In early May the southern Scottish day lasts nearly 16 hours. In 1756, a young man from Virginia used that long seasonal stretch of daylight to traverse Scotland from Port Glasgow in the west to Edinburgh in the east. Jamie Montgomery was anxious to make Scotland his home; Britain offered freedom that Virginia denied him. That year Montgomery was one of hundreds, perhaps thousands of enslaved African Americans who were fleeing their British masters but one of the few, if not the only, to do so in Scotland.

Montgomery’s native Virginia, the most densely populated of Britain’s American colonies, counted almost twice as many residents as Massachusetts, next largest among the Crown’s New World holdings. Between 1700 and 1755 Virginia and Maryland had imported more than 140,000 enslaved Africans to work on tobacco plantations, constituting almost 90 percent of the enslaved Africans brought into the region between 1619 and 1809. Supplementing the influx from Africa was a steadily rising birth rate among enslaved women.

The Virginia tobacco industry began spreading west toward the Appalachian Mountains. In about 1740, Joseph Hawkins established a plantation in newly founded Spotsylvania County. Hawkins’s subsequent prosperity led officials to refer to him in their records as a “gentleman” captaining a mounted militia. When Hawkins died in 1770, he owned at least 80 enslaved people.

In liquidating his father’s estate, Hawkins’s son posthumously advertised those individuals for sale in the Virginia Gazette. All had outlived a fellow bondsman who had experienced an extraordinary journey involving trans-Atlantic travel, life in a foreign land, and an epic court fight. That man’s name was Jamie Montgomery.

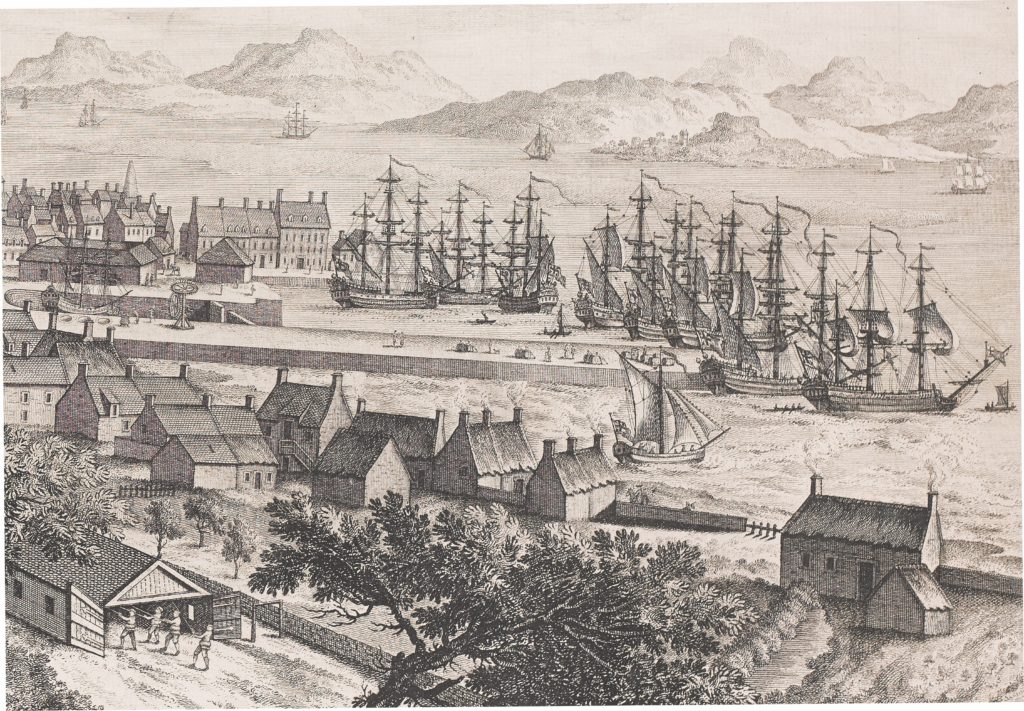

Tobacco planters in central and western Virginia found it difficult and expensive to purchase goods from and send crops back to ports on the Atlantic coast. Capitalizing on this circumstance, Scottish merchants and factors—business agents—stepped in, establishing towns upriver from Chesapeake Bay and developing a near-monopoly on the Virginia tobacco trade. By 1762 more than half the American tobacco reaching Britain did so by way of Scotland. Of Scottish imports, sotweed made up 40 percent, almost all of it through Glasgow and allied ports on the River Clyde.

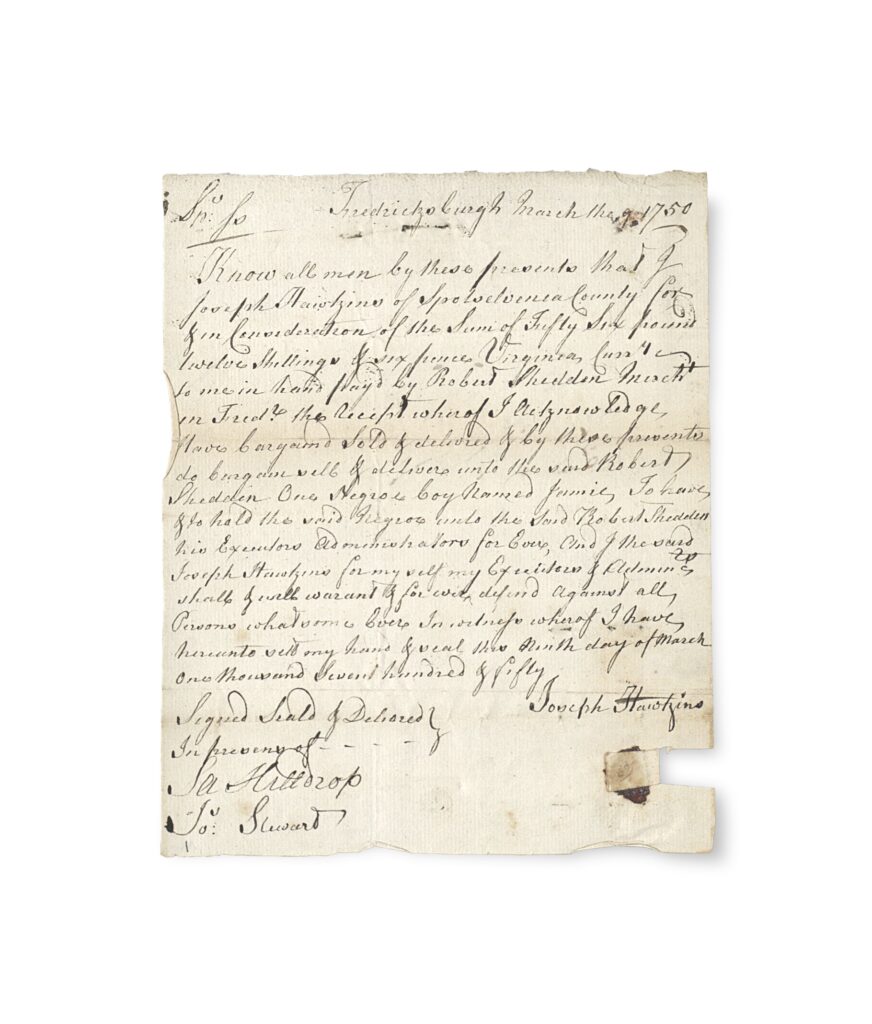

A few Scottish trading houses had offices in Spotsylvania County’s seat, a Rappahannock River town called Fredericksburg. Joseph Hawkins frequently visited on business. On March 9, 1750, in Fredericksburg, Hawkins sold “One Negro Boy named Jamie” to Scottish merchant Robert Shedden. The price was £56, 12 shillings, and five pence in colonial currency.

No record of Jamie Montgomery’s sale exists in Virginia; his change of ownership and other official mentions exist only in the original bill of sale and in Scottish documents held by the National Archives in Edinburgh. Jamie’s mother likely belonged to Hawkins. The youth—when Shedden bought him, he would have been about 16—had grown up in an extensive community of enslaved Africans working Hawkins’s plantations. Few had two names; in Virginia, owners used only a first name to refer to slaves being purchased, sold, or otherwise mentioned in contracts, inventories, and other records. The owner’s name might be used in the possessive, as in “Robert Shedden’s Jamie.”

Robert Shedden was the second son of John and Margaret Shedden of the southwest Scottish county of Ayrshire. In coming to Virginia, Robert was following in the footsteps of his older brother, Matthew. The elder Sheddens, who had a third son, James, owned Marsheland, a property in the parish of Beith. Robert was one of many Scottish sojourners seeking their fortunes working for merchant and trading houses in Britain’s Chesapeake and Caribbean colonies. Shedden was hustling at the heart of the expanding western Virginia tobacco trade, interacting with Glaswegian traders like John Murdoch, William Crawford Jr., and Andrew Cochrane. He later described himself as a “Merchant in Glasgow.”

Successful Scottish merchants commonly purchased enslaved people to do the heavy lifting at their facilities. Shedden had in mind another use for Jamie. In western Virginia, white artisans charged premium prices for their services. Planters eagerly sought enslaved tradesmen with top-flight skills who could handle those tasks or be rented out to neighbors. Slaves expert at joinery, blacksmithing, and other skills valued in the colonies brought significantly more than enslaved laborers with only rudimentary training or no skills. Shedden planned to take the young black man to Scotland and apprentice him to his brother-in-law, who was a joiner, or carpenter. Once Jamie had learned a trade, Shedden would bring him back to Virginia and resell him to Hawkins at a profit.

The would-be carpenter was going to a place where his owner had deep roots. Robert Shedden’s younger sister Elizabeth and her husband Robert Morrice, the joiner to whom Jamie was to be apprenticed, also lived in Beith, whose several hundred souls perched midway between Paisley and Ardrossan.

Jamie arrived at Beith in 1750, moved into the Morrices’ home, and began to learn carpentry. Apprentices abounded in the village, home to masons, sadlers, cobblers, smiths, coopers, and other joiners. Most artisans had apprentices of their own. Jamie probably was Beith’s only dark-skinned resident, but 18th-century Britain’s population included no few people of African descent, especially in London, Bristol, Liverpool, Lancaster, Glasgow, and other cities that were entwined in the Atlantic trade. Many planters, merchants, ships’ officers, doctors, and even clergymen returned from the Americas with slaves, often installing their human chattel at rural homes and estates.

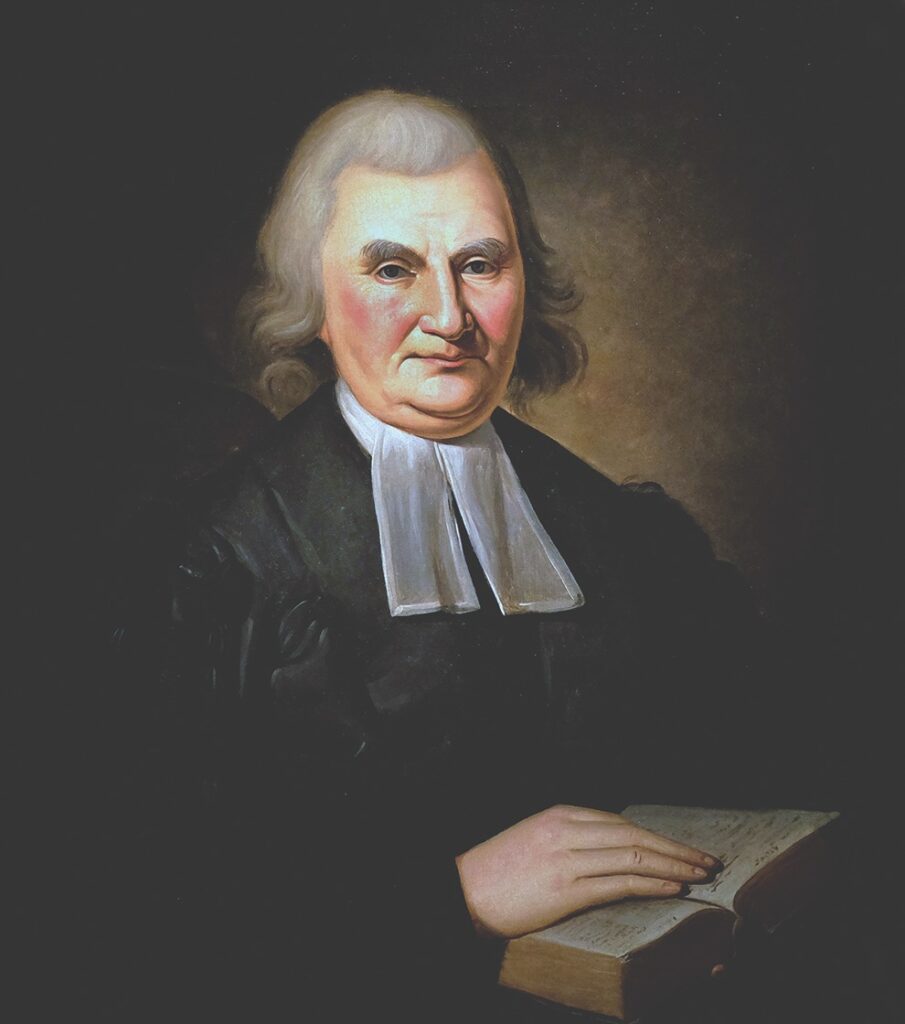

Shedden paid Robert Morrice £40 to cover Jamie’s apprenticeship plus two shillings weekly for his bed, board, and clothing. The training arrangement’s particulars are unclear. Morrice likely had multiple apprentices living communally with his family. Jamie probably had not been a regular churchgoer—Virginia at that time had fewer than 100 clergymen—but Scottish law required attendance at religious services. The Morrices belonged to a Presbyterian congregation John Witherspoon had pastored since 1745, his first assignment out of seminary. Undergoing religious instruction with Witherspoon, Jamie got to know the preacher’s wife, Elizabeth, and their children.

Witherspoon baptized the black apprentice, and in 1756, two years into Jamie’s apprenticeship, gave his student a certificate, sometimes issued by ministers to parishioners who were relocating as a kind of sectarian passport. The certificate, which testified to Jamie’s good Christian conduct, marked the first time anyone had identified him by a last name: Montgomery, Mrs. Witherspoon’s family name.

Shedden, fortune in hand, returned to Scotland in 1752. He bought Morrisill, an estate near Beith, married Elizabeth Simson, and ended Jamie’s apprenticeship—in effect, reclaiming his property, and spitefully. Shedden assigned Jamie a new given name, “Shanker,” a derogatory term for a beast of burden, and for four years put him to work, Jamie later recalled, “in the most slavish and servile business, his only occupation being the sawing of wood, and other laborious works, which requiring neither skill nor ingenuity, but sinews and strength, were therefore judged proper for a Person of [his] complexion, and of his unusual strength and vigour.”

In May 1756, Matthew Shedden was to sail from Glasgow back to his business in Virginia. Robert Shedden thought this a propitious time to send “Shanker” home for resale to Joseph Hawkins. According to later testimony by Robert Shedden, the young slave, eager to reunite with his family, willingly set off from Ayrshire for Port Glasgow, there to board a ship bound for Virginia under Matthew Shedden’s watchful eye.

In subsequent testimony of his own, “Shanker” told a different story—namely, that Robert and James Shedden, aided by two other men, yanked him from bed at Morrisill, bound his hands, and dragged him behind a horse the 15 miles from Beith to Port Glasgow, “not upon the King’s high way, but thro’ muirs or lonely places, and other by-roads,” presumably to avoid being seen. At Port Glasgow, the ship was not yet boarding passengers. At the home of a butcher he knew, Shedden imprisoned “Shanker” under guard. A day passed. Persuading his captors to let him walk the quay “for the recovery of his health,” the young man bolted. He made for Edinburgh, 60 miles east.

Robert Shedden immediately posted advertisements seeking Jamie’s recapture and return in the Glasgow and Edinburgh papers.

A May 4, 1756 Edinburgh Evening Courant notice offered a detailed portrait: “RUN Away from the Subscriber, living near Beith, Shire of Ayr, ONE NEGRO MAN, aged about 22 years, five feet and a half high or thereby. He is a Virginian born Slave, speaks pretty good English; he has been five years in this country, and has served sometimes with a joiner; he has a deep Scare above one of his eyes, occasioned by a stroke of a horse; he also has got with him a Certificate, which calls him Jamie Montgomerie, signed, John Witherspoone Minister. Whoever takes up the said Run-away, and brings him home, or secures him, and gets notice to his master, shall have two guineas reward, besides all other charges paid by me—ROB. SHEDDEN”

By whatever means, Jamie/Shanker made it to Edinburgh, where he hired on as a journeyman with a joinery owned by Peter Wright. He parlayed the certificate from Witherspoon into membership with a Presbyterian congregation. However, a court official lured by that two-guinea reward ran him to ground. At the bottom of Shedden’s original Virginia bill of sale appears an addendum by one John Braidwood, officer of the Edinburgh Baillie Court, named for the magistrates who presided over that institution. In his explanatory note, Braidwood acknowledges receipt on May 13, 1756, of two guineas paid him “for apprehending one Negro Black boy named James Montgomerie” and lodging his captive in Edinburgh’s Tolbooth jail. Apparently, Braidwood, using the information in Shedden’s advertisement, had tracked Jamie to Wright’s joinery and there snatched him.

The Edinburgh magistrates were holding Jamie Montgomery in custody at the notoriously pestilential Tolbooth when Robert Shedden petitioned for his property’s return. The magistrates allowed Robert Gray, the court’s procurator fiscal, or public prosecutor, to represent Montgomery. Responding to Shedden’s petition, Gray asked, “Upon what principle can the pursuer pretend that Jamie Montgomery is a slave?” Details of the resulting case appear in documents filed by Montgomery and Shedden.

Shedden was one of many slave owners in 1750s Scotland, which had little interest in condemning slavery or the slave trade. But in the notices he published trying to recapture Jamie, Shedden chronicled his slave’s acclimatization to Scottish life: he had lived there five years, spoke English, had apprenticed with a joiner, and been decreed by a prelate a Christian in a certificate “which calls him Jamie Montgomery.” Trying to subjugate the young bondsman, Shedden had taken away even his name, which in its reference to a benefactor’s wife’s family implied ties to Scotland.

Another point of contention was Witherspoon’s baptism of Jamie and the certificate he had given the apprentice. Jamie had “got it into his Head, that by being baptized he would become free,” Shedden testified, telling the court he had opposed that baptism because of “the Fancies of Freedom which it might instill into his Slave.” Reverend Witherspoon, Shedden claimed, had told Jamie “over and over again” that baptism “by no means freed him from his Servitude.”

By giving Montgomery such a certificate, Witherspoon, intentionally or not, had reinforced Montgomery’s sense that he was more than an enslaved piece of property—as Shedden maintained, asserting that to buy Montgomery he had “paid £56 Virginia Currency” as well as laying out “considerable Sums for his Apprentice Fee, his Board, Clothing, and the Expence of recovering him, &c.” Montgomery was not entitled to the legal status implicit in the principle of Habeus Corpus, “for by Magna Charta only a Freeman is intitled thereto,” Shedden said.

Jamie Montgomery died seeking freedom, succumbing to disease in the Tolbooth. Twelve years later the Court of Session in Edinburgh ruled that slave owner John Wedderburn, who while in America had bought an enslaved man, Joseph Knight, and brought him to Scotland, had no right to force Knight back into slavery in the Americas—a precedent that all but outlawed slavery in Scotland. As Jamie Montgomery had, Joseph Knight had been baptized in Scotland, where he married Annie Thompson, a white servant, and found freedom.

In the 1760s, Reverend John Witherspoon relocated to the American colonies. He became president of the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University. A well-respected intellectual, Witherspoon tutored James Madison and represented New Jersey at the Second Continental Congress, where he signed the Declaration of Independence. He also became a slave owner, a practice he enthusiastically defended against Quaker attempts to abolish slavery in New Jersey in the 1780s and 1790s.