When Buffalo Bill Cody took his Wild West spectacle on the road 125 years ago, the West was no longer Wild. Cochise was dead. Custer too. Crazy Horse had surrendered to the U.S. Army, and Wild Bill Hickok, Jesse James and Billy the Kid were all six feet under. Railroads cut the travel time between San Francisco and New York from three months to eight days and gave ranchers an easier way to get their cattle to market than a long dusty drive up the Chisholm Trail. Meanwhile, Mr. Montgomery Ward launched an innovative mail-order business that delivered the latest household finery to anyone anywhere.

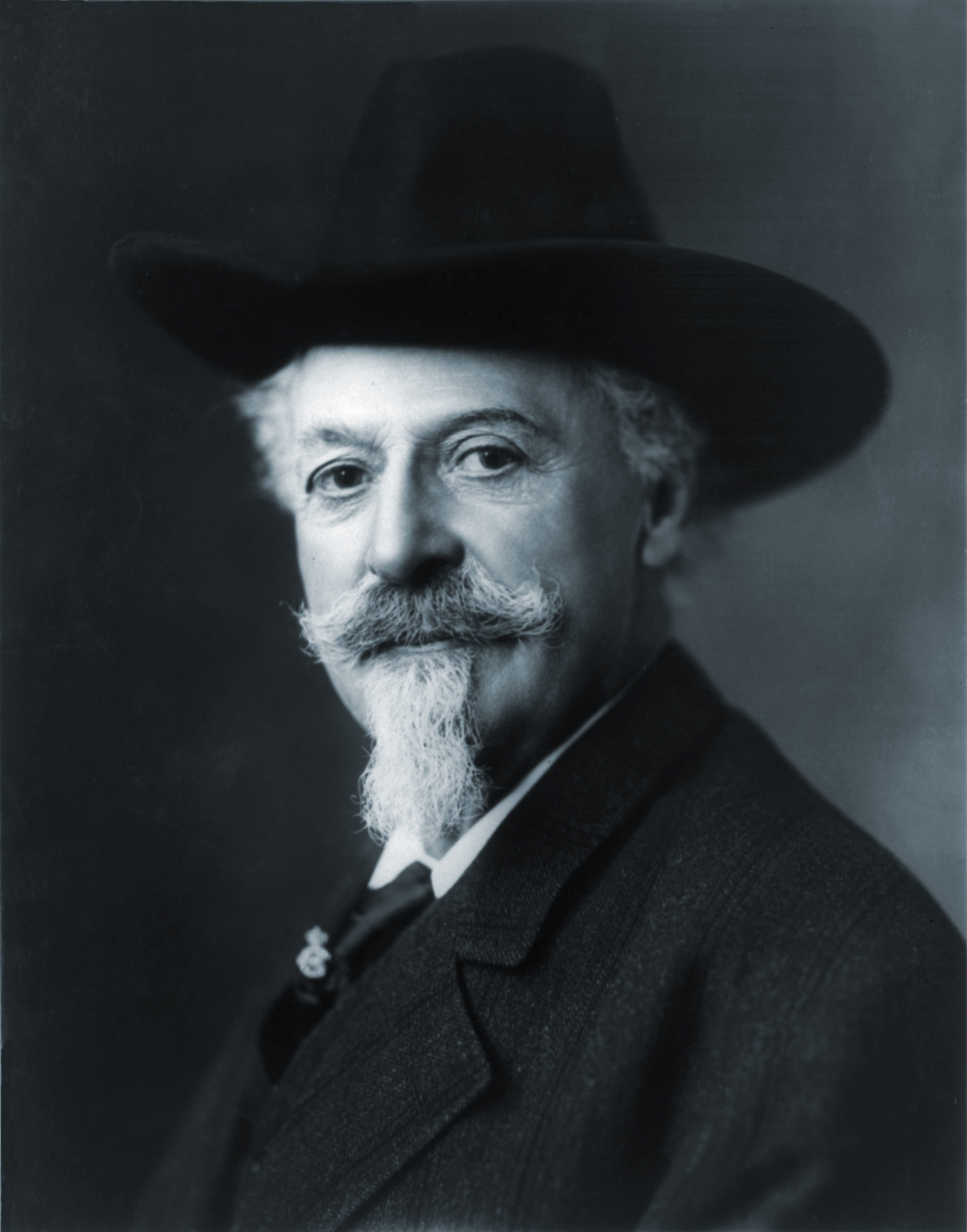

Buffalo Bill’s traveling circus of real-life cowboys and Indians revived the mythical West for audiences that, for the most part, had never experienced it. But the story of glorious conquest was a familiar one since the days of Jamestown and Plymouth: Look beyond your own horizon. Clear the wilderness. Till the prairies. Conquer the natives. It is your Manifest Destiny. The Wild West show spun a tale of national unity and pride that was seared into America’s collective memory. It was the perfect symbol for a country congratulating itself on a job well done, a country that was about to take its place on the global stage.

Never mind that the Indians who were on the receiving end of that quest had been made wards of the U.S. government and wouldn’t be granted citizenship for another half-century. Or that rural folks were now moving to the cities in droves—40 percent of rural townships lost population between 1880 and 1890. Or that millions of southern and eastern European immigrants were pouring into the country, and a widening gap between the haves and have-nots in the New World raised the specter of the kind of violent revolutions that had swept through the Old World in 1848.

In Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, America was a promise just waiting to be fulfilled.