The still-young aviation world began buzzing following an announcement newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst made on October 10, 1910. The media mogul pledged $50,000 to the first pilot to fly across the United States in 30 days or less, in either direction, by October 10, 1911. Hearst said he intended the prize to “encourage the useful development of the aeroplane,” but if he gained publicity for his newspapers, so much the better.

Such a feat would smash all existing records for long-distance, multi-leg flights. Wilbur Wright, for one, was skeptical that it was even possible, feeling that the Wrights’ motor was not up for the task. “I think sixty days ought to be allowed for this reason,” he said. Aviator Glenn Curtiss was more optimistic, saying he didn’t have “the slightest doubt that it will be done.” Louis Blériot, who had become the first person to fly across the English Channel the previous year, was itching to give it a try. “If I had not pledged my word to my wife that I would not fly again, I would certainly compete for this prize and this honor,” he stated.

The list of pilots who said they’d vie for the prize was a who’s who of aviation pioneers. It included Henri Farman, Roland Garros, Harry Atwood, Walter Brookins, Thomas Sopwith and John Moisant. In the end, three pilots, none of them as well-known, made the attempt. They were Calbraith Rodgers, Robert Fowler and James Ward. The obstacles they had to overcome included the lack of powerful, reliable engines; unstable, delicate aircraft easily tossed about by the elements; muddy, rut-filled fields that made takeoffs and landings dangerous, and the lack of navigational instruments. “The man who makes it will be exceptional, physically and intellectually,” Wilbur Wright said. “He will need every atom of courage in his make-up.”

Fowler, 27, was the first to start, departing from San Francisco on September 11, 1911. A native of San Francisco, Fowler had recently completed training at the Wright brothers’ school in Dayton and he flew a Wright biplane. “Fowler expects to cover not more than 3,200 miles, following the northern route of the Southern Pacific Railway,” wrote the San Francisco Examiner. This was the shortest route, but it crossed the Sierra Nevada mountains—a formidable obstacle. On the second day of his attempt, Fowler crashed near Alta, California. He was battered and bruised, and his airplane would need a major rebuild before he could resume his journey eastward.

Ward was the next to start. Born in Denmark in 1886 and raised in Minnesota as Jens Wilson, Ward had changed his name after he moved to Chicago and began racking up speeding tickets while working as a chauffeur. After he graduated from cars to airplanes, he began flying a Curtiss biplane; eventually he became an exhibition pilot for Glenn Curtiss. The Aero Club of America issued him flying license number 52.

Ward took off from New York’s Governors Island on September 13. He was flying a Curtiss biplane powered by a 50-hp engine. “High gusty winds brought him to the grass twice in the course of the day,” reported the New York Sun. “But he wasn’t hurt.”

Calbraith Perry Rodgers began his attempt four days after Ward, with the goal of reaching Pasadena, outside Los Angeles. At 32, he was the oldest of the three contenders. Born in Pittsburgh to an affluent family in 1879, Rodgers contracted scarlet fever at the age of six and suffered significant hearing loss. This ruled out a career in the U.S. Navy, a family tradition. Rodgers later moved to New York and enjoyed racing cars, motorcycles and yachts. He married Mabel Avis Graves in 1906, and the couple later settled in Havre de Grace, Maryland.

In June 1911, Rodgers visited a cousin in Ohio. Lieutenant John Rodgers was one of the first Naval aviators and was stationed at the Wrights’ flying school in Dayton. Cal Rodgers immediately became smitten with flying and signed up for lessons. He made his first solo flight a week later, after only 90 minutes of instruction, bought a Wright Model B and quickly earned aviator’s license number 49.

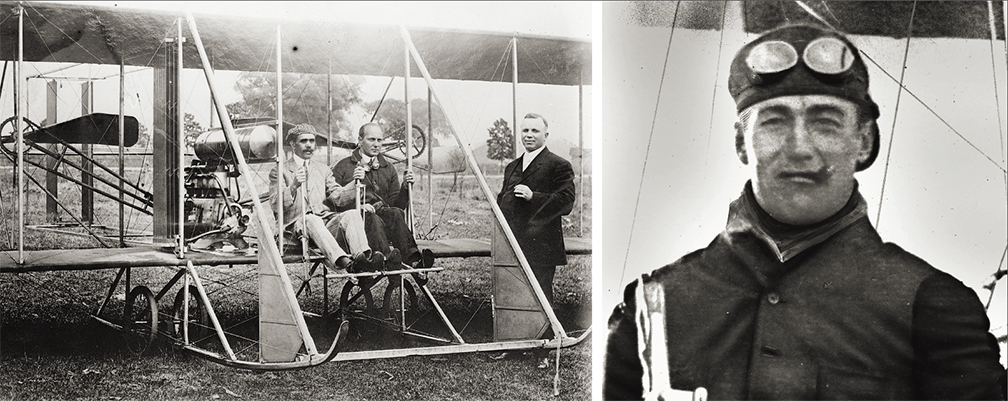

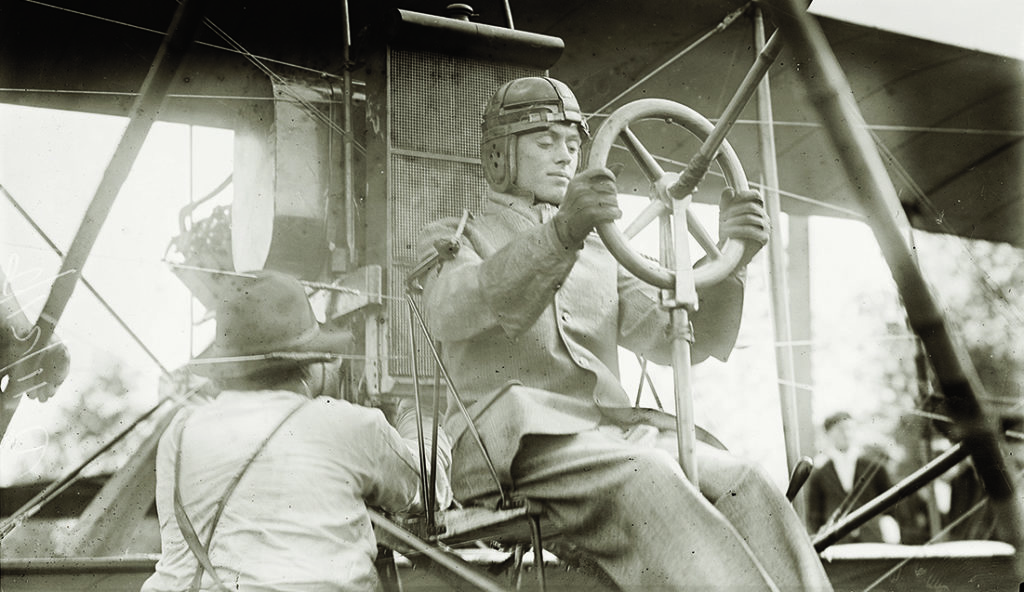

Rodgers was 6 feet 4 inches tall and weighed about 200 pounds, so when he began exhibition flights he made headlines as the world’s largest aviator. He was also a man of few words. He radiated calm and confidence and usually had a cigar clenched between his teeth. At the Chicago International Aviation Meet in August 1911 Rodgers made a name for himself, winning a total of $11,285, $6,875 of it for logging the greatest amount of flying time (27 hours) during the nine-day meet. A few days later, Rodgers took his mother, Maria Rodgers Sweitzer, up in his Model B, most likely the first time a pilot flew his mother as a passenger. “If I were young I’d buy myself an aeroplane and sail thru the air,” Sweitzer said after landing.

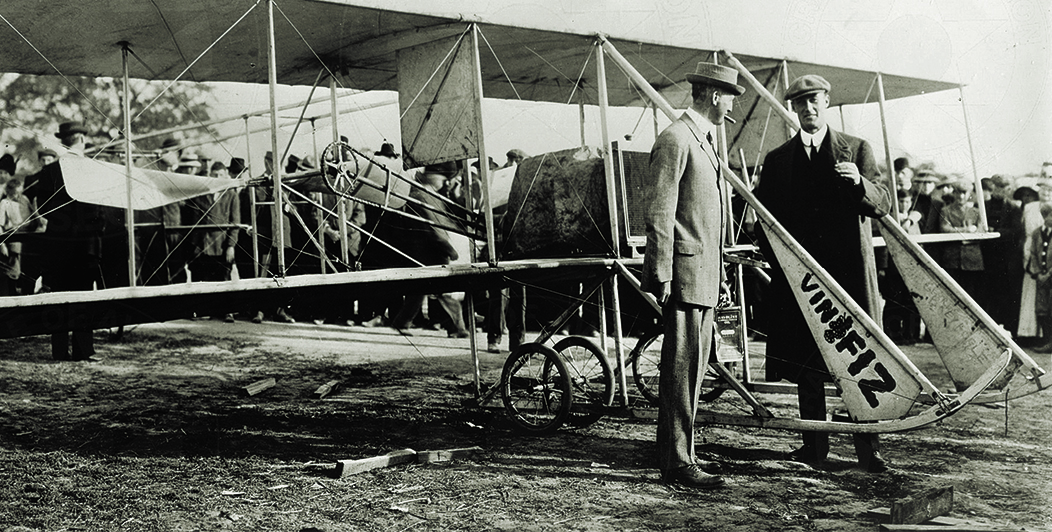

Rodgers persuaded Armour & Company to sponsor his transcontinental attempt. The Chicago-based meat-packing concern had recently branched out by introducing a new soft drink called Vin Fiz, a grape soda. The company agreed to pay Rodgers $5 for every mile he flew east of the Mississippi and $4 for every mile west of the river, where the population was less. Armour provided Rodgers with a Wright EX (for experimental) biplane, a modified Model B that was a little smaller and faster than the original. Rodgers called it the Vin Fiz and had the underside of the lower wing emblazoned with the soft drink’s logo. In addition, Armour provided a three-train railroad caravan to follow Rodgers across the country. The train cars were painted white so Rodgers could spot them from the air, as he planned to use railroad tracks for his navigation system. The “hangar” car contained Rodgers’ Model B and $4,000 worth of spare parts, enough to rebuild the Model EX three times.

The Flyer also carried an automobile so the crew could reach Rodgers when he landed—or crashed—away from the tracks. His mother and wife, who reportedly did not get along, were aboard the train, along with a crew of mechanics (including Charles Taylor, who used to work for the Wrights), a publicity manager and Armour representatives, along with a rotating crew of newspaper reporters.

Rodgers took off from the Sheepshead Bay racetrack in Brooklyn, New York, at 4:24 p.m. on September 17. He would have departed earlier, but the crowd of 2,000 pressed too closely—a scene that would be repeated in town after town. “It was only after the aviator warned the crowd that somebody would get killed if a clear path wasn’t made for the biplane that the crowd backed away,” reported the New York Sun. Rodgers flew 104 miles in 105 minutes, ending the day in Middletown, New York.

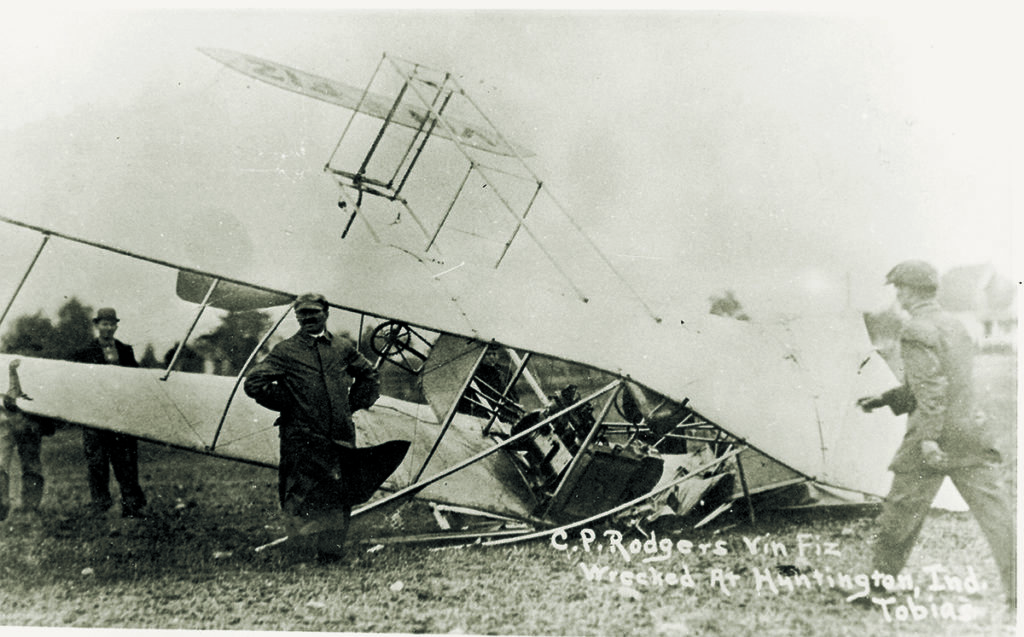

The first crash happened on Rodgers’ second day of travel. “Owing to the dense crowd which packed about his machine and refused to move back, Rodgers was compelled to start in a direction which sent him crashing into a tall tree,” reported the Buffalo Enquirer. “He tried to veer his course but was menaced by telegraph wires and rather than chance electrocution he risked a crash into the trunk of a tree.” Rodgers was knocked unconscious and received a gash on his right temple. The Vin Fiz broke a propeller and had large sections of canvas shredded. “I intend to resume flight just as soon as I can,” Rodgers said. “That cut in my head is painful, but I don’t believe it will prove serious.”

Four days after Rodgers’ crash, on September 22, an engine failure forced Ward to make a hard landing in Addison, New York. Later that day, he announced he’d had enough. “When my engine failed and I was forced to [descend] 1,000 feet to earth here today it was the last straw needed to break the camel’s back,” he said. “I am through.” In the meantime, Fowler found himself stuck in Colfax, California, unable to make it over the Sierra Nevada.

Rodgers and the patched-up Vin Fiz began that day in Hancock, New York. He hoped to reach Binghamton but followed the wrong railroad tracks. He was shocked when he spotted coal mines below him. “I had studied the route enough to know that coal mines did not belong in Binghamton,” he said. He landed and asked the growing crowd if he was in Binghamton. He wasn’t; he was in Scranton, Pennsylvania, off by one state and 60 miles. But the Vin Fiz, the first airplane to visit Scranton, caused a sensation. People signed their names on the fabric and climbed all over the machine. “They liked to work the levers, sit upon the seat, warp the planes and finger the engine,” said Rodgers. “I lost my temper when a man came up with a chisel to punch his monogram on an upright.”

Rodgers crashed again two days later when he collided with a barbed-wire fence on takeoff from a field outside Jamestown, New York. “Now the repairs I need will delay me three days and the man whose fence I hit needs a new one,” he noted.

On October 1, Rodgers reached Huntington, Indiana, after a nerve-wracking flight among thunderstorms. Stuck on the ground by the winds the next day, Rodgers went for a joyride in the caravan’s automobile and continued his streak of bad luck when he hit a ditch and shattered the brake shaft. “That added to the aviator’s gloom, for next to flying, he likes nothing better than buzzing around in his auto,” reported the Huntington Herald.

When he reached Marshall, Missouri, on October 10, Rodgers had flown 1,398 miles. This broke the record of 1,256 miles set by Harry Atwood on a recent St. Louis-to-New York trek. That was the good news. The bad news was that October 10 was the cutoff for the Hearst prize and Rodgers hadn’t even reached his halfway point. Although he no longer had a shot at Hearst’s money, Rodgers remained determined to finish the journey. With the deadline removed, he decided to detour to the south, then fly across Texas, New Mexico and Arizona into California. This route added several hundred miles, but it avoided high mountains.

On October 17, Rodgers ran out of fuel near Pottsboro, Texas, and landed in a field. “He was in a cotton patch and two wide-eyed country lasses stood near the machine gazing in wonder,” reported the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. The young ladies located a couple cans of gas so Rodgers could refuel. “Then the aviator mounted to his seat and the two girls cranked the propellors as gracefully as any mechanician ever could.” The next day he was over Dallas, where a crowd of 4,000 “were beyond the control of the mounted police and patrolman,” reported the paper. “They swarmed over the field, cheering, throwing hats and caps into the air, and seriously interfering with the aviator, whose face could be seen as he peered down and slowly circled the field in spirals.”

Rodgers knew what to do. He headed in one direction, and the crowd followed. Then he quickly changed course, “sailing over the heads at a height of probably seventy-five feet and then coming to earth half a block away.”

As this was happening, Fowler was back in Los Angeles, having given up his attempt to cross the Sierra Nevada mountains. He decided he would follow the same southerly route as Rodgers, but in reverse. That meant the two aviators might cross paths.

On October 19, aviator Eugene Ely—the first man to take off from and land on a ship—died in a crash at an air meet. The news shook Rodgers and the next day he made a careful inspection of the Vin Fiz and discovered that the wires for the elevator and rudder were seriously worn, to the point that they might have failed before he reached his goal of San Antonio, 188 miles away. He made the necessary repairs, but then almost crashed when his engine failed at 3,500 feet. He was able to glide— “volplane,” as it was called back then— for two miles, noting in his log that he “made a perfect landing in the only pasture within forty miles.”

He crashed again on October 25 when taking off from Spofford, Texas. According to his log, “the right propeller struck a little mound of earth the plane swerved, there was a crash and both propellers were splintered. The skids collapsed and the machine swung due north, the left warping wing hitting the ground and crumpling as though it were made of pasteboard.”He crashed the repaired plane again three days later, when he hit a fence as he took off from Sanderson, Texas. He smashed the skids but was soon back in the air. He flew 231 miles that day and landed in Sierra Blanca, Texas—his longest one-day flight. According to newspaper reports, Rodgers attended the bullfights in nearby Cuidad Juárez, Mexico, and “attracted great attention.”

Fowler was getting closer. On October 30, he was approaching the University of Arizona in Tucson when a wind gust blew his biplane into grandstands where hundreds of spectators were waiting. “For a time there was panic, but it was soon quelled when the machine was seen to stop, tangled up in the barb wire fence that surrounds the stands,” according to newspaper reports. Nobody was injured, but Fowler had destroyed the skids of his airplane. He remained in Tucson, waiting for repairs and for the arrival of Rodgers.

Rodgers reached town on November 1. The Tucson Citizen reported, “Hardly had he brought his aeroplane to a stop when his brother-aviator, R. G. Fowler, dashed up in an automobile, sprang out, and grasped his hand with hearty congratulations. ‘Well done, old man; it was a beautiful flight,’ he said.”

Two days later Rodgers crossed the border into California, but his troubles were far from over. Just past Imperial Junction (now Niland), a cylinder blew, wrecking the motor. “Quickly shutting off his gas, the aviator began to volplane, and glided back over the four miles to Imperial Junction, where he made a successful landing near the Southern Pacific station at 11 o’clock,” reported the San Francisco Examiner. Other newspapers wrote that metallic fragments from the blown engine “passed perilously close to Rodgers’ head.”

Engine repaired, Rodgers hoped to finish his journey the next day, but it was not to be. Just past Banning, as Rodgers neared the peaks of the San Bernardino Mountains, the engine began to sputter, forcing Rodgers to land. He discovered that his fuel tank was leaking and he had nearly run out of fuel.

November 5 found Rodgers only 80 miles from Pasadena, his designated end point. But the Vin Fiz was in bad shape, especially the engine, and there was no guarantee it would make the last leg. Rodgers had to land in Pomona for engine repairs but was soon back in the air for the final 30 miles of his flight. In Pasadena, a crowd of 20,000 was waiting for him. As the Vin Fiz touched down, “the crowd was transformed into a maelstrom of aviation-mad people,” reported the Examiner. “Fully 10,000 people rushed madly for the machine. Men stumbled and went down and were carelessly trodden on as the wave of humanity swept on.”

Rodgers had flown 4,231 miles in 49 days, surviving eight crashes (according to his log) and several near crashes after he was forced to glide to earth after his engine quit or ran out of fuel. He averaged 51.59 miles per hour. By the time he reached Pasadena, all that was left of the original Vin Fiz were the rudder and oil-drip plan. And the battered pilot. “No, I don’t feel tired.… It’s easy.… But I don’t believe it can be done in thirty days,” Rodgers said, according to the Los Angeles Times. The paper noted that the pilot, sipping a glass of milk, was a man of few words and that his responses “to the many questions put to him were almost monosyllabic.”

Although he had reached his destination, Rodgers remained determined to fly all the way to the Pacific at Long Beach. “I must go to the surf, and I will do this just as soon as I can get my motor fixed,” he said. He was finally ready on November 12. About 75,000 people gathered in Long Beach, awaiting his arrival. Just past Compton, the Vin Fiz’s engine began to sputter. The Los Angeles Times reported that James Orr, a Compton ranch owner, heard the engine quit. “Then he saw Rodgers lean forward and tug frantically at a lever. The engine seemed to stop dead, the forward end of the planes tilted and an instant later the whole plunged to the ground.”

Orr raced over to untangle the pilot from the wreckage. Rodgers had suffered a concussion, internal injuries and a broken ankle. “Oh, I’ll finish that flight, all right,” he said the next night from his bed as he smoked a cigar.

He made good on that pledge on December 10. Starting near the field where he’d crashed a month earlier, Rodgers took off in the repaired Vin Fiz after a brief delay due to high wind and headed toward Long Beach. “A crowd estimated at 60,000 persons saw the landing, and as the wheels of Rodgers’ machine touched the sands an enthusiastic throng surged on the aviator and the impact of the rush pushed the machine into the waves,” reported the Stockton Evening Mail. Rodgers, still recovering from his injuries, “limped away on crutches which he had carried in the frame [of the Vin Fiz],” reported the Los Angeles Record.

On the other side of the country, Fowler landed in Moncrief Park in Jacksonville, Florida, at 4:45 p.m. on February 12, 1912. He had become the second man to fly across the country and the first to do it west to east. A year later Fowler accomplished another first by flying nonstop across the Isthmus of Panama—the world’s first nonstop transcontinental flight.

Cal Rodgers did not have long to savor his triumph. He started performing exhibition flights from Long Beach in his Model B and he was in the air on April 3 when he flew into a flock of seagulls. Observers saw him fly through the birds and then go into a 45-degree dive. “Rodgers was seen to pull on his lever control and give a startled look backward at his machinery, which evidently had not responded to his will,” reported the Los Angeles Times. One of the seagulls had become wedged between the rudder and tail, making it impossible to control the airplane. “The next instant the horrified spectators saw the biplane continue to drop like a plummet. Straight into the first line of breakers it darted, plunged its nose into the sand, wavered for a second, and then turned over, pinioning Rodgers in the mass of broken wires and framework.” The first doctor to arrive at the crash site stated that the pilot had been killed instantly.

The first person to fly across the United States was buried in Pittsburgh. His airplane, the much-battered Vin Fiz, is on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Steve Wartenberg is a freelance writer based in Columbus, Ohio. A former newspaper reporter, Wartenberg has written several books. For further reading he recommends Cal Rodgers and the Vin Fiz: The First Transcontinental Flight by Eileen Lebow and Higher, Steeper, Faster: The Daredevils Who Conquered the Skies by Lawrence Goldstone.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of Aviation History.