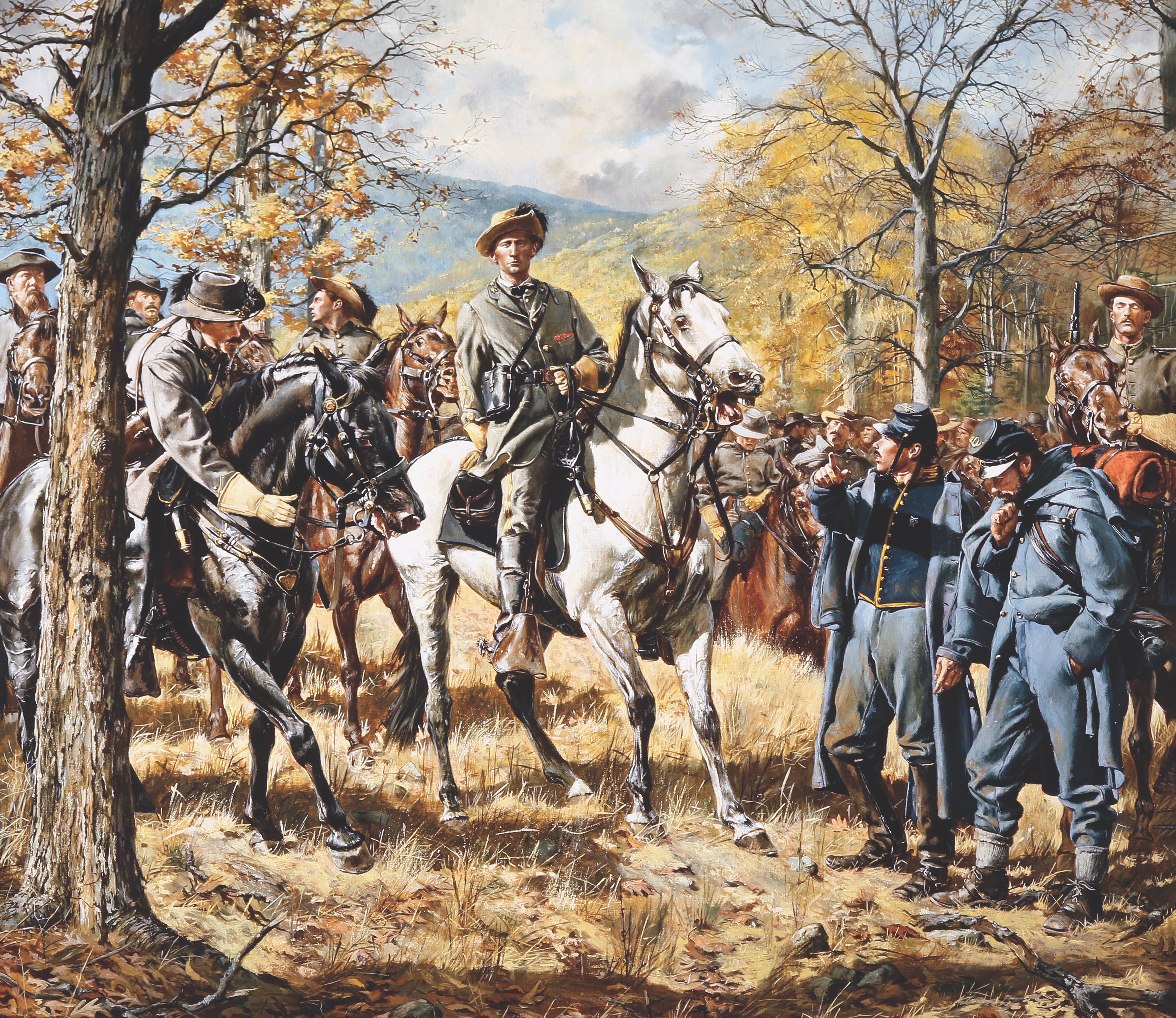

In late December 1863, Confederate Maj. John Singleton Mosby and his 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry were operating in and around Loudoun County in Northern Virginia. At the same time, Union Maj. Henry A. Cole was conducting patrols and raids in the same region with his 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion, Potomac Home Brigade, better known as “Cole’s Cavalry.”

A clash of some sort between the two enemy units was inevitable, and, in fact, three short yet brutal engagements would occur over the first seven weeks of 1864.

The Fights Begin

The series of showdowns began Dec. 30, as Capt. Albert Hunter and about 60 members of Cole’s Cavalry departed their Loudoun Heights camp near Harpers Ferry, West Virginia., on a patrol toward Rectortown, Virginia. As his troopers advanced south into “Mosby’s Confederacy” — an area encompassing Virginia’s Loudoun, Fauquier, Clarke, and Warren counties — Hunter knew it was likely his adversary would soon receive reports of his venture.

Hunter’s patrol spent the first night in Lovettsville, about 10 miles southeast of Loudoun Heights. The next morning as they continued to push south, the weather turned increasingly wretched. Low temperatures chilled the men — and snow, sleet, and rain soaked both them and their equipment. The men found some protection from the elements at a farm and rested New Year’s Eve in tolerable comfort.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Bitter New Year’s

When the troopers awoke the morning of Jan. 1, they were greeted with sunny but cold weather. Mounting, they continued heading in the direction of Middleburg, where the New Year’s Day calm was disrupted by a brief skirmish with some of Mosby’s Rangers. One Union trooper, Pvt. Jason McCullough, was wounded, but Hunter’s men captured three Rebels. Hunter decided to send McCullough and the three prisoners back to Loudoun Heights with a small escort. The remainder of the detachment continued toward Rectortown, just south of Middleburg.

New Year’s Day also marked a rendezvous of some of Mosby’s men, and, as fortune would have it, Rectortown was their destination, too. Upon their arrival on the outskirts of town, the Rangers, commanded by Capt. William “Billy” Smith, were surprised to discover the presence of Hunter’s detachment. Smith ordered his men to watch their foes’ activities, but to avoid an engagement.

Hunter, though, had seen the shadowy figures of the Rangers, about 30 total. Concerned their numbers might continue to grow and satisfied the mission to reach Rectortown had been completed, Hunter decided a return to the main Loudoun Heights camp would be the most prudent option. Hoping, however, to confuse his enemy of his actual destination, Hunter initially moved south toward Salem (today’s Marshall) before turning north to head back to camp.

The Rangers followed Hunter’s troopers and quickly saw through their deception. Smith directed his men to cut across nearby fields to get in front of the Federal force. Three Rangers comprised Smith’s lead element: Richard Paul Montjoy, Henry Stribling Ashby, and John Carter Edmonds, all eager to engage the enemy. Coming upon the rear of Hunter’s formation near an intersection of five roads, known by the locals as “Five Points,” they attacked. Smith heard the noise of the initial assault and hastened the rest of his command forward to join the fray.

His horse killed, Hunter would be captured early in the clash, and though the Union troopers momentarily held their ground and blunted the Rangers’ initial assault, their defense soon collapsed. Realizing their leader was now out of the fight and that their revolvers wouldn’t fire because of damp powder, they lost all semblance of military discipline and rode off in fear and panic.

Hard Riders in Blue

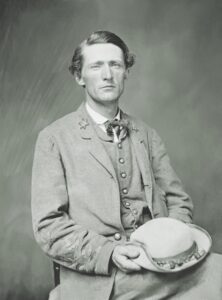

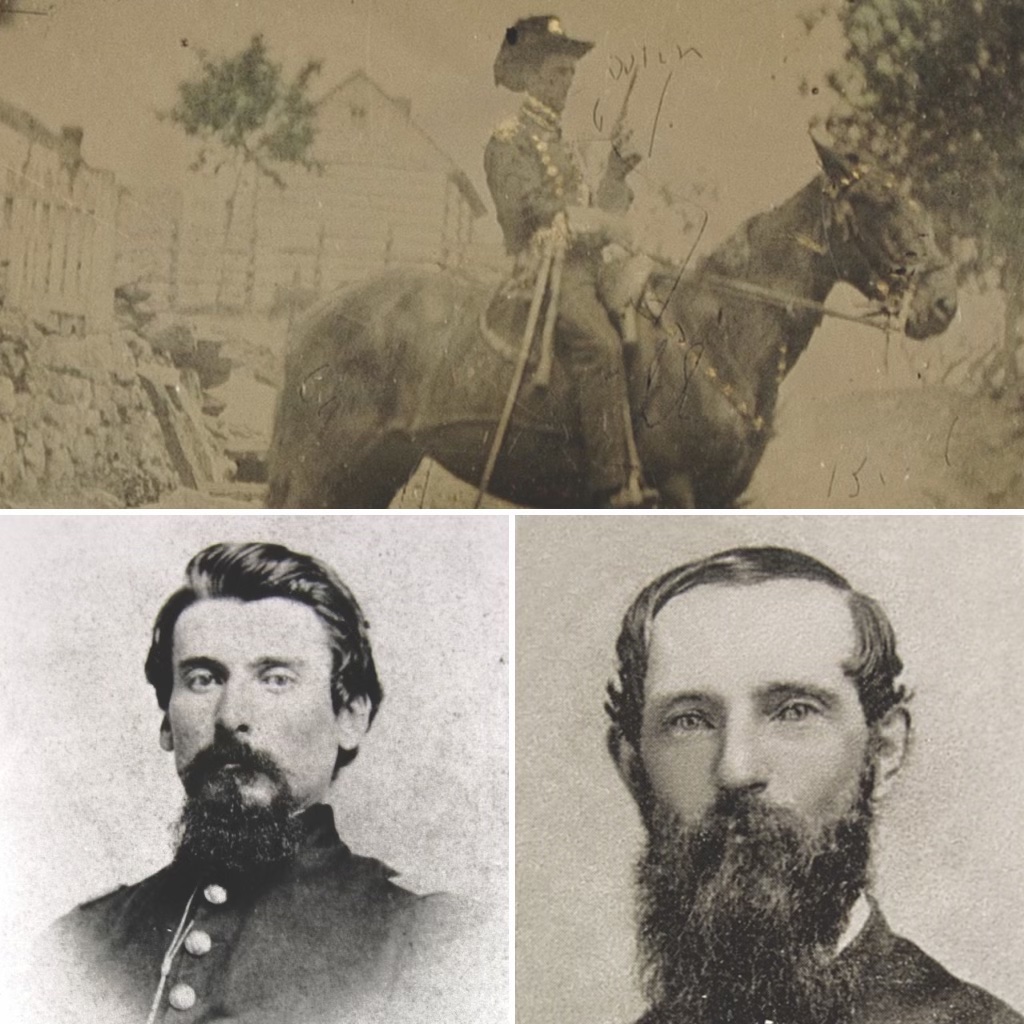

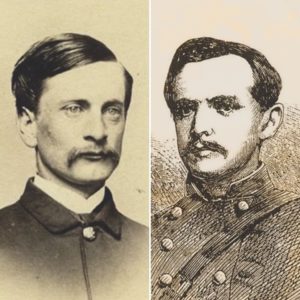

Top: An ambrotype of 2nd Lt. Samuel B. Sigler, Cole’s Cavalry, on his horse “Bill.” Above left: Captain Albert Hunter proved one of Cole’s most dependable subordinates, serving until he mustered out in June 1865. In 1890, he would write a four-part personal history of the war. Above right: Henry A. Cole enjoyed a steady rise in command with the 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion, Potomac Home Brigade, after joining as captain of Company A in August 1861. He was promoted to major when the 1st was consolidated as a battalion in August 1862 and then to colonel in February 1864.

Firsthand Account

Describing the “Five Points Fight” in a letter to the Richmond Times-Dispatch — published nearly 50 years later, on Feb. 16, 1913 — Ranger Thomas William Smith Lake wrote:

[O]n January 1, 1864, a detachment of Cole’s Battalion, composed of a detail of twenty men from each company, numbering in all about eighty men, under command of Captain A.N. Hunter, came in a search from Harper’s Ferry of Mosby’s men….We had orders to meet in Rectortown that day….We got off on a hill and watched their movements when our men began to gather in. Finally, Captain Smith came in, and with about twenty men we followed in the rear to near a place called Five Points, a place where five roads converged. We had gathered there twenty-eight men. Captain Smith said, “What shall we do, fight them or not?

Captain Hunter had time to form his men in a field that once belonged to my father; or, in other words, we were on our own dunghill and felt a good deal like fighting. Just as we reached the top of the hill in sight of their column, Captain Smith was on the left, and I on the right in the first set of twos. Captain Smith jumped his horse over a gap on the left; the enemy was on our right side. But it was not long before I had a companion brave as the bravest, John Gulick, by my side, and we made straight at them, receiving a galling fire, and they stood till we could see the whites of their eyes, and going up to them, Gulick was shot in the shoulder. But they could not stand those Indian yells and soon broke and ran. There was a marshy place just in their rear they knew nothing about and ran into that. A good many got unhorsed and were captured there. Then we had a running fight for some six or seven miles, in which they used their drawn sabres to put more motion to their horses, a good many of which gave out and they were captured….”

The Federal casualty count was dreadful, with at least four killed and another dozen wounded. Various reports listed 30–40 Federals captured, what was perhaps the worst defeat for “Cole’s Cavalry” the entire war. (A sobering postscript to the fate of the Union men captured that day reveals that 24 later died in Confederate captivity. Hunter was not one of them, however, as he had escaped his captors while the battle swirled around them.)

The Rangers, meanwhile, came through the New Year’s fight virtually unscathed, with only two wounded. The first Mosby–Cole engagement had been a lopsided victory for the man to become known after the war as the “Gray Ghost.” The tables soon turned, however.

Another Engagement

On Jan. 7, Confederate scout Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Stringfellow informed Mosby that he had conducted a reconnaissance of Cole’s Loudoun Heights camp and that he believed a surprise raid on it was certain of success. Mosby and Stringfellow had served together earlier in the war as scouts for Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, with the two holding an abiding trust and respect in each other. Based on Stringfellow’s report and recommendation, Mosby agreed to meet him near Cole’s camp on January 9 to conduct the raid.

Gathering about 100 men, Mosby left Upperville and proceeded to the northeast. The weather was frigid and the temperature continued to drop as the men headed toward their objective. Further exacerbating the already cold conditions, a brisk wind made the ride almost unbearable and the men stopped twice to warm themselves. The first respite was at “Woodgrove,” home of James Heaton, whose son, Harry, rode with Mosby; the second at St. Paul’s Church on the Harpers Ferry Road. The Rangers welcomed the breaks from the cold, though any feelings of warmth were fleeting. Ranger accounts of the ride to Loudoun Heights describe men having to dismount and walk to prevent their feet from freezing. While walking, many also slipped their hands under the saddle blankets of their mounts to regain feeling in their fingers. The demanding trek clearly degraded the men’s mental alertness and physical dexterity.

Despite the circumstances and punishing weather, Mosby and his men remained undetected and met with Stringfellow a few miles from Loudoun Heights. Stringfellow had gone ahead to scout the enemy camp and reported that all was quiet within. The raid appeared destined for success.

Caught Napping

Following a route suggested by Stringfellow, Mosby circumvented Union pickets and moved closer to Cole’s position. The raiders continued moving without detection, even when they had to negotiate a steep climb in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Forced to dismount and lead their horses, men slipped and fell, resulting in such nerve-wracking commotion that their stealthy approach seemed in jeopardy. Yet all remained quiet within the enemy camp site.

Finally gaining a position from which they would attack, the Rangers had literally caught Cole’s Cavalry napping. In his report of the raid, Mosby would write: “On reaching this point without creating any alarm, I deemed that the crisis had passed and the capture of the entire camp of the enemy a certainty.”

Preparing to launch his strike, Mosby gave Stringfellow and his small band of scouts the honor of attacking the house on Loudoun Heights where Cole had his headquarters. Within minutes of Stringfellow’s departure, however, everything unraveled. As Stringfellow’s little detachment closed in, a shot echoed in the dark. Whoever fired that solitary round was never determined, but bedlam immediately erupted inside Cole’s camp, spurring Stringfellow’s men to pull away with much greater noise and recklessness than they had during their approach. Their retreat took them directly into the path of the Rangers, who had been ordered hastily forward by Mosby because of the shot. Believing they were being attacked by Cole’s men, those Rangers fired directly at Stringfellow’s men, leading to a number of friendly fire casualties. Mosby’s surprise and certainty of victory had vanished in an instant.

Disoriented by the commotion, Cole’s troopers poured out of their tents just as Mosby’s men surged into their camp. Although the half-dressed, some barefoot, and bleary-eyed Federals were at first confused, they quickly steadied themselves and unleashed a shower of carbine and revolver fire into the midst of the Rebel intruders. One quick-minded Union soldier, never identified, called to his comrades to shoot anyone who was mounted. That command and subsequent lethally accurate fire from the Union troopers was devastating. Highlighted against the dark night sky by the glow of burning tents, Mosby’s men were unmistakable targets.

The snow covering the campground was quickly stained with blood. Mosby soon realized his situation was untenable, any recent thoughts of victory replaced by the knowledge that he had to promptly extract his beleaguered men to avoid further loss. He ordered a withdrawal. For a unit used to prevailing with minimal casualties in such confrontations, the Rangers soon faced the sad truth that five men had been killed and six wounded. Three of the six wounded later died from their wounds. One Ranger was captured.

Among those killed in the Loudoun Heights clash was “Billy” Smith, who only days before had performed so magnificently at Five Points. Lieutenant William Thomas “Prince George’s Tom” Turner was mortally wounded, dying a week later. Both were favorites of Mosby and highly respected and revered by their comrades. In writing about them later, Mosby cited them as “two of the noblest and bravest officers of this army, who thus sealed a life of devotion and of sacrifice to the cause they loved.” Not surprising, in his report about the disastrous raid, while still pained by the deaths of Smith and Turner, Mosby wrote that his losses were “more so in worth than the number of the slain.”

Remembering the win

One of Cole’s troopers, C. Armour Newcomer, recounted the Union victory in his “Cole’s Cavalry; or, Three years in the Saddle in the Shenandoah Valley”:

“Colonel Mosby, their old antagonist…had crossed the mountain and fell upon the camp, and then fired a volley into the tents where Cole’s men lay sleeping, many of them no doubt dreaming of their sweethearts and loved ones at home. No one who has not experienced a night attack from an enemy can form the slightest conception of the feelings of one awakened in the dead of night with the din of shots and yells coming from those thirsting for your blood. Each and every man in that attack, for the time, was an assassin. But we should remember that war means to kill; the soldier in the excitement of battle forgets what pity is, and nothing will satisfy his craving but blood.

The rude awakening brought Cole’s hardy veterans out into the deep snow covering the mountain, and they promptly picked up the gauge of battle. Long experience in border warfare had taught these gallant Marylanders to shoot at the horsemen, and not attempt to mount their own faithful chargers….

During the fight every man was for himself. There was no time to wait for orders, the cry rang out on the cold frosty air “shoot every soldier on horseback.” Many of the Confederates who were killed or wounded were burned with powder, as Cole’s men used their carbines. It was hand to hand, and so dark, you could not see the face of the enemy you were shooting. It was a perfect hell!….

Mosby had been badly used up; our comrades who had lost their lives on the last New Year’s day, and in other engagements, where he had been defeated, were now avenged. It was difficult to tell how many had been lost until after daylight.”

PAYBACK

For the Rangers, the bitter loss at Loudoun Heights dramatically overshadowed their Five Points triumph. One engagement between the two forces remained, however. On Feb, 20, Maj. Cole and 200 troopers departed Loudoun Heights on another scouting expedition into Mosby’s Confederacy. Reaching Upperville, they surprised and captured 11 Rangers.

Mosby, staying a few miles away, promptly learned of the Union incursion and dispatched a few men to alert the other Rangers in the area to the threat and to order them to assemble as rapidly as possible. As Cole’s men continued south to Piedmont Station (today’s Delaplane), the Rangers mounted and set off to rendezvous with their commander.

After reaching Piedmont Station, Cole decided to return to Upperville and then, ultimately, Loudoun Heights. By that time, Mosby had assumed a position where he could both maintain surveillance on Cole’s element and await the arrival of more Rangers. When Cole turned his men around and began his return trip to camp, Mosby followed. Soon, small groups of Rangers had joined Mosby, and when he reached the outskirts of Upperville, the major had gathered nearly 50 men.

Seeing that Cole had stopped his men in the little town to water their horses, Mosby decided to attack. Unprepared to receive an enemy charge, the Federal troopers were quickly pushed out of the town, pressed by the Partisan Rangers. During the pursuit, Pvt. Montjoy engaged and killed one of Cole’s officers, Capt. William L. Morgan, in an informal duel. “Montjoy earned his bars today!” Mosby would exclaim, officially promoting him to captain a few weeks later.

Cole tried to hold his men together as they fell back to their camp, but the Rangers’ pressure was relentless. Finally, he rallied his men behind the protection of a stone wall near Blakeley’s Grove School. There, the steadfast Cole hoped to make a stand and drive Mosby away. The tactic was initially successful as multiple charges were stifled. But Mosby, seeking an advantage, ordered some of his men to attack Cole’s flank. Suddenly confronted by enemy from two directions, Cole and his men were forced from their position. The Federals lost any semblance of an organized delaying action, their sole mission now an escape from the onslaught and a safe return to their camp. After harrying Cole’s men for a few more miles, the Rangers broke off the chase, satisfied with their victory.

Blakeley’s Grove School marked the last fight between Mosby’s and Cole’s men. Despite victories there and at Five Points, the painful losses Mosby suffered at Loudoun Heights could not be forgotten. Indeed, as he had stated, the loss of “quality” that day left a void never fully refilled.

AFTERMATH

Mosby, eventually promoted to colonel, continued operating in northern Virginia for the duration of the war, remaining an annoyingly persistent and painful thorn in the side of Union commanders. Cole also achieved the rank of colonel, and his 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion grew into a regiment. After the Blakeley’s Grove School fight, Cole’s Cavalry commenced operations in the Shenandoah Valley as part of the greater Union effort there.

In 1895, Mosby penned a heart-felt, cordial reply to an invitation to attend a reunion of Cole’s Cavalry:

“I did not receive until too late your polite Invitation to attend the reunion of Cole’s Cavalry. It would have given me great pleasure to meet my old antagonists around the festive board, but it is now too late for me to make arrangements to go or to give notice to the members of my old command of your invitation to them. I give you the assurance of my best wishes.”

Eric Buckland retired from the U.S. Army as a lieutenant colonel after spending the majority of his 22-year career in Special Forces. An officer of the Stuart–Mosby Historical Society in Centreville, Virginia, Buckland has written several books and frequently delivers presentations focused on the “men who rode with Mosby.” He can be contacted at info@mosbymen.com.