In June 1864 two of the Civil War’s fiercest cavalry commanders faced off at Trevilian Station, Virginia.

As Union brigadier general George Armstrong Custer barked out orders, the troops of his Michigan Brigade perfected their defense, churning up the dust as they deployed. They had just captured a large number of Confederate wagons, caissons, horses, and prisoners. But they were behind enemy lines in Virginia. Southern cavalrymen had the 800 Michiganders surrounded, caught inside what one Union trooper called “a living triangle.”

As enemy troops swirled around them, many of Custer’s squadrons remained mounted—a requirement for quick counterthrusts—but some took to the ground. On the eastern edge of the encirclement, dismounted horsemen hurriedly knelt behind a fence-rail barricade, their Spencer repeating carbines glistening in the midmorning sun.

When the Confederates attacked, they suddenly seemed to be everywhere at once. According to Michigan trooper Harmon Smith, they were fighting “at the front, in the rear, at the right and at the left.” Shouting above the incessant firing, a muddled officer asked Custer whether they should move the captured Rebel property to the rear. “Yes, by all means,” the young general replied. “Where in hell is the rear?”

Fought on June 11 and 12, 1864, the Battle of Trevilian Station was a contest between two of the war’s most aggressive cavalry commanders: Union major general Philip Sheridan and Confederate major general Wade Hampton III. At stake was a major section of the Virginia Central Railroad, the main rail link between the Shenandoah Valley—known as the breadbasket of the Confederacy—and General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The largest all-cavalry battle of the Civil War, Trevilians is also important for several other reasons. It not only illustrates the evolution of Civil War horse soldiers into mounted infantrymen but also marks Hampton’s emergence as a successful commander of Lee’s cavalry. Perhaps most important, the Confederate victory, because it safeguarded a critical Southern rail line, considerably prolonged the Civil War.

The Battle of Trevilian Station was fought in the third year of the Civil War, in the second week of June 1864. Just 10 miles northeast of Richmond, the Union’s Army of the Potomac under Major General George Meade—with his superior, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, looking over his shoulder—was stalled after launching disastrous assaults against Lee’s earthworks at Cold Harbor. The direct route to the Confederate capital was blocked, so Grant determined to move his huge army across the James River and take Petersburg, some 20 miles to the south. To accomplish this grand movement, Meade’s forces would have to draw off the bulk of the Confederate cavalry. A major diversion was needed.

On June 5 Meade ordered Sheridan, his cavalry corps commander, to ride west and capture Charlottesville. “Destroy the railroad bridge over the Rivanna [River] near that town,” read the orders, “[and] thoroughly destroy the [Virginia Central] railroad from that point to Gordonsville.” In the Shenandoah Valley, Union major general David Hunter had just won the Battle of Piedmont and had captured the city of Staunton. On June 6 Grant instructed Hunter to cross the Blue Ridge Mountains and, moving east, thoroughly tear up the Virginia Central tracks until he joined forces with Sheridan. These two forces, once combined, could wreak further havoc on Confederate supply lines throughout Central Virginia.

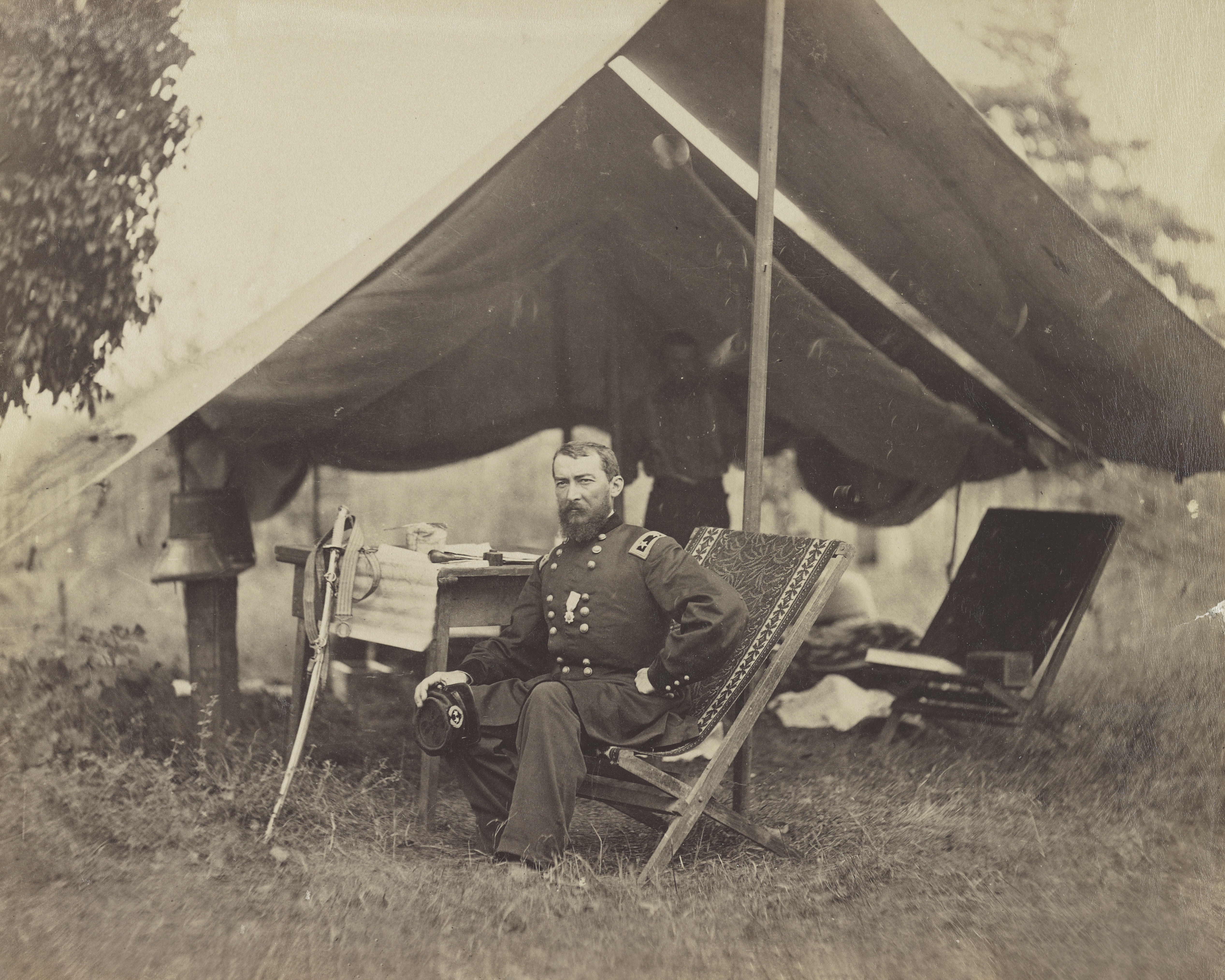

Born in Albany, New York, in 1831, Sheridan had graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1853. Starting off the war as a quartermaster, he was transferred to the cavalry and then the infantry, rising steadily in the ranks. Having distinguished himself on several battlefields, he came to Grant’s attention on November 25, 1863, when his infantry division—against orders—successfully stormed dug-in Confederates at Missionary Ridge, Tennessee. When Grant came east in early 1864, he brought along Sheridan to command the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry.

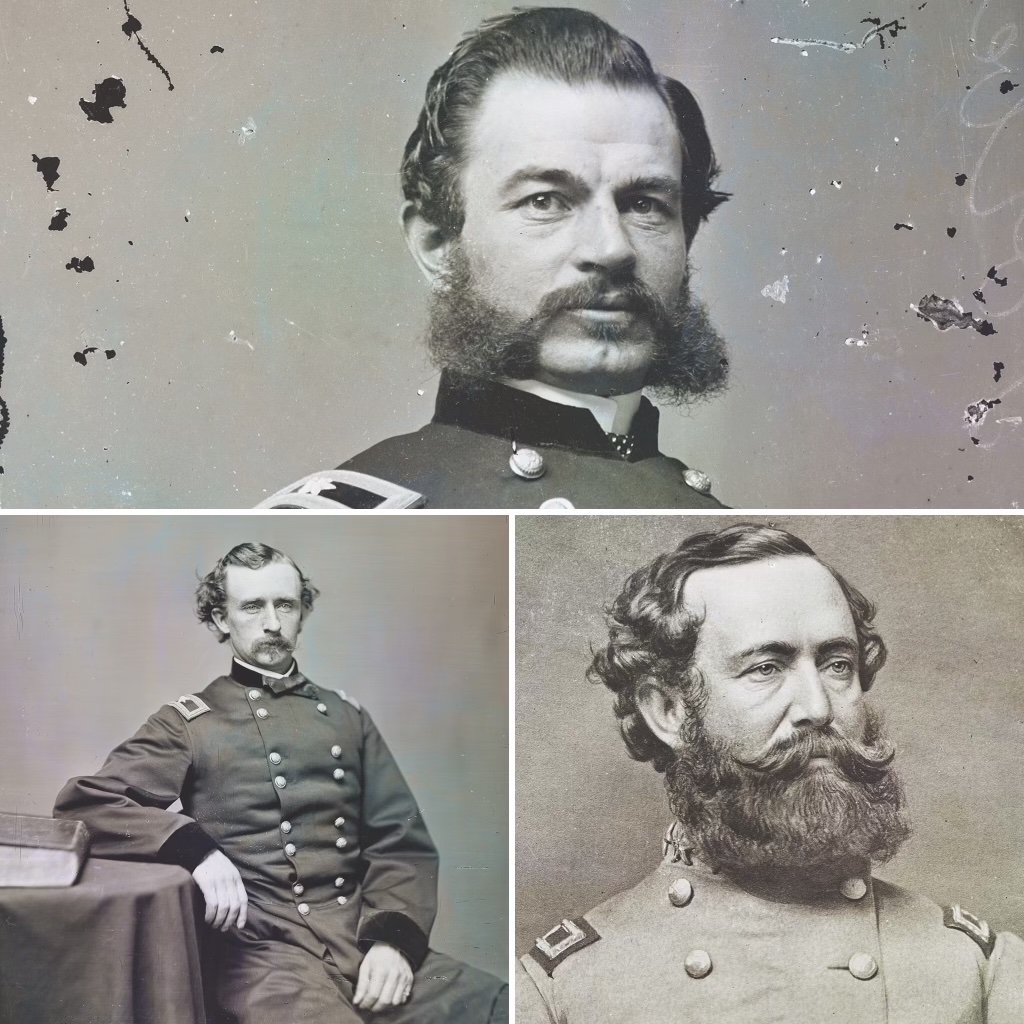

“Little Phil” Sheridan—“a small, broad-shouldered, squat man with black hair and a square head,” as a contemporary described him—set out confidently on June 7. As Sheridan would later write, he chose to march along the north bank of the North Anna River, cross the river at Carpenter’s Ford, and strike the Virginia Central Railroad at Trevilian Station, destroying rails there and between Gordonsville and Charlottesville to the west. Sheridan’s massive raiding party comprised two cavalry divisions under the command of Brigadier Generals Alfred T. A. Torbert and David M. Gregg, both 31-year-old West Point graduates. The 9,200-man force, jangling along with its 20 pieces of artillery and 125 wagons, took up nearly six miles of road.

On June 10 Sheridan’s horsemen splashed across the North Anna and went into camp a short distance beyond, near Clayton’s Store. Trevilian Station was just a few miles to the southwest. Once his experienced horsemen were astride the tracks the next morning, they would pry up the iron rails and bend them into uselessness after heating them atop blazing bonfires made from the ties. According to the plan, his next targets were Gordonsville and Charlottesville. What Sheridan hadn’t counted on, however, was the reception Hampton planned for him.

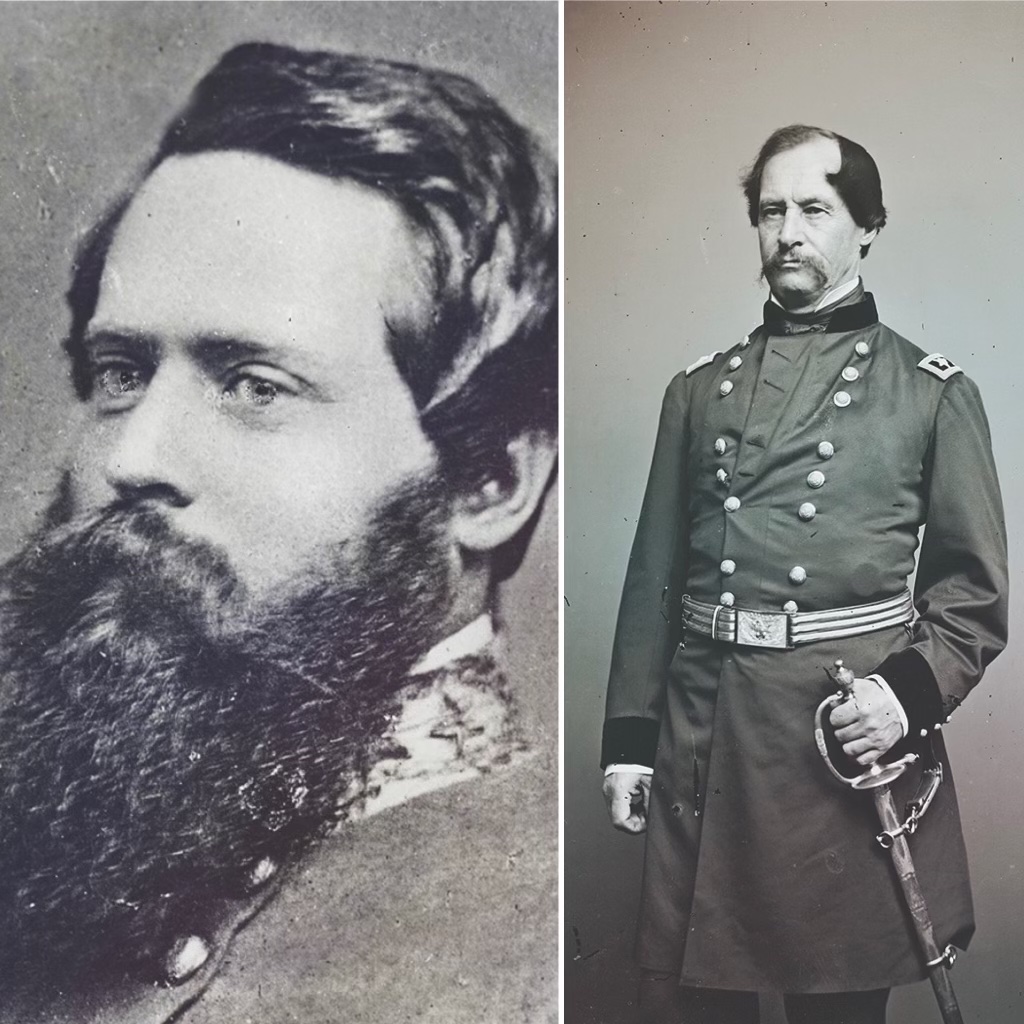

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1818, Hampton had been one of the South’s wealthiest plantation owners. When South Carolina seceded, he’d raised, uniformed, and equipped his own force—the Hampton Legion. “He looked a grand military chieftain,” wrote an admiring Southern cavalryman, “full-bearded, tall, erect, and massive; a horseman from life-long habit and natural aptitude.” By the spring of 1864 Hampton had become the senior major general—second in command—in Major General J. E. B. Stuart’s Cavalry Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. When Stuart was mortally wounded on May 11, however, Hampton—despite his seniority and a commendable battlefield record—was not immediately confirmed as chief of cavalry. Instead, Lee had the three cavalry division leaders report directly to him.

Hampton learned of Sheridan’s movement on June 8. With Lee’s permission, by daylight the next morning the 4,400 cavalrymen of Hampton’s 1st Division were on the move. This force consisted of three brigades: one under Colonel Gilbert J. Wright; the famous “Laurel Brigade” under Brigadier General Thomas L. Rosser; and Brigadier General Matthew C. Butler’s brigade, which had just joined the army from the Charleston garrison. The men in this last unit, because it was armed with Enfield rifles—shorter versions of the infantry-issued rifled muskets—were more akin to mounted infantry than cavalry. Accompanying Hampton was a horse artillery battalion boasting 14 guns. A second division under Major General Fitzhugh “Fitz” Lee, Robert E. Lee’s nephew, was ordered to follow.

On the evening of June 10, Hampton reached a position three miles west of Trevilian Station. Fitz Lee’s smaller cavalry division—two Virginia brigades totaling 1,800 men—went into camp near Louisa Court House, eight miles to the east. Not content to await Sheridan’s next move, and despite knowing that he was outnumbered, Hampton decided to attack the next morning.

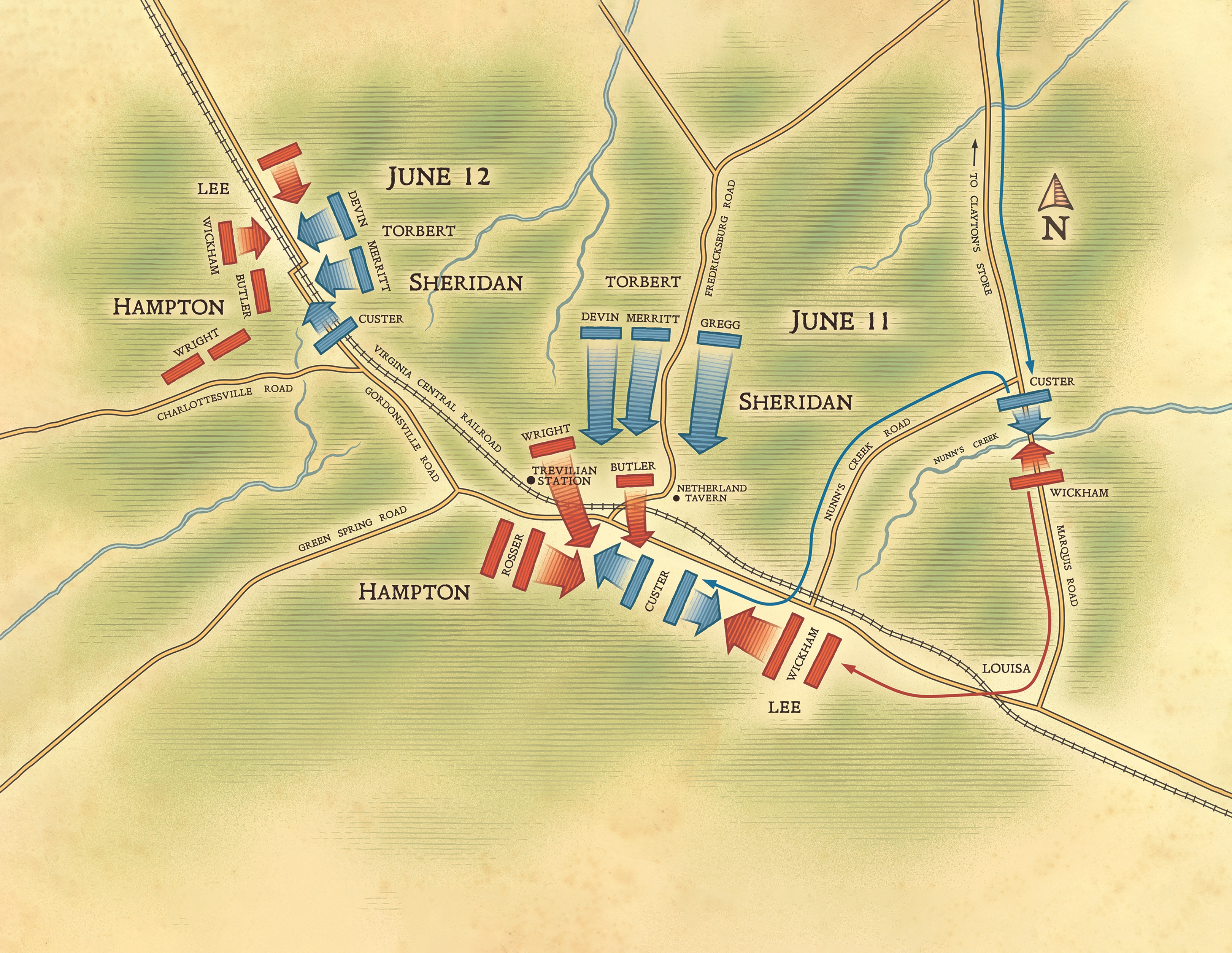

The first day of the battle was fought alongside an east–west stretch of the Virginia Central Railroad (and the Gordonsville Road that ran parallel to it) connecting Trevilian Station to Louisa Court House, four miles to the east, and along two roads heading north to Clayton’s Store (near Sheridan’s campsite). At Netherland Tavern, a two-story structure a mile east of Trevilian Station, the Fredericksburg Road plunged into the dense woods north of the iron rails and arrived at Clayton’s Store after wending a little over five miles. From Louisa Court House, the Marquis Road joined the Fredericksburg Road, just south of Clayton’s, after traveling north four miles. (These three main roads—Gordonsville, Fredericksburg, and Marquis—formed a rough triangle, with the Gordonsville Road as its base and Clayton’s Store its apex.) Along and to the south of the railroad the land was fairly open, but the area north of the tracks was heavily wooded, featuring only a few scattered farm fields. It was not well suited for mounted cavalry.

Early on the morning of June 11, Hampton, leaving Rosser’s brigade near Trevilian Station, marched north against Sheridan along the Fredericksburg Road with the troops under Butler and Wright. Fitz Lee was ordered to simultaneously attack north along the Marquis Road with his entire division. Sheridan’s two divisions at Clayton’s Store—still enjoying their morning coffee, the Confederates hoped—would thus be assaulted front and flank. “Hemmed in and crowded together, with a river in the rear,” wrote Confederate trooper Edward L. Wells, “[Sheridan] could then be destroyed.”

A mounted squadron of the 4th South Carolina trotted in advance of Hampton’s two brigades. Hampton had planned to surprise Sheridan, but the plucky Northerner was also on the move. When the troops made contact—prompting some frenzied shouting, an exchange of gunfire, and a brief mounted charge—Hampton dismounted Butler’s brigade and deployed it right and left. As the cavalrymen took to the woods as foot soldiers, horse holders—one man out of every four—led the riderless horses to the rear. “The ground was well chosen for the purpose,” Wells would later recall. “[The woods] would thus conceal [Confederate] numbers and dispositions…and in this way neutralize to a certain extent the greater effectiveness of the enemy’s magazine rifles.”

Because of the woods, the vicious fighting on either side of the Fredericksburg Road quickly devolved into confusion. Union captain Theophilus Rodenbough, commanding the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, wrote that his brigade, after driving in the 4th South Carolina, “advanced a quarter of a mile farther, when it found the enemy in force, dismounted, in a piece of timber, which extended across the road for some distance. Our cavalry was partly dismounted, and the entire First Division [under Torbert] became engaged.” Now, as the cavalrymen made their way through the woods on foot, ragged volleys ripped through the tangled underbrush. Shouted commands were barely audible above the din of carbine and rifle fire. Both sides kept some of their squadrons mounted, the occasional open farm fields witnessing the only mounted actions.

With Butler’s brigade under pressure, Colonel Wright’s brigade came up on its left, deploying with great difficulty. Artillery, too, got into the fight: Federal batteries unlimbered along a crest line and opened fire with shot and shell. Confederate artillery responded from a mile away.

On Hampton’s right, Fitz Lee was less than fully cooperative. He did dispatch a force north along the Marquis Road, and the movement took place before daylight, but he sent only one brigade under Brigadier General Williams C. Wickham, not his entire division. After this force captured a 7th Michigan scouting party, it continued north until it encountered an enemy picket line posted on the opposite bank of Nunn’s Creek. When Wickham’s halfhearted assault resulted in a considerable firefight, and Federal reinforcements arrived, the Confederate general had had enough. He broke off the action and retreated down the Marquis Road. So much for Wade Hampton’s two-pronged attack.

Fitz Lee’s failure to press the attack had a major impact on the course of the battle; it removed pressure from the Federal brigadier general at Nunn’s Creek: George Armstrong Custer. The 1861 West Point graduate had the perfect temperament for an outstanding commander of cavalry—the branch of the army that encouraged, indeed trained, its officers to be recklessly aggressive. He was nearly 6 feet tall, never weighing over 170 pounds. According to an army staff officer, Custer, with his hussar jacket, black velvet trousers, and straw-colored ringlet hair, looked “like a circus rider gone mad!”

Ordered to connect with the Federal forces pushing south along the Fredericksburg Road, Custer dashed down a little-used woods track that ran behind Nunn’s Creek to the Gordonsville Road. Not only did this lane bisect the two Confederate cavalry divisions—Hampton’s and Lee’s—but it also happened to be completely unguarded.

After just a short ride, Custer passed through the shielding woods and found himself a mile away from Trevilian Station—in General Hampton’s rear. In his immediate front sat Hampton’s ammunition and baggage trains, Butler’s and Wright’s horses, and the enemy riders who had brought them there for safekeeping. Without hesitating, Custer ordered the 5th Michigan Cavalry to charge. In the wild, running melee that followed they captured hundreds of prisoners, 1,500 horses, and almost 100 vehicles—wagons, caissons, and ambulances.

Unfortunately for Custer, however, some of his riders ranged too far west. Confederate brigadier general Rosser—a friend of Custer’s from West Point—trotted his brigade down from Trevilian Station and attacked the Federal riders with two of his lead regiments. “I went crashing into him, breaking up and scattering his squadrons,” Rosser later recalled. “Sitting on his horse in the midst of his advanced platoons, and near enough to be easily recognized by me, he encouraged and inspired his men by appeal as well as by example.” When his headquarters color sergeant was shot down, Custer tore the flag from its staff and thrust it into his jacket.

Hampton and Sheridan continued to slug it out astride the Fredericksburg Road, but the day’s most vicious fighting centered on Custer’s position. From the north, Hampton withdrew a part of his division and ordered it back to reclaim the baggage and ammunition train. Fitz Lee attacked Custer’s Brigade from the east. When Lee moved west along the Gordonsville Road, according to Rodenbough, he captured Custer’s wagon train and caissons, a spoil that included all of Custer’s previous captures (except 200 prisoners) and his headquarters wagon. Lee’s troops also took Eliza, Custer’s African American cook. (She later escaped, bringing Custer’s valise.)

With Lee’s division now sealing off the eastern flank, Rosser’s Virginians attacked from the west and south, and some of Butler’s South Carolinians moved in from the north. In the middle—in a position “very nearly a circle”—sat Custer and about 800 of his Michiganders. He was surrounded and outnumbered for the first time in his military career. Despite the seemingly dire situation, Custer’s troops did a superb job of holding on. The Southern forces had them trapped but could not overrun them. Undoubtedly, the firepower of the Michiganders’ Spencer repeating carbines greatly aided their defense.

Custer’s position was also bolstered by a battery, the 2nd U.S. Artillery under Lieutenant Alexander Pennington. And these unlimbered fieldpieces—less mobile than soldiers fighting mounted or on foot—frequently became the targets of enemy attacks. John N. Opie of the 6th Virginia Cavalry, Lee’s division, later recalled how his company and another, not more than 80 men, charged Pennington’s guns: “The gunners fled upon our approach,” he wrote, “and left us, apparently, for the moment, victors of the field, with the guns in our possession.” They continued their charge with weapons drawn until a mounted regiment came dashing from the woods on their flank and drove them away. Opie—“shot through the bridle hand and through the lung,” he wrote—fell into enemy hands.

Learning of Custer’s situation and hoping for a breakthrough, Sheridan reinforced his troops fighting along the Fredericksburg Road. Hampton sensed the buildup and withdrew. A brief lull followed. Then, in the afternoon, in one large simultaneous assault, three of Sheridan’s brigades—those under Brigadier General Wesley Merritt and Colonels Thomas C. Devin and J. I. Gregg—forced the Confederates past Custer’s encirclement and reestablished contact. General Merritt reported that “the enemy was driven…to Trevilian Station; but not without serious loss to ourselves, though we inflicted heavy punishment on the adversary.” In the Confederate retreat, hundreds of Southerners were forced into Custer’s lines and taken prisoner. The confused fighting of June 11 ended with Hampton retiring west. He was isolated from Fitz Lee’s division by Sheridan’s possession of Trevilian Station and the woods and fields surrounding it.

Rain fell the night of June 11. At Mallory’s Crossroads, about two miles west of Trevilian Station, Hampton regrouped his division. His losses were heavy, but he was determined to impede the enemy’s advance. That evening Sheridan learned that General David Hunter had failed to cooperate with the strategic plan. Instead of marching over the Blue Ridge, “Black Dave” had continued up the Shenandoah Valley to Lexington.

The morning of June 12, Federal horsemen tore up three miles of the Virginia Central between Louisa Court House and Trevilian Station. This work accomplished, Sheridan in the midafternoon sent Torbert west to feel out Hampton’s defensive position. Deployed between the roads leading to Charlottesville and Gordonsville, Hampton’s line was shaped like the number 7, the top bar comprising Butler’s brigade sheltered behind the Virginia Central embankment, facing northeast. The balance of Hampton’s force—using piled fence rails to commence their fieldworks—had dug in along the 7’s descender, facing southeast. Open farm fields to the front promised deadly work for the troops’ carbines. Unlimbered horse guns strengthened the line. Having circled south of Sheridan, Fitz Lee joined Hampton at this position, thereby providing him with a tactical reserve.

Torbert dismounted his troops and attacked on foot. Repeated Union assaults slapped against the Southern fieldworks. On the Confederate left, crouched behind the embankment, Butler’s Enfield-armed South Carolinians exacted a heavy toll. Merritt’s Brigade “went in on an open field to its right and attacked the enemy’s left flank vigorously,” Union captain Rodenbough noted. “It was slow work, however, and [the enemy] concentrated his force on the brigade, and gave the command as much as it could attend to.” When his right flank was threatened, General Merritt sent a mounted squadron—his last reserve—to cover it.

All afternoon the dismounted Federal assaults continued. A total of seven were counted. During one of the last attacks, Wells wrote, “One body marched…with beautiful precision, in close order, shoulder to shoulder, the rifles, Spencers or Winchesters, held horizontally at the hip and shooting continuously.” But when the unit’s leader was shot, Wells added, “immediately his men broke and ran.”

Torbert and Little Phil had had enough. As evening approached, Sheridan withdrew and began the trek back to the Army of the Potomac. He left behind about 100 wounded. Nearly 2,000 African Americans attached themselves to the retiring Union column. Hampton’s force was too shaken to immediately pursue. Both sides suffered heavy casualties for the two-day battle—955 Federals and 813 Confederates—but of course the South, with its smaller population, found its losses much harder to replace.

Both sides claimed victory. Northerners said that Sheridan had succeeded in drawing away most of the Confederate cavalry while Grant pulled off his scurry to the left. And the Federal raiders had destroyed a few miles of track. (The damage to the Virginia Central, however, was trifling.) Southerners countered that Hampton had stopped Sheridan cold; the former was obviously the better commander.

The first day’s fight was certainly a Federal tactical victory—as Custer was rescued from annihilation and the Confederates had withdrawn from the field—but the second day’s action was completely dominated by Wade Hampton. Hampton also scored the strategic victory. He’d handled his force superbly, outmarching Sheridan to get astride the Virginia Central ahead of him and ultimately denying him the two important railroad towns. Two months later, thanks to his performance at Trevilian Station, Hampton was made Lee’s chief of cavalry.

In 1866 Sheridan boasted that, following the Battle of the Wilderness, he and his cavalry “marched when and where we pleased; were always the attacking party, and always successful.” Yet he had concluded his Trevilian Station after-action report to Grant by stating, “I regret my inability to carry out your instructions.”

Over the years, Trevilian Station has been at the center of many exaggerated boasts. Confederate major Roger Preston Chew, who fought at Trevilian Station, claimed that the battle was one of the most important of the war because it preserved the railroad. “Trevilians was so important to General Lee,” Chew wrote, “that he was enabled thereby to stay in Petersburg for nearly a year longer.”

How much longer did the Confederate victory extend the war? It’s impossible to say. But Southerner George Neese, another participant, hit the nail on the head when he wrote: “It seems that Uncle Sam is depending on, and putting his trust in, the might of numbers to grind the armies and the rebellious Southland down by sheer attrition and brute force; consequently the powers that be at Washington select the commanders for their butting qualities instead of strategical capabilities.” The Southland could win victories like Trevilians, but that “grinding”—the war of attrition waged in Virginia by men like Grant and Sheridan—would ultimately seal the Confederacy’s fate. MHQ

Rick Britton, a historian and cartographer, lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.

[hr]

This article appears in the Autumn 2020 issue (Vol. 33, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Battle of the Mounts

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!