a discharge, yet he declined to apply for one, fearing it might disqualify him for the $100 federal bounty.

By then he was in touch with Sophronia, who apprised him that she was pregnant. His first letter in reply does not survive, but internal evidence suggests that their correspondence had not been extensive when he wrote the second one, on March 5, 1862. There is no evidence of any understanding between them, or of any communication from her until she informed him of her condition. Their intimacy appears to have been altogether casual—quite possibly a solitary encounter—but young John either assumed that the child was his or accepted Sophronia’s assertion that it was.

The two of them had been raised in villages separated by only a few miles, on either side of Lake Fairlee, but in an age of pedestrian travel it might as well have been leagues. Otherwise, Wilmot might have understood that chastity apparently didn’t run strong among the Prescott girls. Sophronia’s older sister, whose perennially misspelled first name was probably meant to be Melency, had borne a son out of wedlock barely four years before Sophronia’s liaison with Wilmot. The child Sophronia carried that winter of 1862 would be the first of no fewer than three she would conceive without benefit of matrimony. It would not be the last illegitimate child she credited to John either, although her other children were born years after Wilmot was dead.

Wilmot did not seem to entertain any immediate suspicion over Sophronia’s undisguised pecuniary motivation either. He promised her $20 of the $26 he would be paid at the end of every other month, but she wanted his $7 monthly state bonus as well. He had already given control of that money to his father, who would still be his legal guardian for two more years. His regular pay was another matter, but after he promised to send the bulk of that to Sophronia, he did not hear from her for another six months. When she finally did write, it was apparently to complain about a four-month period in which he had not been mustered for pay and she had not seen any money from him.

During her long silence, Wilmot had endured the entire Peninsula Campaign; he had also taken part in the harried retreat of Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia after the Second Battle of Bull Run in August 1862 and had followed the fortunes of the 6th Corps through the late-summer fighting in Maryland. He wrote to her after the Antietam Campaign, but Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside had taken command of the Army of the Potomac before Wilmot learned that Sophronia and the baby girl she had delivered were alive and well. The child was then nearly seven months old, but Sophronia either failed to name it or to tell Wilmot what name she had chosen. He referred to her as “the baby,” or “the little girl.”

In his long reply to her letter, the young soldier promised to do as well by her as he could, financially. He only asked—in vain—that she write to him weekly. Sophronia’s letters have not been preserved; their frequency and content can be judged only from the evidence in his, but she seems rarely to have written more often than monthly, if that.

After a two-month lapse in the spring of 1863, she insisted that she had written several times, yet Wilmot never received any of those letters. He did not challenge her claim, but so many letters flew in the face of her usual habit, and his situation was not then subject to any of the common causes of lost or delayed mail. He had been with his unit in the same camp all that time, where mail had reached him regularly for four months, including two earlier letters from her, with his customary address.

When she did write, it was to say that she was out of money or to ask when the army was going to be paid. In one letter, she mentioned her father’s annoyance at having to help support her child, prompting Wilmot to promise he would reimburse Mr. Prescott, too, when he came home. Her repeated appeals for more support may have moved him to doubt her ability to manage money, and by the end of 1862 he began directing much of his pay to his schoolteacher brother, Willard, to be saved until he returned. He still sent Sophronia small amounts if she avowed she could not “get along without it,” but no longer did he send her the lion’s share of his income.

Wedding Planning

If any letters passed between them through the brutal summer of 1863, they have been lost, and none are hinted at in the surviving correspondence. Late in September, however, she wrote asking what he planned to do when he made it back to Vermont. With enough diffidence to show that they had never discussed the topic, he replied, “If I live to get home I shal get Married the first thing I do if any one will have me.”

At the age of 21, John Wilmot might have been a hardened veteran of several campaigns, but he was also a motherless boy far from home, ham-handedly proposing marriage to a virtual stranger, as homesick young soldiers were wont to do. He knew so little of her that he seemed uncertain what she preferred to be called, addressing her alternately as Sophronia or Ann, or resorting to the perfectly neutral “My Dear Friend.”

Still living with her parents in her late 20s, with the burden of an illegitimate child, it seems probable that Miss Prescott did not hesitate long before suggesting herself as a prospective bride for his hypothetical marriage. Her acquiescence can also be inferred from his next letter, 12 weeks later, in which he sought her opinion on a significant life decision. The War Department had begun offering substantial inducements for reenlistment, hoping to retain the veterans whose terms would end the following spring and summer, and on December 19, 1863, Wilmot asked Sophronia what he should do.

The federal government was paying a $300 bounty to all recruits by December 1863, and 1861 volunteers such as Wilmot were already owed their original $100 enlistment bonuses. On top of that, the War Department added another $100 bounty for any veteran who reenlisted, along with the $2 recruiting bounty traditionally paid to anyone who persuaded someone else to enlist.

Vermont also offered a $125 bounty to any soldier enlisting under that state’s draft quota. That would give him $627, besides whatever bounty voters decided to offer in the town of Thetford, which encompassed Post Mills. Vermont town bounties were then fluctuating between $200 and $600, with most communities settling on $300. About a third of that money would come in cash, with the rest distributed over the course of the reenlistment period. Wilmot would also have accumulated $189 in state subsidies by then, so if he enlisted again he would be worth well over $1,000 at a time when most laborers still earned only $300 a year. With the state bonus, he would also realize an additional $240 a year in pay.

After tallying all the benefits for Sophronia, Wilmot added one more slightly cryptic inducement: “I forgot to tel you too[,] all that reenlist are granted a furlow of thirty days. Let me know in your next what you think I had better do.”

She had not been asked to approve of Wilmot’s first decision to enlist, and likely was not even aware of it before he departed. His reenlistment would yield abundant ready cash with periodic replenishment, and if they were married those funds would allow her to live independently of her parents, to whom she had been compelled to return late in her pregnancy. Even if Wilmot were killed, all the bounty money would accrue to his widow, if he had one, as would a small pension.

The news of the promised furlough—with the implied opportunity for them to be married—may have been the deciding factor for her, as Wilmot seemed to intend. She surely gave her assent, but he must have assumed that she would, for he had already reenlisted four days before he wrote to her.

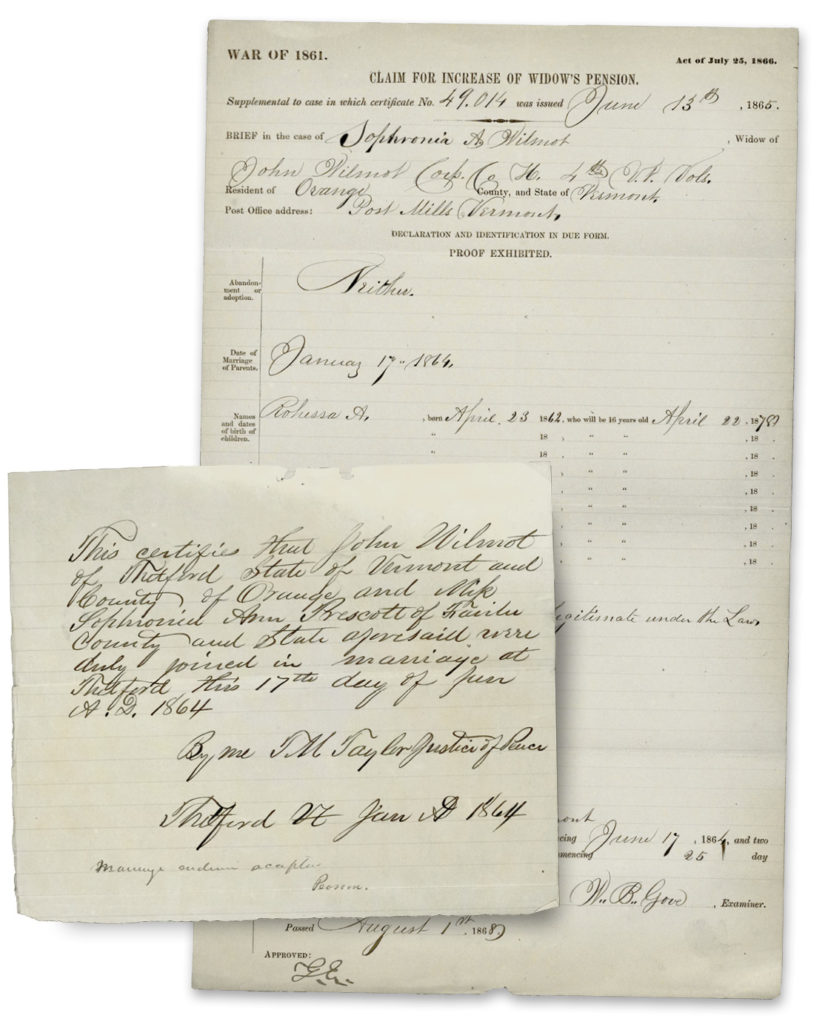

Wilmot came home after the first of the year, and on January 17, 1864, Thetford’s local justice of the peace united him and Sophronia in marriage. It was a busy season for the Prescott girls, and Melency also snared a husband, exchanging vows six weeks later with a former comrade of Wilmot’s in Company H who was a decade her junior.

After establishing Sophronia in housekeeping in her own lodgings in Post Mills, Wilmot returned in February to his regiment’s camp at Brandy Station, Va. At last he began to call the baby by name, shortening Rohessie Ardell Wilmot to “Hessie.” He assured Sophronia that he was “the happiest man that ever lived,” but he also betrayed lingering apprehension at taking a wife he barely knew, adding, “I hope I shall never have occasion to regret my choice.”

Wounded in the Wilderness

Wilmot would have no time to regret his decision, or to know Sophronia better. On May 4, the Vermont Brigade crossed the Rapidan River at Germanna Ford, and the next afternoon it ran head-on into Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s Division in the Wilderness, near the Brock Road’s intersection with the Orange Plank Road. Under the most furious fusillade the brigade faced during the war, some 1,200 Vermonters fell dead or wounded, including a score of men in the 4th Vermont’s Company H. Wilmot, freshly promoted to corporal, lay among them with a bullet in his left leg.

Transported to Fredericksburg by ambulance and then to Washington by steamer, he landed finally at Mower General Hospital in Chestnut Hill, Pa. The bullet was removed weeks later, but he had a history of wounds that healed stubbornly, and he grew so weak that a bout of fever carried him off on June 17. He had turned 22 by the time he died.

As soon as she learned that John was dead, Sophronia gave her case to a local claims agent, who collected all the paperwork she needed to obtain a widow’s pension of $8 a month. That was easy enough, and by the following spring, pension checks began arriving in Post Mills. An additional $4 monthly allowance for her daughter proved more difficult, because the child’s birth predated her mother’s marriage long enough that pension examiners questioned whether Wilmot was indeed the father. Wilmot’s letters appear to have been saved precisely because they provided evidence that he had accepted Hessie as his own, and after several years of wrangling with the Pension Bureau, Sophronia won the additional stipend.

By then the widow had already had at least one liaison with another man, becoming pregnant only weeks after she began collecting her pension. A few days before the second anniversary of Wilmot’s death, she gave birth to another girl, whose father she did not name, but that child died less than four months later. Hessie was 4 years old at the time and ought to have retained some memory of a baby sister, but Sophronia omitted the dead daughter from all renditions of her family history thereafter.

Had Sophronia remarried, she would have had to relinquish her pension, which may account for her avoidance of marriage, but she clearly did not avoid men. Ten years after John Wilmot died, she conceived yet again, bearing a son named Alger Wilmot in early 1875. He lived until 1936, whereupon his death certificate revealed the family myth that John Wilmot had also been his father. Sophronia was probably the author of that deception, but it was a much later contrivance.

While her son still lived with her, she concocted another fiction to explain Alger’s birth, presenting herself as having been divorced from a nonexistent second husband. Periodic relocation provided her with new communities in which to reinvent her past, and after her son left home, she moved to the quarry town of Barre with Hessie and her son-in-law, resuming the role of widow. There she died in late 1909, having drawn her pension without interruption for more than 45 years.

For Love or Money?

As tempting as it is to gild John Wilmot’s experience with Sophronia Prescott as the saga of a young man living up to his responsibilities, it would be reasonable to wonder whether the responsibility was actually his. After all, the Prescott sisters clearly pursued carnal encounters more readily than was common among their contemporaries, who generally strove to address unexpected pregnancies with hasty nuptials. Moreover, Sophronia—whose birthdate is calculated as August of either 1837 or 1838—was as much as five years older than John, and she had long been living on her own when they shared their fateful moment together. That moment did not reflect a romantic relationship, and there is a distinct possibility that he was not her only partner that summer, although she may well have been his first.

In 1861, a single woman who found herself in a family way in Orange County faced limited economic options. What industrial work the region offered was available only to men, and if women lacked either education or reputation, the role of schoolteacher was closed to them. Domestic work in a respectable family was usually out of the question for an unmarried mother. Her only hope lay in the man, or men, whose passions she had indulged within the radius of a month or so. For Sophronia Prescott, John Wilmot had either been that man or one of the men. If he was not the sole candidate, he was young and gullible, and he enjoyed the steady income of Army pay and the generous Vermont supplement, on which many of the state’s soldiers supported entire families.

Money appeared to be Sophronia’s primary concern, too. Considering how persistently she demanded cash support, her failure to even mention marriage in nearly two years demonstrates that personal regard and affection played little or no part in their physical interaction. She may have accepted enthusiastically enough when he finally introduced the subject, but by then the alliance would afford her considerable financial benefits. Becoming Wilmot’s wife gave her a modest lifetime income, which she never jeopardized by marrying the other men who impregnated her.

The behavior that Sophronia modeled had its effect on the next generation. Rohessie Wilmot was still 16 years old when she gave birth to her own first child, barely five months after an expedited wedding, but as Hessie Lathrop she enjoyed a much more stable life than her mother had known. Conceived about the time of the First Bull Run disaster, she lived until the 99th anniversary of that battle. Public interest in the approaching Civil War centennial may have been what saved her mother’s collection of letters from the furnace.

William Marvel, who writes from South Conway, N.H., is the author of Radical Sacrifice: The Rise and Ruin of Fitz John Porter (UNC Press, 2021). His next book is tentatively titled Rebel Resurrection: Ten Weeks That Revived the Confederacy.