On the first day of the Allied offensive on the Somme River of northern France in July 1916 the British suffered 57,470 battle casualties, making it the bloodiest single day in that nation’s military history. Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, realized he must change tactics. Thus, he gave orders that all the newfangled tanks that had reached the Western Front be employed in a subsequent assault on German-held French villages dubbed the Battle of Flers-Courcelette. A dozen Allied infantry divisions and all 49 available tanks attacked the German front line that September 15. The tanks psychologically shattered the Germans, instilling in them a fear they termed “Panzer Angst” and prompting many to flee. Those who held their ground found that their most potent weapons—artillery shrapnel and machine guns—were useless against the lumbering armored beasts. In the first three days of fighting the British captured more than a mile of German-held territory.

Thanks for the British success was due in part to an unlikely early proponent of armored mechanized warfare—Winston Churchill.

That summer Churchill’s service as commander of the 6th Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers had come to an end. He’d been serving on the Western Front for the past six months after having taken a break from politics. The reason for that break was his undeniable link to the disastrous Gallipoli campaign in Turkey. As first lord of the Admiralty, Churchill had been among the chief advocates for opening another front in the Dardanelles. In the wake of the sub-

sequent military fiasco, Churchill temporarily left politics and resumed his previous commission as a British army officer. What he witnessed in the trenches refocused his attention on a technological innovation he’d championed in the Admiralty—an armored vehicle that could break the stalemate on the Western Front.

Winston Churchill’s service to Great Britain as a cigar-chomping, no-nonsense prime minister during World War II has been the subject of countless books, articles and films. Less well known is his service as a British army officer after his graduation from the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. As a young cavalry officer he saw active duty in the far reaches of the empire, including Cuba, India and the Sudan. After having served some five years, he resigned his commission to pursue politics and was elected a member of Parliament in the House of Commons. While Churchill served primarily as a politician for the rest of his life, he never abandoned his interest or involvement in military matters.

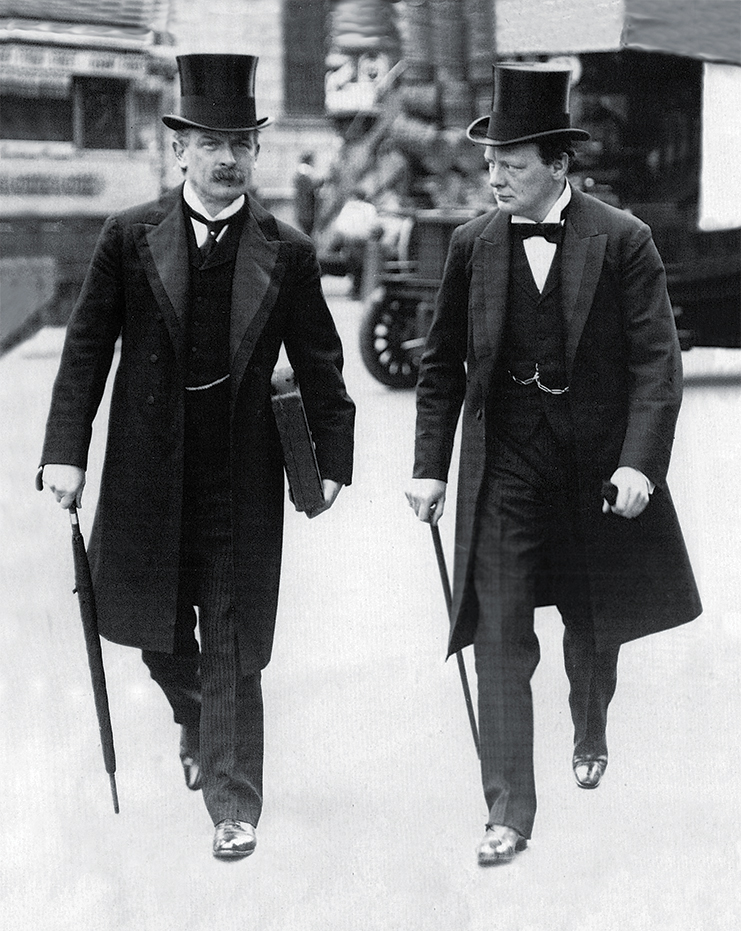

In 1911, after a decade in public office, Churchill was appointed first lord of the Admiralty by Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith. Winston had always expressed a keen interest in naval matters, as a member of Parliament often pushing for increases in defense spending for the Royal Navy. As first lord he pushed for higher pay for naval staff, ramped up production of submarines and beefed up the nascent Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). Churchill encouraged the navy to determine how aircraft might be used for military purposes, coined the term “seaplane” amid debate in the House of Commons and ordered 100 of the latter for naval use. His advancements were timely. Three years into his appointment as first lord Britain entered World War I.

With the onset of war Churchill grew increasingly obsessed with the Middle Eastern theater. Hoping to relieve Ottoman pressure on Allied Russia in the Caucasus, he proposed a combined naval expedition against Turkish gun emplacements in the Dardanelles. Churchill hoped a successful outcome there might enable the Allies to seize the Ottoman capital of Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), force Turkey out of the war and allow British naval forces to transit the Bosporus Strait into the Black Sea. Churchill anticipated that Romania, a neutral nation bordering the Black Sea that harbored hostility for its Austro-Hungarian neighbor, would ultimately allow Allied troops to use its territory to open a southern front against Germany and Austria-Hungary.

Allied representatives signed off on Churchill’s ambitious plan, and in February 1915 an Anglo-French fleet dubbed the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force sailed to commence a naval bombardment of Turkish defenses in the Dardanelles. On March 18 the Allied fleet, comprising 18 battleships and an assortment of cruisers and destroyers, launched its main attack against Turkish defenses at the narrowest point of the Dardanelles, where the straits between Asia and Europe are only a mile wide. The British first ordered civilian-crewed minesweepers into the straits, which soon retreated under significant artillery fire from Ottoman shore emplacements, leaving the minefields largely intact. At the outset of the attack the French battleship Bouvet struck a mine, capsized and sank within minutes; just 75 of its crew of more than 700 survived. The British battlecruiser Inflexible and pre-dreadnought battleship Irresistible also struck mines. Inflexible was severely damaged and compelled to withdraw. Irresistible was lost, though most of its crew was rescued. Sent to Irresistible’s aid, the battleship Ocean was damaged by shellfire and then struck a mine, sinking soon after its crew abandoned ship. Also damaged by shellfire, the French battleships Suffren and Gaulois had to withdraw. With his combined fleet bloodied, Rear Adm. John de Robeck, the British commander, ordered a withdrawal.

Churchill and others in favor of opening a southern front remained determined. If the Turkish emplacements could not be silenced by naval gunfire, then a ground invasion of the Gallipoli peninsula would serve the purpose. The planned assault called for Allied forces to conduct amphibious landings and then attack the Ottoman forts from the landward side. Initiated on April 25, the landings targeted several beaches on the peninsula. The Allied assault was conducted primarily by British and Commonwealth soldiers, including Australian and New Zealand troops, but also included a French contingent.

Organized on short notice, the amphibious assault suffered from a dearth of intelligence regarding enemy defenses and lacked accurate maps. Seeking to overcome both shortfalls, planners turned to seaplanes from No. 3 Squadron of Churchill’s vaunted RNAS. Unopposed by the small Ottoman air force during the preparation phase, the squadron initially provided aerial reconnaissance. Once the invasion was under way, the planes conducted photographic reconnaissance, observed naval gunfire and reported on Turkish troop movements. The squadron also conducted a handful of bombing raids in support of Allied ground troops.

One handicap Allied planners were unable to overcome was the fact Ottoman forces held the high ground in the interior beyond the beachheads. The Turks knew their own geography and had modern artillery and machine guns provided by their German allies. The campaign devolved into a stalemate, with the Allies unable to break out from the beachheads, and the Turks unable to overrun them. A rare Allied highlight of the campaign was that Churchill’s Royal Navy was able to interdict most enemy merchant shipping seeking to resupply Ottoman forces in Gallipoli. That alone might have ultimately forced Turkey to sue for peace. But the Allied situation at Gallipoli soon devolved after Bulgaria joined the Central Powers. In early October 1915 the latter opened a land route through Bulgaria, connecting Germany and the Ottoman empire and enabling the Germans to rearm the Turks with modern heavy artillery capable of devastating the Allied positions. Germany also supplied Turkey with the latest aircraft and experienced crews.

‘Darth’ Tanker

Actually harking back in appearance to medieval Japanese samurai armor, this 1916-issue leather British tanker’s helmet with mask was designed to protect its wearer from head injury. When leather proved too flimsy, British tankers switched back to the steel Brodie helmet.

Seeing no realistic way to turn the situation to their favor, the British Cabinet made the difficult decision to evacuate in early December 1915. While Churchill hadn’t been the sole proponent of the disastrous campaign, he’d been among its most vocal, thus many ministers of Parliament held him personally responsible. The following May the prime minister agreed under parliamentary pressure to form an all-party coalition government on the condition Churchill be removed from his Cabinet position.

Unceremoniously booted from his appointment as first lord of the Admiralty, Churchill took a break from politics and resumed frontline service as an army officer. In January 1916 he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and given command of the 6th Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers. After training, the battalion deployed to a sector of the Belgian front. For more than three months they experienced continual shelling and sniping while preparing to meet the expected German spring offensive. As the Germans were focused on taking Verdun, Churchill’s sector remained relatively quiet. In May the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers were absorbed into the 15th Division. Churchill didn’t seek a new command in the division, instead securing permission to leave active duty and return to politics. But his military contributions were far from over, and the seeds of an earlier endeavor were about to bear fruit.

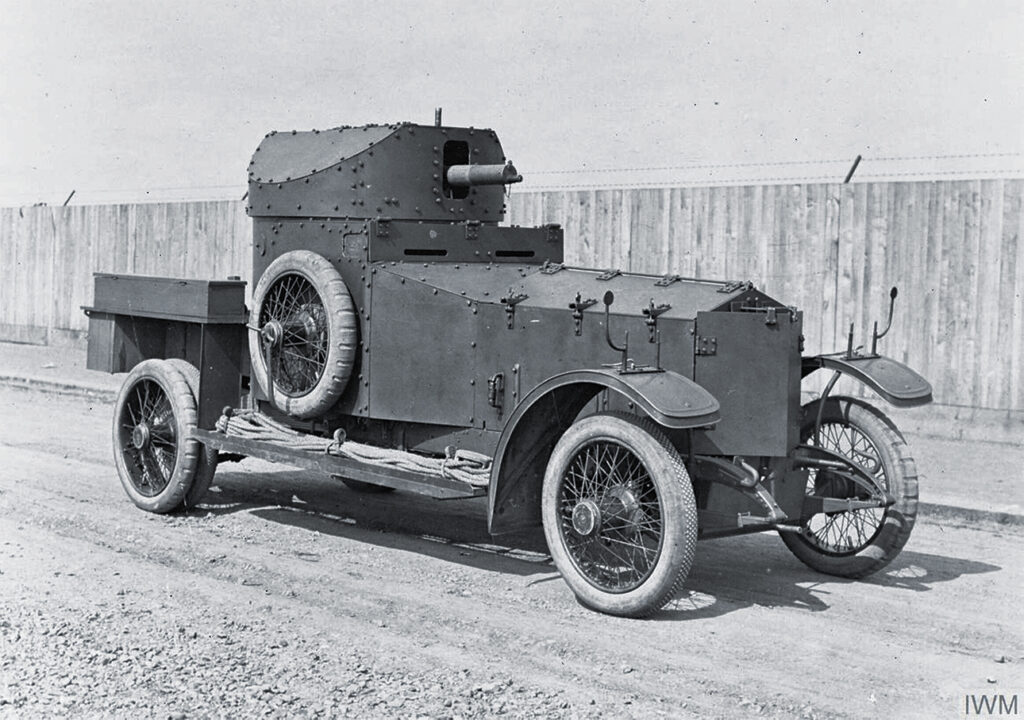

In 1914, when the war slipped into stalemated trench warfare, First Lord Churchill had fished about for solutions and came to believe an armored motorized vehicle of some sort was the answer. Seeking ownership of the technology on behalf of the Admiralty, he’d labeled such futuristic armored vehicles “landships.” Eventually conceding the technology was more appropriately an army initiative, Churchill transferred £70,000 (more than $8 million in today’s dollars) from the navy to the army to develop what became known as the tank.

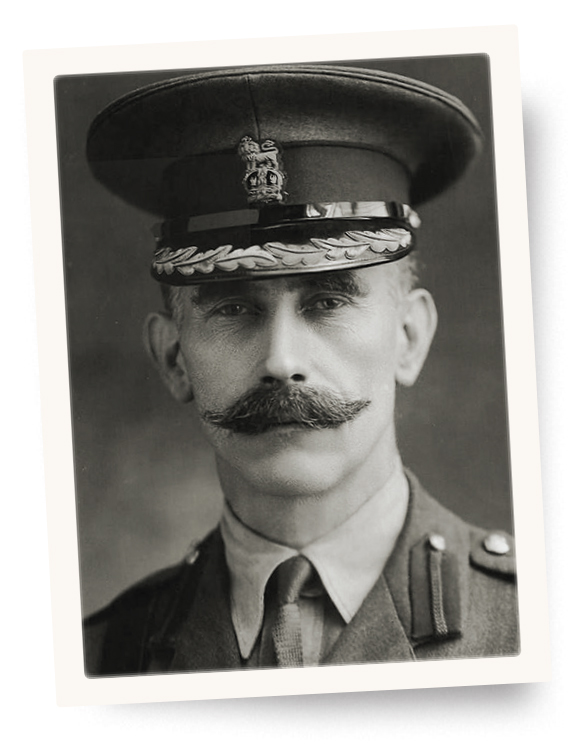

The man most often credited with having invented the tank is Lt. Col. Ernest D. Swinton. Appointed at the outset of the war by Secretary of State for War Horatio Herbert, 1st Earl Kitchener, as the official British war correspondent on the Western Front, Swinton moved back and forth between France and England and to and from the front lines. Witnessing the death, destruction and deadlock of trench warfare, he initially conceived an armored variant of the American-made Holt caterpillar tractor. While Kitchener proved lukewarm over Swinton’s armored tractor, it resonated with First Lord of the Admiralty Churchill, who in February 1915 ordered formation of an exploratory Landship Committee, tasked with developing the technology.

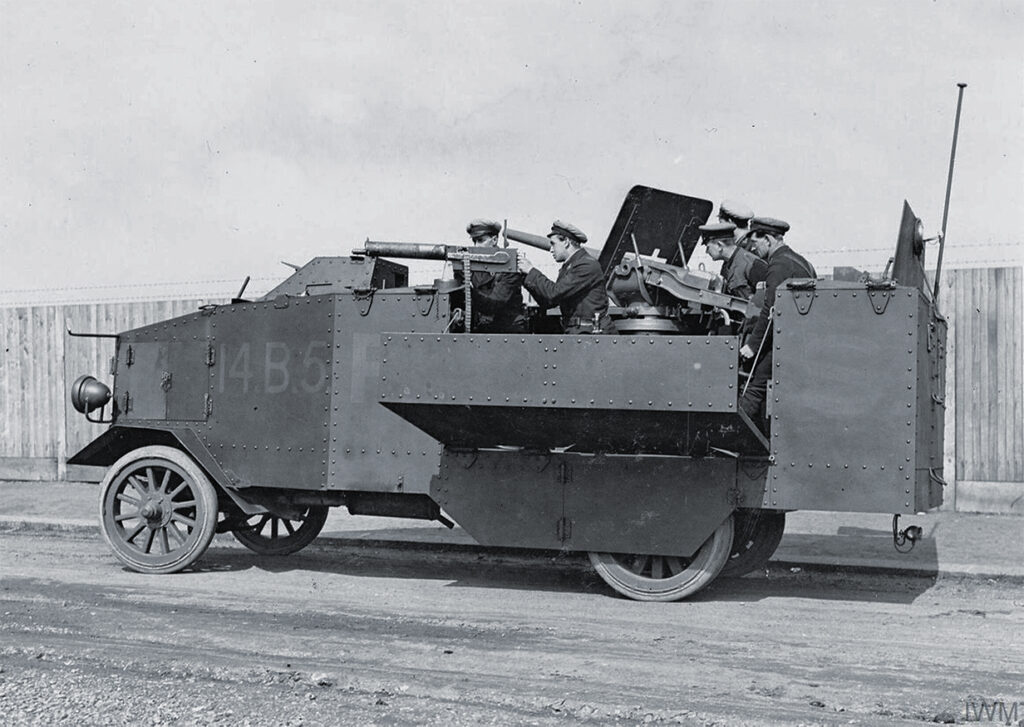

Under Churchill’s ministry oversight were naval air squadrons based in Dunkirk, France. Perpetually at risk of enemy attack, the squadrons were ably defended by armored car squadrons. Thus, Churchill recognized the importance of and need for armored forces. He kept abreast of developments as the Landship Committee experimented with armored vehicle designs. The initial versions were essentially wheeled automobiles with bolted-on armor. However, it soon became clear wheeled variants could neither traverse trenches nor function properly in mud. Churchill’s Admiralty experimented with attaching bridging equipment to such vehicles, but the results proved disappointing. Swinton’s Holt caterpillar tractor proved far more promising. Offering greater grip and more weight-bearing surface, the tracked vehicle was just the ticket for crossing the no-man’s-land between trenches.

On June 30, 1915, Churchill arranged a demonstration of a prototype tractor’s ability to cross barbed-wire entanglements. A manufacturing company working on the project eventually produced the Killen-Strait armored tractor. Capped with the superstructure from a Delaunay-Belleville armored car, its tracks comprised an unbroken series of steel links connected by steel pinions. Churchill and David Lloyd George, then head of the Ministry of Munitions, were present for tests of the Killen-Strait. The promising results prompted Lloyd George to assume the responsibility for producing a steady supply of landships once the Royal Navy settled on a satisfactory design. For his part, Churchill was a total believer, convinced the new machine would enable Allied forces to readily traverse the muddy, shell-pocked landscape of the Western Front and smash enemy defenses.

Meanwhile, Swinton managed to persuade the newly formed Inventions Committee in the House of Commons to fund development of a small landship. He drew up target specifications for the new machine, including a maximum speed of 4 miles per hour on flat ground, the ability to perform a sharp turn at top speed, reversing capability, the ability to climb a 5-foot earthen bank and the ability to cross an 8-foot gap. Additionally, the vehicle was to accommodate 10 crewmen and be armed with two machine guns and a 2-pounder cannon. Though the landship was no longer under the purview of the Admiralty, Churchill went out of his way to write Asquith in praise of Swinton’s developments.

Under Swinton’s oversight, the prototype landship, nicknamed “Little Willie” had 12-foot-long track frames, weighed 16 tons and could carry a crew of three at a top speed of just over 2 miles per hour. Its speed over rough terrain, however, dropped considerably. Moreover, it was unable to traverse trenches more than a few feet wide. But while the initial trials proved disappointing, Swinton remained convinced a modified version would prove a breakthrough weapon.

Its manufacturers immediately began work on an improved tank. The resulting Mark I, nicknamed “Mother,” was twice as long as “Little Willie,” keeping the center of gravity low and helping its treads grip the ground. Sponsons were fitted to the sides to accommodate two 6-pounder naval guns. During initial trials in January 1916 the tank crossed a 9-foot-wide trench with a parapet more than 6 feet high.

With that, Swinton decided it was time to demonstrate the new tank to Britain’s leading political and military figures. Thus, on February 2, under conditions of utmost secrecy, Secretary of State for War Kitchener, Minister of Munitions Lloyd George and Chancellor of the Exchequer Reginald McKenna gathered with other key personnel to see the Mark I in action. Lord Kitchener remained unimpressed and skeptical of the tank’s potential contribution toward victory. Fortunately for the Allies, Lloyd George and McKenna, the two with oversight of the government purse strings, did recognize the Mark I’s potential and by April had placed orders for 150 tanks. Churchill was ecstatic.

Foreshadowing the German Wehrmacht’s Blitzkrieg tactics, Churchill believed the army should wait to field the Mark I until factories had rolled out 1,000 tanks and then employ the shock value of a combined armor assault to win a great battle. Though Field Marshal Haig harbored doubts about the value of tanks, the British Expeditionary Force commander did order all available Mark Is to assist during that summer’s Somme Offensive. Unfortunately for their advocates, many of the tanks broke down, and the British army was unable to hold on to its gains.

Truth be told, the tank’s debut was not as great a success as the British press reported it to be. Of the 59 tanks that had arrived in France, only 49 were in good working order. Of those, 17 broke down en route to their line of departure for the attack. It must be noted that Swinton had cautioned commanders to carefully choose fighting ground that corresponded with the tank’s powers and limitations. Had they followed his recommendations, the initial results would have been better. Regardless, the sight of the tanks created panic and had a profound effect on the morale of the German army.

For his part, Colonel John Frederick Charles “J.F.C.” Fuller, chief of the British Heavy Branch of the Machine Gun Corps (later Tank Corps), was convinced his machines could win the war and persuaded Haig to ask the government for another 1,000 tanks. Churchill, who by then had returned home as a politician, did everything he could to endorse Haig’s request.

Meanwhile, Fuller and others refined tank operating procedures, and just over a year later, during the Cambrai Offensive, Haig ordered a massed tank attack at Artois. Launched at dawn on Nov. 20, 1917, without preparatory bombardment, the attack wholly surprised the Germans. Employing more than 400 tanks, elements of the British Third Army gained up to 5 miles that first day, an incredible amount of territory to be captured so rapidly on the stalemated Western Front. Churchill’s belief in the tank as a combat multiplier had been validated. The British army remembered his tireless efforts, and at the outset of World War II it named its primary infantry tank, the Mk IV, the Churchill.

Retired U.S. Marine Colonel John Miles writes and lectures on a range of historical topics. For further reading he recommends Thoughts and Adventures, by Winston S. Churchill; A Company of Tanks, by William Henry Lowe Watson; and Eyewitness and the Origin of the Tanks, by Ernest D. Swinton.

This story appeared in the Autumn 2023 issue of Military History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.