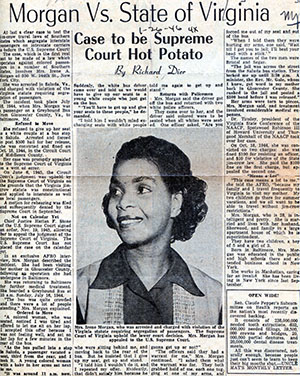

Irene Morgan’s landmark civil rights stand went to Supreme Court in 1946

ON JUNE 3, 1946, the U.S. Supreme Court, for the first time in its history, ordered racial desegregation. The ruling came in a dispute that had begun nearly two years earlier, on July 16, 1944. That Tuesday, Irene Morgan, a feisty 28-year-old African-American mother of two, boarded a Greyhound bus at the Hayes Store crossroads stop in Gloucester County, in Virginia’s Tidewater region. Morgan was heading home to her family in Baltimore after visiting her mother in the country. She took a seat three rows from the back of the bus beside another African-American woman who was carrying an infant. Stop by stop, seats filled. By Saluda, Virginia, 20 miles north, several passengers were standing, though the back bench seat was not full. At Saluda, two white passengers boarded. The bus driver, R.P. Kelly, asked Morgan and seatmate Estelle Fields and her baby to move to the back of the bus. Despite Morgan’s urging that she keep her seat, Fields relocated with her child to the bench.

However, Kelly had picked one wrong target. Still recovering from a recent miscarriage, Irene Morgan was not in a cheery mood and in any case was not a woman to tolerate nonsense or insult. She had grown accustomed to industrial urban life with its greater racial integration and to the independence she had achieved working in a Baltimore plant turning out Martin B-26 Marauder medium bombers. Morgan forcefully refused to move.

“I wasn’t going to take it,” she said later. “I’d paid my money.”

Virginia law forbade blacks and whites to sit next to one another on buses. Vehicles did not designate “black” or “white” seats although

segregationist states historically had expected African-Americans to relegate themselves to the back of the bus. As passengers came and went, a bus driver was supposed to rearrange his customers along racially separate lines. If Kelly could not persuade Morgan to move, he himself would be guilty of a misdemeanor.

When Morgan balked, Kelly steered his Greyhound straight to the Saluda sheriff’s office. A Middlesex County deputy boarded to arrest the recalcitrant traveler. Morgan wasn’t having any. The sheriff “didn’t even know my name,” she told a Washington Post reporter, so she doubted the legitimacy of the warrant he was waving. “I just took it and tore it up and just threw it out the window.” That led to a scuffle during which Morgan kicked the lawman in the groin. “I started to bite him but he looked dirty, so I couldn’t bite him,” she said. “I clawed him instead. I ripped his shirt.”

The sheriff and a deputy dragged Morgan from the bus, charging her with resisting arrest and violating Virginia law calling for racial segregation on public transportation. She spent eight hours in the county jail before her mother showed up with $100 cash to cover her bail. At trial three months later, in October 1944, Irene Morgan admitted to resisting arrest and agreed to pay a $100 fine.

But she would not plead to the segregation violation. Convicted, she was ordered to pay a $10 fine. She refused to pay. Civil rights lawyers working to unravel the web of law and custom that demoted African-American citizens to second-class status saw in Morgan’s $10 fine the perfect occasion for a legal challenge. A cadre of men later to be their generation’s most eminent African-American jurists signed on to defend Morgan, prepping her dispute for a journey to the U.S. Supreme Court. The lady who wouldn’t move to the back of the bus was, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People secretary Walter White noted in a letter soliciting contributions to fund Morgan’s litigation, one of the “obscure men and women who are the plaintiffs in cases which result in decisive gains in the practical enjoyment of our constitutional freedom by all our citizens.”

Eleven years later, Rosa Parks would become a civil rights heroine by refusing to move to the back of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Irene Morgan, as U.S. District Court Judge Louis H. Pollak observed later, at the very least might be termed “Rosa Parks’s mother-in-law.”

By 1944, much of America, even if racially segregated by habit and social norms, had begun to consider it wrong to have mandated segregation. Eighteen state legislatures had passed laws banning racial segregation on buses.

But laws in Virginia and nine other states demanded the practice. The rationale for those laws, Virginia’s lawyers would tell the Supreme Court, was that they were a realistic reaction to blacks’ and whites’ natural mutual enmity.

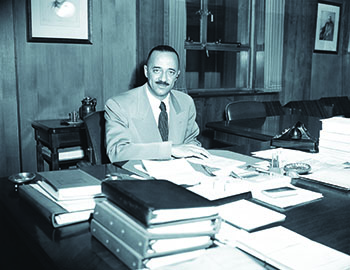

Morgan meant to fight. “If something happens to you which is wrong, the best thing to do is have it corrected the best way you can,” she said. She struck pay-dirt when she walked into a Richmond, Virginia, law office and asked its proprietor to take her case. Spottswood W. Robinson III, 28, was already making a name for himself in legal circles—not only graduating first in his class at Howard University law school but doing so with the highest total grade point average in the institution’s history. He immediately joined the Howard Law faculty, meanwhile with another lawyer opening a practice in Richmond, eager to use litigation to advance the causes of minorities.

Studies of that era’s African-American attitudes point to the daily indignity of segregated public transportation as the emblem of second-class status blacks resented most. Robinson had heard from many African-Americans who had defied segregated seating on buses; they wanted him to attack the charges against them as based on an unconstitutional practice. But segregationist states were wary of a showdown, so typically when arresting an African-American for refusing to comply with racist seating arrangements, authorities leveled a charge of disorderly conduct. That deprived lawyers like Robinson of a crowbar with which to undo the underlying race-based laws. But the Middlesex County authorities had not stopped with a disorderly conduct charge; they had tacked on a segregation violation. “When Irene Morgan told me that she had been charged with violation of the segregation ordinance, I couldn’t believe my ears,” Robinson said. “I looked at the charge sheet, and there it was—violation of that ordinance.” That provided the essential legal lever, and the NAACP agreed to back Morgan’s appeal of her conviction.

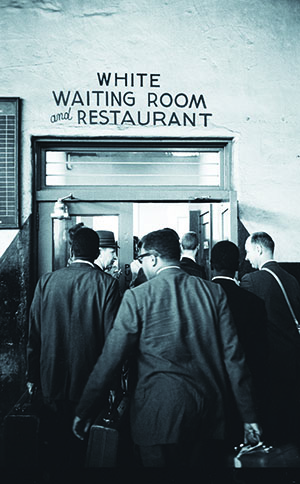

(Photo by Paul Schutzer/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

The 14th Amendment to the Constitution promises that no state may “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Civil rights advocates read that as meaning that segregation laws—by demanding separate accommodations for blacks and whites—were inherently unconstitutional. But activists knew that in 1946 this argument would not win in court. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court, reviewing a Louisiana law requiring that blacks and whites ride in different rail cars, had ruled 7-1 in Plessy v. Ferguson that mandating “separate but equal” facilities for people of different races did not deny anyone equal protection. Fifty years on, Plessy remained the prevailing legal doctrine.

The concept that state laws had to provide equal treatment to people of all races—even if that treatment was separate—had been employed in previous challenges to argue against practicing segregation in public transportation. As early as 1914, the high court held that the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, complying with an Oklahoma segregation law, acted improperly when the railroad refused to allow a black passenger to book a berth in a sleeping car. The court reaffirmed that reasoning in 1941 in a case that was brought by Rep. Arthur W. Mitchell.

The son of former slaves, Mitchell was the first African-American Democrat elected to the U.S. House of Representatives; he represented Chicago’s South Side from 1935 until 1943. In 1937, Mitchell, traveling on a first-class ticket from Chicago to Hot Springs, Arkansas, on the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad, was asked when the train crossed into Arkansas to move into a less cushy blacks-only coach; he argued that the practice was unlawful. Mitchell argued his own case before the court, which unanimously agreed that all holders of first-class tickets had the right to occupy first-class seats throughout their trips. The decision was “a step in the destruction of Mr. Jim Crow himself,” Mitchell exulted.

But neither the Oklahoma nor the Arkansas ruling forced American passenger railroads to integrate services. Lines could achieve compliance by dropping sleeping car or first-class coach service or offering those services in separate facilities to black and white passengers. State laws demanding that blacks and whites not sit together in buses involved accommodations that were more or less equal, so Robinson and the NAACP could not invoke those decisions as precedents in Morgan’s case. When the Supreme Court agreed to consider Morgan’s appeal of a Virginia appellate court ruling upholding her $10 fine, her lawyers fastened on a more promising strategy: ignoring how transportation segregation laws affected minority passengers and focusing on how those laws affected businesses that operated the carriers.

The Constitution authorizes Congress “to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states.” Supreme Court decisions had interpreted the commerce provision as making it unconstitutional for states to regulate interstate business operations if rules impose substantial hardship on those businesses. Ironically, that interpretation came in a case in which a state legislature had been pursuing exactly the opposite goal: The justices in 1878 struck down an 1869 Louisiana ban on racial segregation in all public transportation because of the passenger-shuffling burden imposed on operators of a Mississippi River steamship. Morgan’s lawyers would wield that pro-segregation ruling as a cudgel against segregation.

When the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to take Morgan’s case, Robinson had to line up allies; he was not qualified to argue cases in person before the top tribunal because he did not have enough experience. As lead attorneys in the case he recruited William H. Hastie and Thurgood Marshall, lions among the day’s African-American civil rights lawyers. In 1944, Hastie and Marshall had won a major victory when the justices, ruling 8-1, struck down a Texas law allowing the Democratic Party to hold whites-only primaries. Structuring their approach to Morgan’s case, Robinson, Marshall, and Hastie worked out a division of labor. Robinson primarily would be responsible for the written brief. Marshall would make the oral argument before the justices on March 27, 1946, and lay out exactly what happened to Irene Morgan that July day in 1944. Hastie then would present an argument for finding the Virginia segregation law unconstitutional.

Hastie’s demeanor made him the ideal closer, according to Robinson. “His courtly reserve was emblematic of an ability to approach the problem from a perspective divorced from the emotions of a lifetime—emotions deeply felt but kept completely under control,” the younger man said. And Hastie focused relentlessly on the possible, creating “prescriptions for social change” that the justices could find both morally and legally persuasive, Robinson added.

Morgan’s brief to the court noted that “we are just emerging from a war in which the people of the United States were joined in a death struggle against the apostles of racism,” and that in signing the United Nations charter, the United States had made it “our duty, along with our neighbors, to eschew racism in our national life.”

But Morgan’s lawyers knew high-flown prose would not accomplish their ends; the votes to strike down the separate-but-equal doctrine simply were not there. “Pushing the court too fast or too far would almost certainly lead to a setback for the cause of civil rights,” historian Raymond O. Arsenault wrote. To erase state mandates for segregated seating in interstate bus travel, Morgan’s team had to persuade the justices that Virginia’s law—and by extension measures in the nine states with similar statutes—so burdened interstate commerce as to be unconstitutional.

“The national business of interstate commerce is not to be disfigured by disruptive local practices bred of racial notions alien to our national ideals,” Morgan’s lawyers wrote. From the bench, Justice Wiley E. Rutledge tried to push Hastie to argue that segregated seating was an example of blacks being denied the equality the 14th Amendment guarantees, but Irene Morgan’s lawyer refused the bait. “Hastie resisted his strongly held views on Plessy, and instead took a course that was at once wise and bold,” Robinson said. “His response was that the litigation before the court neither required nor urged a reconsideration of Plessy, but he intimated that someday he would be back with just such a challenge.”

Hastie instead concentrated on the difficulties that varying state segregation laws imposed on transportation companies. To illustrate, he and his associates had hypothesized a cross-country bus journey to show how often a driver would have to reseat passengers as his vehicle passed from states demanding segregation to those with no such laws to those that outright forbade

segregation. The hypothetical trip went from Pennsylvania to Mississippi. Pennsylvania outlawed segregation; Maryland imposed it on intrastate travelers but not those bound from or to another state. The District of Columbia had no rules on racial seating, but when the journey continued into Virginia, resegregation again was mandated. Next came Kentucky, which, like Maryland, required segregation of intrastate passengers but had no statute covering interstate passengers. From Tennessee on to Mississippi, the local laws required segregation of all passengers. The brief for Morgan v. Virginia was “a marvel of advocacy,” Pollak wrote.

The brief was also effective. Voting 6-1, the court held that segregationist state laws like Virginia’s were unconstitutional. The path to that decision was bumpy: precedents did establish the unconstitutionality of state laws imposing an undue burden on interstate commerce, but in private talks the justices homed in on the true degree of burden imposed by segregated seating laws. In his private discussions with other justices, Chief Justice Harlan Stone argued that “interference with commerce was not very great” as a result of adherence to varied state laws on racial segregation. Countering that argument, Justice Stanley Reed insisted that the “constant arrangement of seating is disruptive.”

In the nine weeks between the Supreme Court hearing and issuance of its decision, Stone had died and Justice Robert H. Jackson had stepped down temporarily to serve as chief U.S. prosecutor at the trials of accused Nazi war criminals in Nuremberg, Germany. Justice Reed, tapped to develop the court’s formal opinion, wrote, “It seems clear to us that seating arrangements for the different races in interstate motor travel require a single, uniform rule to promote and protect national travel.” In other words, segregation was out and racially integrated travel was the law of the land. Carriers would not be able to dodge the ruling by offering “separate but equal” accommodations.

Rep. Adam Clayton Powell (D-New York), Harlem’s representative in Congress, lauded the decision as “the most important step towards winning the peace since the conclusion of the war.” Within a year, civil rights activists trying to put the ruling into practice were chanting, “Get on the bus, sit any place /’Cause Irene Morgan won her case.”

Morgan did not lead to immediate integration of interstate bus travel. Bus companies resisted the change, claiming they were continuing segregation as a matter of company policy—at the time, still legal—not because state law required it. But the ruling did have immediate judicial impact. Marshall, calling the decision “a decisive blow to the evil of segregation and all it stands for,” announced that the NAACP, where he held the title of special counsel, would use Morgan to push on with 98 pending challenges to racial segregation in interstate travel. The ruling led to a string of civil rights victories in which courts declared other forms of legislated segregation unconstitutional as undue burdens on interstate commerce. Just months after the high court ruling in Morgan, the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, DC, extended Morgan to apply to rail travel. In 1948, the Supreme Court cited Morgan in ordering integration of pleasure boats traveling between Michigan and Canada. And in 1950 the justices ruled that a bus terminal is so integral to interstate travel that Virginia could not use its segregation statute to deny an African-American passenger access to a “whites only” restaurant in the Richmond bus terminal.

The decision remains an important precedent, although 21st-century cases most commonly reference it in regard to business matters with no racial or civil rights overtones. In 2013, the U.S. Court of Appeals in Philadelphia cited Morgan in a dispute over sports gambling.

As pertinent as the case may be for today’s business lawyers, Morgan and its watershed civil rights role faded from public awareness as the civil rights movement brought courts ever more pervasive and contentious issues—school desegregation, voting rights, discrimination in employment and in housing—especially after the high court in 1954, finding separate to be inherently unequal, ordered public schools desegregated, reversing Plessy. One massive study of the NAACP’s battle against racism from 1909 through 1969 does not even mention Morgan.

Irene Morgan went on with her life. After her husband died, she remarried, moved to New York City, and ran a childcare center in Queens. At 68, she earned a bachelor’s degree from St. John’s University and five years later a master’s degree in urban studies from Queens College. When she was in her 80s, she left Staten Island for Gloucester County, Virginia, scene of her anti-segregation stand.

Morgan lived four months past her 90th birthday—long enough to enjoy the glow of the spotlight as it swung back to her and the victory arising from her simple refusal to move to the back of the bus. In her last years, she received official recognition for her indomitability of more than a half-century before. In 2000, when Gloucester County celebrated its 350th anniversary, she was one of its honored citizens. In 2002, the NAACP gave the 85-year-old its Freedom Fighter Award. Upon her death in 2007, The New York Times published a long obituary, noting that her “fight against segregation took place a decade before the modern civil rights movement changed America.” Posthumously, Maryland added Morgan to her home state’s Women’s Hall of Fame. And in 2012, Virginia authorities unveiled a plaque designating the Middlesex County Courthouse a historic site at which Morgan’s resistance “helped set the precedent for the later battles the NAACP waged against segregation.”

But arguably the most satisfying of Irene Morgan’s limelight moments had come in 2001, when President Bill Clinton awarded her—along with baseball’s Hank Aaron, boxing’s Muhammad Ali, and the federal judiciary’s Constance Baker Motley—the Presidential Citizens Medal. Morgan’s “courage and tenacity,” the White House citation proclaimed, “helped make America a more just society.”

This story was originally published in the December 2017 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.