When Germans, Americans, Italians or Belgians think of World War I aviation, the first names that come to mind are usually their highest-scoring fighter pilots—Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen, Edward Rickenbacker, Francesco Baracca and Willy Coppens. An exception is France, which most reveres its second-ranking ace, Georges Guynemer, among its martyred heroes, while the higher-scoring René Fonck settles for posterity’s grudging respect for his wartime achievements. A less romantic, more practical mind might note that Guynemer literally burned himself out in his single-minded patriotism, making his death, in September 1917, almost inevitable. Fonck, in contrast, flew, fought and lived by a philosophy that dying for one’s country was less desirable than making one’s opponent die for his. Cynical though that outlook seemed at the time, it was arguably more mature and better suited for a fighter pilot’s success—and survival. But perhaps Fonck’s biggest problem compared to Guynemer was that he survived.

Born in Saulcy-le-Meurthe on March 27, 1894, René Paul Fonck grew to be a rather short, unremarkable-looking young man whose own self-serving writings suggest ambitions at least partially driven by an inferiority complex. He claimed that his upbringing in the Alsace-Lorraine region, seized by the Germans after the humiliating Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, had imbued him with a desire for revenge. When World War I broke out, he was mobilized on August 22, 1914, and assigned to the 2nd Groupe d’Aviation at Dijon. He was transferred to an engineer unit a month later, but by then Fonck had made up his mind that the new and rapidly developing airplane was his most promising ticket to glory. On February 15, 1915, he managed to get reassigned to St.-Cyr for flight training.

After earning his pilot’s brevet at Le Crotoy, on June 15 Corporal Fonck was assigned to Escadrille (squadron) C.47 based at Corcieux, not far from his hometown. Fonck considered the unit’s Caudron G.3s “slow and cumbersome,” and after encountering a German plane while returning from reconnaissance over Colmar, he wrote that he “no longer took off without carrying a good carbine.” On July 2, Fonck attacked an enemy plane over Münster, but the German retired none the worse for wear. He had several other inconclusive aerial encounters and survived having his engine disabled by an anti-aircraft shell burst, which compelled him to force-land in Allied lines.

In October C.47 switched from G.3s to twin-engine Caudron G.4s, and Fonck flew 13 long-range recon missions and 24 artillery-spotting flights during the month. Some of the G.4s carried cameras, which as Fonck noted in his autobiography, Mes Combats, “gives a clearer and more exact map, once corrected and adjusted for scale, than the work of the best professional geographer.” He also observed that German anti-aircraft fire was intensifying. During a photoreconnaissance mission in June 1916, a shell tore through Fonck’s right wing, missing his nacelle by less than a yard. “If the projectile had exploded on contact with my wing, my fate would have been sealed,” he wrote. “I am not ashamed of the slight case of shivers that I still experience at this memory.”

In July Fonck mounted a Lewis machine gun to fire forward over his Caudron’s upper wing. During one mission that month, a shell burst disabled one of his engines, but he returned on the remaining motor. Then, while Fonck and his observer were photographing the Roye area on August 6, two Fokker E.III fighters tried to interfere. Fonck aggressively attacked and saw one Fokker dive toward its lines, while the other retired. The Frenchmen resumed their photographic work until Fonck noticed French anti-aircraft fire directed at two Rumpler C.Is over Estrées-Saint-Denis. He dived on them, and when one broke away, Fonck gave chase, matching its turns while its observer fired random shots at him. “For twenty minutes at least, from bank to bank and spiral to spiral,” he wrote, “we descended from an altitude of 4,000 meters until we landed on a grassy field where, their will broken, two Boche officers surrendered—the only prisoners I ever took.” German records noted that 2nd Lt. Hermann von Raumer and Reserve 1st Lt. Adam Brey were taken prisoner that day.

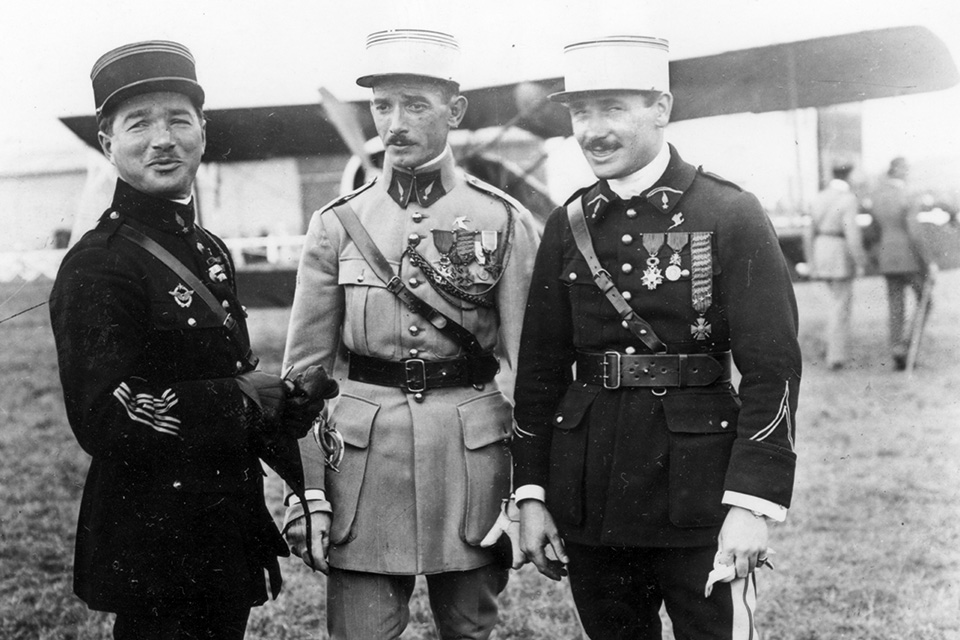

On March 17,1917, Fonck and his observer helped bring down an Albatros north of Cernay-en-Laonnais. Fonck was clearly more fighter than recon pilot material, and on April 25 he was transferred to N.103 of Groupe de Combat 12. Also known as “Les Cigognes” for the stork emblems that graced the sides of its Nieuport 17s and Spad VIIs, GC.12 was the elite group in the French air service, boasting such renowned fighters as Alfred Heurteaux, Albert Deullin, René Dorme and Georges Guynemer. When Fonck arrived, however, N.103, a bomber unit recently turned into a fighter squadron, had yet to boast an ace of its own. Fonck aimed to be the first.

“I had obtained a new plane, naturally; a brand-new Spad with which I promised myself to do a great job,” wrote Fonck. It took him and his mechanics two days to get the aircraft performing to his satisfaction, but his careful preparations paid off on May 5, when he and three comrades encountered five Albatros D.IIIs over Laon. Sergeant Pierre Schmitter’s plane was hit, and Sergeant Claude Haegelen and Lieutenant Pierre Henri Hervet were hard-pressed when Fonck intervened and fired point-blank at a German who suddenly emerged from a cloud in front of him. “His plane immediately nose-dived to a crash at the corner of a wooded area,” Fonck wrote. His victim, Warrant Officer Anton Dierle of Jagdstaffel (fighter squadron, or Jasta) 24, was killed.

In spite of his genuine accomplishments, Fonck’s description of that action—and of numerous others thereafter—reeks of the vanity he often exhibited around fellow pilots. He did not mix well with others, impressing comrades as being either withdrawn, shy or conceited. Either way, he did not endear himself to fellow fliers.

“He is not a truthful man,” said Haegelen, who was nevertheless one of Fonck’s best friends. “He is a tiresome braggart, and even a bore, but in the air, a slashing rapier, a steel blade tempered with unblemished courage and priceless skill….But afterward, he can’t forget how he rescued you, nor let you forget it. He can almost make you wish he hadn’t helped you in the first place.” Swiss volunteer Jacques Roques summed up Fonck by saying, “As a fighter pilot, in one word, the best…but he was not a very sympathetic character.”

In seeming contradiction to his grating personality, Fonck’s lifestyle was arguably among the most sensible for a fighter pilot of his time. While Guynemer flew relentlessly, and third-ranking French ace Charles Nungesser alternated between fighting, womanizing and drinking, getting barely two hours of sleep at night, Fonck rested between missions, drank moderately and spent much of his leisure time practicing his marksmanship.

Fonck downed an Albatros on May 11, and scored his ace-making fifth victory two days later. He added only one more plane to his score over the next two months, but as Fonck described it, it was not without significance:

I was out on patrol very early on the morning of June 12 and discovered two Albatroses which were climbing. Instantly I followed them in their maneuvers and suddenly pounced on them with the sun at my back….I saw them clearly stand out against the sky, which seemed to get lighter at each moment, while they must have had an unclear vision of me in the blinding rays of the sun. I realized immediately that I had to deal with two seasoned veterans, but the first appeared to fly straight in the direction of his lines. The other came around to meet me with determination….In this way, with one behind me and the other in front, they were going to fire at me together at their ease. I had the impression at that moment that my life was hanging on a thread, and to avoid an imminent bullet, I risked an abrupt turn which would bring my adversary into my field of fire. His next attempt was unfortunate and his bank too slow. I was able to empty my band of cartridges into him broadside. His disabled plane rapidly nose-dived—the pilot himself killed by a bullet in the throat. His companion tried to take advantage of the situation in order to escape me, but it was too late. I immediately overtook him and shot him down, too.

Information found on one of my two victims showed that my victory was going to take on the proportions of a catastrophe in Germany. I had brought down Captain Von Baer, the commanding officer of one of their best fighter squadrons. He had twelve victories to his credit and was considered one of the enemy’s most skilled pilots. I was warmly congratulated.

Fonck’s postscript was not entirely correct, although he had in fact killed an enemy of some stature. Reserve Captain Eberhard von Seel had no victories to his credit, but he had taken command of Jasta 17 on May 10—little more than a month before Fonck terminated his career.

In late July, when GC.12 moved to Dunkirk in the Flanders sector, to face some of the best fighter squadrons in the German air service, the aerial action heated up considerably. On August 19, Fonck embarked on a winning streak, downing an enemy plane daily until the 22nd.

Shortly after GC.12’s arrival in their sector, some British pilots arrived to familiarize its personnel with their aircraft. During that visit Corporal Louis Risacher, a Parisian-born flying instructor transferred to N.3 on June 27, recalled an incident that revealed a difference in technique between the renowned Guynemer and the rising star Fonck: “There was a Canadian I remember, one of their aces, I cannot remember his name. He offered to have a mock dogfight with Fonck and Guynemer….Guynemer had the first ‘fight.’ It was decided by Guynemer and the Canadian ace that they would cross in the air and the ‘combat’ would begin at once. Immediately, Guynemer was on his tail and he could not get him off….Guynemer had outmaneuvered a Sopwith Camel in a Spad—absolutely!

“Fonck said, ‘Send me three pilots, and I will attack them. They will never see me.’ Three English pilots started, and were over the field, where we had lost sight of Fonck. Suddenly, there was a Spad flying through the three Englishmen. It was Fonck. That was the difference between the two schools. Fonck was a very good pilot, of course, but he never made a dogfighting maneuver in the air, he always flew flat. Not to be seen by anybody…that was his style.”

On September 11, 1917, Captain Georges Guynemer, victor over 53 German aircraft since 1915, did not return from a patrol. Everyone in GC.12 swore revenge, including Fonck. On September 14, he destroyed a two-seater in flames over Langemarck. “Such was the funeral of Guynemer to me,” he later wrote.

GC.12 left Flanders for Maisonneuve on November 11, and moved to Beauzée-sur-Aire on January 17,1918. By then the group had given up the last of its Nieuports and its squadrons had been redesignated accordingly, including Fonck’s Spa.103. The new year brought new fighters to the group in the form of the Spad XIII, equipped with a 220-hp geared Hispano-Suiza 8B engine and twin machine guns. Ordered into production back in February 1917, the Spad XIII boasted a maximum speed of 124 mph and a climb rate of 13,000 feet in 11 minutes, but problems with the engine’s spur reduction gear had delayed its frontline arrival and would handicap it for months thereafter.

In spite of the Spad XIII’s shortcomings, Fonck found its speed and sturdiness in a dive ideal for his stalking tactics. Adapting to it readily, he downed two opponents on January 19, and by March 17 had raised his score to 30.

On March 21, 1918, the Germans launched the first of several offensives designed to knock France out of the war, and GC.12 was, as usual, in the forefront of the resistance, strafing troops and attacking every enemy plane its pilots encountered. Fonck’s contribution included a victory on March 28, two on the 29th, two more on April 12 and another on the 22nd.

Even during this intense period of fighting, Fonck’s self-absorbed attitude continued to alienate his fellow Storks. Edwin C. Parsons, a former pilot of Escadrille N.124 “Lafayette” who transferred to Spa.3, wrote of how, during one of Fonck’s pompous lectures on air fighting, he and fellow Lafayette Flying Corps volunteer Frank L. Baylies bet a bottle of champagne that they could bring down a German before he could. Fonck accepted, and on May 9, despite hazy conditions, Baylies caught a Halberstadt CL.II between Braches and Gratibus, sending it crashing down in German lines. Back at GC.12’s aerodrome at Hétomesnil, Fonck complained that the bad weather had prevented him from going on patrol and asked that the wager be altered to favor whoever downed the most enemy planes that day. The Americans reluctantly agreed.

Fonck didn’t fly until 3 that afternoon, but an hour later he claimed three two-seaters south of Moreuil that fell within 400 yards of each other in a matter of 45 seconds. Baylies and Parsons set out again at 5:30, but had no further luck. At the same time, Fonck was patrolling with Sub-Lieutenant Léon Thouzelier and Sergeant Jean Brugère, but lost them in some fog. Upon emerging from it, he spotted a German two-seater over Montdidier, which he promptly shot down. Fonck admitted that he was pleased to have lost his wingmen, stating, “I prefer to fly alone in the middle of my adversaries anyway, without having the additional responsibilities of protecting my comrades….I try never to let a comrade down; but above all, I like my freedom of action, for it is indispensable to the success of my undertakings.”

Shortly before 7, Fonck encountered four Fokker D.VIIs with five Albatros D.Vas flying above them. “I hesitated to attack,” he wrote, “but the desire to round out my performance won out over prudence, and I chose the risks of combat.” Diving on the Fokkers, Fonck picked off the trailing plane, shot down the leader eight seconds later and then dived away from the seven remaining fighters. His victims, 2nd Lt. Ernst Schulze and Staff Sgt. Otto Kutter of Jasta 48, were both killed. Curiously, while Parsons stated that Fonck won the champagne, the French ace never mentioned the wager in his memoirs. In any case, Fonck had proved he was more than just an obnoxious windbag, having scored a phenomenal six confirmed victories in one afternoon.

At about that time, two unusual Spads arrived at Spa.103. Designed at Guynemer’s request, the Spad XII used a variation on Hispano-Suiza’s geared engine, the 8Cb, which raised the propeller above the cylinder heads to allow a 37mm Puteaux cannon with a shortened barrel to fire through a hollow propeller shaft. Elegant looking on the outside, the Spad XII was decidedly different inside the cockpit, where the cannon breech protruded between the pilot’s legs, necessitating Deperdussin-type elevator and aileron controls on either side of his seat instead of a central control column. A highly skilled pilot like Guynemer could master such a system, but he was also forced to deal with the heavy recoil of a single-shot weapon that filled the cockpit with smoke upon firing and had to be reloaded by hand. The Spad XII was additionally armed with a synchronized .30 caliber Vickers machine gun that could be used to help sight the cannon on a target or to help the pilot fight his way out of trouble after it had been fired.

Guynemer had scored four victories in the first Spad XII in July and August 1917, and the air service ordered 1,000 cannon Spads. It is doubtful that more than 20 were completed, however, before production problems with the engine and cannon arrangement led to the order being canceled in favor of the simpler Spad XIII.

The few cannon Spads that reached frontline squadrons were usually allocated to pilots of proven ability. These included Spad XIIs S445 and S452, both of which were flown by Fonck—yet his first combat in the fighter was almost his last. On May 19, he attacked five German aircraft from above and sent 20 machine gun bullets into the rearmost plane, which nosed down into a spiraling dive. He also used the machine gun to deal with a second adversary.

“For his part, my buddy Brugère brought down another one,” wrote Fonck in his memoirs, “but Thouzelier, having engine trouble, was at grips with the last two, who furiously tailed him and riddled him with bullets in his descent. Seeing him in such a bad spot, I tried to relieve him by a rapid turn, but as I was flying upside down, my extra cartridges, placed at my side in a case, fell among the controls and one of them got wedged in.

“I felt myself tearing through the air on my back at full speed,” Fonck continued, “and I was afraid at any instant that I would be shot down by the German whom I was about to attack, and who, realizing my critical situation, would follow me firing away with his machine gun. I was carrying a new Spad test gun for the first time, and I also did not know how to maneuver in order to get out of the situation. Believing my situation to be hopeless, I resolved to risk everything. I abandoned the controls and picked up the scattered shells, which I threw over the side one by one. The few seconds this operation took seemed like an eternity to me, but I was finally able to straighten out 1,000 meters below. Never before did I feel death pass by so closely.”

Fonck eventually claimed 11 victories in the Spad XII, of which seven were confirmed. Throughout the summer of 1918, his score rose steadily—often by two or three victories a day. During the last German assault over the Marne River, begun on July 14, he downed two planes on July 16, two more on the 18th and three on the 19th as the French army counterattacked. A two-seater on August 1 was followed on August 14 by three more—within 10 seconds. “They came toward me following each other at 50-meter intervals,” Fonck explained. “Upon crossing them, I cut loose a burst at each one, and each time my bullets hit their target. They fell near the city of Roye and ended up by burning on the ground, separated by less than 100 meters. These were my fifty-eighth, fifty-ninth and sixtieth official Boches.”

On September 26, Fonck took off from La Noblette aerodrome and soon encountered five Fokker D.VIIs. “Without giving them time to work out by signals their plan to attack me,” he wrote, “I dived into their midst at full speed, guns blazing. Letting myself then fly on my wing, I turned over completely in order to rocket up behind one of the planes which already had fired at me. But I also had fired, and two of the German planes crashed to earth in the vicinity of Sommepy. The others, fearing for their safety, had thought it more prudent to take to their heels.”

Regaining altitude, Fonck noticed a Halberstadt two-seater under French antiaircraft fire and attacked it over Perthes-les-Hurlus, killing its observer, Reserve 2nd Lt. Eugen Anderer, with his first shots. “The defenseless pilot became frightened,” Fonck reported, “and his vertical dive was so sudden and steep that his companion, whom I had just sent off to join his ancestors, toppled overboard and almost fell on top of me at the moment of finishing my loop, when I was going to climb in order to attack the two-seater again.” Fonck then sent the plane crashing down minus a wing, killing Staff Sgt. Richard Scholl.

Leading a patrol with three squadron mates that same evening, Fonck encountered eight more Fokkers. “I awaited the attack confidently and would have willingly provoked it when a Spad came in unexpectedly to lend a hand,” he said. “I immediately recognized Captain [Xavier] de Sevin and the ‘Storks’ of the 26th.”

The French attacked, but the Germans gave Fonck one of the toughest fights of his career. Adjutant Brugère downed a Fokker, then was attacked by two others, one of which Fonck shot down in the process of rescuing him. Five Albatros two-seaters entered the melee, and Fonck downed two of them as well. “Two others owed their skins to a jamming of my machine gun,” he stated, “and despite the cold, which perpetually reigns in high altitude, I must confess I felt drenched with perspiration upon returning to the field. But for me, the day had been excellent. I now had sixty-six official victories to my credit.” He had also become the only World War I ace with two six-victory days in his combat log.

Fonck shot down two enemy planes on October 5, followed by three more on the 30th and two on the 31st. His victory over a Halberstadt on November 1 was also the last for GC.12 before the armistice was signed on the 11th, bringing its total to 286 aircraft and five balloons, although if victories prior to the group’s formation are counted, the collective wartime total of its component squadrons came to 411 planes and 11 balloons. The group’s top-scoring squadron had been Spa.3 with 175 victories, but Spa.103 ranked second with a wartime total of 111—73 of which had been scored by one individual: René Fonck.

With 75 confirmed victories—and 52 unconfirmed—Fonck was the undisputed Allied ace of aces, yet he never received the adulation bestowed upon Guynemer and Nungesser. On September 21, 1926, he set out from New York on a nonstop transatlantic flight attempt to Paris, but his overloaded Sikorsky S.35 crashed on takeoff, killing two of its four-man crew. He served as inspector of France’s fighter force prior to 1940. After World War II he was accused of collaborating with the Germans, though he was never brought to trial. While uncounted volumes have been written about Guynemer, the only author who wrote a book devoted to Fonck was Fonck himself. He was 59 when he died in Paris on June 18, 1953, an unrequited seeker of glory whose deeds could easily have spoken for him eloquently enough by themselves—if only he had let them.

Aviation History research director Jon Guttman is the author of several books on World War I aviation, including Groupe de Combat 12, “Les Cigognes.” For further reading, he recommends: The Storks, by Norman Franks and Frank Bailey, and Ace of Aces, by René Fonck.

Originally published in the September 2009 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.