In the predawn darkness one day in October 1871 war whoops startled the inhabitants of a Yavapai village atop a plateau known as Iron Peak near Four Peaks in central Arizona Territory.

With the Yavapai warriors away from camp, the Pimas attacked the group of mostly women and children, killing 30 Yavapais. They spared some 16 to 18 children, including a 5-year-old boy named Wassaja and his two sisters. Taken into captivity, the siblings were soon separated.

A week later three Pimas took Wassaja south to the town of Adamsville, intent on selling him. Neapolitan photographer and adventurer Carlo Gentile was in town that day. Filled with compassion at the sight of the terrified, dirt-encrusted boy, Gentile handed the Pimas 30 silver dollars. With a nod, they handed over their captive. The providential encounter forever altered the direction of young Wassaja’s life.

New Clothes and New Name

The next day Gentile took Wassaja into town for a bath, a haircut and new clothes. On November 17 his Catholic Italian rescuer had the boy christened with the name Carlos Montezuma — Carlos after Gentile’s first name, capped with the Spanish “s,” and Montezuma after the nearby ancient ruins known as Montezuma Castle.

At month’s end Gentile resumed his photographic expedition, heading north to the Grand Canyon with his gear and Carlos in tow. In the spring of 1872 the pair crisscrossed the rugged Southwest by wagon, and later that year Gentile and the boy journeyed to Chicago. There they joined writer Ned Buntline, sometime scouts “Buffalo Bill” Cody and “Texas Jack” Omohundro, and Italian dancer Giuseppina Morlachi.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Buntline hired Gentile to produce cartes de visites of his stars and cast 6-year-old Carlos in the role of Azteka, the young Apache captive in his touring production The Scouts of the Prairie. A skit in which he chased an apparently drunken Buntline with bow and arrow played to great laughs. The boy’s acting career lasted but a few months.

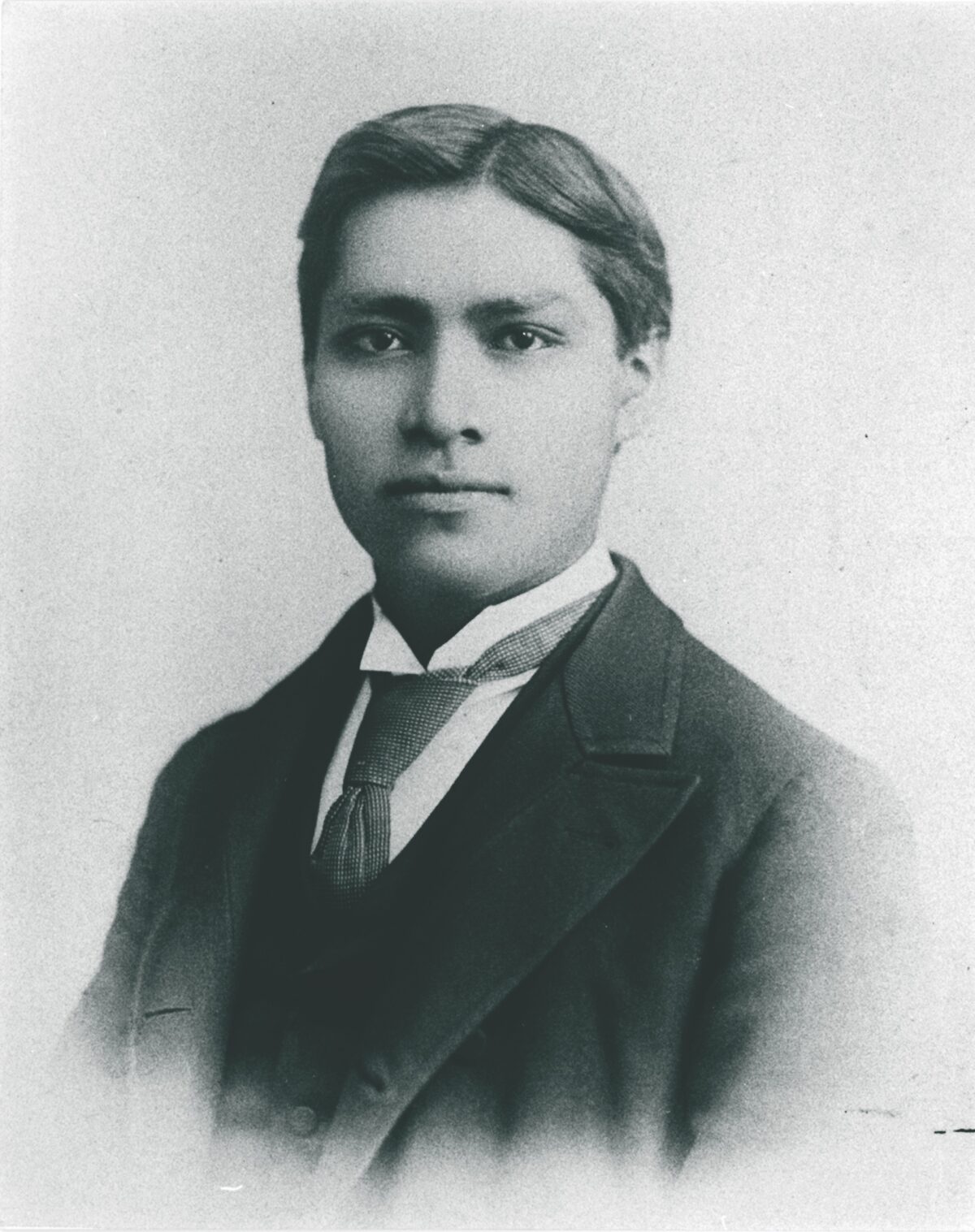

While Gentile plied his trade, Carlos knuckled down to his schoolwork. He proved an exceptional student. In 1880, at only 14, he enrolled at the University of Illinois. After earning a bachelor of science degree, Montezuma enrolled in the Chicago Medical College.

A Doctor at 23

In 1889, having worked his way through school, he both earned his doctorate and obtained a license to practice medicine—quite a feat for any 23-year-old, let alone a onetime captive American Indian boy.

That same year he began serving as clerk and physician of the Indian school at Fort Stevenson, Dakota Territory. In the summer of 1890, after a nasty personal fallout with school superintendent George E. Gerowe, Montezuma transferred to the Western Shoshone Indian Agency in northeast Nevada.

There he tended a mixed population of 550 Shoshones and Paiutes. Conditions were abysmal, and his pleas for funds and supplies fell on deaf ears. Fed up, in January 1893 he transferred to the Colville Indian Reservation in northeast Washington. But conditions there were no better. Montezuma’s pugnacious manner, fiery rhetoric and desire to see the reservation system abolished would keep him at continual odds with the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Determined to give it one more try, in July 1893 he transferred to the Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pa., which lacked a physician. As an advocate for Indian assimilation into white society, Montezuma had found the ideal environment.

Rising Interest in Advocacy

Serving under school founder and superintendent Richard Henry Pratt, his longtime correspondent and mentor, the young doctor remained at Carlisle until December 1895, then returned to Chicago to open a private practice that spanned the next three decades. There his interest spread to American Indian advocacy.

On the morning of April 7, 1904, a train wreck killed three Sioux Indians from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and injured 17 others. Montezuma tended the wounded and followed their progress.

Deeming unfair a proposed settlement between the Pine Ridge agent and the Chicago & North Western Railway, he took up the cause of the injured Sioux. The company had offered a total of $16,900 in compensation, while Montezuma and a committee of fellow Chicagoans suggested $39,700. A court ignored the plea and approved the original settlement.

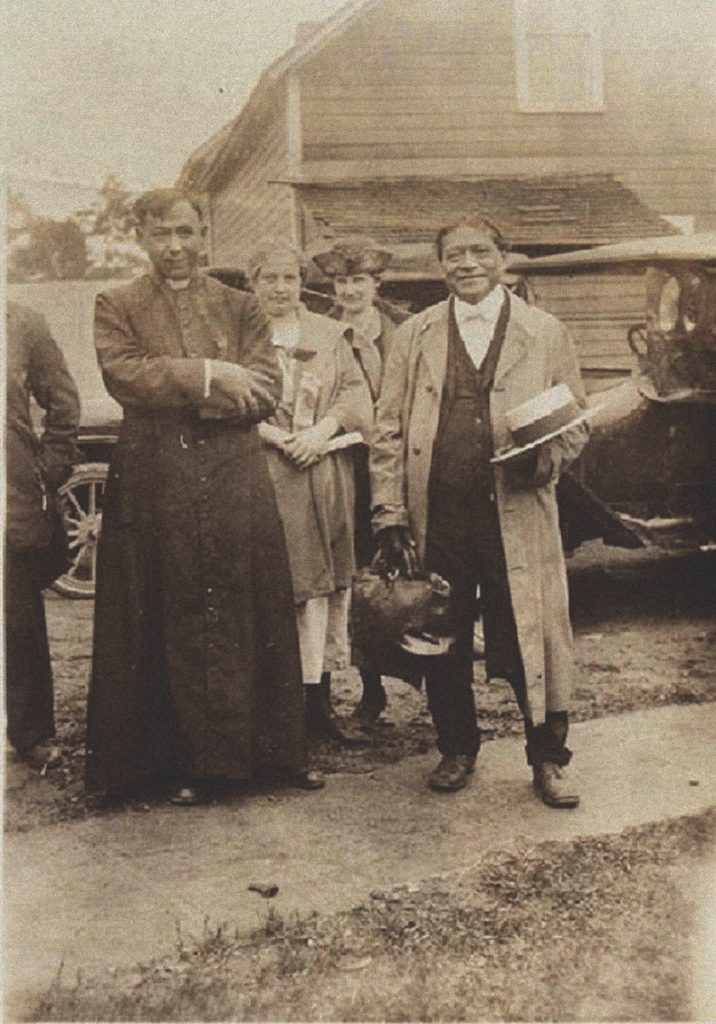

Montezuma had better results when in 1910 he joined an ongoing fray over the land and water rights of his people, the Fort McDowell Yavapais. In a dogged effort that occupied the rest of his lifetime, Montezuma helped the Yavapais retain their lands.

‘Let My People Go’

His advocacy efforts gained Montezuma national prominence. His speech “Let My People Go” was read in Congress in 1916 and appeared in the Congressional Record. That spring he began to promote his views in the self-published newsletter Wassaja: Freedom’s Signal for the Indian, which ran until November 1922.

The choice of his own Indian name for the title was apropos, as it means beckoning or signaling. His primary goal remained abolishment of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, but with America’s entry into World War I Wassaja railed against the injustice of drafting Indians without first granting them citizenship.

Montezuma believed if Indians were to assimilate successfully into white society, they must cast off all vestiges of American Indian culture. Yet in later life he petitioned to enroll as a member of the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation. He lost that battle for a number of reasons.

Labeled a Troublemaker

For one, he’d been labeled a troublemaker. For another, he applied at San Carlos as an Apache instead of properly at Fort McDowell as a Yavapai. Pride played a role, as people had long thought him an Apache, a misimpression he’d done nothing to correct. After all, a wild Apache becoming a doctor in the white man’s world was quite the coup.

Although Montezuma earned income from his medical practice and received small honorariums from speaking engagements, he was never financially secure. His advocacy for Indian causes and openhearted financial help to struggling patients saddled him with unexpected expenses. Self-publishing his newsletter also took money he didn’t have.

In December 1922 an ailing Montezuma, gravely ill with tuberculosis, boarded a train in Chicago for a one-way trip to Fort McDowell. There, on Jan. 31, 1923, the Indian doctor who had successfully assimilated into white society breathed his last atop a blanket spread across the dirt floor of a traditional Yavapai oo-wah brush shelter. He was 56 years old. Montezuma is buried at the Ba Dah Mod Jo Cemetery on the Fort McDowell Indian Nation in central Arizona.

“If I should do anything disgraceful in my life or practice,” he once said, “it would reflect as a wrong to my people.” As a man traversing both white and Indian societies, he lived his life with that principle etched in his heart and mind.

This article was originally published in the February 2018 print edition of Wild West.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.