General Robert E. Lee wept when he heard that Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, his cavalry chief, had died, lamenting, “He never brought me a piece of false information.” Stuart was mortally wounded in combat at Yellow Tavern, Va., on May 11, 1864, and died at his brother-in-law’s house in Richmond the next day. “The Cavalry corps had lost its great leader the unequalled Stuart,” wrote a member of the 12th Virginia Cavalry. “We miss him much….Stuart’s equal does not exist.”

Stuart’s death left Lee in a quandary. Major General Wade Hampton III was nominally the senior of the three division commanders assigned to the Army of Northern Virginia’s Cavalry Corps, but a smoldering rivalry, even dislike, had been building between Hampton and Lee’s nephew, Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, Stuart’s subordinate. “The mantle of Stuart finally came to Fitzhugh Lee,” asserted a Confederate trooper. “This was but natural. Stuart and Fitz Lee had fought side by side, and planned cavalry campaigns together, and Fitz was Stuart’s trusted officer to carry out the boldest maneuvers. The cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia wanted no other leader than Fitz Lee after Stuart’s death.”

Hampton outranked Fitz Lee, however, only because his name appeared above Lee’s on the list of officers being promoted to major general in September 1863 (their dates of promotion were the same). Because of this conflict and tension, General Lee elected not to appoint a new corps commander and instead maintained the Army of Northern Virginia’s three cavalry divisions as independent commands, with each division commander reporting to him directly. This created its own set of problems, as there was no clear chain of command in the field.

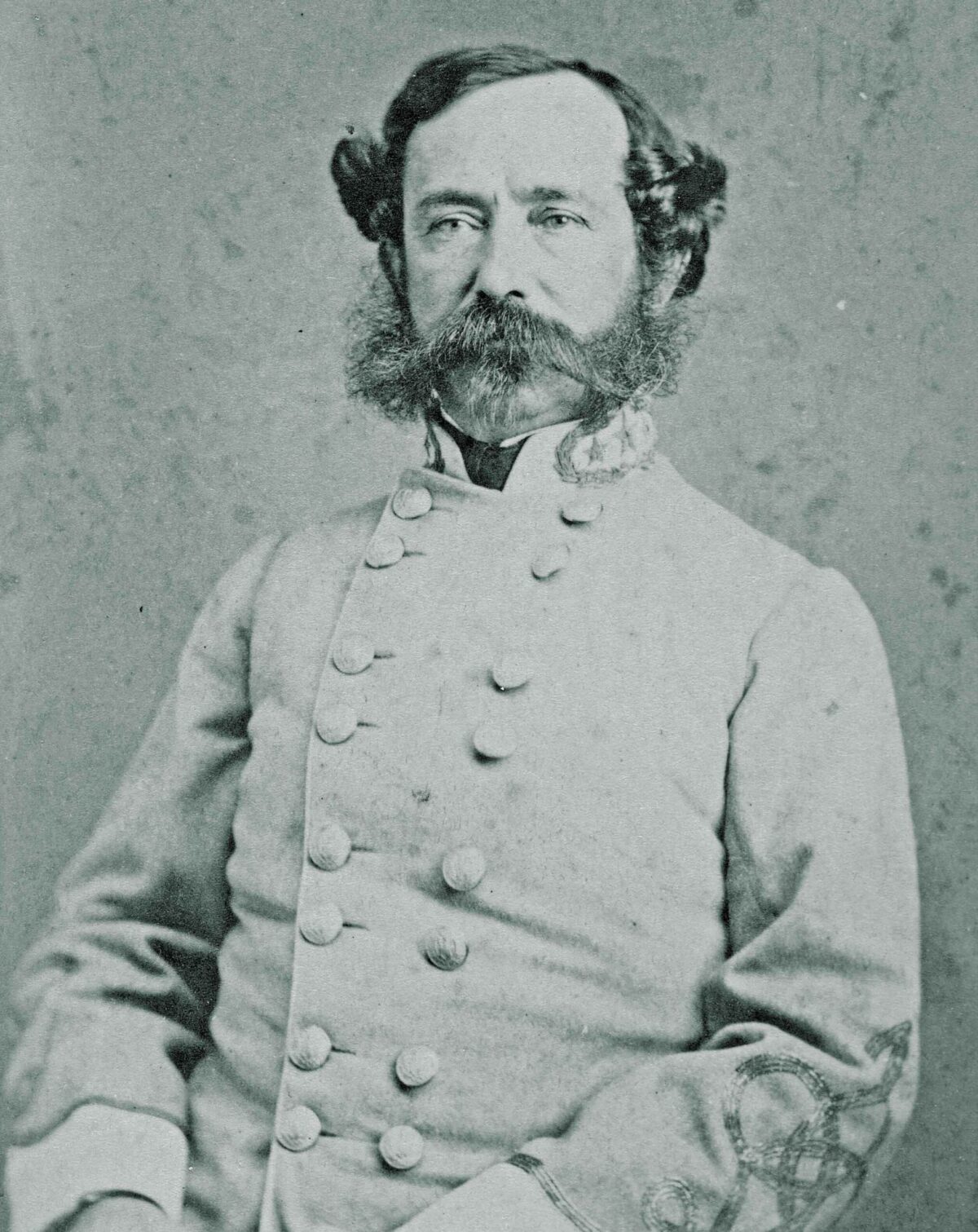

Hampton, at age 46, was one of the underrated heroes of the Civil War. The son and grandson of generals (also named Wade Hampton), he had no formal military training. Reputedly the wealthiest man in the South, Hampton had opposed the secession of his native South Carolina, but cast his lot with the Confederacy when the Palmetto State left the Union. He personally raised and equipped a combined arms unit called the Hampton Legion, and was wounded at First Manassas in July 1861 and badly hurt at Fair Oaks, Va., on May 31, 1862, while commanding a brigade of cavalry. Since he was neither a West Pointer nor a Virginian, he was always treated as an outsider, although no one disputed either his courage or competence. Utterly fearless, he was again severely wounded while leading a saber charge on East Cavalry Field at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. When he returned to duty that September, he was promoted to major general and assumed command of a division assigned to Stuart’s newly formed Cavalry Corps.

The Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, led by Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, left on a raid toward Richmond on May 9, 1864, with Stuart’s outnumbered troopers in pursuit. After defeating the Rebel cavalry at Yellow Tavern, mortally wounding Stuart in the process, the Union troopers on May 12 escaped from a trap Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry division had laid at Meadow Bridges, across the Chickahominy River to the east of Richmond. The Federals moved from there to relative safety at Yorktown, located on the Virginia Peninsula between the York and James rivers. They did not rejoin the Army of the Potomac until May 25.

By May 19, two weeks of brutal fighting at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House was nearly over. That day, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant ordered Maj. Gen. George G. Meade to move his entire army. On May 21, the Army of the Potomac attempted to cross the North Anna River, but without cavalry to lead the way, was thwarted by a stout Confederate defense at Ox Ford. Rebuffed, Grant withdrew.

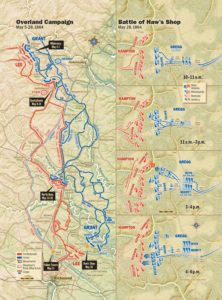

During the night of May 26-27, Grant dispatched two cavalry divisions and an infantry division east along the north bank of the Pamunkey River. On the morning of the 27th, these troops crossed the Pamunkey at Hanovertown and secured a bridgehead south of the river just 17 miles from Richmond. The rest of the Union army followed, crossing the Pamunkey on pontoon bridges on May 28. When Lee discovered that Grant was executing a turning maneuver, he marched the Army of Northern Virginia southeastward to interpose it between Grant and Richmond.

Uncertain of the whereabouts of Lee’s army, on May 28, Meade ordered Sheridan to “demonstrate” south toward Mechanicsville and the Chickahominy River. Several miles south lay the hamlet of Haw’s Shop, where John Haw III manufactured farming and milling machinery. Haw sold his equipment to the Tredegar Works in Richmond, but by 1864 his formerly thriving business lay in ruins. Salem Presbyterian Church and a few houses were all that remained. Still, the area was critical: Five roads, including two that led to Richmond, converged there.

The 1st New York Dragoons of the Reserve Brigade of the Union 1st Cavalry Division was already at Haw’s Shop, so Sheridan decided to use the adjacent fields as the staging area for his Cavalry Corps. At 8 that morning, he directed Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg to move his 2nd Cavalry Division to Haw’s Shop and hold it there “in readiness to make a reconnaissance.” The brigade of Brig. Gen. Henry E. Davies led Gregg’s advance to Haw’s Shop.

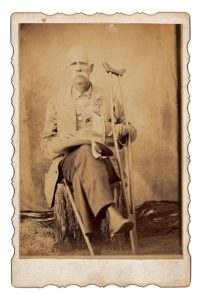

Hampton, with the brigades of Brig. Gen. Thomas L. Rosser (Hampton’s Division) and Brig. Gen. Williams C. Wickham (Fitz Lee’s Division) and followed by Maj. Gen. William H.F. “Rooney” Lee’s Division, spent the night of May 27-28 at Hughes’ Crossroads, about 15 miles from Hanovertown. Also accompanying Hampton’s command were nearly 1,000 men of a new brigade of South Carolina mounted infantry, raised and led by Hampton’s protégé, Brig. Gen. Matthew C. Butler, who had recently recovered from a horrible wound at the June 9, 1863, Battle of Brandy Station that had cost him a foot. Two of the new brigade’s three regiments, the 4th and 5th South Carolina Cavalry, joined Hampton on the afternoon of May 28. Butler had not yet arrived, however, meaning that Colonel Benjamin H. Rutledge of the 4th South Carolina led the greenhorns that day. The Confederate cavalry began marching at 8 a.m.

A clash at Haw’s Shop seemed inevitable.

The 10th New York Cavalry, of Davies’ brigade, led Gregg’s division along the Atlee Station Road to Haw’s Shop, while Hampton’s gray troopers quickly approached along the same road from the opposite direction, led by the 2nd Virginia Cavalry of Wickham’s Brigade. Colonel Thomas T. Munford, commander of the 2nd Virginia, sent about 20 troopers ahead to scout. Scouts of the 10th New York spotted the approaching Confederates and began firing. The Confederates charged, and the fight was on.

‘The Unseen Hand of The Great God’

Receiving promotion to the rank of corporal, Thomas W. Colley of the 1st Virginia Cavalry found great satisfaction in rejoining his comrades after a lengthy convalescence period. Left on the field for dead during the March 17, 1863, Battle of Kelly’s Ford in northern Virginia, he recovered miraculously from a near-fatal wound. Days after riding into the 1st Virginia’s camp, Colley saw action again during the May 24, 1864, engagement at Wilson’s Wharf/Kennon Landing; returning from this foray down the Tidewater peninsula, the troopers met a different force of Federals at Haw’s Shop.

The Battle of Haw’s Shop, which ended Colley’s military service, certainly left a lasting impression on the cavalryman. In his multivolume journals recounting military service and postwar life, Colley recalled the fateful day, May 28, 1864, when the troopers “moved rapidly forward towards Haw’s Shop…went in to line on the extreme left of our line…[and] dismounted as sharpshooters.” Colley detailed his unit’s various maneuvers as the action played out across the fields north of Richmond. We “closed upon them as we came in through a dense thicket of bushes and vines. We could not see or be seen until we came right up to the line, which was formed at a fence or rather two fences with a small space between them.” Colley’s time in the 1st Virginia drew closer to an end. “Two Yankee sharpshooters rose up from between these two fences and said, ‘Don’t shoot us we are your men,’ and our officers…commenced howling…not to shoot.” Next, “they both raised their carbines and fired into our ranks…and sprang over the fence as we all fired at them.”

An officer barked instructions for the Virginia troopers “to move up to the fence, [but] only six obeyed the order.” Because of the result, Colley could never forget the five troopers who joined him at the fence: “1st Sergeant Mike Ireson, Y.R. Pendleton, John G.R. Davis, S.D. Saunders, G.L. Clark, and myself.” Near the Federals, these six troopers hunkered down behind anything offering a degree of protection. We “were so close, their balls went over our heads; we were laying down flat on the earth with our carbines poked through the fence; breech loaders, [so] we did not have to withdraw them to load.”

As the fighting raged, Colley remembered occupying a forward “position one or probably two hours[,] when some of my companions behind me fired a shot that came near hitting me in the back of the head. I turned my head and yelled to them to quit shooting over me. It was not many seconds until another ball struck me ½ inch in front of my [left] boot heel and passed through the sole and up to the ankle bone.” After continuing to fire his carbine, the pain intensified. Finally, he decided to try to stand. “When I rose, the bones crushed, and I would have fallen to the ground had not two of my companions ran to me and caught me. They carried me up a slope of some 10 paces where the Yankee bullets had a fair sweep at us.”

Colley’s foot was amputated, but he would live another 45 years. Of his unit’s effort that day, he forever pondered: “How we all escaped without further damage I cannot conceive, it cannot be accounted for in any other way, only the unseen hand of The Great God who cared for us in our infancy.” —Michael K. Shaffer

Unsure the size of the Confederate force, the New Yorkers fell back to their picket line, pursued by the Southern horsemen. Munford brought up the rest of his regiment, and his troopers charged, driving the Empire State men back into the Haw fields. Davies ordered Colonel John P. Taylor’s 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry, just then arriving, to draw sabers and charge. Supported by dismounted carbineers of the 10th New York, the Pennsylvanians crashed into the Virginians in a scene that was “spirited in the extreme.”

Taylor’s Pennsylvanians drove Munford’s men back, with the stout post-and-rail fences on either side of the road funneling them into a tight formation that left little room for movement. “The 1st Pennsylvania never wielded the saber with better effect,” declared a trooper. The Virginians desperately tore down sections of the fence and fled in disorder, scattering in the woods near Enon Church. They built crude barricades while waiting for the rest of Wickham’s Brigade.

Davies deployed the rest of his brigade astride the road near Enon Church, facing the Virginians. Just then, Hampton and Fitz Lee rode up with the rest of Wickham’s Brigade. Hampton took in the scene unfolding in front of him and characteristically decided to stand and fight. He deployed the rest of Wickham’s regiments and the 7th Virginia Cavalry of Rosser’s Brigade and ordered them to charge. A captain, a lieutenant, and several troopers of the 6th Ohio Cavalry were killed during this attack. The rest of Rosser’s Brigade—which he later dubbed the Laurel Brigade—then fell in to the left of Wickham’s Brigade, extending the Confederate line to the north.

The fighting continued for several hours with both sides engaging dismounted, and both Union and Confederate horse artillery came up to support the cavalry. General Gregg established his headquarters in the Haw house, which soon saw duty as a field hospital. About 11 a.m., Hampton ordered Rutledge’s green South Carolinians to come up and take position to the right of Wickham’s Virginians, but they did not remain there for long—Hampton soon pulled them back and kept them in reserve. This was their first taste of battle, and the sights terrified them.

Now being pressed hard, Gregg committed his only reserves, the 1st New Jersey Cavalry, to the fight. He then sent word to Sheridan “as to how we stood, and stated that with some additional force I could destroy the equilibrium and go forward.” Union infantry was only a mile away, but Sheridan declined to request infantry reinforcements. For the time being, he left Gregg to his fate. Gregg decided to attack instead of allowing the Confederates time to dig in. The Jerseymen charged and filled a gap that had opened in the Union line, driving back the Confederate horsemen.

Fitz Lee ordered Colonel William Stokes and the 4th South Carolina forward again, taking position behind and to the right of Wickham’s right flank. The Palmetto men raised the Rebel Yell and charged to the east, their line of battle split by a ravine. At a range of about 50 yards, they traded volleys with the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry, and the battle devolved into a brutal slugging match in the dense woods. The South Carolinians, armed with muzzle-loading rifles, had the advantage of range over their opponents’ shorter-barreled carbines. “This continued for three quarters of an hour,” said a soldier, “the battle raging at its highest pitch conceivable, without intermission or cessation, but one continual roar of musketry, it seeming impossible that a man could escape.”

Hampton then committed Colonel John Dunovant’s 5th South Carolina Cavalry to the fight. It fell into line alongside Wickham’s troopers to the north of the Atlee Station Road and immediately opened fire at anything blue they saw. “The storm of lead became terrible,” wrote a New Yorker trooper. “It was at times the hottest place I ever was in. I had participated in engagements of greater magnitude, but never did I encounter in so short a space of time so much desperate fighting.” Dunovant was wounded in the hand during this heavy firing.

Responding, Colonel John W. Kester of the 1st New Jersey shifted a battalion of his regiment north of the Atlee Station Road to meet the threat posed by Dunovant’s troopers. Both sides took heavy losses, and the 5th South Carolinians did show their inexperience “by continually half rising to fire or to look at our line, thus giving our men an opportunity of which our marksmen took instant and fatal advantage,” noted a Jerseyman. The heavy fire pinned down the Palmetto men, preventing them from attacking the exposed position of Davies’ men.

The 1st Pennsylvania buckled under the pounding, but after being reinforced by three companies of the 1st New Jersey, the Keystone Staters attacked and broke Wickham’s line. Fitz Lee sent the 20th Georgia Battalion to reinforce the Virginians, and the position stabilized. The Confederates held their position in the face of severe attacks. Colonel John R. Chambliss Jr.’s brigade of Rooney Lee’s Division arrived to reinforce Hampton, taking position dismounted on the Confederate left.

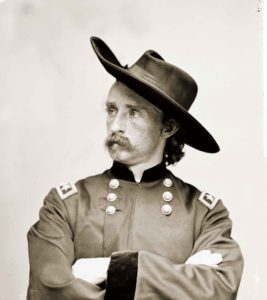

Sheridan also received reinforcements. Brigadier General Alfred T.A. Torbert’s 1st Division arrived, with additional horse artillery in tow. Troopers of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry of the Reserve Brigade and of Brig. Gen. George A. Custer’s Michigan Cavalry Brigade attacked Wickham’s and Chambliss’ positions until blistering fire from Wickham and Stokes’ 4th South Carolina halted their advance in its tracks and inflicted heavy losses on the Wolverines.

Chambliss came to believe Union infantry was arriving to reinforce Sheridan, and he reported this disturbing theory to Hampton. Hampton gave Chambliss permission to withdraw from his position on the northern end of the Confederate line just as a determined attack by Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt’s Reserve Brigade filled that gap. The Federals crashed into Rosser’s flank, driving his Virginians off. Their withdrawal exposed Wickham’s flank, compelling him to retire, too. Elements of the 2nd Virginia, 4th South Carolina, and 20th Georgia did not realize that Wickham had withdrawn, and they stood and fought, believing that they were not in danger of being flanked.

When Custer realized Hampton was withdrawing, he ordered a charge by the 1st and 6th Michigan. The Wolverines overran the Confederates who remained in their front, leaving the Georgians and South Carolinians almost completely surrounded. “We were outflanked and exposed to a terrific crossfire,” recalled a Palmetto trooper. Realizing the predicament, Fitz Lee ordered the Georgians and South Carolinians to withdraw. Hampton dashed out of the woods to help guide his men to safety.

The Wolverines continued pressing the retreating Rebels, joined by some of Gregg’s men. The retreat became a rout. “Had to cut our way out,” wrote a 2nd Virginia trooper. Lee ordered Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge’s infantry to come up to reinforce Hampton on the Atlee Station Road. Breckinridge’s troops dug in and provided cover for the defeated Southern cavalry, blunting any pursuit by Sheridan’s victorious troopers. The Battle of Haw’s Shop had ended.

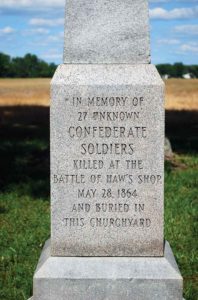

The battle was a “hard contested engagement, with heavy loss, for the number of troops engaged, to both sides,” Sheridan observed correctly. Hampton suffered 378 casualties, prompting a Richmond newspaper correspondent to declare, “Most of our loss is attributable to the fact that nearly all of the force engaged on our part were new men, whose only idea was to go in and fight, which they did most gallantly and creditably.” The Federals would lose 365.

Haw’s Shop marked the debut for the South Carolinians. But despite their inexperience, they fought long and hard, drawing praise from friend and foe alike. It also marked Wade Hampton’s debut as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Cavalry Corps. Although he made mistakes that day, he nevertheless managed both the battlefield and his troopers capably. In particular, Hampton demonstrated a mastery of dismounted tactics that made his troopers quite effective, and prevented the Union cavalry from achieving its primary goal: locating the precise position of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

Hampton and his green troopers would face the same two divisions at Trevilian Station on June 11-12, but this time it was an impressive Southern victory. Butler, now in field command of the South Carolinians, bore the brunt of the two days of brutal fighting at Trevilian Station, prompting Hampton to declare, “Butler’s defense at Trevilian was never surpassed.”

After Haw’s Shop, the Army of Northern Virginia’s Cavalry Corps never lost another battle with Hampton in command. Hampton proved himself a more than worthy successor to J.E.B. Stuart’s legacy. In February 1865, he was promoted to lieutenant general and became the highest-ranking officer ever in the Confederate cavalry service.

Eric J. Wittenberg, an award-winning historian, is the author of several Civil War titles, including Out Flew the Sabres: The Battle of Brandy Station.