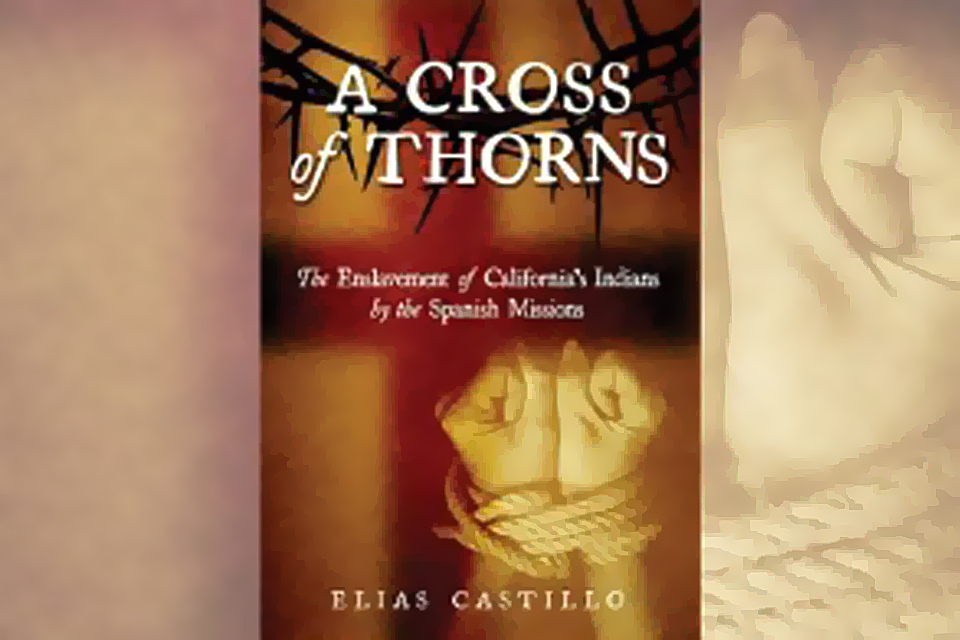

A Cross of Thorns: The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions, by Elias Castillo, Craven Street Books, Fresno, Calif., 2015, $19.95

In the National Statuary Hall Collection at the U.S. Capitol, California is represented by two prominent figures: President Ronald Reagan and Father Junípero Serra. The latter is honored for setting the standard for the 21 Spanish missions that helped establish civilization in the future state, in which Franciscan friars and the Indian “neophytes” they converted tilled the land in pastoral harmony. Or so, for centuries, we have been told.

Serra’s place in the Capitol comes under some dispute in A Cross of Thorns, in which journalist and three-time Pulitzer Prize nominee Elias Abundis Castillo unearths evidence in Serra’s own time describing the nightmarish realities of the missions. Even in the eyes of visitors from other colonial powers, such as Russia, France and Britain, the missions were, in practice, feudal fiefdoms on which the Chumash and countless other tribes served as virtual slaves. Pope Francis—or St. Francis of Assisi, for that matter—would have difficulty finding the principles by which they lived in the attitudes of the Spanish Franciscans, who regarded the Indians as subhuman, their lives in this world being of no concern against the cleansing of their souls in preparation for the next. After four Indians tried to flee Mission Carmel, Friar Serra sent a letter on July 31, 1775, to military commander Fernando de Rivera y Moncada, requesting he arrange to have his recaptured “lost sheep” flogged two or three times, adding, “If your Lordship does not have shackles, with your permission they may be sent from here.”

Political authorities frequently challenged mission practices, but the Franciscans had the Roman Catholic Church and the power of excommunication behind them, as well as control of vast tracts of arable land and the foodstuffs it produced. From their establishment in 1769 they used a combination of torture and conversion to eradicate all vestiges of Indian tradition, language and culture. That state of affairs finally changed in 1821 when the newly independent Mexican Republic brought the mission system to an end. As the author points out in his epilogue, however, the damage to California’s Indian heritage had been done. The Indians, newly freed but devoid of education or skills, continued to be degraded and victimized by the Mexicans and, from 1848 onward, by Americans, whose sympathy for their plight, if any, took a perpetual back seat to the discovery of gold. The author favors restoration of the surviving missions for their historic value, but he believes their preservation should include more accurate descriptions of their role as “death camps.”

—Jon Guttman

Originally published in the August 2015 issue of Wild West.