For his third film, acclaimed director Mike Nichols decided to adapt “Catch-22,” Joseph Heller’s pitch-black satire of war, madness, the military and capitalism. The book focuses on American bomber crews at an Italian base during World War II, and Heller based it on his own experiences as a bombardier on North American B-25 Mitchells of the 488th Bombardment Squadron (Medium) in the Mediterranean.

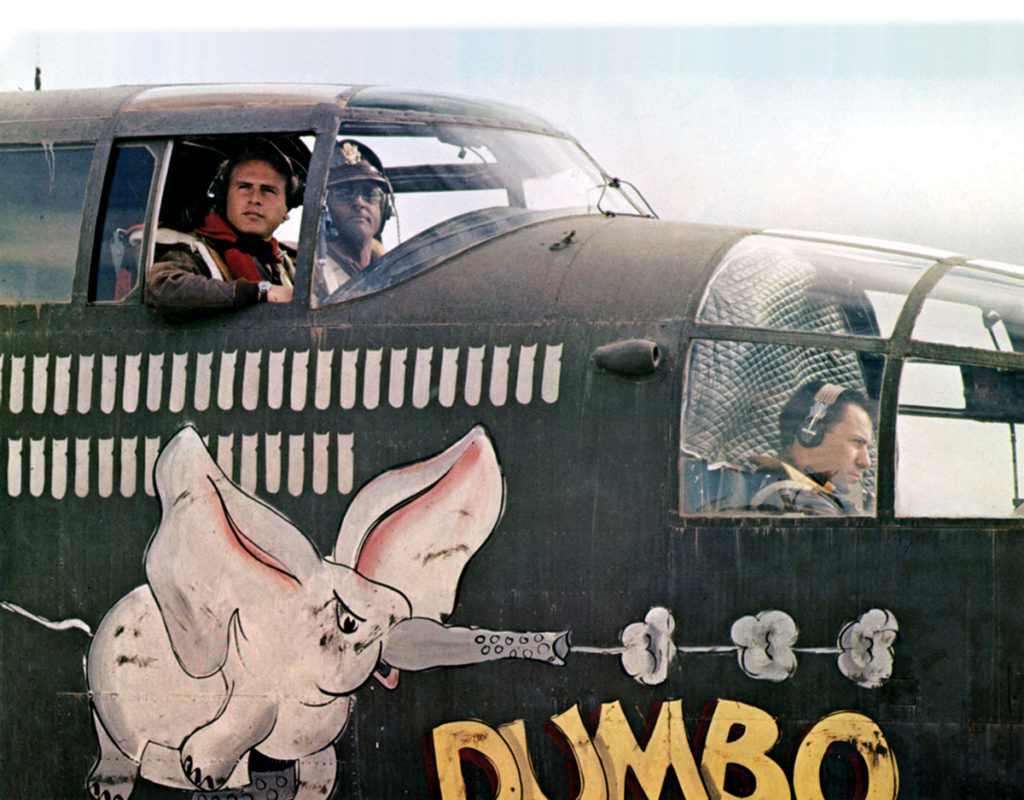

There was a catch, though: To create a realistic foundation for the dark comedy, Nichols needed to assemble a squadron of B-25s. This was in 1969, long before filmmakers could rely on computer-generated imagery to create fleets of bombers with software. Instead, Nichols had to enlist his own air force. He ended up with 18 B-25s, the largest group of Mitchells flown since the war ended.

Recommended for you

A Different Kind of War Movie

Nichols did not set out to make a flag-waving film like the war movies produced during World War II or its immediate aftermath, when Americans felt unalloyed pride in the country and the war effort. That attitude began to shift during the turbulent 1960s as the Vietnam War led to a growing distrust of government. Pride in the American armed forces reached a low ebb at the time, an attitude reflected in films produced between 1965 and 1979. One example is Robert Altman’s “M*A*S*H” (1970), a film set during the Korean War that was clearly commenting on the American experience in Vietnam. “Catch-22” would be another film that looked at war and warmakers with a jaundiced eye.

Both the film and the book tell the story of Capt. John Yossarian (played by Alan Arkin), a B-25 bombardier flying out of a small Italian island in the Mediterranean. Yossarian is desperate to get out of the war and the only way to accomplish that is to convince his commander he is insane. And there lies Heller’s famous catch.

“In order to be grounded, I have to be crazy,” the film’s Yossarian says in a conversation with the base’s doctor (Jack Gilford). “And I must be crazy to keep flying. But if I ask to be grounded, that means I’m not crazy anymore, and I have to keep flying.”

“You got it,” replies “Doc” Daneeka. “That’s Catch-22.”

Planning the Shoot

After its publication in 1961, Heller’s novel became a bestseller and its title entered the cultural lexicon, yet the book’s episodic nature made it appear inherently unfilmable. Heller tried and failed to turn his work into a screenplay. Nonetheless, Paramount Pictures approved the project, with Nichols directing and Buck Henry assigned to turn the sprawling novel into a script. “Catch-22” would be Nichols’ third film, following “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” (1966) and “The Graduate” (1967).

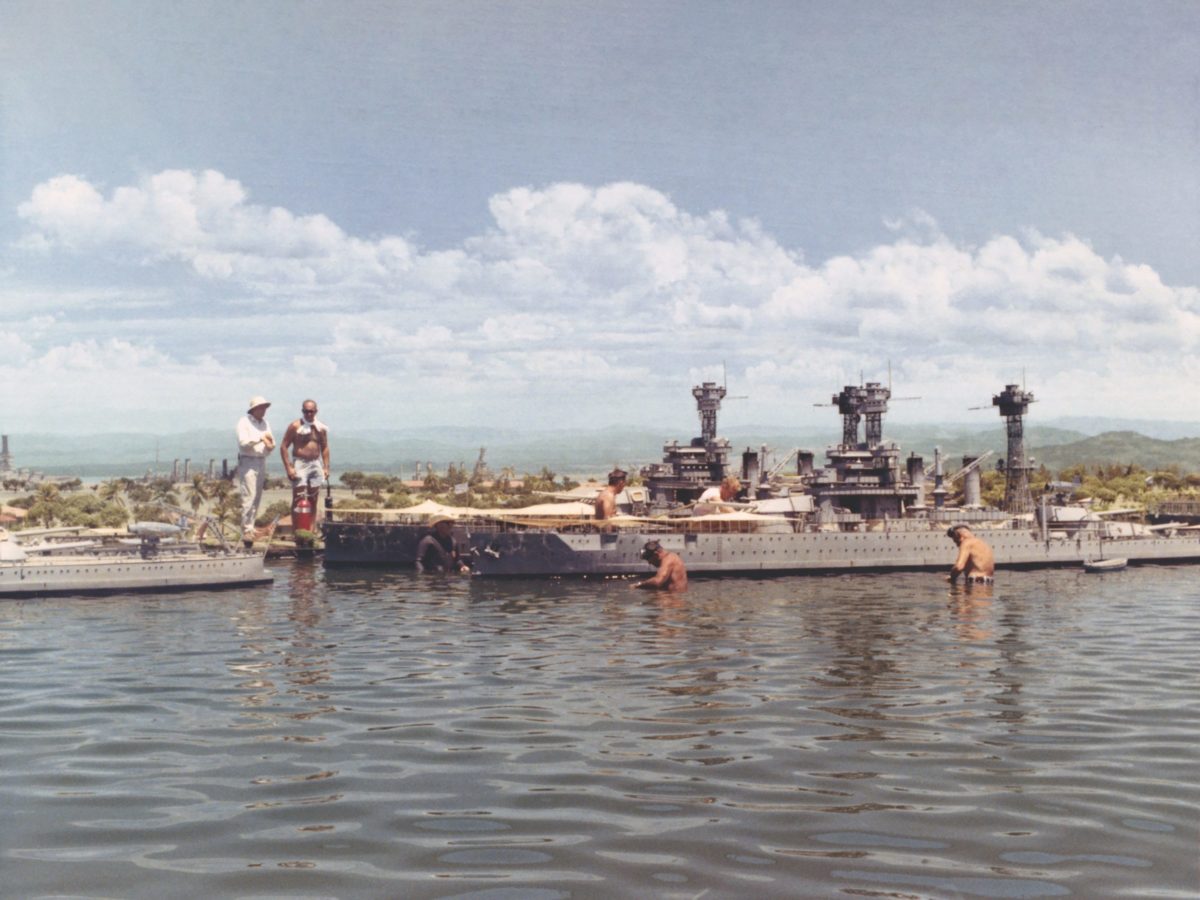

After putting together a workable screenplay, the next hurdle was finding a filming location. Nichols traveled to Tunisia and Italy, seeking suitable stand-ins for the novel’s island of Pianosa. But the landscape had changed too much in the quarter-century since the war ended. Instead, Nichols found what he needed much closer to home — near the small village of Guaymas in Mexico on the Gulf of California. There the production company spent $1 million to build a World War II airbase, complete with control tower, ready rooms, barracks and a 6,000-foot runway. The entire production was budgeted at $17 million, some of which went to gathering and outfitting the B-25s.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Named after airpower advocate Brig. Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell, the North American B-25 was a twin-engine medium bomber that performed sterling service in every theater in which it served, even flying off the aircraft carrier USS Hornet to bomb Tokyo on the raid led by Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle in April 1942. Mitchells were the scourge of German forces in Tunisia, Crete, Yugoslavia, Sicily, Italy and southern France, and they provided valuable service in the Pacific, China and the Russian front. By the end of the war, American factories had turned out nearly 10,000 B-25s.

The number of surviving B-25s had dwindled by the end of the 1960s, so assembling 18 flyable Mitchells was no mean feat for Tallmantz Aviation, the company charged with creating and operating Nichols’ air force. The company, based in Santa Ana, California, had been founded in 1961 by stunt pilots Paul Mantz and Frank Tallman. Mantz was killed in 1965 in a crash while filming “The Flight of the Phoenix“. (Tallman would have flown the stunt, but he had broken his leg in a non-aviation accident and would have the limb amputated). Tallman and Tallmantz Aviation carried on without Mantz.

Building the Fleet

Tallmantz had a head start finding the bombers, since it already owned four. To draft the other 14, Tallman and others scoured collections in half a dozen states and found suitable B-25H and J models that they could use. Tallman sought airplanes that he could buy cheaply, but he insisted on craft that still had good wiring and hydraulics, even if they lacked engines. Engines he could replace easily.

“There’s too much money involved rewiring airplanes with the complexities of this type,” he told an interviewer. He also made a point to climb up on top of an airplane to check for corrosion in the wing roots. “If you find any corrosion up there, forget it,” he said.

Only one of the B-25s he found had served in combat overseas. That exception was the B-25J with tail number 44-28925, which rolled out of the North American plant in Kansas City in September 1944 and flew in Italy with the 310th Bombardment Group of the Twelfth Air Force. After returning to the United States following the war, the veteran aircraft served in various roles, including as an air tanker. When Tallmantz purchased it for $1,500, the engines had been removed. Returned to flying status, it received the name “Tokyo Express” for the film.

The Mitchell with tail number 44-29366 was more typical of the airplanes Tallmantz found. It rolled off the assembly line around September 1944 and was assigned to the Army Air Forces Training Command in Georgia and Texas and was based at Barksdale Air Base in Louisiana at the end of the war. There it spent the next several years in pilot, navigator and bombardier training before ending up in the boneyard at Arizona’s Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in 1958. That’s where Sonora Flying Service in California found the airplane and purchased it for $2,000. It had been converted into a fire bomber before Tallmantz bought it.

The other Mitchells had similar backgrounds, flying domestically as trainers for the Army before being converted into cropdusters, air tankers or other uses or sent to the boneyard. It’s safe to assume that many of these airplanes would not have survived much longer had it not been for “Catch-22.”

Tallman’s Camera Plane

Tallman was already using B-25 43-4643 as a camera plane. After being completed at the North American plant in Inglewood, California, the airplane was assigned to the USAAF Domestic Unit in March 1944 as a TB-25H trainer. Declared surplus in October 1945, it was sent to Stillwater, Oklahoma, for disposal. Mantz had discovered the airplane there and converted it into a specialized camera plane that he used to shoot footage for “The Best Years of Our Lives” (1946), the Academy Award-winning film about war veterans starring Fredric March.

By 1952, Mantz had fitted the B-25, now bearing its civil registration of N1203, with a large glass nose to accommodate the bulky three-lens camera for the new widescreen Cinerama process. He used the Mitchell to shoot nearly all the aerial footage for the ground-breaking 1952 film “This is Cinerama,” including a dangerous flight through a volcano’s smoking crater. Fitted with additional cameras in the waist, tail, top and belly, the plane also shot footage for “Around the World in Eighty Days” (1956), “The Wings of Eagles” (1957) and “Fate Is the Hunter” (1964). It also saw service for “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” (1963), “Von Ryan’s Express” (1965), “The Thousand Plane Raid” (1969) and 1965’s “Flight of the Phoenix,” the production in which Mantz was killed.

War Paint

Once he had assembled his fleet, Tallman needed to convert the old bombers to wartime configurations. That meant adding working bomb bay doors, machine guns and turrets. He found a company selling surplus ordnance in New York where he could get “turrets, guns, bomb racks, shackles, all kinds of stuff,” and he tracked down as many spare parts as possible. Initially the filmmakers installed cameras in turrets behind the wings of several Mitchells so they would represent early war models, but problems with buffeting required their removal.

The production needed experienced crews to man the vintage aircraft it had found, so Tallmantz’s director of operations, Frank Pine, and its chief pilot, Jim Appleby, set out to recruit pilots. One qualification: military flying experience. Appleby, who died in September 2010 after working on such films as “The Great Waldo Pepper” (1975) and “The Stunt Man” (1980), was a stickler for safety and never permitted any pilot to divert from his iron-clad rules.

“We knew it was going to be a military type operation with a lot of tight, possibly dangerous formation flying, so we wanted people who knew all the signals, that we could rely on in a pinch, and who we didn’t have to train from the ground up,” he said. “Quite a few of the guys had flown B-25s either during World War Two or Korea.”

In the end, Tallmantz recruited an additional 32 pilots. “We turned out a damned fine grade of pilot,” said Tallman, who credited Appleby with “setting up a real Air Force training program” that included checkouts, emergency procedures and handbooks on the B-25.

Zona Appleby recalled the training her late husband gave his pilots: “Jim spent a week training the pilots in formation flying and takeoff, air-to-air filming and other skills needed to make the combat sequences authentic,” she said. “Jim insisted on safety above all.”

By the time filming started on Jan. 11, 1969, all the pilots had received their ratings for the twin-engine Mitchells. In small groups they flew to the recently constructed air base, where each bomber was repainted with Twelfth Tactical Air Force and fictional bomb squadron insignia, right down to risqué nose art. The squadron’s patch of a nude woman riding a bomb was taken from the patch of Joseph Heller’s own 488th Bomb Squadron.

The Cameras Roll

The first scene filmed with the B-25s proved to be a hair-raising test for the pilots. The sequence had all the available bombers take off in formation as the cameras rolled. And rolled again (Tallman recollected that it took 13 different takes to get all the necessary footage).

“That was kind of dangerous,” Zona said. “They just took off one after another and had to get into the air. Jim was somewhere in the middle of the pack. Each plane had to get off the ground or crash in the bay lest the following B-25 crash into it from behind. It was that close.”

Tallman said it was “one of the most dangerous stunts I’ve even been asked to do.”

Jim Appleby recalled that he told his pilots that they had to either take off or get out of the way quickly: “I was positioned about halfway with Frank Pine behind me, with cameras rolling. We all went to maximum continuous takeoff power and started rolling down the runway at two second intervals. It took every bit of strength of both pilots to keep the airplane under control and get it in the air, but we all managed to get through it and live to tell about it.”

The powerful blast from the Curtiss-Wright R-2600 Twin Cyclone 14-cylinder radial engines blasted dust and gravel for hundreds of yards.

“They told us later that the prop wash was so strong that it blew a military weapons carrier with an 800 mm lens mounted on it end over end, destroying both the vehicle and the camera,” Appleby recalled.

There were other risky maneuvers for the pilots to perform for Nichols’ cameras, including a scene with a B-25 bombing its own airfield at night as Yossarian runs along the runway and explosions light up the darkness.

“It was a fantastic shot and Alan Arkin is loaded with guts,” Tallman said. “I could see his face as I flashed by at night.”

Crash Scene and Tragedy

One of the Mitchells, originally assigned tail number 45-8843, was intended only for a crash scene. Found in Mexico and repaired to just-flyable status, it was flown to the Guaymas location with its landing gear down for safety reasons. There it was used for a scene in which Lt. Milo Minderbinder (Jon Voight) and base commander Col. Cathcart (Martin Balsam) are blithely conversing about eggs when the B-25 comes into the frame from the right, skidding and screeching across the shot. Minderbinder and Cathcart take no notice as the sound of a crash erupts offscreen. As they get into a jeep and drive away, the bomber’s burning wreckage appears behind them and an ambulance comes screaming down the runway. After the shoot, a bulldozer pushed the charred remains of the airplane into a large pit, where they remain to this day.

Aerial and ground filming lasted until April. Despite 1,500 hours of flight time accrued by the Mitchells, they appear on film for little more than 10 minutes. Tallman later lamented that nearly 15 hours “of the most beautiful aerial footage ever taken of the B-25” just ended up in storage in Paramount’s film library.

There was one airplane-related tragedy during the shoot, but it didn’t involve the aircrew. Second unit director John Jordan — who had lost a leg to a helicopter rotor while working on the James Bond film “You Only Live Twice” (1967) — was filming from the tail-gunner position of Tallman’s camera airplane when he leaned out to take some still photos. He was not wearing a safety harness, and he slipped and fell to his death.

Mixed Release

Twelve weeks of process and studio filming wrapped in August. Despite the superb work of Tallman, Appleby and Pine with the B-25s, the film proved to be a financial disappointment and left audiences indifferent to its sometimes surrealistic and bleak humor. (The New York Times’ Vincent Canby, however, called it “the best American film I’ve seen this year” and Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it “an admirable piece of filmmaking.”)

Catch-22 was released the same year as “M*A*S*H” but did not experience the same success. “M*A*S*H” spawned a long-running television series, while an attempt at a “Catch-22” series, starring Richard Dreyfuss as Yossarian, never made it past the pilot stage in 1973. However, a new adaptation of “Catch-22” appeared in 2019 as a six-part miniseries. It used two actual B-25s — No. 44-30423 from the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino, California, and 45-8898 from the Tri-State Warbird Museum in Batavia, Ohio — but it could also put more bombers on screen with the CGI imagery that Nichols lacked.

Despite the initial reaction, Nichols’ film has gained in stature over the years. And the silver lining for warbird aficionados is that “Catch-22” saved many B-25 Mitchells from the scrapyard or decay. After filming, the Mitchells returned to the Tallmantz facility in Orange County while Paramount considered further options for their use. None came to fruition and the fleet was sold off between 1971 and 1975. Many of the Mitchells are now in museums.

The Nichols film offers a rare glimpse at what B-25 operations looked and sounded like in World War II, something CGI can’t really capture. Maj. Truman Coble, who flew more than 50 missions against Italian and German targets with the 310th Bomb Group out of Corsica, was one veteran who enjoyed the realism of the airplane sequences.

“They did a good job of showing how miserable and hot it was there,” he said. “I got nostalgic seeing those Mitchells flying.”

Frequent contributor Mark Carlson wrote “Flying on Film: A Century of Aviation in the Movies, 1912-2012” and “The Marines’ Lost Squadron: The Odyssey of VMF-422.” Further reading: “Mike Nichols: A Life,” by Mark Harris, and “When Hollywood Ruled the Skies,” by Bruce Orriss.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.