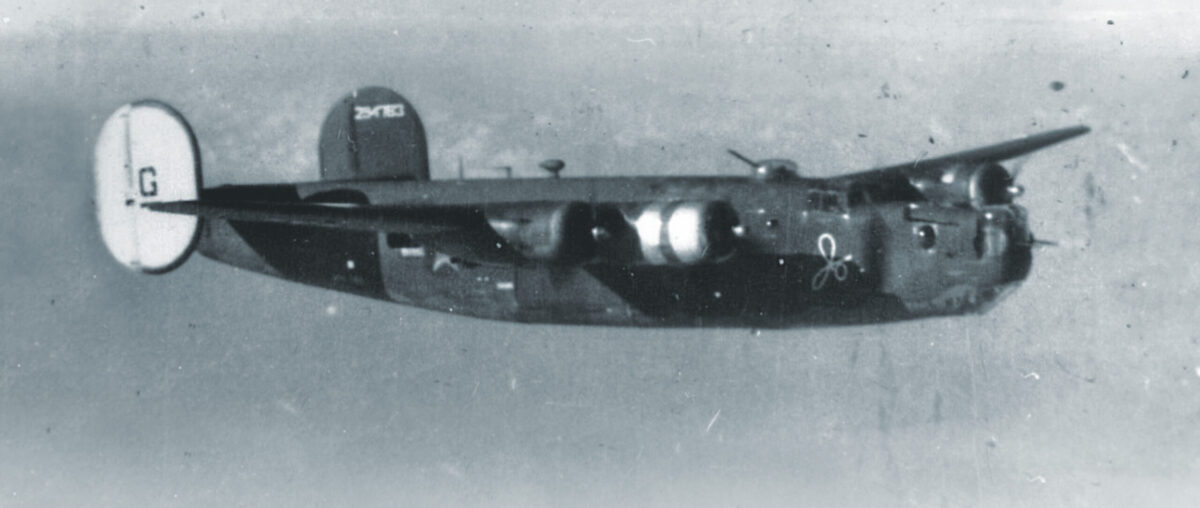

The cold blue sky was spattered with red bursts and puffs of anti-aircraft fire on July 7, 1944. Downward streaks of black smoke to our front marked the demise of both Allied and Axis aircraft. Chaos drew closer and closer as our B-24 Liberator hummed onward. From my copilot’s seat, I squinted through the windshield to gauge the approaching whirlwind. Distant German planes were at first no larger than tiny specks whizzing through our advanced formations. Having just kicked the enemy’s nest, we were soon to be engulfed by an angry swarm.

Moments prior, we had dropped our payload on the morning’s target—a Junkers aircraft plant in Aschersleben, located in the north-central region of Nazi Germany. Our Second Air Division dropped over 200 tons of incendiary and high-explosive bombs on that plant. Ordnance plowed into the factory with devastating impact. On a larger scale, more than 1,100 American heavy bombers took off that morning to strike eleven priority targets throughout the Reich. The assault was the biggest aerial blow since D-Day.

A voice shouted over the intercom, “Bandits! One o’clock!”

Rapid flashes of yellow and orange suddenly appeared to our front. In a matter of no time, the enemy was among us.

My mind raced. “Stay focused,” I told myself. “There’s no time to be scared up here. Do your job.”

As many as 200 Messerschmitt fighters engaged us in a death struggle four miles above earth. They spewed red sheets of fire in swift succession. My heart raced at the sight. Veteran crews quickly realized the Germans had changed their tactics. Rather than charging at us obliquely, the enemy sped to the front of our formation and charged head-on—going down our line of four or five air groups at 400 miles per hour, twice the speed of our planes. The scene resembled a massive domino effect. Squeezing the triggers of their powerful 20mm cannons with each pass, oncoming Germans could hardly miss. Minus brief pauses for cooling, their heavy guns could unleash 700 shells per minute. The enemy put these weapons to shocking use.

One of my comrades later referred to the sudden onslaught as “a huge ball of German fighters.” Bandits screaming forward at closing speeds of 600 miles per hour were the stuff of nightmares. White gun flashes dotted the sky. Deathly volleys had the capacity to shred our 37,000-pound Liberators to pieces. With crazed determination, Jerries sometimes pressed their assaults within yards of our aircraft. I maintained a tight grip on the controls, doing my best to concentrate amid the struggle.

In hot pursuit of the enemy was an array of American fighters assigned to protect those of us in the heavies. Among the support squadrons were vaunted P-51 Mustangs, now known as “Cadillacs of the Sky” for their sleek design and astounding velocity of up to 440 mph. The arrival of these long-range fighters we referred to as “little friends” was a form of deliverance. When Mustangs emerged, Nazi fighters sometimes dispersed to prey on vulnerable bombers with less protection. These prompt reinforcements helped level the playing field and led to a swirl of dogfights. Flyboys corkscrewed in and out of the clouds at a dizzying pace.

At the nose of our plane, Sgt. George “Bill” Puska blared away at oncoming intruders with hefty twin .50-caliber machine guns. Tracer rounds fired in short bursts allowed for aiming correction and served as targeting markers for five fellow gunners onboard. Cabin floors were littered with small mountains of spent, sizzling brass. I hardly heard any of the racket with the constant whir of the twin Pratt & Whitney engines I could see outside my window. In this frenzied environment, gunners set their targets with extreme precision to avoid instances of friendly fire. Our Mustangs or P-47 Thunderbolts could be misidentified even at close range. The ability to distinguish friend from foe was essential.

As copilot, I kept watch on other planes in formation. If my skipper was wounded or killed, command passed to me. I hoped that would never be the case. The main pilot carefully observed instruments and control panels. His primary duty was to take our plane to a target and back safely. Both our jobs in the cockpit were exceedingly technical. The operation of our equipment required constant attentiveness. If I made a mistake, it could be fatal.

I spoke into my throat microphone, “How’s everybody doing?” If one of the crew didn’t answer, I sent another man to check him. Communication and teamwork were fundamental to our endurance. The emergence of the Luftwaffe that summer morning put us to the ultimate test.

The fight lasted perhaps eight minutes. Despite the tempo of combat, time seemed to slow as we tried to escape. One by one, Jerries eventually peeled from the engagement. No longer hunted by German interceptors, many a battered ship staggered the 450 miles back to base. Surviving aircraft rumbled through Holland, toward the Channel, and on to England. Thankfully, I somehow remained cool and composed through it all.

Our crew was luckier than many. A group flying adjacent to us lost all eleven crews of its lower squadron. Over 100 men were gone in a matter of minutes. To our immediate right was Lt. Frank Fulks, piloting the high squadron’s lead plane. His aircraft suffered several hits on the nose and top turret from 20mm cannons. His ship was in a shambles. Fulks’s navigator and bombardier were seriously wounded as well. The pilot fell out of formation for a brief time and then took position on our wing, remaining there until we reached home.

All the while, we fell into dire straits ourselves. Our number three engine failed just before we crossed back over the German border. Although the B-24 could still fly with one engine out of commission, the malfunction made a difficult day even more harrowing. We were certainly not alone in our predicament. The bomb group endured many difficult landings that afternoon.

During the stressful return flight, my eyes were drawn to the top of Fulks’s battered plane. The sight has never left me.

The turret was shattered and caved in. The gunner’s head had been ripped away by the brute force of the explosion that claimed his life. The wind of the slipstream had siphoned his blood across the plane’s exterior surface. The top fuselage was painted with ghastly red streaks all the way to the tail.

It was the goriest sight I’ve ever seen in my life.

To cope with this horror, I tried erasing the memory. My job required so much concentration that I couldn’t dwell on such scenes.

That operation marked just my second journey into combat. When we returned to quarters that night, we discovered our names listed on the board for the next day’s mission. “Oh, Jesus Christ,” we collectively moaned. The deathly cycle was already reset for morning, but I was too exhausted to contemplate matters of life and death. I collapsed into my bunk and promptly fell asleep. Over the next four months, there would be many more missions to fly, many more targets to bomb, and many more friends to mourn.

Adapted from Into the Cold Blue: My World War II Journeys with the Mighty Eighth Air Force by John F. Homan with Jared Frederick (Regnery History, 2024). Available on Amazon.