The B-17’s four engines hummed in Sergeant Elmer Ruschman’s ears on the morning of June 6, 1944, as he wondered whether the ominous clouds concealing the English Channel below would lift in time for the 429th Bomb Squadron’s assault on German pillboxes lining the Normandy coast. The 23-year-old radio operator had grown accustomed to flying in volatile weather the previous summer as the Flying Fortress crew practiced bombing runs over the wheat and mustard fields of northern Montana.

My eyes are also fixed on the sky as U.S. Highway 2 winds east down from the Rocky Mountains, fewer than 50 miles south of the Canadian border, and drops me in the rolling plains of the 1.5-million-acre Blackfeet Indian Reservation. On a clear day, a driver approaching Cut Bank International Airport—where Ruschman’s squadron trained—can spot the 60-foot-tall octogenarian airplane hangar from at least five miles out. Today, mid-April flurries obscure the view, and I miss my turn to the airport.

I turn around at Cut Bank Creek, named by Meriwether Lewis, who admired the 150-foot cliffs etched by the elements above the riverbanks when he passed through here in 1806 to confirm the northern boundary of the Louisiana Purchase. Forty-nine years later, this Missouri River tributary became the eastern border of the Blackfeet Reservation. After the Great Northern Railway laid tracks over the creek in 1890, a small town sprang up on the east side as a commercial hub for regional farming and ranching. The community of Cut Bank thrived through the Great Depression due to an oil and gas boom and, in June 1941, opened Montana’s first international airport, three miles southwest of town, on private land within the reservation boundaries.

I pull into a gravel stall marked “long-term parking.” Roy Nollkamper, retired airport manager and cofounder of the Cut Bank Airmen’s Memorial Museum, welcomes me inside the modest terminal. Built in 1949 during the airport’s passenger service heyday, today it serves daily United Parcel Service runs and occasional private or medical flights. A young pilot with time to kill browses the impressive collection of arti-facts that volunteers have amassed in the terminal’s tiny diner-turned-museum. A pair of Norden bombsights, practice bomb casings, and a B-17 cockpit window narrate the story of a far busier season.

When the United States entered World War II, the heavily armed and notoriously sturdy Boeing B-17 was the long-range aircraft of choice to bomb enemy supply lines and support Allied ground forces. While Boeing began churning out more than 12,000 of the heavy bombers, the army looked for sparsely populated places to train the 10-man crews who would fly them. Northern Montana fit the bill nicely.

On July 6, 1942, the U.S. 2nd Air Force approved plans to construct an air base at Great Falls, Montana, with satellite airfields in Cut Bank and the fellow small towns of Lewistown and Glasgow, forming a rough triangle with a 300-mile hypotenuse. Four-squadron B-17 groups would be assigned to Great Falls, with one squadron from each group based there and the other three distributed among the satellite bases. Pilots, bombardiers, radio operators, engineers, and gunners would arrive at their assigned airfields fully trained in their specialties and learn to fly as crews, practicing long-range navigation and bombing in the landmark-less prairie before crossing the Atlantic for combat.

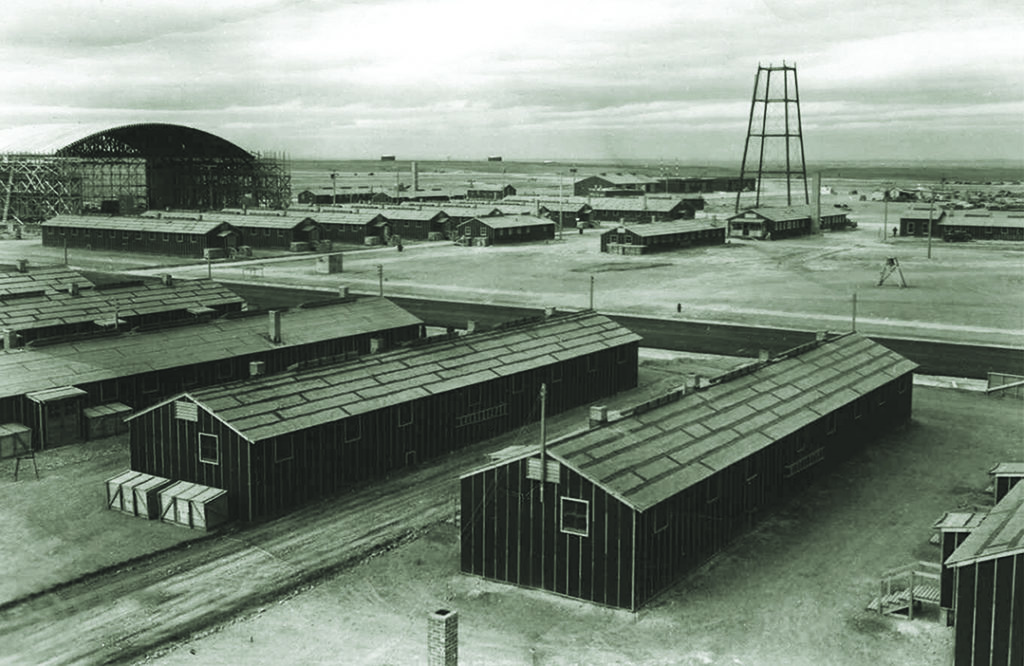

Construction of all four bases began immediately. By late October, Cut Bank, like its sister airfields, had three paved runways and wood-frame barracks, mess halls, administration buildings, and other structures intended to last just five to seven years. With the 352nd Air Base Squadron in place to manage operations, Cut Bank Army Airfield officially opened on November 11, 1942. The 260-some men of the 2nd Bombardment Group’s 429th Bomb Squadron arrived for training later that month.

Then, as now, the most prominent structure was the colossal 160-by-120-foot hangar—one of few remaining original buildings, along with the enlisted men’s recreation hall, the armament building, and a shed for storing flammable liquids. On the short walk from the terminal, I notice that the paint job on the hangar’s asbestos-sided western façade, completed eight years ago, has taken a beating from the incessant gusts that plague this part of Montana. “The wind vibrates the nails right out of this stuff,” Nollkamper’s voice echoes as we step inside the cavernous building. The scent of oil overwhelms me as I admire how tiny the eight private Cessnas and Pipers parked along the sides seem in a space designed to barely hold a pair of B-17s. When the original mechanical doors—replaced by smaller sliders in 1962—folded open to welcome a Flying Fortress, the sound thundered all the way into town.

Despite the noise, the community was proud to host the base. Cut Bank Pioneer Press articles of the day tell of soldiers joining locals for holiday meals, ring-necked pheasant hunts, and 50-mile Sunday drives to Glacier National Park. The Blackfeet tribe adopted dozens of airmen in elaborate cultural celebrations. Even when temperatures dropped well below zero, off-duty airmen would load into canvas-backed army trucks for the bumpy ride into town to catch a high school basketball game or patronize the USO in the basement of the yellow stucco Masonic temple that still stands on Main Street.

Cut Bankers donated phonographs, furniture, games, and books to fill the enlisted men’s recreation hall. A dozen years ago, not long after the airport had rehabilitated the 40-by-132-foot building from a postwar stint as a rabbit-breeding facility, a tornado-strength microburst blew the western two-thirds of it across the nearby highway. The airport used Army Corps of Engineers blueprints to reconstruct it to original specifications. Nollkamper credits the rabbit waste with preserving the blue lines of a wartime-era shuffleboard court on the slick cement floor. Grubby past aside, it’s not a stretch to imagine romances budding beneath streamer-adorned rafters there—at least 20 visiting airmen married local women.

Local hospitality prompted the 429th to pen a letter of superlative gratitude to the town in December 1942. “Perhaps someday, in the not-too-distant future,” the anonymous author wrote in the Pioneer Press, “you will read your paper and say, ‘I remember that squadron—they were part of us for a while.’”

Indeed, these airmen made an indelible mark on the war. The 429th, together with the other three squadrons that trained here—the 385th Bombardment Group’s 550th Bomb Squadron, the 390th’s 569th Bomb Squadron, and the 401st’s 613th Bomb Squadron—would fly more than 1,200 missions in North Africa and Europe, including Elmer Ruschman and crew’s D-Day run. Collectively, the squadrons dropped 71,000 tons of bombs, shot down more than 1,000 enemy aircraft, and earned six presidential unit citations. The most widely publicized veteran was probably Skippy, the pit bull a Cut Bank high schooler gifted to a 429th pilot. Equipped with a homemade oxygen mask, the dog flew more than 200 hours over Tunisia and Sicily.

The snow has retreated, so Nollkamper and I explore the crumbling concrete hardstands where squadrons tethered their B-17s each night. We cruise the primary southwest-bound runway in his Honda, stopping where the modern pavement ends at just over a mile. I poke through the bunchgrass and consider whether the reddish gravel beneath could be debris from the army’s original runway, which was 50 feet wider and extended another 2,800 feet. The heavy B-17s needed plenty of room when they took off to rendezvous with sister squadrons and pummel the prairie with sand-filled practice bombs. Nollkamper still gets calls from farmers who find old shells in their fields. He hopes to add some to the museum when funding allows for a move to the armament building where the B-17s’ machine guns were stored each night. The expanding collection includes the blue-and-yellow Link Trainer flight simulator in which dozens of pilots who trained at the airfield polished their flying skills. For years after the base closed, Cut Bank High School aeronautics students, including Nollkamper, used the trainer to get a feel for the thrill of flight.

Like today’s snow flurries, the army withdrew from Cut Bank and the other satellite airfields rather suddenly in October 1943, and without explanation. In 1948, the land was turned over to the city and Glacier County, which repurposed a few buildings and parceled out the rest to locals for home and commercial construction projects.

I end my day in town, walking the cliffs above Cut Bank Creek as the rosy hues of sunset disappear behind the jagged outline of the Rockies. On the drive out, I scan the rows of houses in vain for evidence of the scrapped army buildings. The physical relics, like the memory of the airfield’s wartime past, have blended discretely into Cut Bank’s quiet streets.