Judges argued whether Sherman Antitrust Act was written as intended

COULD MEMBERS of Congress really have meant what they wrote when they passed the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890? That law’s tough language banning monopolies was clear enough. However, for 20 years federal judges argued as to whether legislators meant their words to be taken at face value, given the sweep of the law’s prohibitions on other aspects of anticompetitive behavior.

In a landmark 1911 ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the dismantling of Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey, THE power player in the American petroleum business. In that case, the justices finally decided that the Sherman Act meant less than a literal reading suggested. This new ruling gave businesses a shield against prosecution for monopolistic behavior on which

(Library of Congress)

enterprises continue to rely. The 8-1 vote on Standard Oil masks just how contentious and divisive the question of how to rein in predatory market dominance by monopolies had been.

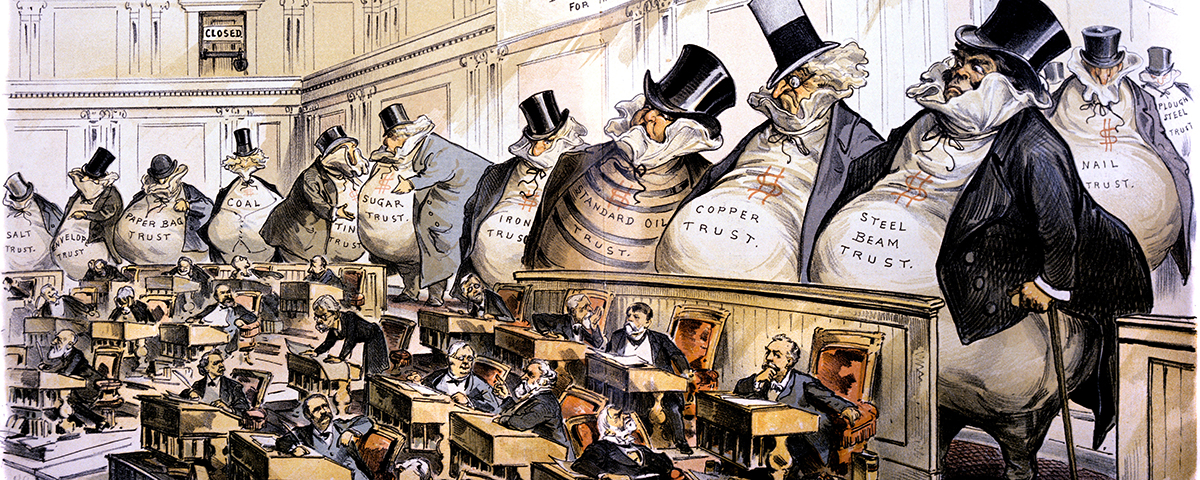

The act—named for its principal author, Senator John Sherman (R-Ohio)—outlawed not only moves intended to create monopolies but also “every contract, combination, or conspiracy in restraint of trade.” That all-

inclusive adjective was the trigger for the judicial debate. “Every” clearly reflected the tenor of the times, which had seen consolidation into trusts in industry after industry. Trusts dominated such sectors as petroleum, sugar, whiskey, tobacco, and lead, and the populace was in an uproar over former competitors’ untrammeled ability to collude and hike prices. In the 1888 election, both parties recognized that unrest and pledged in their platforms to curb the trusts’ power. Taking the White House, Benjamin Harrison used his first message to Congress to ask for action against what he called “dangerous conspiracies.” So widespread was political animus to trusts that Congress passed the Sherman Act—the nation’s first antitrust statute—by a unanimous House vote and with only one “nay” in the Senate.

The problem with that no-exceptions “every” regarding restraint of trade was that if prosecutors and courts acted as though the law meant what it said, commerce on Main Street would grind to a halt. For instance, it is common when selling a retail operation for a seller to promise not to open a competing store across the street. Legally, a clause like that in a sale contract constitutes restraint of trade—as does a contract in which a distributor obtains exclusive rights to its territory.

The issue of applying the law to EVERY contract didn’t come to a head because federal prosecutors had no interest in using the Sherman Act to police day-to-day transactions by small businesses.

But judges, out of desire to know what standard to apply when hearing antitrust prosecutions, debated the statute’s theoretical reach. Some lower court judges felt that they had to act as though the provision applied only to restraints harmful to consumers. Supreme Court justices hotly debated what guidance to give, but a slender controlling majority refused to dilute the law’s strict wording.

The first case in which the Supreme Court interpreted the Sherman Act’s sweeping language came in 1897, in a government action against a railroad trust whose participants agreed to set freight fees at a relatively low rate. The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in St. Louis had thrown out the prosecution, saying that the carriers’ arrangement was reasonable and did not produce exorbitant rates or hurt the public.

But a majority of the high court justices found the appellate court wrong. They declared that the railroads’ deal violated the Sherman Act, “no matter what the intent was on the part of those who signed it,” in the words of Justice Rufus W. Peckham. However, four of the nine justices—led by Edward White—adamantly opposed that logic.

These four insisted that the proper standard was whether a restraint in a business contract was reasonable—the standard that courts had applied before the Sherman Act became the law of the land. Admitting that the act did outlaw “every” such contract, White wrote that to take the law’s language literally “is tantamount to an assertion that the act of Congress is itself unreasonable.”

Repeated in later Peckham decisions, the strict universal reading remained the law of the land. However, lower court judges who had to apply that reading of the Sherman Act grew increasingly unhappy, even when they agreed with the government that a deal being litigated violated the Sherman Act. For instance, William Howard Taft, in his pre-presidential years as a federal appellate judge, acknowledged that any routine business contract restrained trade but argued that such curbs became unlawful only when the restraint “exceeds the necessity presented by the main purpose of the contract.”

When the Supreme Court in 1911 finally switched its position, the court ordered that the phrase “every contract, combination, or conspiracy in restraint of trade” applied only to deals that raised prices, reduced output, or lowered quality. The court adopted White’s position that judges should apply a “rule of reason” in measuring a contract against Sherman Act standards—not so much because lower court judges were pressing them to do so but because the high court’s makeup had changed. White, leader of the rule-of-reason contingent, had been elevated to chief justice, and seven other seats had turned over.

Moreover, Justice White had moved beyond his rather arcane earlier argument that old English law dictated application of the law only to unreasonable restraints of trade. White won over newcomers by positing a more immediate and practical concern: that if Congress could limit reasonable contracts, Congress could impose any limits it wanted on the private accumulation of property.

Of the faction legal historians call “the literalists,” only John M. Harlan, then in the final months of almost 34 years on the court, remained. Harlan was alone in calling the switch to a “rule of reason” a dangerous watering down of the Sherman Act. He delivered a stinging oral dissent in the courtroom, a “bitter invective, which I thought most unseemly,” fellow Justice Charles Evans Hughes wrote in his autobiographical notes.

But the justices saw that antitrusters did not walk away in dismay. Justices palliated that side’s upset by carefully coupling their Sherman Act interpretation, which substantially pruned prosecutors’ ability to sue businesses, with the break-up of the Standard Oil trust into an astonishing 34 separate pieces.

The Standard Oil story began when John D. Rockefeller in 1870 merged what had been three separate refining partnerships. He began buying competing refineries and expanding his company’s presence both by exploring for oil and opening retail outlets. Standard Oil then used its size to muscle railroads into charging the company less than what competitors paid. In 1882, the Rockefeller business was combined with other petroleum operations into the Standard Oil trust. Estimates vary, but by then Standard Oil of New Jersey controlled at least 70 percent of the American petroleum business. Its share was even higher by the time the government, in 1906, sued to dismantle the company.

The Supreme Court had no trouble, even under its new limited view of the Sherman Act’s reach, deciding that putting so many parts of the oil industry into one corporate basket “is an unreasonable and undue restraint of trade….The inference that no attempt to monopolize could have been intended is unwarranted.”

All the justices endorsed breaking up Standard Oil, which led to the creation of six integrated refining companies, each entitled to use the “Standard Oil” brand in a defined territory, plus an assortment of small oil companies, pipeline operators, two transit companies, a chemical company, and even the firm that made Vaseline.

An unintended consequence was that the combined value of shares in the 34 companies created out of Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey soon was double the value of the corresponding Standard Oil shares, making John D. Rockefeller—who owned about 25 percent of the trust—the richest man in the world.