Besides making crops portable, cocktails like slings, flips, punch, and bounce were healthier than water

Americans have been mixing and downing fancy alcoholic concoctions—and writing about the experience—at least since 1803. On April 28 of that year, the Farmer’s Cabinet, an Amherst, New Hampshire, newspaper, featured a comic story about a “lounger” that included the comment “Drank a glass of cocktail—excellent for the head.” Within a few decades, any American tavern worth its rail was offering a variety of mixed drinks, many with intriguing names such as “stone fence” and “Knickerbocker,” not to mention a plethora of slings, flips, juleps, smashes, and cobblers. Most of these have drifted into obsolescence, but before they did they established an American cocktail tradition.

Cocktails came naturally to a people inclined to crooking the elbow. Inheriting European habits, most early Americans avoided water, not only out of fear of pollution but also a conviction that drinking alcoholic beverages was more healthful. Brewing purified the water used in the process, and the result kept fresh longer than barreled water. The Pilgrims and other colonists packed their ships’ holds with beer and distilled spirits that would last through the voyage and, once settled, began brewing with local ingredients. To preserve the fruits of their labor, orchard growers made hard cider.

Colonial mores scorned public drunkenness but considered regular daily alcohol intake normal and healthy. Before breakfast, a typical adult swallowed a couple of throat-clearing “phlegm cutters” made with rum, brandy, or other spirits. Consumption continued throughout the day, with even children washing down meals by drinking relatively low-alcohol beer and cider. Employers provided farmhands and laborers with daily alcohol rations to loosen sore muscles and lubricate tasks. House and barn raisings, funerals, and other community events called for ample alcoholic refreshment. Women considered it coarse to slug down shots of hard spirits, preferring alcohol-based cordials and medicinal elixirs.

Colonial America favored rum, usually diluted with water but also as bumbo, a mixture of rum, sugar, water, and nutmeg; calibogus (rum and beer); cherry bounce (rum and cherry juice); and stone fence (rum and cider). American colonials imported rum from the British West Indies, part of the “triangle trade” that transported slaves from Africa to the British sugar islands and shipped colonial products to Britain and the American colonies. Americans also made domestic rum from imported West Indian molasses; the first American rum distillery opened in Boston in 1700. By mid-century Boston had 30 rum distilleries, another 30 dotted Newport, Rhode Island, and others stood across New England.

Most 18th-century mixed drinks were punches—blends of spirits with fruit juices and even milk, flavored with sugar and spices and, varying by season, served hot or cold from a large bowl, usually to a convivial crowd. The active ingredient might be brandy, cognac, gin, whiskey, wine, rum, sherry, or port, with rum and whiskey the preferred active ingredients. Members of the Schuylkill Fishing Company of

Pennsylvania, a group of anglers who in 1732 formed the first social club in the colonies, were renowned for Fish-House Punch, which got its kick from rum, peach brandy, and cognac.

Most towns had at least one tavern. Besides providing travelers with lodging and meals, these “third places” offered locals a hospitable spot at which to gather, whether socially or for a collective purpose, such as political meetings, at which the back-and-forth benefited from the barman’s ministrations. Ambitious office-seekers hoping to be elected to colonial assemblies such as the Virginia House of Burgesses hosted barbecues and other events featuring beer and spirits, a practice known as “swilling the planters with bumbo.”

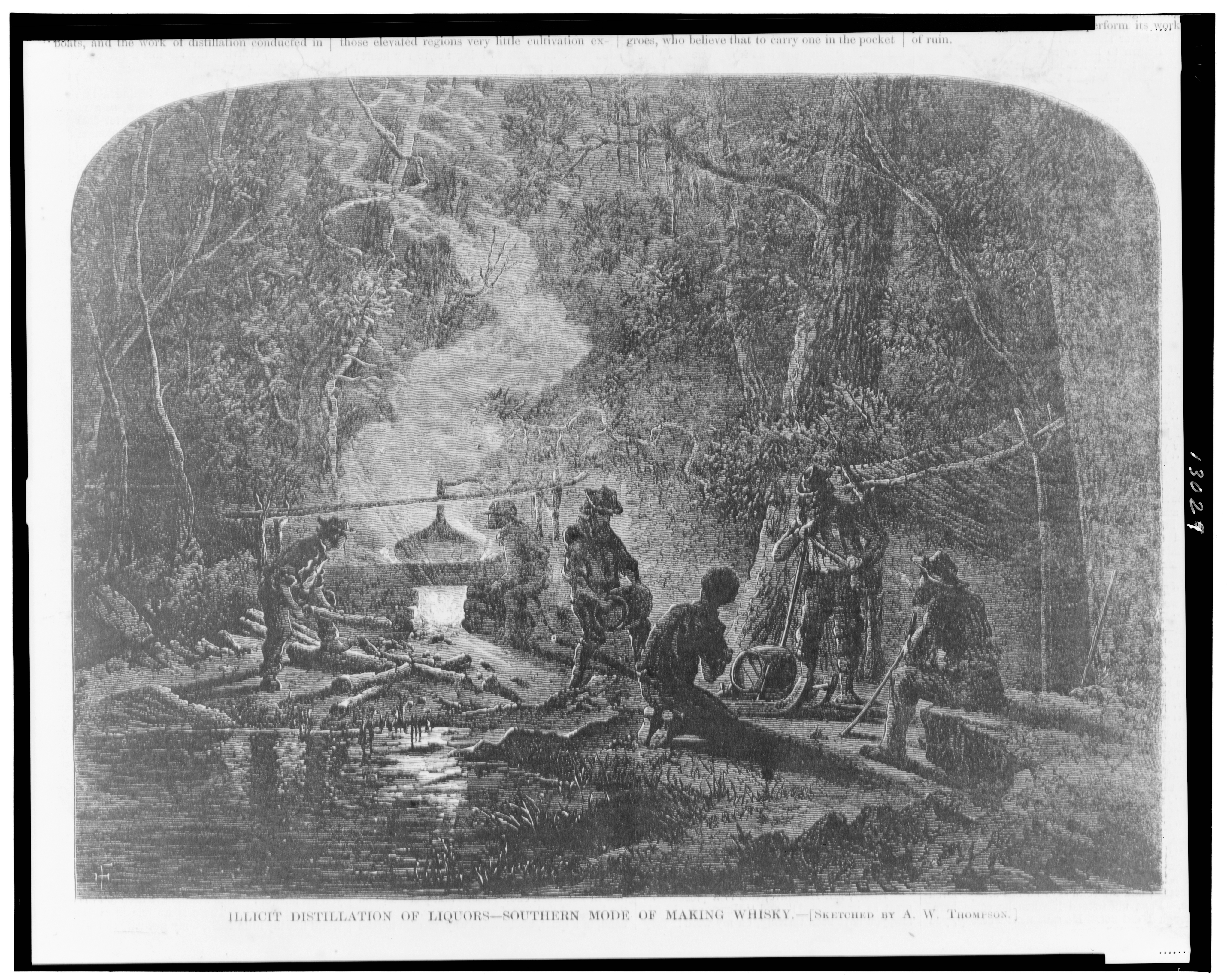

Whiskey was popular as a way to commodify grain—compact, highly prized, easily transported. Beer and cider in wooden kegs kept for many weeks—barrels of beer made it across the ocean from England to North America and still were potable—but distilled spirits kept even longer. Because liquor was more potent, settlers transporting it to isolated rural areas didn’t need to carry as much. If out of range of store-bought booze, hinterlanders had the option of setting up a still and boiling mash themselves, using surplus grain.

Domestic distilling blossomed amid the Revolutionary War, which severely curtailed rum and molasses imports. Wheat and rye had fans among distillers, but most Americans of the era made whiskey from corn. During the Revolution, the Continental Army allotted soldiers four ounces of spirits a day, with extra drink distributed before battles and at other times of profound need. By the 1780s, corn whiskey had far outpaced rum as the staple American spirit. Bourbon County, Virginia, later the fifth county of the new state of Kentucky, produced a prodigious amount of corn whiskey, leading to the designation “bourbon.” In 1797, former president George Washington built a distillery on the grounds of his home at Mount Vernon, Virginia. In 1799, the year of his death, Washington’s mash house produced 11,000 gallons of rye and corn whiskey (see sidebar, below).

Beer and wine provided the basis for ’alf and ’alf, a 50/50 mix of dark and light ale; shandygaff (beer plus non-alcoholic ginger beer); and sangaree, usually made of port, sherry, or other wine mixed with sugar and nutmeg. A version made with porter was called porteree. Sangaree is probably related to the Spanish sangria, a mix of fruit and red wine.

As 1800 neared, the communal punch bowl gave way to drinks mixed individually—the earliest versions of the modern cocktail, though not so labeled. Cocktail at first referred to a specific recipe, like a version mentioned in the May 13, 1806, Hudson, New York, Balance and Columbian Repository. Answering a reader query, the editor writes, “Cock tail [sic] … is a stimulating liquor, composed of spirits of any kind, sugar, water, and bitters,” a potent tool for politicians “because a person, having swallowed a glass of it, is ready to swallow anything else.”

Gradually Americans came to understand the term cocktail to mean any alcoholic concoction individually mixed and served by the glass. The etymology is vague. In a 1945 supplement to his book, The American Language, whiskey-loving journalist H. L. Mencken proposes several origin stories.

One popular theory has the word originating in New Orleans around 1800. Antoine Peychaud, a Haitian-born New Orleans apothecary who

in 1830 invented a brand of bitters—an alcoholic infusion of roots and herbs that bears his name and is integral to the Sazerac cocktail—sometimes gets credit. Legend holds that Peychaud served “medicinal” doses of spirits in egg cups—in French, coquetiers, perhaps corrupted into “cocktails.” However, use of cocktail preceded his apothecary shop. An alternate explanation has French roots—in coquetel, a mixed drink popular in 18th-century Bordeaux that French officers introduced to Americans during the Revolution

Use of “cock” to refer to the spigot on a whiskey barrel figures in yet one more origin story: Draining nearly empty barrels, barmen combined the dregs, selling the admixture cheaply as cock-tailings. Or perhaps the term came from cock-ale, a jolt of bitters and spirits supposedly fed fighting cocks about to enter the ring, or the way a swallow made an imbiber perk up like a horse cocking its tail. Spirits historian David Wondrich in Saveur in 2016 traced the name to a pre-race ginger suppository administered to racehorses.

Wherever “cocktail” came from, by the 1800s Americans had the mixed-drink habit. In his 1848 Dictionary of Americanisms, philologist John Russell Bartlett lists 59 drinks like mint julep, sherry cobbler, and milk punch, collected by studying menus from fashionable bars.

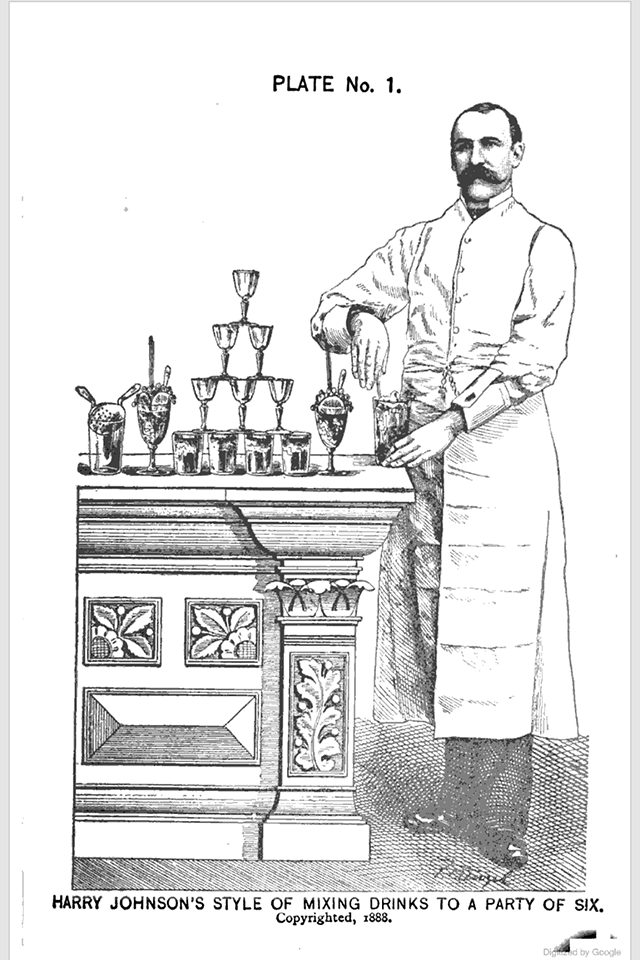

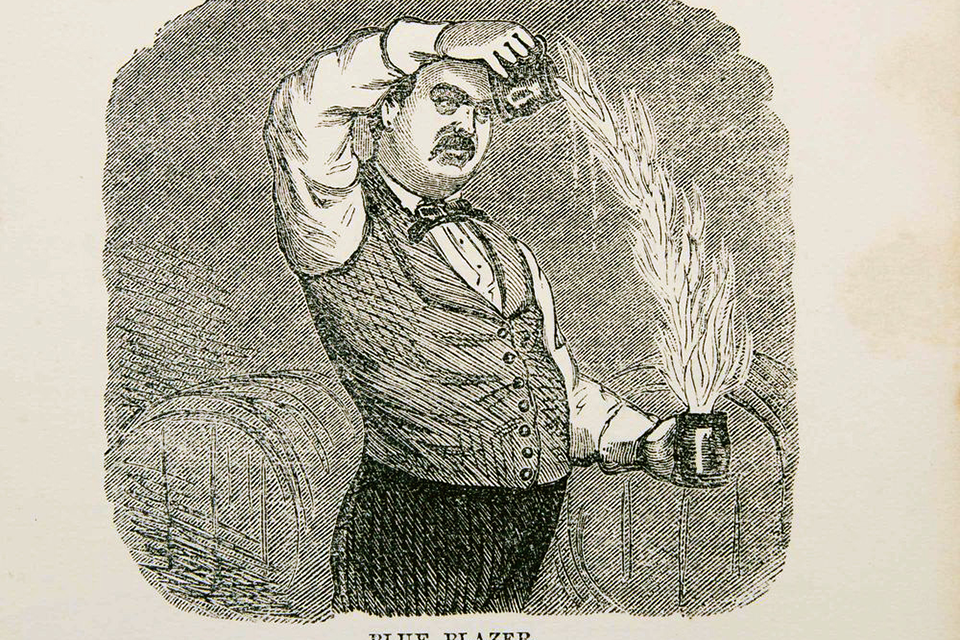

An 1862 booklet, How to Mix Drinks, or the Bon-vivant’s Companion, by Jerry Thomas, offers 236 recipes—a few, like lemonade, intended for teetotalers. Many recipes are variations on themes. According to both Bartlett and Thomas, the cocktail at that time was still a specific mixture. A given recipe used brandy, champagne, gin, or whiskey, plus a little water, a large shot of bitters, sugar syrup, and possibly other flavorings. Several recipes added a dash of Curaçao, a liqueur made from oranges. The “Japanese cocktail” contained orgeat

syrup (made from barley or almonds and orange flower water). The “Jersey cocktail” substituted cider for water. Thomas notes that many drinkers considered cocktails “good in the morning as a tonic.”

Another popular kick-starter, especially in the South, was the julep—a tall iced glass of bourbon, gin, or brandy with mint leaves, sugar, and sometimes fruit, crushed or muddled. Bartlett lists 11 juleps, ranging from plain mint to pineapple and strawberry. Virginians claimed to have invented the julep, whose name came from the Arabic for “rosewater.” Encountering the julep while traveling America in the 1830s, English writer Frederick Marryat declared that “with the thermometer at 100°” the julep was “one of the most delightful and insinuating potations that ever was invented.” A julep in a smaller glass was a smash.

The cobbler combined sugar, lemon, and ice garnished by orange slices and berries with wine, usually sherry, served in a tall glass with a straw. Some mix-masters went with sauterne, red Bordeaux, brandy, or Champagne. Similar ingredients went into slings, served hot or cold and made, according to Thomas, using brandy, whiskey, or gin.

The flip was a mix of beer, sugar, and nutmeg, sometimes enhanced by beaten egg whites. Thomas says a barman prepared this drink by whipping egg whites to a froth in one pitcher and stirring the other ingredients in a second, then pouring the contents back and forth until thoroughly blended and plunging a red-hot poker into the mixture to heat it. The beaten egg whites’ fleecy appearance led some to call flips “a yard of flannel.” A simpler sipper, combining brandy or whiskey, sugar, and boiling water and often drunk after dinner, was the hot toddy, whose name is part of a University of Mississippi football cheer.

Skilled bartenders, such as those whose drinks are listed in Bartlett’s dictionary, invented one-of-a-kind specialty cocktails. A “Moral Suasion” poured peach brandy, cognac, and flavorings over cracked ice. The “Knickerbocker” started with lemon or lime juice, adding rum, raspberry syrup, and a dash of Curaçao—the last also incorporated into the “Pousse Café,” a multilayered cocktail in which carefully poured

liqueurs’ differing densities create two to seven varicolored layers. The “White Lion,” akin to a Knickerbocker, also uses Curaçao, plus sugar. The “Dead Beat”—ginger soda and whiskey—was “taken by hard drinkers after a night’s carousal,” according to Bartlett. Other items he lists, such as bust head and bug juice—referring to cheap whiskey—and tangle leg, snap neck, and stagger juice—slang for dangerously potent alcohol—indicate that taverns were ready to serve straightforward shots of the hard stuff for those who just wanted a buzz. The ingredients for some of Bartlett’s most enticingly named cocktails—“Fiscal Agent,” “Virginia Fancy,” “Vox Populi,” and “Tippee na pecco”—are lost to history.

As cocktails were gaining in popularity in America, so was an anti-drinking movement spurred on partly by the Second Great Awakening of the mid-1800s. Methodists, Baptists, and others in the temperance movement, motivated by desire to protect families from alcoholic members, condemned “demon rum” and took the teetotal pledge to abstain from fermented drink.

By the late 19th century, the movement’s endorsement of prohibition had become a national cause with strong political clout. That power brought about the 1919 ratification of the 18th Amendment, under which the United States outlawed production, transport, and sale of alcohol. Prohibition lasted until 1933, making bootleggers rich, causing speakeasies to multiply, and landing many recipes for pre-1920 cocktails in history’s dustbin.

_____

Whiskey by Washington

Thomas Jefferson and other revolutionary leaders distilled liquor, but George Washington was the only founding father to run a commercial distillery. In 1797 James Anderson, who managed Washington’s estate, Mount Vernon, persuaded his employer to start turning his own and

his neighbors’ excess corn and rye harvests into alcohol. Operations started in 1798 at a site several miles from the main house. In 1799 Washington earned nearly $7,500 from whiskey sales, making his distillery one of Mount Vernon’s most profitable enterprises. When Washington died later that year, production halted. The distillery burned in 1814 and fell into ruin for more than 200 years, but in 2007 a carefully curated reconstruction opened for business. Visitors can tour the distillery, watch whiskey being made 18th-century style, and buy a bottle. mountvernon.org/distillery