Although not the biggest battle the Australians experienced, Long Tan was perhaps their most desperate and critical fight in Vietnam

On the late afternoon of Aug. 18, 1966, Australian Maj. Harry Smith and the men in his Delta Company faced a vastly superior force of 2,500 heavily armed Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army troops at an abandoned rubber plantation near Long Tan, a village about 40 miles southeast of Saigon. Against all odds, the Australians held out for more than three hours until reinforcements arrived. The 108 men of D Company, 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, fought for their lives in the pouring rain as ammunition dwindled, casualties mounted and the enemy massed for a final assault. There seemed to be no way the Aussies could survive the onslaught.

The Battle of Long Tan was the most important engagement of Australia’s involvement in Vietnam, which began in July and August 1962 when 30 military advisers from the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam arrived to work with the American contingent of military advisers assisting South Vietnam’s armed forces in their fight with the NVA and Viet Cong. In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson asked nations across the globe to join the U.S. military effort to prevent a communist takeover of South Vietnam. Australia and New Zealand were among the countries that sent a substantial combat force.

A total of 60,000 Australians served in Vietnam between 1962 and 1973, with a peak strength of 7,672 in 1969. These troops included ground, air force and naval personnel. By the time Australia’s troops were removed from Vietnam in 1973, Australia had suffered 521 killed and about 3,000 wounded.

New Zealand sent 3,890 troops to Vietnam between 1964 and 1972, with a peak of 552 in 1969. The casualties included 41 killed and more than 180 wounded.

In May 1966, Australia dispatched to Vietnam the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, which was temporarily attached to the American 173rd Airborne Brigade in Bien Hoa province, bordering Saigon.

A typical Australian battalion had 37 officers and 755 enlisted men, spread among a headquarters group, four rifle companies (Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, Delta), a support company and an administration company. Each rifle company ideally had 123 men: five officers and 118 enlisted. However, it is unlikely that the battalions were ever consistently at full strength. There were personnel shortages because of illness, leave, casualties and gaps between the end of some tours and the arrival of replacements.

Each soldier carried at least 150 rounds of ammunition in addition to his weapon. The standard issued rifle was the British Commonwealth’s L1A1 self-loading rifle. Starting in 1966, the American M16A1 rifle became available, and some Australians shouldered those as well. Other items carried by Australian troops included an entrenching tool, machete, bayonet, at least one M26 grenade, nine full canteens of water and five days’ worth of rations.

Each 10-man section shared the load of ammunition and a spare barrel for the M60 machine gun, the M79 grenade launcher, extra grenades, Claymore mines (remotely detonated mines that spray steel pellets) and extra radio batteries. All of those weapons and equipment were used by D Company in its desperate holdout against VC and NVA forces.

The 6th Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment arrived in South Vietnam in May 1966 and joined the regiment’s 5th Battalion at Nui Dat in Phuoc Tuy province, which included Long Tan. From June to August the 6th Battalion took part in Operation Enoggera, a search-and-clear mission at Long Phuoc. The men also participated in Operation Hobart, a five-day search and destroy mission. During Hobart, the battalion made its first contact with the Viet Cong’s Mobile Battalion D445—a unit the Australians would encounter again on the fateful day in August.

For days leading up to Aug. 18, the headquarters at Nui Dat had picked up radio transmissions and other signs indicating a large VC and NVA force was within 3 miles.

On Aug. 16, the 5th Battalion patrolled an area north of the Australian task force base. At the same time A Company of the 6th Battalion patrolled the area north and northeast. Intelligence reports estimated enemy strength as 300 to 3,500—a range so large that it was an essentially meaningless number. Most patrols reported contacts with groups of three to six men, typical for the VC.

Getting a fix on the enemy force was crucial because the Australian base camp at Nui Dat was in poor condition due to the monsoon weather and could be easily overrun. The rain made visibility practically nonexistent, and the ground turned into an oozing red mud that made maneuvering difficult.

In the early morning of Aug. 17, 1966, the communists attacked. Enemy mortar and recoilless rifle fire struck Nui Dat. The defenders responded with return fire from base artillery and the attack caused only limited damage. However, the 1st Australian Task Force commander, Brigadier Oliver David Jackson, realized the vulnerability of his base.

After the attack, B Company of the 6th Battalion conducted a sweep of the area east-northeast of Nui Dat to determine the location and size of the enemy force and to retaliate against the perpetrators. However, the Australians found nothing but abandoned firing positions. At 10:35 a.m. B Company reported the discovery of a dug-in pit large enough to hold about 20 men and evidence of a 75 mm recoilless rifle that was fired at the base camp. At 12 p.m. a B Company patrol following the enemy’s escape trail came across another recoilless rifle position and evidence of at least two wounded VC, who had likely been injured by Australian artillery counterfire.

D Company relieved B Company on Aug. 18 at 1 p.m. As B Company returned to Nui Dat, D Company continued the search for signs of the enemy but didn’t expect to find much. Based on intelligence at the time, recounted D Company leader Smith, “my commander indicated a weapons platoon and protection, perhaps 50-60 VC, probably long gone. No indication was given to me of any larger force in the area.”

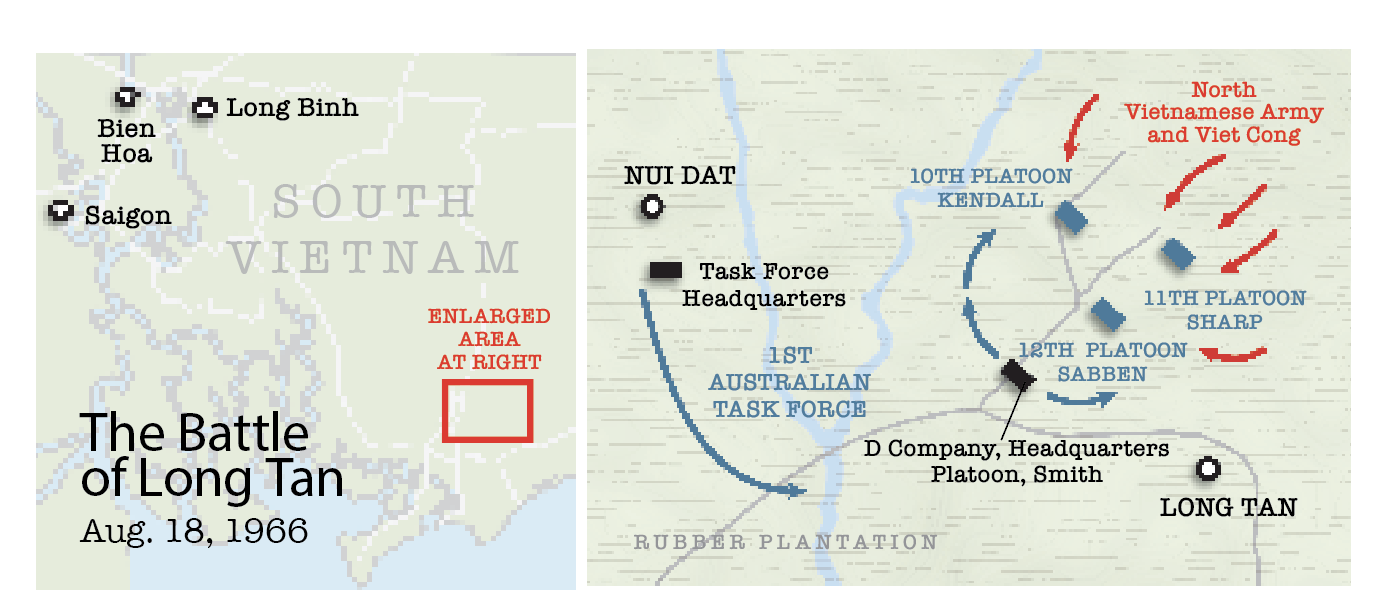

D Company followed a series of parallel cart tracks leading from the base camp into an abandoned rubber plantation near Long Tan. The Australians made their way through the plantation with 11th and 10th platoons in the front, followed by the 12th Platoon and D Company’s headquarters platoon. On the right front was 11th Platoon under the command of Lt. Gordon Sharp. The 11th Platoon made contact with a small force of Viet Cong about 3:30 p.m. After a short firefight, the VC disengaged and fled east.

D Company’s troops moved into the rubber plantation and soon realized they had stumbled upon the enemy’s lair. Sometime around 4 p.m., 11th Platoon was hit with heavy fire from multiple directions as the enemy attacked with rocket-propelled grenades. Several soldiers were hit, and the rest were pinned to the ground. Sharp reported contact with a platoon-sized enemy. The lieutenant did not yet know the tremendous force he had come up against.

Realizing the enemy’s number was much larger than he could have imagined, Sharp quickly changed his assessment, reporting a company-sized enemy directly in front. At the same time, 60 mm mortar shells rained down on the 10th, 12th and Headquarters platoons.

Smith immediately moved those elements north and away from the mortar blasts. Artillery support was called for and 11th Platoon was ordered to disengage. However, it was too late—the platoon was outflanked and unable to withdraw. Sharp was killed.

Sgt. Bob Buick took command of the already battered 11th Platoon. The Headquarters Platoon included three New Zealand artillery forward observers from the 161st Field Battery, Royal Regiment of New Zealand Artillery: Capt. Maurice Stanley, Bombardier (artillery rank equivalent of corporal), W.G. Walker and Lance Bombardier N.N. Broomhall. The forward observers called in and adjusted enemy fire to support the infantrymen under attack.

Following the attack, 10th Platoon, in the front left position under the command of Lt. Geoff Kendall, was ordered to assist 11th Platoon. Despite taking heavy casualties, 10th Platoon got within 100 yards of 11th Platoon before its men were stopped by intense small-arms fire. Adding another tragic twist to an already bad situation, an intense storm rolled in. This reduced visibility and made it difficult to identify targets. But there was an even bigger problem: 10th Platoon no longer had a functioning radio.

The 10th Platoon’s radio and radio operator were hit early on, according to Cpl. Graham Smith, who was first radio operator for company commander Smith. Headquarters Platoon’s second radio operator, Bill Akell (a private nicknamed “Yank” because he was born in Boston), grabbed a spare radio and “charged towards 10 Platoon, killing two VC on the way,” according to radioman Smith. This act of bravery reestablished communications between D Company’s 10th Platoon and its Headquarters Platoon.

Kendall was ordered to withdraw 10th Platoon and rejoined Headquarters Platoon. This was accomplished under the cover of allied artillery fire. Lt. David Sabben, commanding 12th Platoon, took two sections of his platoon west in an attempt to reach 11th Platoon from a different direction. Sabben’s men also encountered heavy fire and could not reach the trapped platoon.

In essence, D Company was being surrounded and broken into separate groups with each one taking heavy fire. At 5:10 p.m. D Company reported the enemy was 200 yards in front. The 11th Platoon was in the worst trouble. It was being attacked from north, east and south. An hour and a half had passed since first contact with the enemy. More than half of 11th Platoon’s 28 men were killed or wounded within the first 20 minutes.

As 10th Platoon withdrew and the Australians planned another attempt to help their trapped comrades, the VC and NVA forces closed in around the struggling remnants of 11th Platoon. The communist troops hoped to wipe out D Company one small piece at a time—starting with the unfortunate 11th Platoon.

However, 11th Platoon was able to hold on and “never lost radio communications, not until withdrawal when their radio operator was killed,” headquarters radioman Smith recalled. As the NVA and VC advanced on the 11th Platoon, New Zealand gunners of the 161st Field Battery began “walking” their artillery fire, moving it closer and closer to the pinned-down Australians to blast the enemy troops as they drew near. Some shells fell “danger close” (less than 100 yards from the Aussies). The artillery unit’s success in walking shells so close to friendly troops indicates that the radio operator must have been feeding coordinates to the gunners the entire time.

At about 4 p.m. on Aug. 18, the first reports regarding the attack reached the base camp at Nui Dat. Within minutes artillery from three batteries of the 1st Field Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery, and one battery of the American 2nd Battalion, 35th Field Artillery Regiment, fired on the communist attackers, using coordinates provided by the New Zealand forward observers attached to D Company’s Headquarters Platoon. Those guns fired continuously, dropping almost 3,500 rounds on the enemy. Lt. Col. Colin Townsend, commanding officer of the Australian 6th Battalion, estimated 50 percent of the VC killed were eliminated by artillery.

Three F-4 Phantom II fighter-bombers of U.S. Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 542 arrived for airstrikes but had trouble identifying targets because of the rain. Two Royal Australian Air Force UH-1B Huey helicopter pilots from the 9th Squadron were able to come in low and drop boxes of ammunition to D Company. B Company was ordered back to Long Tan to reinforce D Company. Additionally, Australia’s 3rd Troop, 1st Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, loaded A Company soldiers into 10 vehicles and set out for Long Tan. But would they get there in time?

Around 6 p.m., the 11th Platoon’s survivors were able to pull back and make their way to 12th Platoon. Tragically, in this withdrawal the radio operator who played a vital role in the platoon’s survival was killed. About half an hour later, the combined 11th and 12th platoons were able to regroup with the rest of D Company.

Using whatever cover was available, the Australians in D Company deployed in a defensive position and prepared for the onslaught they knew was to come. Smith had two platoons, the 10th and 12th, at about 75 percent effective strength and one platoon, the 11th Platoon, all but noneffective. All ammunition was distributed to everyone who could still fight.

At dark, the enemy assault began. For the next 30 minutes or so, there was no reprieve as D Company repelled wave after wave of attacks. Suddenly at about 7 p.m., the foot soldiers of B Company and the personnel carriers transporting A Company arrived almost simultaneously. The .50-cal. machine guns of the personnel carriers blasted through the surrounding rubber plantation. The enemy scattered, ending the Battle of Long Tan as quickly as it had started.

Townsend ordered D Company back to the western edge of the plantation, and the wounded were evacuated. Over the next two days cleanup operations were carried out across the battle area. All the Australian dead and wounded were recovered. In total 18 Australians were killed—17 from D Company and one from the 1st APC Squadron. More than 20 were wounded and taken to field hospitals for treatment.

More than 245 communist soldiers were found dead on the battlefield, but captured documents suggest hundreds more had been killed or wounded. The exact number was impossible to determine because the communists typically removed their dead and the impact of the high explosive artillery rounds that struck the battlefield left little evidence of what had been there before.

In an area no bigger than two football fields the men of D Company, 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, faced a much larger force and yet survived against 20-1 odds. Even so, the fight of Long Tan is considered the costliest battle for the Australians during their entire time in Vietnam.

Sabben, the commander of D Company’s 12th Platoon, summed up the battle this way: “Long Tan wasn’t the biggest battle the Australians experienced. It didn’t last the longest. Nor did it involve the most troops. But it was perhaps the most desperate, the most critical to the Australian mission, and certainly it was the most decisive in terms of results.”

Dana Benner holds a master’s degree in heritage studies. He teaches history, political science and sociology on the university level. Benner served more than 10 years in the U.S. Army. He lives in Manchester, New Hampshire.

This article appeared in the December 2020 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here: