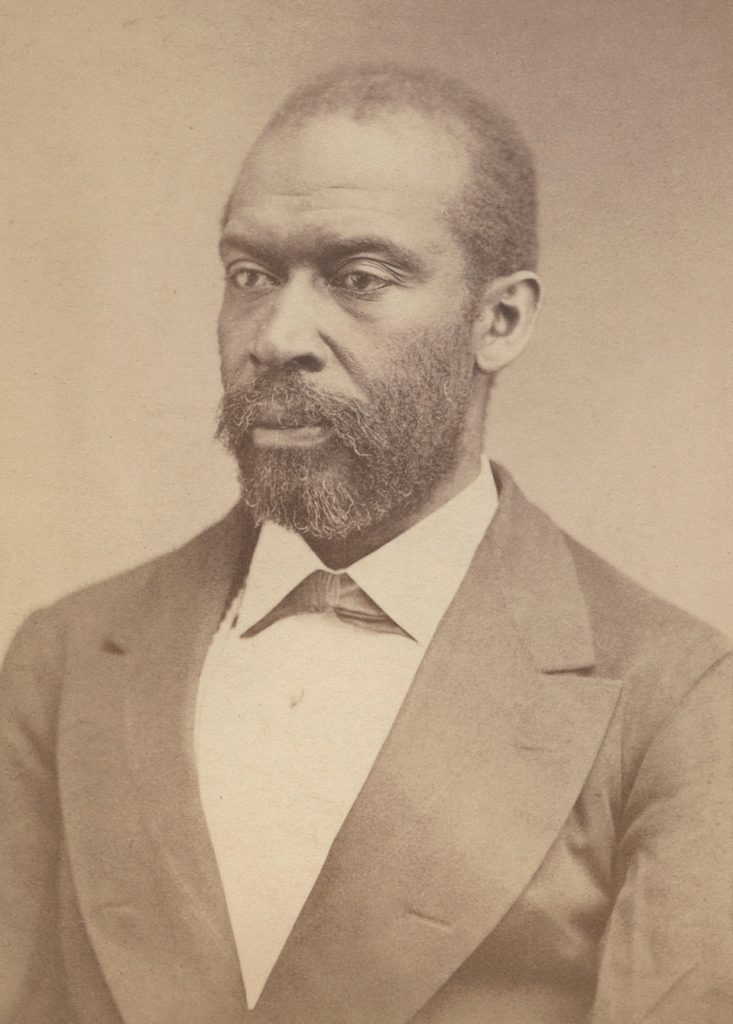

Thomas Morris Chester was born in 1834 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where his parents operated a restaurant that became known as a gathering place for abolitionists. (His mother was born into slavery but had escaped at age 19.) They were successful enough that they could enroll Chester, at age 16, in the Allegheny Institute, a new school near Pittsburgh “for the education of colored Americans in the various branches of Science, Literature, and Ancient and Modern Languages.”

The enactment of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 terrified Chester, who feared that his mother could be kidnapped and hauled back to the South. He felt certain the United States would never allow Blacks—who still did not even have the right to vote in Pennsylvania—to live as equals among Whites. Refusing to submit to such “insolent indignities,” at age 19 he sailed to Liberia, the West African republic founded in the early 1820s to “repatriate” freed enslaved people, with the hope of finishing high school there. But he was so disappointed in the quality of education in Liberia that, after a year or so, he returned to the United States and earned his high school diploma at an academy in Vermont.

Chester made several return trips to Liberia—on one of them he established a newspaper in Monrovia, the capital. But the outbreak of the Civil War in the United States changed everything for him. Although Chester regularly took to the podium to exhort African Americans to emigrate to Liberia, his audiences remained cool to the idea, and public support for the colonization movement waned after President Abraham Lincoln made his Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Weeks later, in an impassioned speech to a capacity audience at Cooper Union in New York City, Chester proclaimed an end to “the dark days of the republic,” saying that it was a time for “rejoicing and exultation,” and concluded by praising “the wise and just administration of Father Abraham.”

In August 1864 the Philadelphia Press hired Chester to report on the Union’s campaign against the Confederate capital of Richmond, making him the first African American to serve as a war correspondent for a major daily newspaper. The same month, using the nom de plume “Rollin,” he filed his first bylined story, “Affairs Among the Colored Troops,” as the Union army camped outside Petersburg, Virginia. He went on to file numerous other dispatches, including one in which he related how the Confederates executed wounded and surrendering black soldiers, and on April 3, 1865, he accompanied the triumphant Union army into Richmond, where he wrote perhaps his most famous story from the speaker’s desk in the Virginia State House.

After the war Chester went to England, where he earned a law degree and went on to serve for two years as Liberia’s diplomatic representative in Europe. Back in the United States, he became the first African American to practice law in Louisiana and later briefly held two minor federal positions before ending his career at the helm of a railroad construction company. He died in 1892 at age 58.

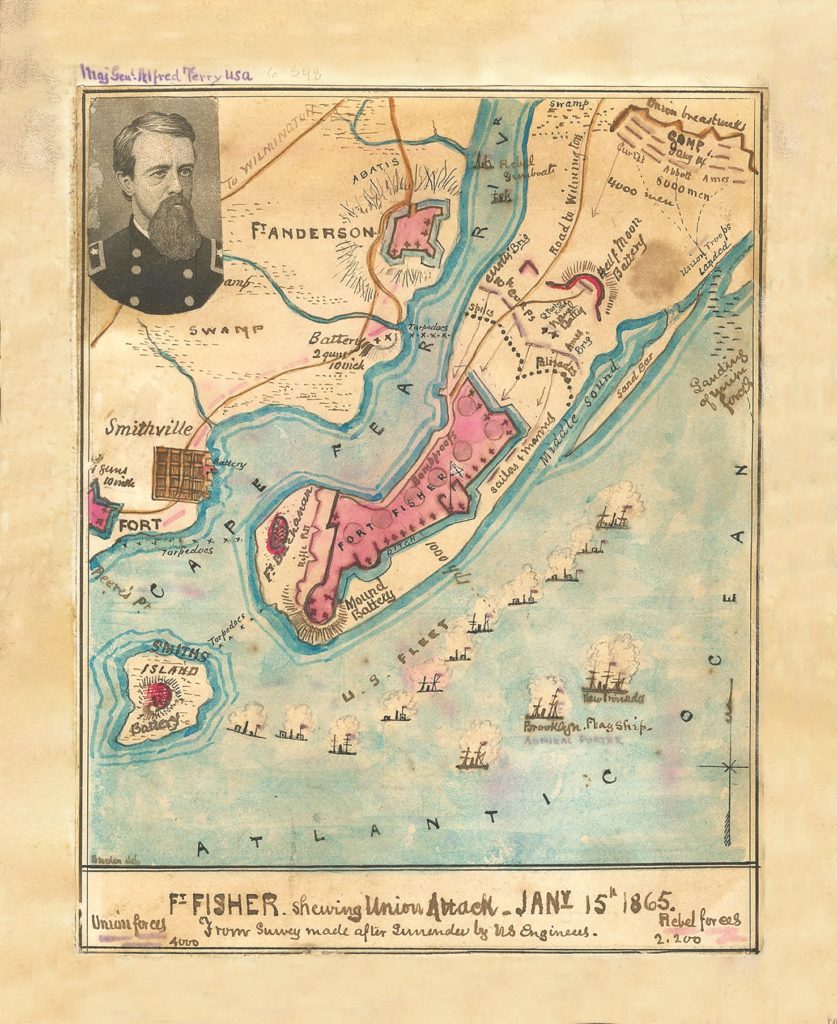

The dispatch that follows—Chester’s account of the Union’s bombardment and amphibious attack on Fort Fisher, in North Carolina, which protected the Confederacy’s last open seaport on the Atlantic Coast—appeared on the front page of the Philadelphia Press on December 30, 1864.

On the evening of the 7th, the 1st Division of the 25th Corps (colored), under Brigadier General [Charles Jackson] Payne, and a division of the 24th Corps, commanded by General [Adelbert] Ames, Major General [Godfrey] Weitzel commanding the whole, broke camp in front of Richmond, and after considerable marching, camped for the night in the vicinity of Point of Rocks. On the following day they all embarked at Bermuda Hundred, and on the succeeding day the transports, about fifty in number, rendezvoused at Fortress Monroe, where they remained until Tuesday morning, the 13th.

Nothing could have exceeded our surprise when we found ourselves going up the Chesapeake Bay, whither the transports were ordered. On our arrival off Matthias’ Point the sealed instructions were to be opened. I was on board the fast steamship Montauk, which was among the first to arrive at the point designated, when we learned that we must put about, and proceed to Cape Henry. No one could see the exact force of this marching up the hill and then down again, but upon the intimation that it might be strategy, all seemed to be satisfied. The fleet was about sixty miles from Washington when we put about to return, passing Fortress Monroe in the night, and anchoring to the westward off Cape Charles. Here we remained until the evening of the 14th, when the steamship Ben Deford, bearing the department flag of General [Benjamin] Butler, and having on board, besides that distinguished officer and staff, General Weitzel and his aides, came down the bay and stood out to sea. The transports followed, and as they passed Cape Henry the sealed orders which were to be read at that point were opened, which indicated that Wilmington was our destination.

On the evening of the 15th the transports arrived off Masonborough Inlet, far out at sea, where we remained, enduring a demoralizing monotony with commendable impatience, until the morning of the 19th, when the Montauk steamed away to Morehead City, N.C., for coal. Excepting the important fact that more cotton is raised now around this place and the neighboring town of Beaufort than previous to the rebellion, no item of interest could be obtained.

On the morning of the 20th we came out from the harbor and sailed for the rendezvous of the fleet. A stiff breeze from the north sprang up, and increased in fury until a young gale was howling over the ocean, continuing through the nights of the 21st and 22d. The usual indications of sea-sickness were manifested by most of those onboard the transport, and the 4th Regiment Colored Troops, which has earned a high reputation for discipline and courage, has never wavered from fear before the fiercest batteries of the enemy, trembled with natural terror during the last and most violent night of the storm, when the winds and waves buffeted our ship about as if it were an egg-shell. The sea was in a perfect tumult of foam and high-reaching billows. The transports and war vessels around us danced from crest to crest, now nestling away down in the foam depths, now tossed high up to descend again with lightning velocity into the valleys that lay between the great ever-shifting water mountains. Of course the fleet became separated, driven hither and thither, till one was lost to the sight of the other—disappearing in the carnival of seething, dashing spray. But in the midst of this elemental discord and before the violence of the tempest had scattered the fleet, it was a pleasing sight to see how bravely the little monitors behaved. Let it be a noteworthy fact that, if the monitors have failed on some occasions to weather a severe gale, they did not on this occasion. They rode over the waves with a seeming consciousness of their power and endurance against the assaults both of man’s ingenuity and the force of the elements. Their sea-going staunchness excited general admiration. Sometimes they would seem to be hurled beneath the water, but they would soon again rise to the surface and shake off the foam like a sturdy Newfoundland coming up from his dive. I think that hereafter there will be more confidence placed to them, not only as efficient war vessels, but also as safe and staunch sailers.

The storm did not, of course, pass us by without inflicting some damage. One of the horses tied on the deck of the Baltic was thrown overboard by the violent rolling and pitching of the vessel, and about thirty-six others, most of which were on the steamer Salvo, were by the same means badly injured. At each lurch they were knocked about till the stalls in which they were placed were broken down. They were then dashed from one side of the ship to the other, until some of them were killed outright and others had their legs broken. The sufferers were in pity thrown overboard.

On the morning of the 23rd our ship’s provisions were at an end, but having a line quartermaster on board, in the person of A. P. Barnes, we were all supplied with Government rations, which consisted of coffee, bacon, and hardtack three times a day, slightly diversified.

About four o’clock on the morning of the 24th we were somewhat startled by an explosion, which shook the very vessel under us. It took place about ten miles distant, in front of Federal Point. I have since learned that the explosion was heard even as far as Newbern, where the people had been expecting this crash. They had been informed by talkative persons connected with the fleet that a great boat was to be blown up to shake down the rebel fortifications, and they must have been waiting for it day and night. This vessel was an iron propeller of about 260 tons, built at Wilmington, and originally owned by a firm (S. & J. T. Flanagan) of [Philadelphia], and was for some time engaged in the Southern coasting trade from New Orleans to Fort Lavacca, Texas. At the outbreak of the war she was taken from her peaceful avocations, and made a gunboat to patrol the Chesapeake and the mouth of the James. She was with Burnside in his attack on the Roanoke Island works, and was somewhat injured in these fights. She went afterwards into the Neuse, and aided Gen. [John G.] Foster considerably when he was cooped up in Washington, N.C. She remained in those waters until the Ordnance Department selected and manipulated her into a monster torpedo.

The explosions of the last decade at Rouen, the effect of the great explosion in England, a short time ago, and even the comparatively small explosions in Connecticut, and at Dupont’s, in Delaware, were carefully considered, and their effects marked. It was concluded that if houses could be shaken down by pigmy gunpowder explosions, solid masonry could be toppled over by the concussion of a thunder rivalling Jove’s. This vessel was therefore taken to Norfolk, and fitted up to receive an immense charge of gunpowder. Her masts were unshipped, her whole hull hollowed out, so to speak, by the removal of all partitions, etc., and made impervious to water. Two funnels were placed in her, and other alterations made so that she would have the precise appearance of a blockade runner. This was done so that when the attack on the rebel forts was about beginning she could rush in as if attempting to escape us, our vessels were to make believe to pursue, and she was to beach immediately under the guns of Fort Fisher. Powder was placed in a bulkhead occupying all the berth-deck, except that near the boilers, a little further forward, and nearer the boilers, a section of the deck and part of the hold were filled. The rest of the hold remained empty, to prevent the force of the explosion from going downward instead of upward and sideways. A house on the spar-deck was covered over closely with tarpaulin, extending to the bow from the boilers, and piled up. The powder was laid in tiers—the first in barrels with the heads taken out, and the rest in bags. The arrangements for firing this tremendous charge were very complete. There was a fuse in each gangway, and one forward near the boilers, and from these a Gomez fuse extended all around the vessel, and terminated at one end in the berth-deck and at the other in the hold. The fuses were those known to military men as “three-clock” fuses. There were also fuses that led from each of the clocks to the points of ending of the other fuses. Each stretch of fuses intersected one another at different points, and were platted together at the intersection.

When the expedition left Fortress Monroe hence, this powder-ship was towed all the way to Beaufort by the Sassacus. On her arrival here she was put under steam and run ashore. Two hundred and fifty tons of powder were aboard her, and, as I have told you, we were suddenly startled by the terrific thunder of her explosion. Little boats could be seen approaching us, and about half way from the ship—five miles—rowing as if for life. They contained the commander of the magazine, Captain [Alexander] Rhind, of the steamer Agawam, Lieut. [Samuel W.] Preston, Engineer [A. T.] Mullen, and Ensign [Douglas] Cassell—devoted men, who had risked their lives to give this novel engine of warfare its proper success.

The explosion was awfully grand to those who were not stunned with surprise at the reverberating roar. Sheets of fire, like the projecting leaves from a pine-apple (pardon the homely simile) shot up like winged flames, bearing in dark, tangled chaos black smoke and debris of the vessel. The concussion seemed to come over the water like a hurricane. The sea broke into great majestic swells, heavy even at our distance, considering that they were the outer circles rolling out from a centre ten miles away. The vessel was a great shell. Her iron hull was disrupted as if it was made of tissue paper, and the broken fragments, small almost to diminutiveness, went whistling through the air with the speed of the lightning, and a million of tapering columns shot up from the water far and wide, falling back gently and in graceful curves when the power that reared them into sight had ceased to exist. Up went the black column, like a great magic funnel, widening as it rose, until it covered the whole sky, and was carried away and dissipated on the air currents that wafted it towards Wilmington. It was to that city the baptism of sulphur fumes that heralds what will come sooner or later—the baptism of fire. Although the vessel was close—not more than two hundred and fifty yards away—it is to be questioned whether, after all, the explosion had the effect that was expected. The fort, by subsequent developments, seems to have been but little injured. The intention was, however, to load the vessel with five hundred tons of powder, but as she would hold but two hundred and fifty, that quantity was, of course, all that was used.

About eight o’clock it was evident that active measures would soon begin. I looked hurriedly around for the transports, freighted with Union defenders, but only three were present—the Baltic, the Montauk, and the Victor—the last one having no troops on board. There were fifty-eight vessels of-war and six iron-clads in the grand fleet of Admiral [David Dixon] Porter, and some twenty-one transports—the largest naval force ever concentrated against any point upon the continent. The vessels-of-war got under way about 8 A.M., and stood in for Federal Point, on the right bank of Cape Fear river. It is hardly possible to conceive of a much grander sight than the advance of this fleet in the three lines of battle which you have no doubt already described, as the description was forwarded. The stars and stripes waved proudly from each peak, as each ship gradually neared the land. When a short distance from Federal Point the ironsides and monitors steamed ahead, and bore down upon the enemy, while the wooden vessels followed close after without having taken the precaution of sending down their spars, customary before going into action.

About one o’clock, a shot from one of our ironclads at Fort Fisher is the signal for the beginning of the action, and at intervals, which under the circumstances seem protracted, another and another follows—each succeeding its predecessor in more rapid succession—until one of the grandest naval conflicts of American history is opened. About half of the fleet was soon engaged, and the terrible roar of artillery seemed to be beyond endurance; but when they all participated, the thundering from the fleet intermingled with that from the heavy guns of the enemy, immense columns of white smoke brooded over the water, fringed and colored with bright yellow flame. Now and then the flame seemed to come forth in bright sheets, and cover the water as if with a fiery pall. Reader, imagine all this, so grand, so confusing, so blinding to the eye, presented to you at the same time that the ear was tingled and tortured, not exactly with that thunder which “leaped from peak to peak, the rattling crags among,” [quoting Lord Byron] but that which came out sharp and terrible from the yawning throats of a thousand of those terrible engines of modern war. Then, amid all this splendid panorama of death and this crashing thunder, could be heard the screaming of the great shells as they leaped through the air back and forward from fort to ships and ships to fort. The rebel fire was one of much precision, and some of their immense shells exploded over our vessels with great accuracy. The united concert of belching artillery seemed almost unbroken for hours. The fleet continued to pour into the forts, Fisher and Caswell, showers of shot and shell, until it seemed that they would be buried beneath the fragments of these missiles.

About half-past two o’clock the Montauk stood in close enough to afford a distinct view of the rebel colors, amid the clouds of almost unbroken smoke, upon Fisher, which is nearly as strong as Fortress Monroe. The soldiers pointed them out to me enthusiastically, with a wish that they might soon be sent to lower them. At a quarter of four o’clock a dark smoke arose from the enemy’s works. Fifteen minutes later an immense conflagration was distinctly seen, which indicated that the barracks in Fort Fisher were on fire.

At this sight it was difficult to restrain the enthusiasm of the troops onboard, and prevent them from lustily cheering. If they had, our transport would probably have drawn the fire of the enemy. Such expressions as “get out, Johnny,” “isn’t it too hot for you,” and others of similar import were freely indulged in. No words could adequately express the terrible bombardment at this juncture, or give an impression commensurate with the scene. As night lowered, rendering more distinct the meteoric flash of flying shells, the cannonading gradually ceased, until every gun was quiet.

About a half an hour before the action ended, there was but one of the gunboats that hauled off, or gave evidence of being injured. It had bursted one of its guns, killing and wounding several of the crew. Shortly after, another was towed away, but not until after the engagement was over. Thus ended the first assault on Wilmington.

Neither Generals Butler nor Weitzel were present during the action, but were detained in the harbor of Beaufort, with the rest of the transports, by the severe storm, excepting those that had put to sea for safety. Late in the afternoon, General Butler’s boat hove in sight, and in the course of the night all the fleet withdrew about ten miles to the sea.

Such was our Christmas Eve. We retired to rest thinking of the probable injuries sustained by the fleet, and the condition of the forts. We thought, too, of the loved ones at home, wondering whether their Christmas would be as happy as ours promised to be glorious. MHQ

[hr]

This article appears in the Autumn 2020 issue (Vol. 33, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Classic Dispatches | Explosion of the Monster Torpedo

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!