We all know Hollywood flew Zeros—albeit doctored T-6s—in Tora! Tora! Tora!, a Lockheed Electra in the recent Amelia and B-17s in Memphis Belle, but what about the more obscure machines used over the years in films that weren’t necessarily “airplane movies”? There are many, for filmmakers have long relied on aircraft to generate excitement, particularly before the car chase was invented. Remember the Stearman cropduster in North by Northwest? The Curtiss biplanes swarming around King Kong on the Empire State building? The thoroughly bad model of a malformed Lockheed twin shown at the end of Casablanca?

Here’s a small sample of films that used largely forgotten aircraft before computer-generated imagery became commonplace. Today an armada of MiG-35s is only a keyboard away, and programmers can get the “Spruce Goose” out of ground effect and on its way to Hawaii infinitely more easily than eight R-4360 Wasp Majors ever could. But not long ago, casting a plain old war-weary B-25 in a movie required airworthy iron, lots of 115-octane fuel and a film pilot with big brass balls.

The Last Flight of Noah’s Ark

When Elliott Gould starred in this 1980 film, there were enough B-29s still around that Disney Studios used up five just to tell the silly story of an itinerant freight pilot who gets lost and crash-lands off a Pacific island with a cargo of animals. (Novelist Ernest K. Gann wrote the plot, believe it or not.) One B-29 actually flew—Fertile Myrtle, which in fact was a Navy P2B-1S long-range-search version of the Superfortress—and another was cut up to create the raft that took Gould and his menagerie back to civilization. The others played casual roles as crashed B-29s. The cockpit and forward fuselage of a sadly dismembered Fertile Myrtle are today in the International Sport Aviation Museum, in Lakeland, Fla.

Murphy’s War

Frank Tallman flew a Grumman J2F-6 amphibian for this Peter O’Toole tale of a merchant seaman who, after his ship is sunk by a U-boat, finds the Duck that had been aboard the freighter, teaches himself to fly it and sets off in search of the sub. This required Tallman to do lots of spectacular cascades-of-whitewater taxiing, porpoising takeoffs, cross-controlled near crashes and the inevitable bongo-bounce water landing. Throw in a couple of loops and a roll (O’Toole’s character apparently learned quickly) and the movie becomes a remarkable ode to a classic waterbird. O’Toole, famous for doing many of his own stunts, claims to have “flown” the Duck for the film, though the truth is that he taxied it a lot.

Forever Young

Mel Gibson plays a B-25 test pilot who in 1939 is cryogenically frozen and brought back to life 50 years later to be reunited with his true love. As part of the goofy plot, he and a 10-year-old boy steal a restored B-25 warbird from an airshow. Gibson is aging by the minute as a consequence of his freeze-dried dirt nap, and ultimately the kid has to take the controls to land the Mitchell on a tiny grass field—not a strip but an actual pasture—near the Point Arenas lighthouse at Mendocino, Calif. The landing looks spectacular, but more awesome is the fact that film pilot Steve Hinton actually had to do it for the camera, on slippery grass ending at a sheer cliff over the ocean.

Hot Shots!

The U.S. Navy wanted nothing to do with this high-times spoof of Top Gun, so while the Department of Defense was willing to lend Tom Cruise an F-14 and the carrier Enterprise, Charlie Sheen had to make do with a flattop, “USS Esses,” that was actually a simple wooden deck cantilevered out over the Pacific near L.A., with little gull-gray British Folland Gnats serving as beefy Tomcat stand-ins. (The USN wouldn’t even allow its name to be used, which is why the Gnats bear the fuselage legend THE NAVY.) Yes, the Gnats look like the pull-toys their name suggests, but don’t be fooled: The Indian air force used Gnats in the air war against Pakistan, in the 1960s and again in the early ’70s, and they gave a good account of themselves against Pakistan’s Canadair F-86 Sabres.

Flying Tigers

This was John Wayne’s first-ever war flick, released in 1942, and even though it’s an “airplane movie,” we’re including it here not for the inevitable shark-mouth P-40s (which were actually auto-engined replicas that were only capable of taxiing) but because the little-known 1933 Capelis XC-12 plays a bit part. An ugly Electra-size twin with an odd, bestrutted biplane tail, it was promoted by a California Greek restaurateur, Socrates Capelis, and funded by the owners, it is said, of every Greek diner in L.A. It flew only a few times and then ended up as a Hollywood prop, appearing in 13 movies between 1939 and 1957. The real Capelis was scrapped in 1943, but the scale model that was its long-time stand-in for flying scenes lived on, heaven knows why.

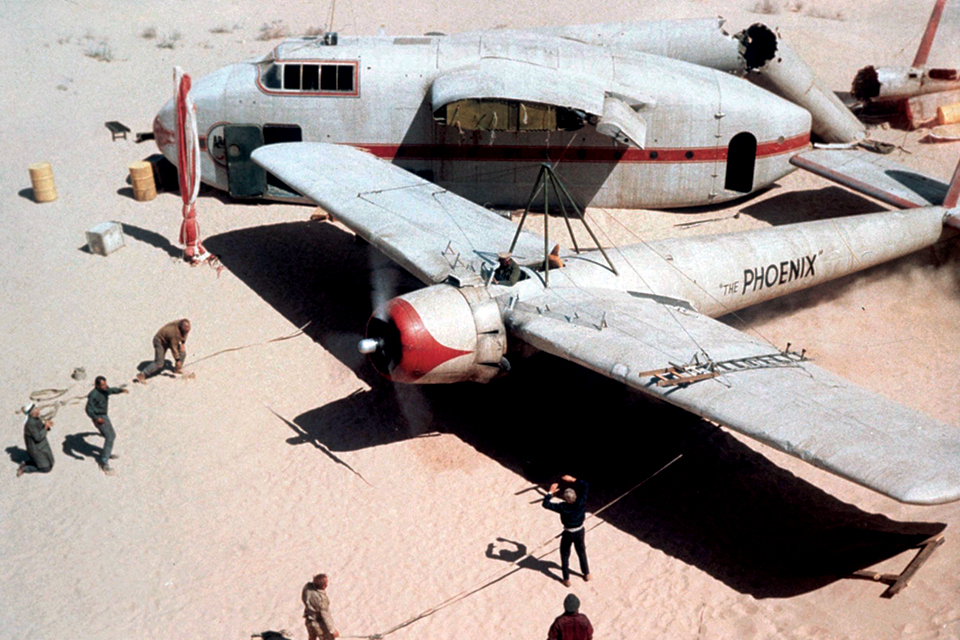

The Flight of the Phoenix

The original 1965 version of this film (badly remade in 2004) is an effective drama of multicultural problem-solving among a diverse group that ranges from a phlegmatic American pilot to the humorless German engineer, stiff-upper-lip Brit officer and a variety of other cliché characters. Paul Mantz died while flying the airplane supposedly cobbled together from parts of the crashed Fairchild C-82A Packet—actually a T-6 Texan engine plus wings from a Twin Beech and a wooden fuselage and empennage. Since the Phoenix was unable to take off from sand, Mantz needed to make a touch-and-go on the desert, and the “go” would be filmed as a takeoff. (The airplane had semi-hidden wheels for runway use.) On his second try, he hit too hard, the fuselage broke and the Phoenix crashed heavily onto its back. With the Phoenix gone, the flying scenes at the end of the film were shot with a modified North American O-47.

Air America

Some call this 1990 epic a comedic adventure; others say it libels the CIA’s resourceful Southeast Asia air wing, since the film recast Air America as a clownish, dope-smuggling outfit crewed by madmen. Sharing a lead role with Mel Gibson and Robert Downey Jr. is a Fairchild C-123K Provider flown for the film by, among others, ex-RAF fighter pilot Mark Hanna, son of Ray Hanna, the first leader of the Red Arrows (the RAF’s Thunderbirds). A C-123K was also signed up to be the flying paddy wagon for the 1997 Nicholas Cage film Con Air, ending up crash-landing on the Las Vegas strip and taking out half a dozen famous casinos. Film mavens point out that the casinos were demolished in improper order, geographically, and that one isn’t even on The Strip, but never mind. Sadly, that Provider crashed for real in Alaska in August 2010, killing its crew of three.

Always

Firebombers occasionally appear on the nightly news when they’re wetting down movie star houses in Malibu, but here’s an entire 1989 Steven Spielberg epic featuring Richard Dreyfus, John Goodman, Holly Hunter and a roaring bunch of radial-engine slurry bombers, with some of the finest Consolidated PBY and Douglas B-26 Invader footage ever filmed. Some consider the opening sequence, an extreme-telephoto shot of a Catalina parting the hair of two fishermen on a previously quiet lake, the best film opening ever. The plot involves angels and ghosts and is too wonderfully complex to summarize, but the spectacular flying was done by warbird specialist Steve Hinton and the late Dennis Lynch, who owned the two B-26s used.

6 Days 7 Nights

Though movie pilot heavyweight Corky Fornof (who flew the Bede BD-5J minijet through a hangar in Octopussy) took the left seat for the hard stuff, star Harrison Ford did some of his own flying for this 1998 romantic comedy about an alcoholic de Havilland Beaver pilot and a strung-out women’s magazine editor, Anne Heche, who crash-land on a remote Pacific island and overcome their initial loathing to fall for each other. The film company’s insurers at first nixed the idea of a flying Ford, since the actor only had 300 hours, but Fornof checked Harrison out in the Beaver, liked what he saw and signed him off. Ford liked the classic bush plane so much he bought a Beaver and still flies it as part of his fleet of seven aircraft. It’s an ex-military DHC-2 fully restored by de Havilland Canada specialists Kenmore Air, and is much prettier than the three flyable and four wrecked Beavers used for the film.

Blue Thunder

This 1983 Roy Scheider explosives extravaganza is the best helicopter film ever made, and it left helicops all over the country lusting for their own Blue Thunders as they cranked up their little Hughes 500s for another day of traffic patrol. Blue Thunder was an Aerospatiale SA-341G Gazelle kitted out with an Apache-style cockpit canopy, a 4,000-round-a-minute chain gun under the nose, stub wings and every electronic surveillance tool known to man at the time, and some that weren’t. Hollywood helo king Jim Gavin and his hugely experienced team of pilots did the often-perilous urban flying between L.A. skyscrapers and under bridges, and aerobat Art Scholl flew one of the camera ships—three years before he was killed in a Pitts while filming for Top Gun. Costar/villain Malcolm McDowell was deathly afraid of flying and would actually be sick between takes.

Tomorrow Never Dies

The Czech-built Aero Vodochody L-39 Albatros was the go-to jet warbird of the mid-1990s—simple, easy to fly, relatively cheap and widely available from corruptible ex–air base commanders throughout the former Soviet Union—so it’s no surprise that several starred in this 1997 James Bond film. The ski-jump takeoff sequence of Pierce Brosnan’s L-39 at the beginning of the film was shot at the 1,100-foot-long, high-altitude Pyrenees airstrip at Peyresourde, France, typically used by STOL planes and microlights. Enough different airplanes and helicopters were used in the film that the crew featured 10 pilots, including Mark Hanna, and a dozen other aerial-sequences personnel. Best shot, literally? Bond toggling the eject-my-backseater switch as he flies under a pursuing L-39, making a human missile of the bad guy sitting behind him.

Miami Vice

Before buzzing off to the junkyard of failed bizplane projects, the push-pull composite Adam A500, derived from a Burt Rutan concept, had its moment in the Florida (and Dominican Republic) sun in this sleek 2006 film that was directed by Michael Mann, who also helmed the influential 1980s TV series. Crockett and Tubbs used the A500 as a cocaine-hauler, which A500 developer Rick Adam thought entirely appropriate—“the ideal aircraft for Miami Vice,” he blithely said before his company went bankrupt. Though Crockett (Colin Farrell) gets command of the film’s Ferrari F430, Tubbs (Jamie Foxx) left-seats the Adam as well as a Lear 60, also seen in the film, as are a Piaggio P.180, a Beech King Air 300 and an Aerospatiale AS360 helicopter.

This feature appeared in the May 2012 issue of Aviation History.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.