The air campaign at St. Mihiel, France, in September 1918 was among the most important events in the history of U.S. military aviation. “It was then-Col. William ‘Billy’ Mitchell’s show,” wrote historian John W. Huston. “He put together the largest air force ever committed to battle and drew up the plan for its employment.” Remarkably, considering the reputation he acquired after World War I for criticizing fellow military leaders, Mitchell successfully cobbled together the bulk of those air assets from three other Allied nations.

Only about 600 of the nearly 1,500 aircraft that participated in the Battle of St. Mihiel were flown by Americans in U.S. units. What’s more, fewer than 50 of those 600 airplanes were American-made, the others—mostly reconnaissance Salmsons, Breguet bombers and pursuit Spads—having been obtained from France. The remaining 900 machines were flown by French, British and Italian pilots. Interestingly, the Royal Air Force component—Airco and Handley Page single- and multi-engine bombers—was never actually under direct U.S. control, but because of the smooth cooperation between Mitchell’s staff and the British, that never became a problem. While American air strength would increase steadily between the St. Mihiel campaign and the Armistice two months later, never again during WWI would so much air power be amassed for any single battle.

Billy Mitchell was born into privilege in 1879, the scion of a prominent and wealthy Wisconsin family. His grandfather Alexander was a banker, railroad financier and U.S. Congressman. His father John was a U.S. Senator who had served as a first lieutenant in the Civil War.

In 1898 Mitchell entered the U.S. Army as a private, and for the next 18 years served in the infantry and Signal Corps. He was a latecomer to the flying game, receiving his pilot’s license in 1916, when he was 35 years old. By that time he’d already made a name for himself with the Army General Staff in Washington, D.C. His gifts as a soldier combined with his patrician background, superb horsemanship and natural social skills opened many doors for him. As late as 1913, he was still committed to the infantry and his beloved Signal Corps, believing that the airplane was only useful as a reconnaissance tool.

Mitchell openly fought efforts to keep the fledgling Aeronautical Division from splitting away from the Signal Corps. In this he was joined by a number of other future air leaders, including 1st Lt. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold. By 1916, however, Mitchell had completely reversed himself, becoming a zealous advocate of offensive air power under a separate Air Service.

Four days after the U.S. entered the war on April 6, 1917, then-Major Mitchell fortuitously found himself in Paris with a handful of other American military observers. On April 22, Mitchell wangled a trip to the front. That evening he wrote in his diary: “This has been one of the most important days of my life….I have seen the manner this war is made without the actual experience….I have been up in the front line trench during an attack.” Flying as an observer with a French pilot on the 24th, Mitchell became the first U.S. Army officer to fly over German lines. During the next few months, his knowledge of French and the ease with which he moved in Parisian social and political circles paved the way for him to become a prominent Allied air power advocate. He soon convinced American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) commander General John J. Pershing that he knew what he was talking about. In May he was promoted to lieutenant colonel, in October to full colonel.

Mitchell’s organizational and aerial war-making abilities fully matured during the agonizingly long buildup and training of American forces from mid-1917 to mid-1918. After a careful review of the static trench warfare and resultant human slaughter of the previous three years, Mitchell concluded that a new offensive approach was imperative if the Allies were ever to break the stalemate. He noted the rapid technological advances that Britain and France had made since 1914 in both single-seat fighters and heavy bombers. When war first broke out, airplanes had a top speed of 65 mph and a maximum range of 200 miles. Three years later, pursuit ships were approaching 120 mph and the new multi-engine bombers could cruise at 85 mph with a 650-mile range. Just around the corner were such advanced long-range British bombers as the twin-engine Vickers Vimy and the four-engine Handley Page V/1500, both of which were expected to be available by early winter 1918. Mitchell realized that with such machines even Berlin could be bombed from aerodromes in England. He became convinced that airplanes in great numbers were key to the Allied ground armies finally overwhelming Germany’s Western Front defenses.

The year leading up to September 1918 was a time of great uncertainty regarding the character and mission of what would become the U.S. Army Air Service (USAS). Pershing and Mitchell wanted to bring the fight directly to the enemy and advocated for a strategic air force of both fighters and bombers, while war leaders in Washington, thoroughly behind the times and with veto power over Pershing, insisted on concentrating aircraft production on light reconnaissance machines. Both approaches suffered from the lack of adequate ocean shipping to get any kind of airplanes to France.

Despite Mitchell’s best efforts and to his bitter disappointment, Woodrow Wilson’s administration placed its highest priority on reconnaissance planes. As Alfred F. Hurley observed in his book Billy Mitchell, “This decision started the production program in the wrong direction at a time when every moment was too precious to be wasted.” Mitchell himself opined in his memoirs that it “constituted one of the most serious blunders that has ever occurred in our military service.”

Recommended for you

Mitchell worked tirelessly with French officials and key AEF officers to make do with whatever equipment was provided to the U.S. flying service. In July 1918, Pershing, very much pleased with Mitchell’s efforts, named him chief of the Air Service, First Army—the top combat position. Mitchell promptly served notice that he intended to build an air fighting force so powerful he could “blow up Germany.” His mantra: massive concentrations of aircraft, strategic penetrations behind enemy lines to interdict men and equipment moving to the front, and forcing German fighters to engage with the much stronger Allied air forces. Any residual concerns before the battle about his commitment to the overall AEF objectives were swept away when he firmly declared that “the Air Service of an Army is only one of its offensive arms. [Its role is to help] the other arms in their appointed mission.”

Early on, Mitchell had become well known for his aggressive and often dangerous reconnaissance flights. While he was no more than an average pilot himself, even his Air Service enemies praised his courage and tactical skills. American pilot training had been another matter: Although there were plenty of volunteers, there just wasn’t enough time to bring them up to true wartime standards. In April 1918, and probably against his better judgment (the French and British were screaming for Pershing to get his men into action), Mitchell felt compelled to declare the first American aero squadron sufficiently trained for combat. European air servicemen openly demurred, rightfully believing the Yanks were woefully inexperienced. Privately, Mitchell probably agreed, but there was really no choice—the war had reached its most crucial stage, and it was now or never for the Americans.

Mitchell believed his men’s courage and élan would be the great equalizer. Furthermore, he knew his non-regulation uniforms and bon vivant lifestyle delighted the rank and file. Despite the appalling loss of life over the spring and summer in accidents and combat, his fliers never wavered in their willingness to follow him down the barrel of a cannon. And while Mitchell’s apparent laxity off-duty may have suggested sloth to outsiders, he was ruthless about maintaining strict ground and air discipline. He refused to ease up on his pilots, even after the death of his brother John in a flying accident. (“This is war,” Mitchell consoled his mother. “It has to be kept up until one or the other breaks.”) While the USAS quickly matured and the American airmen fought bravely, it would never field more than 650 planes in action (during the later fight at the Meuse-Argonne, the AEF’s only other major battle).

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

In late summer 1918, Marshal Ferdinand Foch, supreme Allied commander, ordered Pershing to break the four-year stalemate along the St. Mihiel sector of the Western Front. Foch dispatched 110,000 French troops to support Pershing’s 550,000-man army in the ground assault. Mitchell was put in command of all Allied air forces in this combined air/ground assault. His job was to coordinate and blend air assets that eventually totaled 1,481 multi- and single-engine bomber and pursuit planes flown by American, British, French and Italian airmen. The orders went out to all air commanders: Attain air superiority and provide aggressive ground support along the entire battle line.

The three-day offensive at St. Mihiel, the initial stage of what would be the final assault against Imperial Germany, began on September 12. Over the next three days, wave after wave of Allied planes, in close cooperation with ground forces, never let up their unrelenting pressure on the German war machine. In retrospect, considering the remarkable success Hermann Göring and his Luftwaffe would have in combined air/ground “lightning war” a generation later, it’s tempting to conclude the Germans learned more from Mitchell’s stunning air offensive than did the Allies.

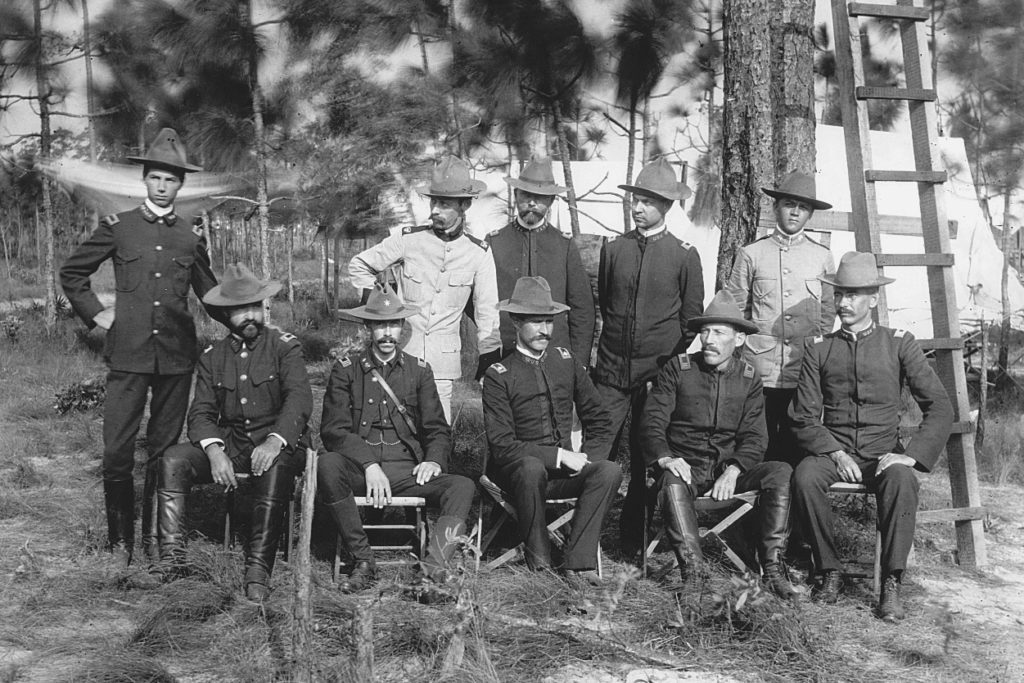

Colonel Mitchell and his loosely organized staff of senior Allied airmen directed the battle in hands-on fashion. Mitchell took his cues from Pershing, acting in strict subordination to AEF needs in the ground fighting. The combined air forces—600 American-piloted machines, 500 French fighters and bombers, the RAF’s Independent Force of bombers and a handful of Italian Caproni trimotor bombers—operated within less than a 35-mile radius from the center of the assault. Although Germany’s rather meager force of 243 aircraft included the highly experienced Fokker D.VII pilots of Jagdgeschwader II and Jagdstaffel 18, Mitchell’s air offensive ultimately overwhelmed them, delighting Pershing. With absolute control of the air, Pershing’s ground armies were able to smash through the St. Mihiel salient. Just days after the battle, Mitchell was promoted to brigadier general.

There was no stopping the Allied juggernaut. The Germans moved Jagdgeschwader I, the late Manfred von Richthofen’s famed “Flying Circus” fighter wing, into the sector and mounted another desperate defensive stand in the Meuse-Argonne, which set up the climactic battle on the Western Front. On October 15, Mitchell was given command of the entire USAS in France. He kept the pressure on, sending hundreds of Allied bombers behind the lines to strike strategic targets. During this short period, Mitchell’s men dropped half of all AEF bomb tonnage released during the entire war.

Regrettably, by the time the November 11 Armistice abruptly brought hostilities to an end, Mitchell’s ground commander peers had become jealous of his tremendous success. Fearful the glamorous airmen would claim too much credit for the victory, AEF officials produced after-action reports that seriously downplayed the important contribution the air services had made in the breakouts at St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne. As a result, Mitchell’s air campaign was never properly appreciated during the postwar period.

Mitchell was dismayed that other U.S military leaders did not share his vision of the vital role the airplane would play in future wars. This led him, unfortunately, to overplay his hand. During the early 1920s, his overreach in demanding an Air Service independent of the Army and his ceaseless bickering with Army and Navy leaders contributed to bitter interservice rivalries and the resultant decline in American military preparedness.

Despite Mitchell’s famous 1921 sinking by air of the captured German battleship Ostfriesland, which vividly demonstrated how vulnerable the Navy’s surface vessels were to aerial bombardment, little was done between the wars to bolster America’s air assetts. Mitchell’s willful contentiousness ultimately led to his court-martial in October 1925. He was charged with violating the 96th Article of War, a catchall provision of military law that allowed an officer to be charged for any action “of a nature to bring discredit upon the military service.” Found guilty, he was suspended from duty and ordered to forfeit all pay and allowances for five years. Mitchell responded by tendering his resignation and retiring from the Army.

Mitchell’s warnings about the vulnerability of Pearl Harbor would soon be forgotten, most pointedly his prediction that Japan would attack Hawaii on a Sunday morning! The buildup of an American strategic bomber force—something he lobbied for the rest of his life (he died in 1936 at age 56)—finally gained traction after the Japanese and German threats became too much to ignore in the late 1930s. By the time war broke out in 1939, the stalwarts of the future Eighth Air Force in Europe—the B-17 Flying Fortress and B-24 Liberator—were barely in production or still on the drawing board.

Mitchell’s genius was recognized only after it became clear how prophetic he had been. In 1942, in an acknowledgment of his contributions to air power, President Franklin Roosevelt posthumously promoted him to major general on the Army Air Forces’ retired list. In 1946 he was awarded a special Congressional Medal of Honor “for outstanding pioneer service and foresight in the field of American military aviation.” He is the only individual to have a U.S. military aircraft named after him, the B-25 Mitchell medium bomber.

Robert O. Harder served as a U.S. Air Force B-52 navigator-bombardier and civilian flight instructor. He suggests for further reading: Billy Mitchell: Crusader for Air Power, by Alfred F. Hurley; Hostile Skies, by James J. Hudson; and The U.S. Air Service in World War 1: Vol. III, by the Air Force Research Historical Center.