In recent years, the phrase “Jim Crow” has seen much use. Ire at a congressional rollback of federal Voting Rights Act protections, at state efforts to restrict access to polling places, and at police violence against unarmed African-Americans has caused official and unofficial voices to declare that Jim Crow is back—and never actually departed.

Were most Americans to guess, they might suppose incorrectly that the term came about when a fellow named Crow signed onto an obscure 19th-century lawsuit. Others might know that at one time “Jim Crow” was a common insult aimed at blacks; fewer, that Jim Crow was a figure well-known in rowdy, racialized stage shows that were among the foundations of American popular entertainment. But hardly anyone knows that the “Jim Crow” lately mentioned—President Barack Obama used the term in his January 10, 2017, farewell address—originated as a folkloric figure made a household word by a gifted white actor celebrated for his blackface performances in the mid-1800s. In the 1890s, when Southern states began to impose segregation, that practice was branded “Jim Crow.” How a stage character became a ubiquitous shorthand for legal subjugation by race is a story with a subversive genealogy that goes to the heart of the American identity.

New Orleans shoemaker Homer Adolph Plessy boarded a passenger car of the East Louisiana Railroad on Tuesday, June 7, 1892. As Plessy knew, the coach was reserved for white customers. At the corner of Press and Royal Streets, police placed the 28-year-old African-American under arrest, an outcome the activist and accomplices had engineered as the opening gambit in a legal challenge. Plessy and company wanted to contest a Louisiana law requiring rail companies to seat blacks and whites in different cars.

A descendant of Creoles who had fled Haiti decades earlier, Plessy described himself as “seven-eighths Caucasian and one-eighth African.” Plessy and many others of black and mixed-race descent living in cosmopolitan New Orleans were determined to challenge the Louisiana rail car law, enacted in 1890, an early ripple in a tide of restrictive legislation Southern states passed after Reconstruction that came to be known colloquially as “Jim Crow.”

John Howard Ferguson, the judge assigned to Plessy’s arrest, ruled that “equal, but separate” accommodations on public transportation did not violate the shoemaker’s constitutional rights. Plessy appealed Ferguson’s ruling. His case rose through the courts, ending in 1896 with one of the U.S. Supreme Court’s most consequential decisions. Plessy v. Ferguson gave legal cover to Jim Crow laws.

The purpose of Louisiana’s “Jim Crow car” law was “to separate the Negroes from the whites in public conveyances for the gratification and recognition of the sentiment of white superiority and white supremacy of right and power,” wrote Plessy’s attorney, Albion Tourgée, a Union Army veteran and radical. Begun on railroads, a herald of the industrialization disrupting the established social order, this racial ostracism soon “extended to churches and schools, to housing and jobs, to eating and drinking,” historian C. Vann Woodward wrote in his 1955 book, The Strange Career of Jim Crow. “Whether by law or by custom, that ostracism extended to virtually all forms of public transportation, to sports and recreations, to hospitals, orphanages, prisons and asylums, and ultimately to funeral homes, morgues, and cemeteries.”

Jim Crow measures in effect constituted “an interlocking system of economic institutions, social practices and customs, political power, law, and ideology, all of which function both as means and ends in one group’s efforts to keep another (or others) in their place,” historian John Cell wrote.

The performer who made Jim Crow Jim Crow was a Caucasian. Born in 1808, Thomas Dartmouth Rice, a furniture maker’s son, grew up in lower Manhattan near the East River docks. In his racially mixed working-class neighborhood, young Rice likely would have attended traveling shows that were staged in the saloons which in that era often doubled as theaters in New York and around the country.

Since the mid-1700s, in Britain as well as in American colonies soon to become states, rambunctious productions often had featured white actors donning wigs and smearing burnt cork on their faces. These African-American characters often were comic.

Separately, African-Americans, enslaved and free, told among themselves folktales in which animal characters tricked their way to spoils or victory, disrupting the balance of power—witty allegories on human existence. In these tales, roosters chased foxes, goats terrorized lions, Brer Rabbit taunted Wolf, and crows stood up to bullying bullfrogs. Blacks on islands across the Caribbean and along the Carolina coast sang a ditty, “Jump Jim Crow.”

Little is known of Thomas Rice’s youth except that he preferred treading the boards to making cabinets. In 1827, the 19-year-old made his show business debut with a circus in Albany, New York. Tall and thin, an able mimic, songwriter, and comedian, the youth adopted the stage name T.D. Rice, working theatrical circuits in the Mississippi and Ohio valleys and around the Gulf Coast.

Convention has it that the germ of the Jim Crow character took root after Rice observed a crippled black man dancing and singing somewhere in Ohio or Kentucky. Rice decided to imitate the fellow in blackface and, in that guise, call himself “Jim Crow.” William T. Lhamon, author of the 2003 book Jump Jim Crow, argues that no matter where exactly Rice may have happened onto his inspiration, “Jim Crow” by then had become a fixture in corners of American culture, especially among blacks.

Around 1830, Rice appears to have fleshed out the character’s persona, as well as the song “Jump Jim Crow.” To go with his impudent air, “Jim Crow” sported ragged and patched clothing, suggesting the garb a runaway slave might wear, and adopted a signature crooked posture. Scholar Sean Murray suggests this pose was commenting on the risk of crippling injuries that workers in factories and other industrialized settings faced in the United States, where census takers in 1830 began counting “cripples” as a category.

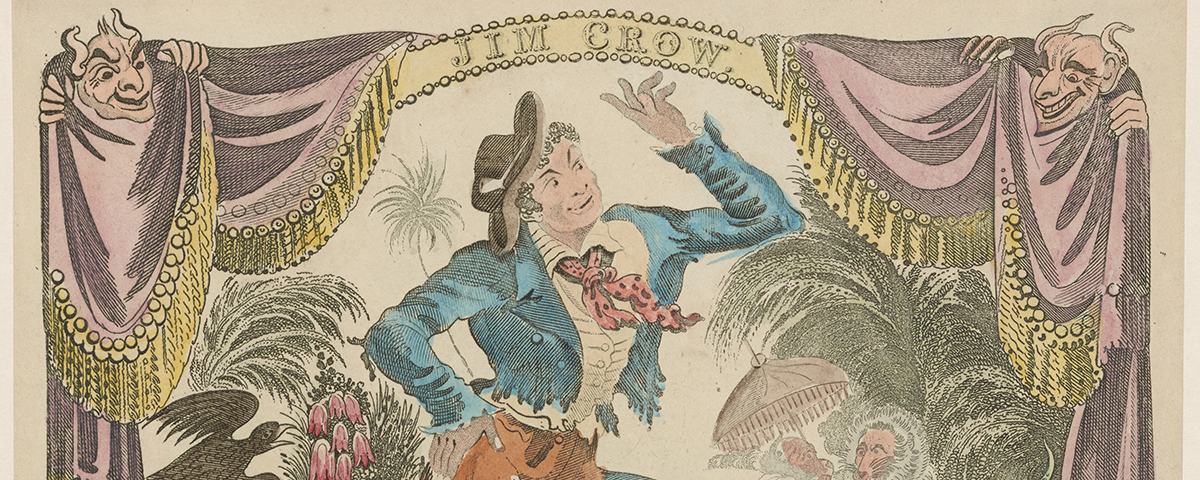

Rice unveiled his new character and verses he had written at the Bowery Theatre in New York City on November 12, 1832. Performing “Jump Jim Crow,” Rice boasted of trickster Jim’s misadventures, bewitching his audience. “Wheel about and turn about and do jus’ so,” Rice sang as he danced. “Every time I wheel about I jump Jim Crow.” Called back for encores, Rice transfixed crowds six nights running.

Jim Crow embodied the strivings and frustrations of laborers of all races and circumstances who were wise to their oppressive masters. This was something new. Rice’s character, Lhamon argues, was the first to refer “to a very real cross-racial energy and recalcitrant alliance between blacks and lower-class whites.” Studying early American plays, theatrical productions, and song lyrics, Lhamon came upon Rice’s scripts and realized he had stumbled upon examples of some of the young republic’s earliest overtly working-class theater. Jim Crow penetratingly mocks the status quo, such as in “Jump Jim Crow,” when he makes fun of southerners’ vehemence in denouncing a tariff on imports—one of the South’s key antebellum gripes—and demanding nullification:

De great Nullification,

And fuss in de South,

Is now before Congress,

To be tried by word ob mouth.

Dey hab had no blows yet,

And I hope dey nebber will,

For its berry cruel in bredren,

One anoders blood to spill

An if de blacks should get free,

I guess dey’ll fee some bigger,

An I shall consider it,

A bold stroke for de n——.

I’m for freedom

An for Union altogether,

Aldough I’m a black man,

De white is call’d my broder.

In another song, Jim Crow boldly labels whites devils and threatens to repay insults with violence.

What stuf it is in dem,

To make de Debbil black

I’ll prove dat he is white

In de twinkling of a crack

For you see loved brodder,

As true as he has a tail,

It is his berry wickedness

What makes him turn pale.

An I caution all white dandies,

Not to come my way,

For if dey insult me

Dey’ll in de gutter lay

By no means the first white performer to appear in blackface, Rice stood out because his material deeply engaged the mixed-race, working-class audiences made up of people, Lhamon observes, who Rice would have come to know in his travels in Appalachia, the Gulf Coast, and the South, where blacks and whites mingled in railyards, in shipyards, and on canals.

Soon Rice was writing sketches starring Jim Crow; in none, Lhamon notes, does the character surrender his autonomy—and Jim Crow always outwits his white superiors. The rascally character, an American archetype, charmed onlookers of all ages. The audience at a performance Rice gave in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the 1830s, may have included a young musical prodigy bound for success as a songwriter. Biographers of Stephen Foster, born in 1826, say he was 10 when he began performing his own version of “Jump Jim Crow.”

Of Rice as Crow in 1836, a New York critic wrote, “in language he is obscure, ridiculous, yet cunning; in antics he is frisky—in grimace frightful, and in changing positions or shifting sides he is inexhaustible, endless, marvelous [sic], wonderful.” His act grew popular enough for him to take it across the Atlantic. Between 1836 and 1845, Rice performed in London, Dublin, and Paris. The song-and-dance man excited fans. “The most sober citizens began to wheel about, and turn about, and jump Jim Crow,” a critic wrote in the New York Tribune in 1855. “It seemed as though the entire population had been bitten by a tarantula; in the parlor, the kitchen, in the shop and the street, Jim Crow monopolized attention. It must have been a species of insanity, though of a gentle and pleasing kind.”

Imitators trod Rice’s pioneering path, individually and in groups. In the 1840s, “minstrel shows” became the rage. Overacting in ludicrous “Negro dialect,” these troupes of white performers in blackface sang and danced in sketches that often revolved around life among an imaginary plantation’s slaves. All over the country but particularly in cities, where plantation culture was a novelty, minstrel shows persisted for decades. Having grown up and become a bookkeeper—a career path he was trying to escape—Stephen Foster broke into show business when the Christy Minstrels and kindred outfits hollered and hoofed his compositions “Camptown Races,” “De Ol’ Folks at Home,” and “Oh, Susanna!”

Jim Crow entered the larger culture. An 1839 English novel, The History of Jim Crow, chronicles a young black man’s escape from bondage and his efforts to reunite with his family in Richmond, Virginia. Around 1850, a Glasgow, Scotland, publisher put out a children’s book, The Humourous Adventure of Jump Jim Crow. And early in her 1852 blockbuster Uncle Tom’s Cabin, abolitionist author Harriet Beecher Stowe has Mr. Shelby, a slave trader, tossing raisins at a young slave child he summons, addressing the youngster as “Jim Crow.” Those blander mainstream Jims, Lhamon argues, reflected not Rice’s subversive persona but condescending stereotypes.

In 1840, Thomas Rice began to experience mystifying bouts of paralysis. However, the show had to go on, and Rice kept working, creating and landing new roles. He recast William Shakespeare’s Othello, a murderous drama of seduction and betrayal, as an irreverent musical with himself in the lead, a role he would recapitulate. Otello debuted in Philadelphia in 1844, returning to that stage three years later in tandem with the first stage production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was enjoying a second life as a play. In 1854, a New York City run of Uncle Tom’s Cabin cast Rice, in counterpoint to his career-making brazen Jim Crow, as benevolent martyr Uncle Tom. That show featured Stephen Foster’s plaint, “Old Kentucky Home.” Scholars interpret this and similar material by minstrel show songwriters as an expression of the feeling of dislocation gripping Americans of all classes at the time. People were anxious about the effects of rapid industrialization and the threat posed by immigrants, especially from famine-ridden Ireland.

According to this reading, plantation melodies distilled a comforting nostalgia for a vanishing, highly romanticized agrarian past.

Now one of America’s leading songwriters, Foster had traveled south only once on a Mississippi riverboat and never lived in the region. Still, influenced deeply by Rice, he projected mixed messages in his songs, portraying black characters as cartoons yet also making them human. After his 1850 marriage to Jane McDowell, from a staunchly abolitionist family, Foster quit minstrelsy, dropping buffoonish caricature and instead treating black and white characters with equal sympathy, even giving some lyrics an abolitionist spin.

Industrialization allowed some Americans to afford a parlor and a piano. Amateur musicians wanted simple, tuneful songs to play and sing, and by the mid-1850s Foster was turning out melodies aimed at young middle-class women playing pianos in genteel parlors, as opposed to raucous, tricky tunes suitable for being shouted out by dangerously hilarious actors in rough-and-tumble theaters, the way T.D. Rice had gotten his start. Foster’s brother claimed his sibling met Rice in 1845 and later sold the performer two songs. Rice’s descendants maintained that Rice declined Foster’s material as too stridently antislavery to perform universally, but did encourage his fan to keep writing.

Rice died in 1860, at 53, and was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. His will stated that his occupation was to be recorded as “comedian.” Rice’s compellingly transgressive cross-racial persona, with its slyly veiled but unmistakable challenge to power, outlived him, not only in performances by inheritors but as the ironic label given to what became deadly subjugation with a global reach. From 1890 through the 1960s, Jim Crow kept a white knee on the necks of southern blacks. In 1948, white South Africans, inspired by that example, imposed their own system of segregation, apartheid. South Africa’s take on Jim Crow lasted until 1994.

Rice’s tradition came to include immigrant show folk and artists who also exploited blackface—and the cultural wealth of the African-American experience. “Imitating perceived blackness is arguably the central metaphor for what it means to be American,” Lhamon wrote, “even to be a citizen of that wider Atlantic world that suffers still from having installed, defended, and opposed its peculiar history of slavery.”

Generations of American performers devised variations on T.D. Rice’s provocative racial impersonation—to name a few, Irish-American minstrel impresario Dan Emmett; Lithuanian-born singer and actor Al Jolson, a rabbi’s son; and Brooklyn natives Ira and George Gershwin, songwriters whose immigrant parents were Russian Jews. In time, performers like Elvis Presley and Eminem would drop the mask and sing in their own white working-class skin, delivering entertainment percolating with interracial influence just as disruptive as Jim Crow more than a century earlier.