The Northwest Territory states were home to thousands of African Americans in the early 1800s

Anna-Lisa Cox is a non-resident fellow at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African and African American Research. Her work has underpinned two exhibits at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Cox’s latest book, The Bone and Sinew of the Land: America’s Black Pioneers and the Struggle for Equality (Public Affairs, $28), chronicles how free African Americans helped settle the Northwest Territory in the early 1800s. She says mainstream historians cling to a myth that whites settled the Midwest when long before emancipation the frontier Northwest Territory states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin were home to tens of thousands of free African Americans flourishing on their own land.

Who were these pioneers? Most came as free people, some from families that had been free since the 1600s. A relative few came on the Underground Railroad. By 1860, well over 300 settlements, from southeastern Ohio to Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, were home to African American farmers working land they owned. Evidence is growing that there is no place in the Northwest Territory states in which free people of African descent were not trying to live and work before the Civil War.

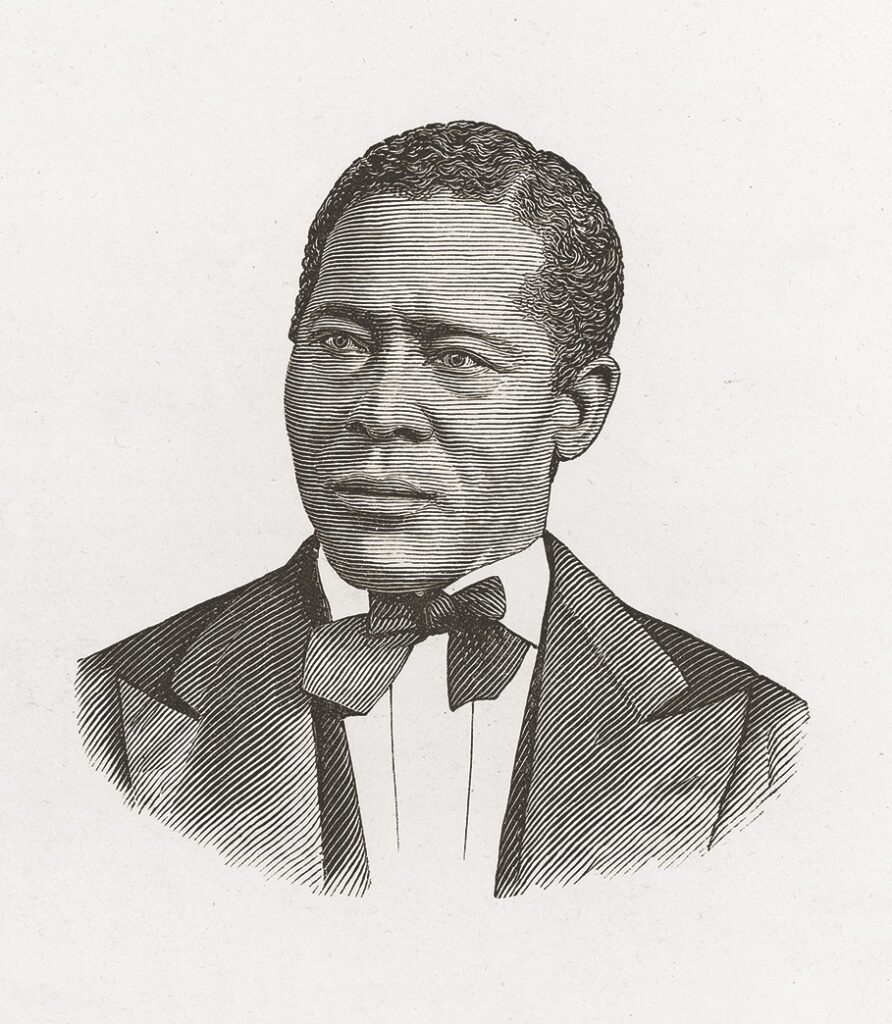

Some were “freedom entrepreneurs.” These were formerly enslaved people who had worked to earn money to purchase their freedom, often paying dearly—in some cases $1,000, at a time when $900 could buy a farm in Massachusetts. They are truly some of America’s superheroes. Imagine negotiating a price for yourself with someone the law says owns you—and, not infrequently, who is your kin—a white father, half-brother, or cousin! In Bone and Sinew, I tell the story of many of these freedom entrepreneurs, including Major James Wilkerson, whose family in Virginia sold him “down the river” to New Orleans. He still managed to purchase his and his mother’s freedom, moved to Cincinnati, and then led a black militia that defended their neighborhood against armed attacks by whites in 1841.

The 1787 Northwest Territory Ordinance banned slavery and promised equal voting rights there for any land-owning male citizen, regardless of skin color. Did those principles prevail? They did—for a while. Free African Americans were among the founding citizens of this territory, won from the British in the Revolution. Starting in the late 1700s, they could and did purchase frontier land and vote. The Ordinance, which reflected some of the Revolution’s most enlightened values, was written during a period that saw the rise of America’s first equal rights movement. In 1776 all 13 original colonies had enslaved people and were involved in the slave trade, but by 1804 eight of those 13 had created paths to ending slavery. By 1792 there were 15 states, and ten of those, including Kentucky, had removed the word “white” from their constitutions, opening the vote to all men regardless of skin color. Tennessee did so in 1796. Sadly, the backlash against liberty and equality started early in states of the Northwest Territory. By 1803 Ohio had inserted “white” into that new state’s constitution, banning African Americans from voting and reversing the intent of the 1787 Northwest Territorial Ordinance. Subsequently, whites in every state carved out of that territory stole the right to vote from fellow pioneers who were black, some of whom had defended those states during the War of 1812.

Most northern whites did not want to live with free African Americans. Racism in the antebellum Midwest arose in the face of black success. We think of lynchings and the like as a post-Civil War southern phenomenon—but by the 1830s many whites in the Midwest and the North were going to war against successful and propertied African Americans and their white allies, trying to negate by violence the ideals of the Declaration of Independence, most notably “that all men are created equal.”

What were “Black Laws”? Midwestern states enacted these laws to separate African Americans from the rights outlined in the 1787 Ordinance and to thwart further black settlement. There were many versions. African American children could not attend public schools in Ohio even though black property owners helped fund them through taxes. Some of America’s earliest anti-immigration laws targeted free people of African descent in the Midwest. In 1853 whites in Illinois authorized lawmen there to sell a free African American entering that state into slavery.

Still, African Americans persisted. There are many stories of hope and success. White and black neighbors risked their lives to help each other. African American parents became pioneers so their children could have a better life. In the 1810s Charles and Keziah Grier started with nothing on the Indiana frontier and ended up with a large, successful farm. They risked everything to become Underground Railroad operatives, most notably in the early 1850s when they helped facilitate the escape of members of William Still’s family. (Editor’s note: the recent film Harriet features a character based on William Still, an African-American abolitionist who worked closely with Harriet Tubman.) Charles Moore of Mercer County, Ohio, purchased his freedom and that of all of his family, and by 1840 had founded a thriving Ohio town that he named Carthagena after the African city of Carthage.

What was the Union Literary Institute? Wealthy black farmers and like-minded whites founded that pre-collegiate boarding school in rural eastern Indiana in 1845 to welcome students regardless of color, gender, creed, or social status. This was one of the only establishments of its kind founded and run by a board integrated by race and gender. The Institute encouraged equality on all levels, including cross-racial dating, and by the 1850s was known nationwide. Frederick Douglass covered it in his newspaper.

What were black conventions? This movement arose in the 1830s to fight racial violence and prejudice sweeping the nation, especially in the North. African Americans across Northwest Territory states demanded to regain rights stolen from them. Regional newspaper printed the texts of speeches by African-American equal-rights advocates. At an 1844 Ohio convention, an unidentified speaker said, “The Declaration of Independence, the American Bill of Rights, the Ordinance of 1787, as well as the political Creed of every intelligent, generous and patriotic freeman, are clearly violated, nay shamefully desecrated, by that feature of our constitution that renders the color of the skin a qualification for electors and suffrages. We shall urge our second plea upon the ground of justice. . .. ‘[D]o to others as you would have them do to you.’”

What strikes you most about these American pioneers? They showed incredible courage and perseverance. Despite terrible resistance, they continued to care for and grow their families and their farms while fighting for the best ideals of the United States—liberty, equality, and justice for all. If we continue to refuse to learn about this history, we lose some of the most tragic and hopeful aspects of our past—a past that continues to shape our nation today, whether we know it or not.