As dawn broke on the last day of 1910, things were looking up for Arch Hoxsey. The early bird pilot had broken the world altitude record by soaring to 11,474 feet on December 26 and won more than $6,000 in prize money at an international air meet in Los Angeles. On New Year’s Day 1911 he was to ride on the first-ever aviation float in the Rose Bowl Parade. At their Pasadena home, Hoxsey’s mother fixed her son breakfast and kissed him goodbye. She had originally agreed to go aloft with him that day but at the last moment decided against it.

In breaking the altitude record Hoxsey noted that he had experienced “the most terrifying cold I ever felt.” On December 31 he would attempt to best his own record and then planned to head on to San Francisco for another international aviation meet starting January 3.

The 26-year-old aviator had pursued a flying career since he was 18, when he went to work as a mechanic for the Wright brothers. In 1910 he became a Wright team pilot. Aviation historian Arch Whitehouse referred to him as “one of the most personable airmen of his time—the dandy of the barnstorming circuits.”

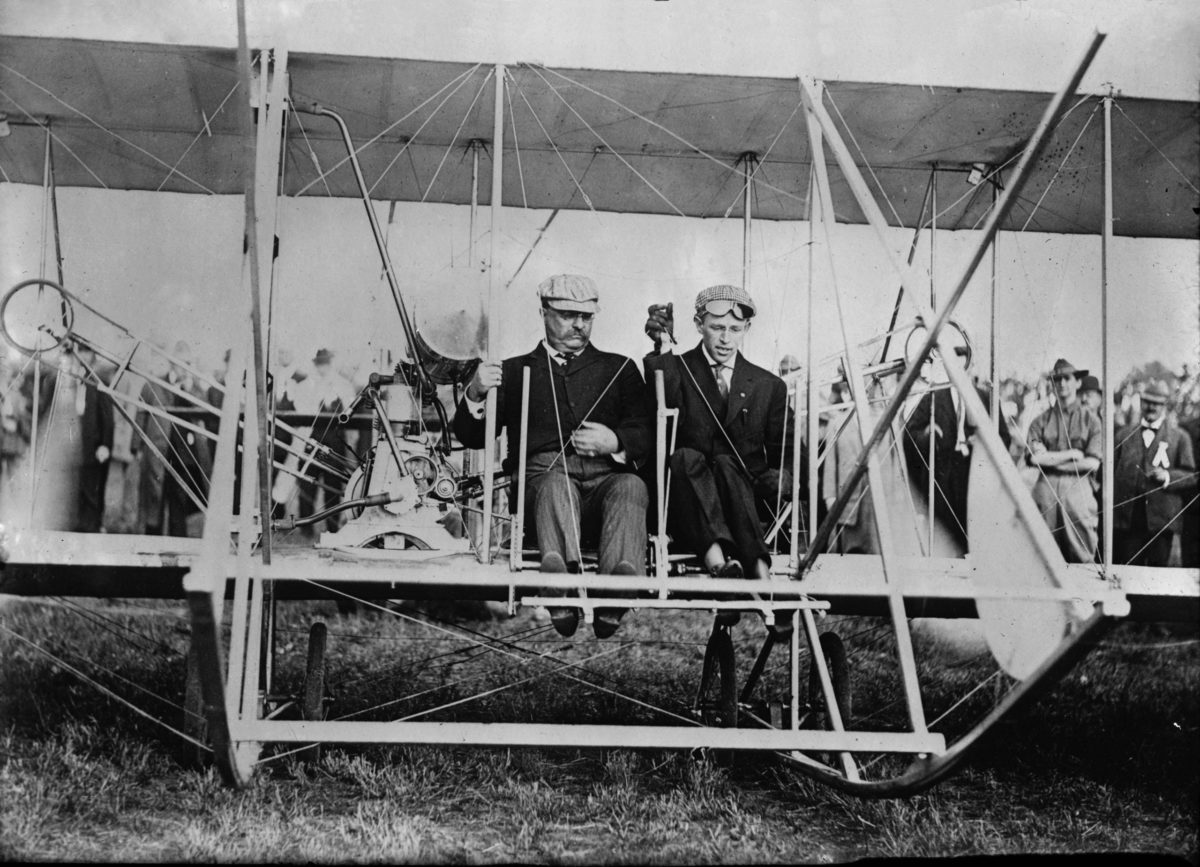

Hoxsey had gained international prominence 12 weeks earlier on October 11 by convincing ex-President Theodore Roosevelt to fly with him at Kinloch Field outside St. Louis. In an impromptu meeting between Hoxsey and Roosevelt, the aviator said, “Colonel, I’d like to have you go up with me.” He mentioned to TR that they celebrated the same birthday, October 27. “After I told him [that] he smiled,” Hoxsey said. “As soon as I saw his smile, I knew I had him.” Roosevelt took off his frock coat and climbed into Hoxsey’s Wright Model AB.

They landed after a few passes over the airfield with some dips and climbs. Newspapers reported that Roosevelt, “smiling his most expansive smile,” vigorously shook Hoxsey’s hand. “It was great!” the president enthused. “It was the finest experience I ever had.” TR told the aviator that he “wished he could stay up with you for an hour” but his schedule prevented it.

After leaving Kinloch, Roosevelt went to Clayton, Mo., where he enthusiastically told an assembled crowd “of his trip in the airship.” This was followed by a stop at the St. Louis state fairgrounds, where he spoke to several thousand school children. “I know you children would cheerfully play hooky for a week to go up in an aeroplane,” said TR, “so you won’t blame me for being a little late.” Later that evening he insisted that Missouri Governor Herbert Hadley invite Hoxsey to the governor’s mansion for their dinner. There Roosevelt told Hoxsey: “That was the bulliest experience I ever had. I envy you, your professional conquest of space.”

Roosevelt had been involved with aeronautics from its very start. In 1902 famed Brazilian balloonist Alberto Santos-Dumont visited the White House to meet the president, who suggested he be taken aloft. Newspapers across the country generally condemned the idea. The Evening Journal in Wilmington, Del., for example, opined that TR’s “life and limbs…belong to the nation quite as much as to him individually” and that “It would be….an unnecessary jeopardy….for him to go sailing around the clouds.”

Roosevelt stayed on the ground during his presidency. He approved the assignment of Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge to participate in early aeronautical experiments with Alexander Graham Bell and Glenn Curtiss. During Roosevelt’s presidency, Selfridge became the first person and first military pilot to die in an airplane crash. In April 1910 TR witnessed his first flight demonstration in Paris.

When Hoxsey took off in his Wright biplane on December 31, 1910, it would be his last flight. He was up an hour and a half soaring over California’s 5,710-foot snowcapped Mt. Wilson. He had descended in spirals to within 800 feet of the landing strip when he seemed to drop out of the sky. “A sigh or gasp, not loud, but of tremendous volume, arose from the grandstand,” The Cairo Bulletin reported. Fellow Wright teammate Walter Brookins “uttered but one word, ‘God!’…and he fell into the roadway.” Curtiss team member Charles Willard “likewise collapsed.” Hoxsey’s body was impaled on parts of the wrecked Wright airplane.

The following day Rose Bowl officials paraded the aviation float “draped and with a vacant seat” in his memory. The Wright brothers gave Mrs. Hoxsey a $10,000 annuity. Roosevelt, paying tribute to his friend, said, “I am more grieved than I can say over the tragedy….Hoxsey was a man unafraid….Such men as he are the ones who accomplish things in the sphere of science and of all activity.” Three months later TR stopped by Mrs. Hoxsey’s home in Pasadena during a campaign tour to personally express his condolences.

What actually happened to Arch Hoxsey? Most of his fellow aviators, including Curtiss and Wright team manager Roy Knabenshue, attributed Hoxsey’s crash to his hurried descent from high altitude, causing what they called “mountain sickness” or “ethereal asphyxia.” Early aviator Calbraith Rodgers described it as a sensation that “creeps irresistibly upon the senses of the aviator, lulling him into a dreamy unconsciousness.”

Today we know no such condition exists, and it seems likely Hoxsey was adversely affected by winds during his descent. An October 1928 Popular Aviation article reported: “After he was in the air the wind began to increase rapidly in violence….Evidently the wind whipped [Hoxsey’s plane] out of control when it entered the disturbed air near the ground.”

Roosevelt and Hoxsey had been friends a mere 12 weeks. TR would live to see his youngest son, Quentin, an acclaimed U.S. Army Air Service pilot, shot down and killed in action on the Western Front in July 1918. That September the Army named the eastern airfield at Mineola, N.Y., Roosevelt Field in Quentin’s honor. Teddy Roosevelt followed his son west in January 1919—he was 60.

This article originally appeared in the March 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!