In today’s world of satellites, cell phones and routine transatlantic flights, it may be hard to understand the impact 25-year-old Charles Lindbergh made when he flew his single-engine Spirit of St. Louis nonstop from New York to Paris in May 1927. By the time he touched down at Le Bourget airport, 33½ hours after he took off from Long Island’s Roosevelt Field, Lindbergh was the most famous man in the world.

The instant adulation didn’t come because Lindbergh was the first person to fly across the Atlantic — that had been accomplished eight years earlier, when a U.S. Navy seaplane made the trip, which took 19 days and required multiple stops. The “Lone Eagle” wasn’t the first to fly nonstop across the Atlantic, either. English officers John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown had flown without stopping from Newfoundland to Ireland in 1919. Lindbergh was, however, the first to fly nonstop between New York and Paris, winning a race to capture a $25,000 prize put up by hotelier Raymond Orteig. Several other, better-known, aviators had also been vying for the prize, and some of them had died trying. The previous September, famed French World War I ace René Fonck had crashed while trying to take off from Roosevelt Field; two of his crew died. Two other Frenchmen, Charles Nungesser and François Coli, had attempted to fly from Paris to New York just days before Lindbergh’s attempt but disappeared along the way.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Even more than what Lindbergh had done, how he had done it captured the world’s imagination. Lindbergh was a young, unknown airmail pilot flying a plane built by an obscure San Diego company. He did have financial backers, but the Lone Eagle made the flight solo — a quintessential plucky American going it alone against great odds. His story galvanized the world. When the Spirit of St. Louis appeared in the skies above Paris on the night of May 21, more than 150,000 people were waiting at Le Bourget, delirious with excitement. They mobbed the field when he landed, tore pieces of fabric from his airplane, and overwhelmed the pilot, who was hustled into a car by some helpful Frenchmen and sheltered in a hangar until he could be safely transported to the American embassy.

Upon Lindbergh’s return to the United States, more than 4 million people gave him a rapturous welcome in a New York City ticker-tape parade that left 2,000 tons of confetti littering the city’s streets. Everyone was mad for Lindy. People wrote songs and poems about him, and they danced the Lindy Hop. Movie producers vied to sign him up; manufacturers of everything from fountain pens to breakfast cereal wanted the Lindbergh name on their products. “One of the salesmen of the Thompson Manufacturing Company in Belfast, Maine, realized they could move their breeches faster if they started calling it the ‘Lindy’ pant,” wrote biographer Scott Berg. That salesman was hardly the first or the last person to capitalize on Lindbergh’s fame.

Observers marveled at the figure at the center of this maelstrom. He seemed like such a nice young man — quiet, polite, modest. He was everything an all-American hero was supposed to be, and America embraced him passionately, fervently, and feverishly.

A Nice Young Man Comes to Portland

Shortly after his return home, Lindbergh decided he would use his new stature to awaken America to the potential of air travel. He accepted a proposal from the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics to fly his famous airplane to every state in the Union and preach the gospel of commercial aviation. He planned to depart on July 20 from Long Island and head north to New England, with his first stop in Hartford, Connecticut. His schedule had him reaching Portland, Maine, on Saturday, July 23.

Portland had a brand-new airport — so new it hadn’t officially opened yet — just outside the city in Scarborough (or Scarboro, as the Portland Press Herald spelled it). Lindbergh expected to land there at 2:45 Saturday afternoon. “Every precaution humanly possible will be taken at the Portland Airport at Scarboro to make Lindbergh’s arrival not only safe and convenient for the pilot, but an event which can be witnessed in comfort by the maximum number of visitors,” the Press Herald told its readers.

Recommended for you

The Portland Chamber of Commerce issued a warning that the aviator would turn back to Boston if Portland residents rushed the field, as Parisians had done at Le Bourget. Once on the ground, Lindbergh would be whisked into a waiting car and driven into the city, escorted by motorcyclists of the Maine State Police.

The parade route was planned to avoid as many trolley tracks as possible to prevent the Lone Eagle from being jostled. A guard of honor, consisting of an infantry company, a Marine detachment, sailors from the USS Seatle, three batteries of artillery from the Maine National Guard and 1,000 “citizen soldiers” from Fort McKinley Citizens’ Military Training Camp planned to display their drill routines for Lindbergh. If they had enough time, they also planned a display of “mass calisthenics.”

After the parade, Lindbergh was scheduled to address the gathered hordes in a field at Deering Oaks at 3:45 p.m. The reception committee prepared for a crowd of 30,000 people. Lester C. Ayer of the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company set up a public address system to ensure that everyone in the crowd would be able to hear. The committee also made arrangements to park an “extraordinary number of automobiles free of charge.” Following his address, Lindbergh would return to the Eastland Hotel in Portland in preparation for a dinner there that evening. All 700 tickets were sold out by Thursday.

Philip J. Deering, the head of the reception committee, asked that everyone in Portland who owned American flags display them during Lindbergh’s visit. The fire department planned to blow its whistles to announce the aviator’s arrival. “When Colonel Lindbergh arrives, he will discover at first hand that New England restraint itself has limits which yield to feats of importance equal to his flight across the lonely Atlantic,” the Portland paper said.

Evasive celebrity

Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis began the tour as scheduled. He was accompanied by a second plane, provided by the U.S. Department of Commerce and piloted by Phil Love, an old friend of Lindbergh’s from his days as an airmail pilot. Serving as Lindbergh’s aide was Donald Keyhoe, who worked for the commerce department. The only other member of the team was mechanic Ted Sorenson. At Hartford, 50,000 people turned out to see the Lone Eagle. “A slender fair-haired young fellow who appeared to be just out of his ’teens, rolled and slipped and dived his way into the hearts of 50,000 usually staid, Connecticut citizens at Brainard Field today,” reported the Associated Press.

Lindbergh stopped in Providence, Rhode Island, on Thursday and reached Boston on Friday, leading to the death of one man from “over-excitement” in the delirious horde at the airport. During Lindbergh’s appearance on Boston Common, members of the National Guard “rescued 17 women who had been knocked down and trampled by the surging crowd,” according to an AP report. Lindbergh, the Press Herald said, spent his day at “the center of a howling mob of devotees who made any sacrifice of their personal safety for one glimpse of their hero.” Maine’s Governor Ralph Brewster was in Boston to greet Lindbergh but had to miss the Portland appearance so he could attend a governor’s conference in Michigan.

At one of the first stops, Lindbergh demonstrated his single-mindedness — as well as his growing dislike of the press — when a reporter tried to get him to talk about his private life.

“Is it true, Colonel, that girls don’t interest you at all?” she asked.

“If you can show me what that has to do with aviation, I’ll be glad to answer you,” Lindbergh said.

“Then aviation is your only interest?”

“That is the purpose of this tour, to promote aviation.”

“Are you always so evasive?” the reporter asked.

“I shall be glad to tell you everything I know — on aviation,” Lindbergh answered.

As Lindbergh made his way north, Portland braced for impact. In a boxed item on Saturday’s front page simply headlined “Please!” the Press Herald implored people to keep off the airfield until Lindbergh had landed and repeated the aviator’s request that no other pilots attempt to rendezvous with him in the air.

Waiting for Lindy

The sun rose on Saturday behind a thick bank of clouds and fog. In Scarborough, contractors had been working feverishly to get the new airfield ready. In Portland, thousands eagerly anticipated sighting the famous aviator. “Maine turns its eyes to the Western sky today to catch the first glint of silvered wings, for the hearts of the people are impatient to welcome and honor Charles Augustus Lindbergh, the modest representative of American youth who thrilled the world with his spirit and made his countrymen proud of their birthright,” said the Press Herald. “One thought is uppermost in every mind. Men, women and children have determined to show the young aviator the admiration they feel for his courage, skill and daring. They seem to chafe under the restraint of their New England nature, lest he fail to understand the warmth in their hearts for his unperishable gallantry in the face of odds.”

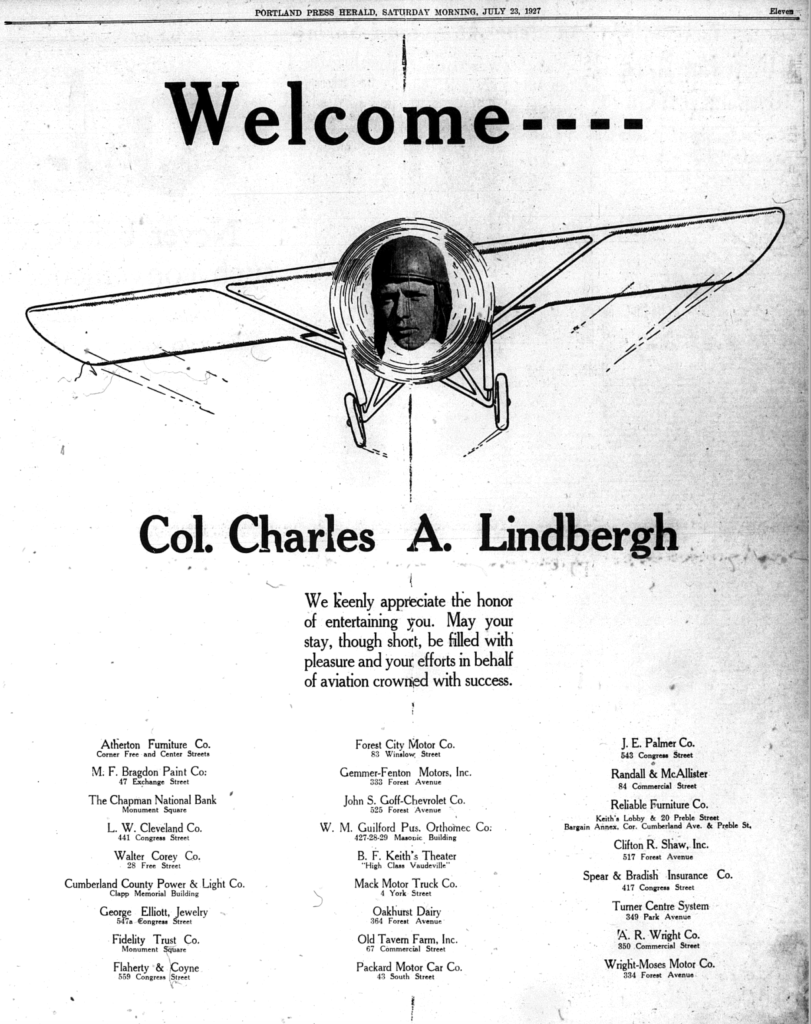

Local businesses trumpeted their admiration for Lindy. The department store Loring, Short & Harmon at Monument Square took out an ad to promote the impending arrival of “We,” Lindbergh’s book about his flight, priced at $2.50 and due “to be published shortly, probably late this month.” Chapman’s, at 245 Middle Street, took out an ad to welcome Lindbergh and to tout its “large assortment of white felt hats and other shades.” Porteous, Mitchell & Braun used a full page to announce it would close on Saturday afternoon out of respect. “Though we live in a ‘commercial’ age, admiration and appreciation for deeds brilliantly conceived and carried through, is strongly entrenched in the minds and hearts of the people of Maine,” the store proclaimed. Eastman Bros. & Bancroft, anther department store, announced that it would close early, too, but refrained from lofty rhetoric.

In Boston, Lindbergh and his team took stock of the bad weather. Reports cited dense fog all the way into Maine, but Lindbergh was determined to make the flight on schedule. “It isn’t as bad as it looks,” Keyhoe remembered him saying. “The flying won’t be hard; I’ve seen worse days on the mail. The only trouble will be at Portland, if the airport is covered with fog.” Keyhoe asked Lindbergh not to take any chances. “I’ll be all right,” the young aviator said. “With these instruments I can get through the fog, and if I can’t find Portland Airport I’ll drop in somewhere else.”

Lindbergh climbed into the Spirit of St. Louis’s tiny cockpit and took off into the mist. Love preferred to fly alone in the support plane in such dangerous conditions, so Keyhoe and Sorenson drove. It was a tense and worrying trip. As the two men neared Portland, they noticed a procession of cars and decided to follow them. The cars led them to Love, who had been forced by the fog to land in a field. Love said he had heard the Spirit of St. Louis flying somewhere in the clouds above him.

UNEXPECTED STOP

Portland, it turned out, was completely socked in. After circling fruitlessly around the city for more than two hours, Lindbergh decided a landing was impossible, so he flew toward New Hampshire in the hopes that the weather was better there. He landed in Concord and postponed his Portland appearance for a day.

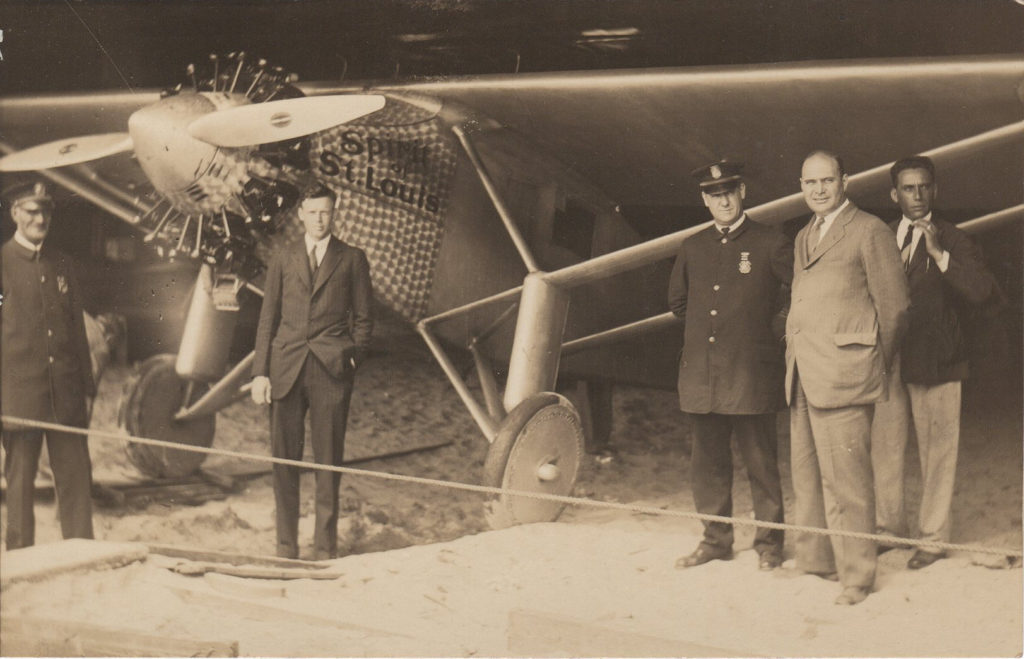

The weather was no better on Sunday when Lindbergh took off from Concord. As he had the day before, he circled around Portland for more than two hours in a search for the fogged-in airport. He finally spied Old Orchard Beach through a break in the clouds and decided to land there. He made a perfect landing and taxied up to a little airfield run by Captain Harry Martin Jones.

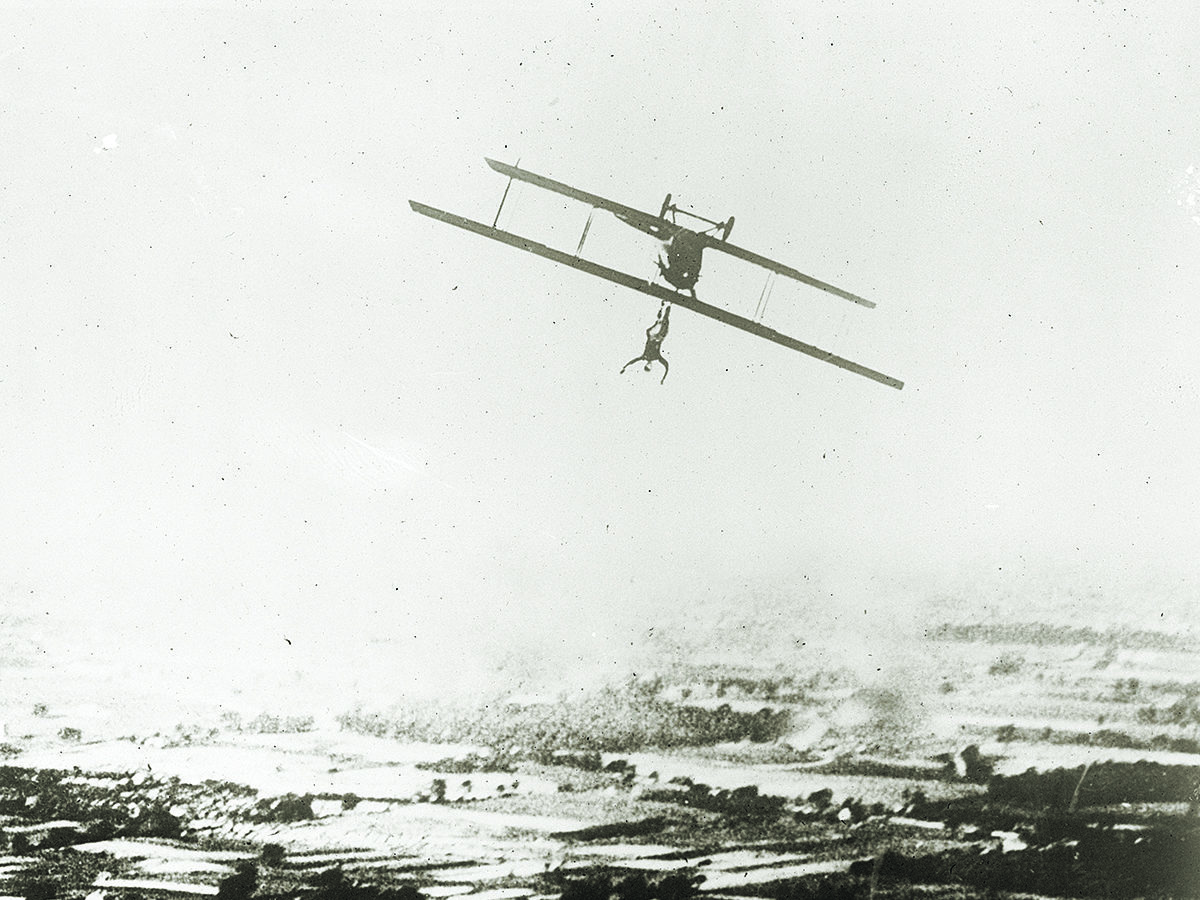

Like Lindbergh, Jones was an aviation pioneer. He had created a sensation in 1912 when he made the first (and last) landing on Boston Common. He flew the mail between Boston and New York for a time before setting up shop on Old Orchard Beach in 1919, offering flying lessons and giving airplane flights to tourists from his beach airstrip. He charged $25 for a round-trip flight from the beach to Portland. Old Orchard Beach even made Jones its first (and last) “aerial policeman,” complete with uniform.

THE MOST FAMOUS MAN IN THE WORLD

The arrival of the most famous man in the world at Jones’s hangar must have come as quite a surprise. Mechanic Austin Thomas was the first man to greet Lindbergh, followed by Roy E. Haines, who was in town overseeing a toy factory he owned. Thomas and Haines helped Lindbergh push his airplane inside Jones’s hangar before the gathering crowd could mob him. Haines offered him a ride to Scarborough but couldn’t get his car to start. A nearby homeowner offered his vehicle and Lindbergh and company set off. Keyhoe and a delegation from the welcoming committee met them on the way.

Other than the tricks played by the weather, Lindbergh’s visit went off almost without a hitch, except when a car backed out of a driveway and hit state policeman Eugene Stevens, part of Lindbergh’s motorcycle escort from the airport. Stevens suffered only some bruising and was gratified to receive a note and a box of candy from Lindbergh as he recuperated at Maine General Hospital.

Thousands of people lined the route into town, despite the threat of rain. “At every corner, crowds had congregated and the whole countryside seemed to have been swept with a wave of madness,” the Press Herald reported. “Men and women screamed out their greetings, and above their voices rose the shriller cries of excited children.” The guest of honor sat in the back seat of the car, bowing to the crowd. At one point people broke through the lines of police and swarmed into the street. After order was restored, Lindbergh finished the parade and was brought to the Eastland Hotel for a short rest before the afternoon’s events. While he was there, the “little blonde” who operated the hotel’s elevator couldn’t resist temptation, and she surprised Lindbergh with a bear hug.

The 25,000 people who crowded into Deering Oaks that afternoon were a little less than the 30,000 predicted. In his talk to the crowd, Lindbergh referred to his issues with the weather but pointed out how technological developments in radio would soon let pilots land in the densest fog. Lester Ayer must have done his job well, for the Press Herald boasted that “Perfect Order Prevails While Amplifiers Enable Every Word To Be Heard.” (The paper also pointed out that, according to police, pickpockets managed to extract $289 from unsuspecting celebrants.)

Lindbergh repeated his belief in aviation’s future that night at the Eastland, touting developments in radio beacons, deicing equipment, and compasses. “In a few more years, planes will be flying in every kind of weather condition and schedule,” he predicted. “Airports must be built, as you have done here in Portland. Build for the present, and plan for the future, too.”

Seven hundred people enjoyed the festivities at the Eastland, while hundreds more waited outside, hoping for a glimpse of the guest of honor. One man who made his way up to the head table was Lindbergh’s great-uncle, John C. Lodge of Detroit. Lodge was spending the summer in Poland Springs, but he traveled the 30 miles to Portland to see his famous nephew. Earlier that day he had tried to visit Lindbergh at the Eastland but Keyhoe, not believing Lodge’s claim of kinship, denied him admittance.

During the dinner, someone opened a door in the back of the room so spectators waiting outside could catch a glimpse of the Lone Eagle. “Fathers and mothers held simpering infants up in their arms, so that some day they can tell their own children they saw Lindbergh,” said the paper. “‘Lindy’ is America’s greatest drawing attraction. Showmen must weep when they hear about his reception.” It was, according to the Press Herald, “Portland’s biggest day in many a year.” It was even bigger for Mary Elizabeth Skerrit, the wife of a Portland policeman. At 5:05 that morning she gave birth to a son. The proud parents named him Charles Lindbergh Skerrit.

CLOSE ENCOUNTER

Lindbergh’s delayed arrival in Portland came as a great disappointment to Elise Fellows White. Something of an aviation fanatic, White was determined to see the Lone Eagle. She managed to reach Portland on Sunday but arrived too late to see Lindbergh at Deering Oaks and policemen stopped her from entering the Eastland Hotel. Once back home she burst into tears.

The next morning, she took a train to Old Orchard Beach, made her way to Jones’s hangar, and spotted the Spirit of St. Louis through its open doors. “I found myself transported from the other place straight to heaven,” White wrote in her diary. She ducked under the rope that Jones had strung up as a barrier and managed to touch one of the plane’s wings.

Lindbergh arrived in a car shortly afterward. “His face was delightfully ordinary, just a clean-cut average western boy’s face,” White wrote. “He might have been working in a hayfield or running a tractor.” The weather had improved and after tinkering with his plane and talking with men in the hangar, Lindbergh emerged and tossed some seaweed into the air to check the wind. Police kept the crowd back as men pushed the Spirit of St. Louis onto the beach. Lindbergh climbed into the cockpit and started the engine. Some volunteers had to push to extricate the wheels from the wet sand, and then Lindbergh started his plane on its takeoff run down the beach. “It moved smoothly over the sand and in no distance at all — hardly more than a hundred yards — it was in the air,” White wrote. “He tipped and banked and turned swooping low over the beach then rose like a silver winged bird against the blue sky.”

GOODBYE, PORTLAND

Lindbergh flew over Portland one more time, giving residents a chance to see his airplane. Then he turned toward Scarborough and finally landed at the new airport. He bid farewell to his reception committee and praised the airfield before taking off for his next official stop in Concord, New Hampshire. Along the way he made a short detour over Poland Springs to provide an aerial greeting to his mother’s aunt, who had not been able to travel with John C. Lodge to Portland. “‘We’ came, ‘we’ saw, ‘we’ conquered,” said the Press Herald, using the personal pronoun Lindbergh used to refer to himself and his airplane, “and both Col. Charles Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis left broken hearts behind him when he left Maine, for his charm and modesty won him followers who will never be able to forget him.”

By the time Lindbergh finished his tour in late October 1927, he had visited all 48 states and stopped in 82 cities. He was late only once — when fog kept him from landing in Portland, Maine.

Adapted from “Maine at 200: An Anecdotal History Celebrating Two Centuries of Statehood” by Tom Huntington. ©2020. Published by Down East Books. Tom Huntington is the editor of Aviation History magazine. For further reading he recommends Donald E. Keyhoe’s “Flying with Lindbergh.”

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.