For any shortcomings Union Maj. Gen. Julius Stahel may have had as an officer, his courage, at least, seemed beyond reproach. A native of Hungary, Stahel had served with the U.S. Army since the war’s outset, helping form its first German American regiment—the 8th New York Infantry—and then seeing action in the First Bull Run Campaign. Despite the Union setback at Cross Keys during Stonewall Jackson’s celebrated 1862 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, Stahel received regard as “brave and enthusiastic…seen during the day in the thickest of the fight, encouraging and urging on his men.” Further commendation would come in August for his efforts with the Army of Virginia at Second Bull Run—yet another Federal defeat in that calamitous second year of the war.

On May 15, 1864, the 38-year-old commander found himself engaged at the important Shenandoah Valley crossroads town of New Market. Serving as cavalry commander of Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel’s Department of West Virginia, Stahel was being counted on to play a prominent part in Ulysses S. Grant’s three-pronged conquest against Richmond that spring. As Grant’s Overland Campaign pushed through central Virginia toward the Confederate capital and Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler advanced up the Peninsula from Norfolk, it was the task of Sigel’s army to further disrupt the Rebel defenses and keep resources and reinforcements away from Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

Though relatively small in scale, the Battle of New Market was signature in many ways. Most famous were the contributions of the Virginia Military Institute’s Corps of Cadets, called into the fray out of desperation by Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge and ultimately playing a role in a stunning Confederate triumph. For Breckinridge, New Market would be a particularly welcome success, coming in the wake of hard-luck Western Theater setbacks earlier in the war at battles such as Stones River and Chattanooga. Breckinridge handled his force adroitly against Sigel’s vast army, nearly twice the size as his.

There were Union heroes, too: Medal of Honor recipient James M. Burns of the 1st West Virginia; Captain Henry A. du Pont, Battery B, 5th U.S. Artillery; Colonel Jacob Campbell, Lieutenant George Gageby, and Captain Edwin J. Geissinger of the 54th Pennsylvania—to name just a few.

What remains uncertain is how exactly Sigel allowed what probably should have been a comfortable victory get away from him. The incessant rain and stormy weather in which the armies clashed figured as major culprits, of course, as did Sigel’s seeming command complacency and lack of urgency in reaching New Market ahead of the Confederates. Breckinridge’s ability to do so allowed him to dictate critical aspects of the pending showdown.

Often overlooked in assessing the battle, however, is Stahel’s mindset on May 15 and how greatly it impacted the result. Early in the afternoon, even with the action unsettled and the weather worsening, Sigel’s significant advantage in numbers still offered promise of a Federal victory. Yet Stahel, his cavalry aligned a few miles behind the Union left flank on the Valley Turnpike, was growing increasingly restless. Not known as a bystander, the Hungarian finally decided that action was needed and ordered an ill-advised, full-blown charge. The domino effect from that would cost Sigel’s army dearly.

Cavalry had yet to be a major factor. Earlier in the day, Confederate Colonel John Imboden’s troopers had moved east of Smith’s Creek along with McClanahan’s Battery to enfilade the Union flank. Fire from McClanahan’s guns forced the withdrawal of Union cavalry and Alfred von Kleiser’s battery, but when Imboden later attempted to cross back across the creek to get behind the Federals, the swollen waters proved too great an obstacle.

“It was raining hard for the last hour, the ground was soaked, we were on low ground and there were puddles of water everywhere about us…,” grumbled Jacob Lester of the 1st New York Veteran Cavalry, adding that he and his comrades soon “got orders to ‘draw sabre’ and I knew we were to charge….Horses got stuck in the mud and fell over each other and in a moment we were mired up like a flock of sheep.”

The order from Stahel was in response to an apparent advance on his right by Confederate Brig. Gen. John Echols’ Brigade and the dismounted 62nd Virginia Mounted Infantry. As Sarah Kay Bierle posits in Call Out the Cadets: “Stahel decided the cavalry had been inactive enough for one day and concocted a grand scheme fit for a Napoleonic battlefield, but which would not translate well on the Valley Pike.”

Stahel, who had first gained notice fighting during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848-49, had long studied and admired such Napoleonic tactics, but the general clearly misjudged in believing an all-out charge on this terrain and under these conditions would succeed. In addition to the mud, a ravine with broken ground lay ahead of the Federal horsemen, and the Valley Pike (modern-day Route 11) featured low stone walls that would funnel them into a compressed front and leave them easy Confederate targets.

It is possible Stahel had no idea how great a threat he faced; even then, it might not have been enough to make him reconsider. The rain and low-lying battlefield smoke greatly hindered visibility, and Breckinridge—deducing a likely charge—had aligned his men perfectly. The Confederate position was formed into a defensive “V”: three batteries in the center, the 22nd Virginia Infantry on the left, and the 23rd Virginia Battalion on the right. (Jackson’s Battery was just west of the pike, positioned behind the 62nd Virginia.)

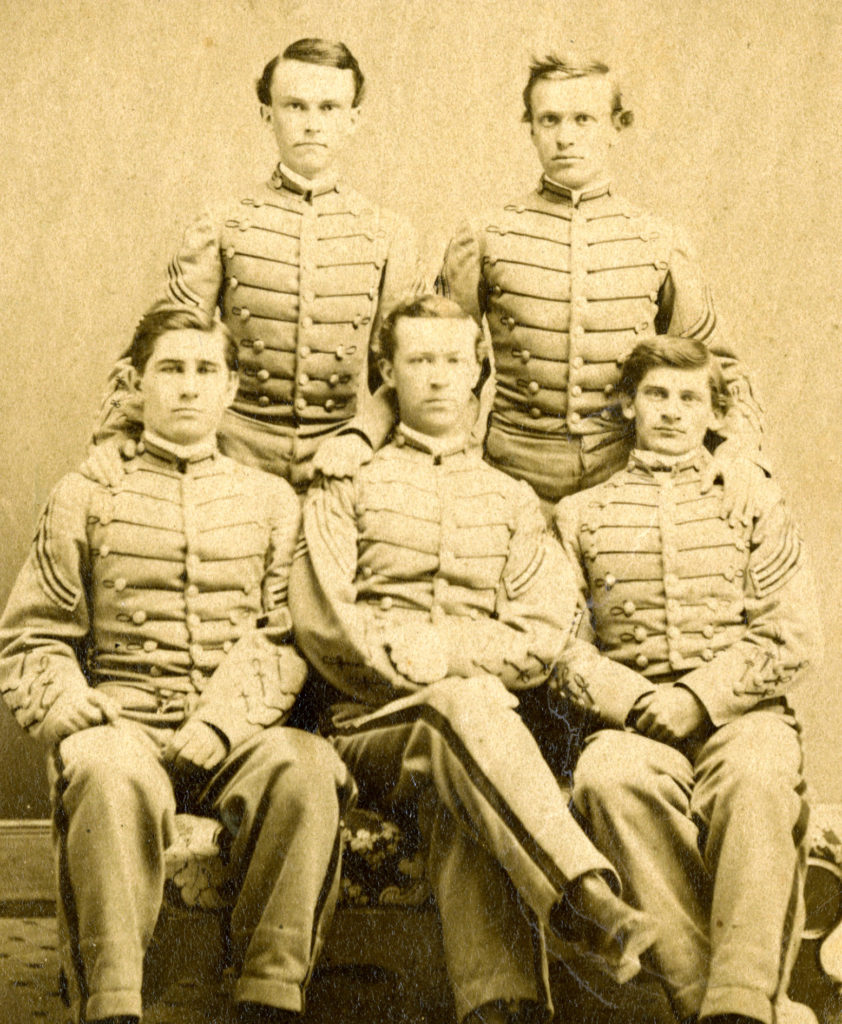

Included in the assembly of cannons on so-called Battery Heights were two guns manned by VMI cadets, lined up behind a partially demolished rock fence. Under the command of Lieutenant Collier H. Minge, a fellow cadet, they would be the first from the institute to see combat and would not disappoint, handling their guns like seasoned professionals. “We got quickly into action with canister…,” Minge recalled. “When the smoke cleared away the cavalry seemed to have been completely broken up.”

The collective Confederate firepower brought a quick end to Stahel’s brazen charge. Stahel had sent forth roughly 1,000 horses, but the lead elements never got close to the Confederate guns, cut down en masse in the middle of the road. As Rand Noyes of the 22nd Virginia later wrote: “Only one man on an unmanageable horse came through….” The 1st New York rallied for a second attempt, but was quickly undone by friendly fire.

“They were ready for us,” lamented Sergeant William A. McIlhenny of the 1st Maryland (U.S.) Potomac Home Brigade, also known as Cole’s Cavalry. “Our battalion marched directly into their artillery fire. Shells were dropping all around us and musket balls were whistling. The rebels were so close that we could see their long grey line of infantrymen advancing. Where were our regiments of infantry?

“The rebel infantry was nearing gunshot range. Just as they started firing a regiment of our men arrived. We fell back for them to form in line. But it was too late! The rebels were upon us, firing at close range. They mowed our men down like grass. Our cavalry tried to keep together, but were impeded by the retreating infantry men escaping from the hot fire of Breckenridge’s pursuing men. Many of them didn’t escape. All the way to the Shenandoah River they were hot on our heels.”

Recalled Lester: “A shell from the rebel artillery struck a man at my side carrying away half of his head and spattering his brains, hair and whiskers all over the right side of me. The same shell carried away the left shoulder and arm of a man in front of me and struck another man farther on square in the back, passed through and as he toppled from his horse I saw his whole front torn open and a torrent of blood flowing from it.”

In a June 1908 letter to Confederate Colonel George M. Edgar, Minge reminisced about the remarkable history his cadets had made:

“[W]e were hurried down to position No. 3 on the right and just off the turn-pike road….Here we got quickly into action with cannister against Cavalry charging down the road and adjacent fields. I think all the guns [Major William] McLaughlin had were thrown down to this point. I believe the Artillery aided the Infantry very materially against this last bold move of the enemy. When the smoke cleared away the Cavalry seemed to have been completely broken up, and we saw no more of them to the close….

“I have heard that the conduct of the boys composing the Section was commended both by Gen. Breckinridge and the Major. Dear Old Col. [William Henry] Gilham said some nice things about us, but his love for us would have overlooked our faults if we had committed any. Major Thomas M. Semmes of the Institute…was charged with the responsibility of seeing that we did not run away, and I have been told that he also had some very kind words for us.”

McIlhenny had questioned the absence of Union infantry support during the failed cavalry attack. As it turned out, the 54th Pennsylvania Infantry was nearby, positioned next to the Valley Pike on terrain Minge referred to in his letter as a “dale”—featuring rolling hills and a group of low cedar trees. Aligned to the 54th’s immediate right was the 1st West Virginia Infantry, which in turn was flanked by the 34th Massachusetts Infantry. The dreadful conditions and battle chaos, however, created uncertainty for all three of those regiments, and uncoordinated advances starting after 3 p.m. would turn particularly dire for the 54th Pennsylvania.

Earlier in the war, the 54th had seen duty primarily in defense of a stretch of the B&O Railroad between Cumberland, Md., and what would become Martinsburg, W.Va. New Market would be one of the regiment’s first true engagements and it would hit the Keystone State boys hard. In approximately two hours of fighting, the 54th suffered 174 casualties—nearly 31 percent of its 566-man strength. To their credit, the Pennsylvanians remained engaged for some time before being forced to retreat from the field.

At one point, Sigel’s Union lines had stretched roughly more than a mile west from Smith’s Creek to the North Fork Shenandoah River, just north of Jacob Bushong’s prosperous farmstead. The fighting had progressed west following Stahel’s failed charge and the 54th Pennsylvania’s struggle on ground to be labeled “The Bloody Cedars.” A Federal position on a rise next to the river, however, remained relatively strong, manned by the artillery units of Captains Alonzo Snow, John Carlin, and Alfred von Kleiser as well as elements of the 34th Massachusetts and 1st West Virginia.

Sigel wanted the 54th Pennsylvania, 1st West Virginia, and 34th Massachusetts to advance in junction. That would not happen. The 1st covered about 100 yards before falling back, leaving the 54th and 34th isolated on its flanks.

When a gap opened in the Confederate line around the Bushong Farm, fear grew that the Federals would exploit it. To this point, Breckinridge had held the cadets in reserve, reluctant to send them in. Urged on by an aide, Major Charles Semple, he finally relented: “Put the boys in, and may God forgive me for the order.”

The cadets’ advance down an incline toward the Bushong House began ominously, as a Federal shell exploded in their midst, killing three: William Cabell, Charles Crockett, and Henry Jones. Fears that the cadets might run were promptly put to rest, though, even after another cadet, William McDowell, was shot and killed and several others were wounded.

The VMI boys joined the line of Brig. Gen. Gabriel C. Wharton’s Brigade around the Bushong Farm. Their position was receiving steady fire from von Kleiser’s batteries as well as the 34th Massachusetts and 1st West Virginia.

A stealth advance along the river by members of the 51st Virginia and the trailing 26th Virginia put Snow’s and Carlin’s guns in jeopardy, however, and fire from the Confederate right produced significant Federal casualties.

The 300 or so yards of elevated ground that directly separated the cadets and von Kleiser’s guns were caked with ankle-deep mud—no deterrent in the least, it would prove. Their bayonets fixed, the cadets suddenly surged forward. Even when several lost their shoes in the muck and were forced to proceed barefoot, the momentum was unstoppable.

Likewise impeded by the muddy terrain, von Kleiser’s uneasy men struggled to shift back the battery’s six guns. When the relentless cadets overran his position, von Kleiser would lose one of his guns. He then was forced to abandon a second, its wheels mired in the mud.

The Union position atop the ridge collapsed and the fraught Federals retreated toward Mount Jackson, eventually crossing the North Fork of the Shenandoah and burning the lone bridge there to stop short the pursuing Confederates. It had been a spectacular, well-deserved victory, but for the triumphant Confederates, it would only delay the inevitable.

A few days later, Grant removed Sigel from command. In June, Sigel’s replacement, Maj. Gen. David Hunter, torched the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington before advancing toward Lynchburg. Stahel continued as commander of the department’s cavalry, and his efforts at the Battle of Piedmont on June 5 earned him a wound and a Medal of Honor. He resigned from the Army in February 1865.

Union Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan eventually assumed command of what became the Army of the Shenandoah and unleashed a campaign of devastation upon the region’s bountiful agricultural resources—“The Burning,” as it was infamously known in Southern hearts. Sheridan’s victory at Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864, marked the effective end of any Confederate military hopes in this once-critical theater of war.

Chris Howland is editor of America’s Civil War.

Call to Arms! The Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation (SVBF) is working to preserve the 52-acre Battery Heights tract on the New Market Battlefield where the VMI artillerists fought during the May 1864 battle. Call the SVBF at 540-740-4545 or visit Shenandoah at War for more information. Donors of $500 or more will receive a limited-edition canvas giclee of Keith Rocco’s “They Were Ready for Us” painting, as seen at the top of this article. (A closer look at the creation of Rocco’s painting can be found in the Autumn 2022 print issue of America’s Civil War.)