Eons ago, humankind’s first warrior hurled a spear or stone and prayed to an appropriate deity to guide his ballistic weapon to its target. Millennia later, modern-day man applied his genius and appetite for war toward improving his aim, using electric systems to guide weapons — and the vehicles that launched weapons — to often harder targets.

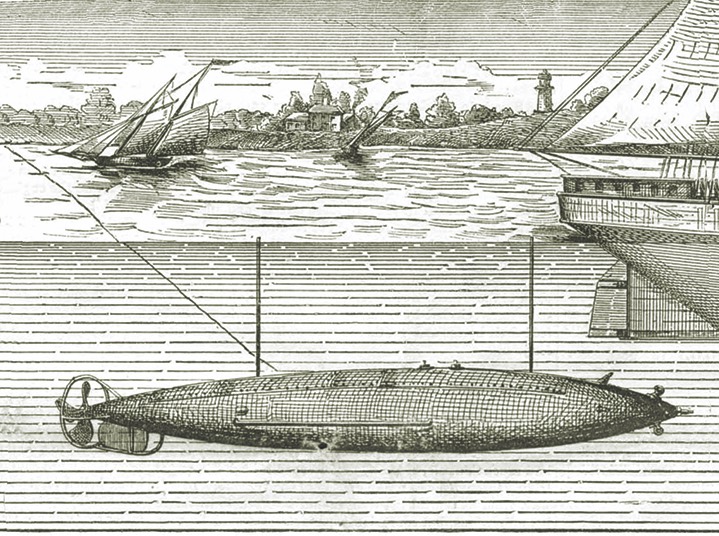

Among the earliest guided weapons were torpedoes, such as that developed by John Louis Lay in 1872. Towed behind a ship until launched, it worked, though not very well.

Powered by compressed carbon dioxide, the innovative Lay torpedo was illustrated in Scientific American in 1873. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

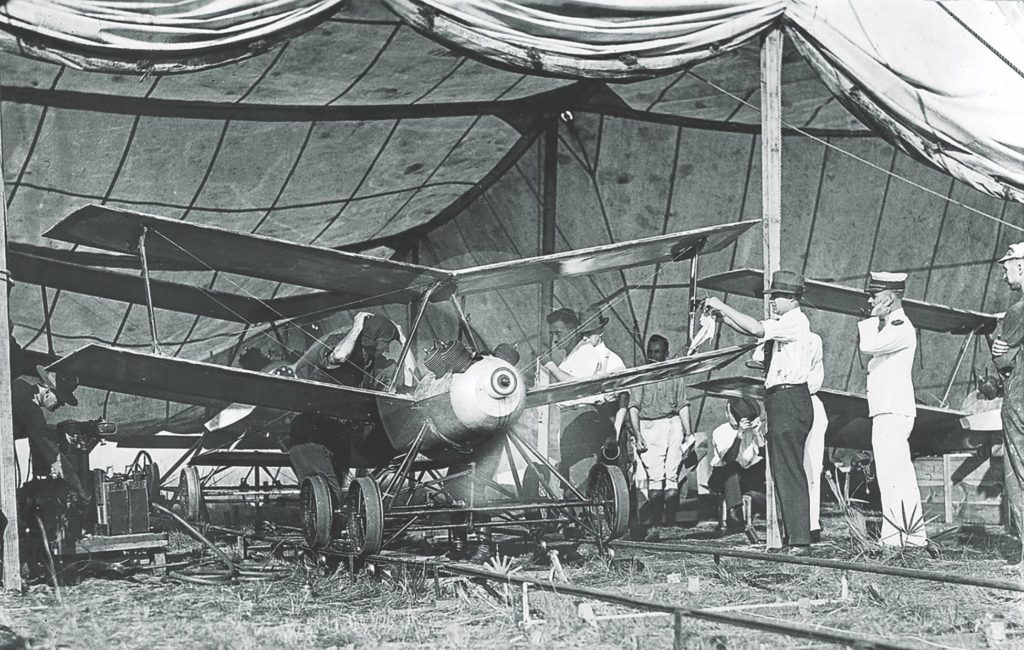

An American ground crew works on the Kettering aerial torpedo (aka the “Bug”) in 1918. (National Museum of the United States Air Force)

This view takes in the open cockpit of a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress modified into a guided bomb for Operation Aphrodite in 1944. Pilots took the aircraft aloft, then bailed out once an escorting plane took remote control. (Imperial War Museums)

German Waffen-SS troops prepare to send a Goliath tracked mine against Soviet positions on the Eastern Front in 1944. (Bundesarchiv)

At war’s end in 1945 Americans examine a captured Mistel—an unmanned Junkers Ju 88G guided bomb affixed beneath a piloted Focke-Wulf Fw 190A. (U.S. Army)

British soldiers of the 321 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Company, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, guide a Wheelbarrow robot to neutralize a suspected car bomb in Northern Ireland. Introduced in 1972, the robot saved countless lives amid the “Troubles.” (Imperial War Museums)

Fortunate survivors view the effects of a buried improvised explosive device—possibly detonated by cell phone—on their Stryker armored fighting vehicle in Iraq in 2007. (U.S. Army)

Controllers in Kandahar guide a General Atomics MQ-1 Predator armed with two AGM-114 Hellfire missiles over southern Afghanistan in 2006. Planners in Reno, Nev., provided mission specifics. (Lt. Col. Leslie Pratt, U.S. Air Force)

A Hezbollah terrorist in Lebanon sets up a Russian-made 9M14 Malyutka (NATO reporting name AT-3 Sagger) wire-guided antitank weapon to bombard Israel in 1996. (Mohamed Zatari, Associated Press)

Operators aboard the guided missile cruiser USS Cape St. George launch a Tomahawk cruise missile from the eastern Mediterranean Sea at a target in Iraq in 2003. (Kenneth Moll/U.S. Navy, Getty Images)

A Royal Marine flies a 4-by-1-inch Black Hornet 2 unmanned aerial vehicle. Developed in 2007 and used in Afghanistan from 2011, the camera-equipped UAV can silently hover for up to 25 minutes on a 1-mile line of sight. (U.K. Ministry of Defence)

A 132-foot Sea Hunter medium-displacement unmanned surface vessel awaits its next test cruise from Naval Base Point Loma, Calif., in 2021. (Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Thomas Gooley, U.S. Navy)

Soon after development of the first practical airplane, the powers involved in World War I worked on guided aerial bombs, such as the gyroscopically controlled Kettering Bug, which took flight in 1918. World War II saw such weapons proliferate on land, sea and air.

But it was the development of computers and the U.S.-owned-and-operated Global Positioning System that ushered in a new era of warfare. The perfection of the unmanned aerial vehicle, or drone, in the 21st century has enabled chairborne controllers to attack targets thousands of miles away.

With such power, however, comes grave responsibility, and all too often a drone-launched missile kills innocent civilians, as happened during the August 2021 fall of Kabul, Afghanistan. Perhaps an even more sobering thought is that the latest generation of remote-control weapons are relatively inexpensive, widely available and fielded by more than 100 armed nations or organizations. The current crop might spark bloodless battles between machines or, perhaps more likely, remorseless remote slaughter.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.