At its outset, the Aerial Experiment Association might have seemed an unlikely venture. Launched in 1907 at the summer home of 60-year-old Alexander Graham Bell, this small group of youthful engineers and mechanics was originally organized to implement Bell’s theories of manned flight in multicellular tetrahedral kites. Funded by Bell’s wife Mabel (affectionately known as the AEA’s “little mother”), the enterprise quickly blossomed into a truly collaborative effort focused on powered aircraft. In just 18 months they would build four airplanes, conduct the first public flying exhibition in America and make the maiden flight in Canada.

Though Bell is best remembered today for his research in hearing and speech—which led to his invention in 1876 of the first practical telephone—flying had long fascinated the Scottish-born inventor. In 1896 he photographed Samuel Pierpont Langley’s 14-foot steam-powered drone in flight, and the Wright brothers’ first flight in 1903 electrified him. Like the Wrights, Bell at first tested aeronautical ideas with kites. He experimented with donut-shaped and trapezoidal models, eventually constructing a structure he judged large enough to lift a man.

In 1907, when U.S. Army Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge consulted Bell about military applications for aircraft, the inventor asked his old friend President Theodore Roosevelt to assign the young serviceman to work directly with him on his kites. Bell also invited John A.D. “Jack” McCurdy and Frederick W. “Casey” Baldwin, recent graduates from the University of Toronto who were on his staff at Baddeck, to help.

Bell’s team still lacked one essential player. The aging inventor envisioned a powered kite, and to realize his dream he considered motorcycle racer and engine expert Glenn Curtiss “invaluable—and indeed necessary.” Curtiss, who hailed from upstate New York, had already met the Bells. Alexander called him “the greatest motor expert in the country.” Now he startled the motorcycle man by offering him a chance to fly.

Unlike Selfridge, McCurdy and Baldwin, 29-year-old Curtiss was a married man running a successful business; it was much harder for him to justify suddenly running off to Bell’s home in Nova Scotia to work on flying machines. On the other hand, given Bell’s reputation, it was a bit like having Albert Einstein or Stephen Hawking ask you to help with their work. How could you turn them down? After some hesitation Curtiss agreed to join the group, which was officially founded in October 1907. Selfridge, who would serve as the AEA’s secretary, succinctly stated the newly founded association’s mission: “To get into the air.”

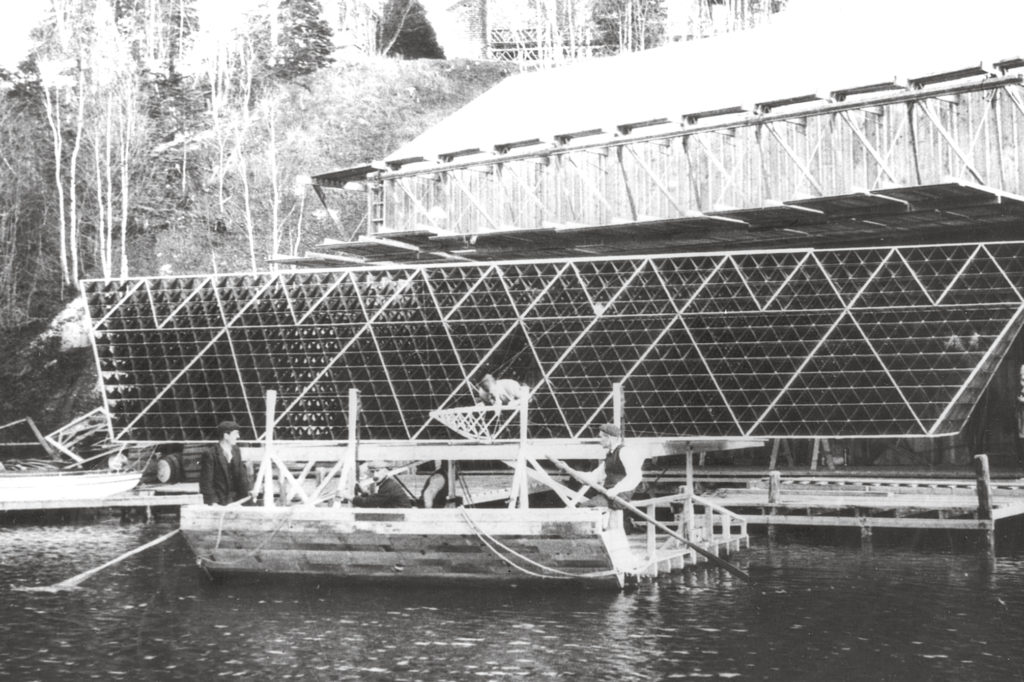

Bell’s kite was all of 60 feet across, incorporating 3,400 tetrahedral cells. Curtiss and the others instantly recognized that while it might fly, it would never be practical. The four younger men politely but firmly insisted that once they tried out the kite, they would be able to turn their hand to airplanes—or aerodromes, in their own terminology. Each man would take his turn as lead designer, with the others supporting him, and each aircraft would build on lessons learned from its predecessors. To put it into perspective, the four new planes would come close to doubling the number built in North America thus far. Unfailingly generous, Bell agreed to their terms.

On December 6, Selfridge crawled inside the framework of Bell’s giant kite, dubbed Cygnet, and prepared to make the first unpowered test flight. A steamboat towed the kite out onto Bras d’Or Lake near Cape Breton Island. As the towline tightened, Selfridge suddenly be – came airborne. Though the young lieutenant was doubtless tense— after all, he was learning his new job second by second—he and the rest of the team must have been thrilled as Cygnet, covered with red silk, sailed through the sky nearly 200 feet above the water’s surface. After seven minutes in the air, however, the kite plunged into the frigid lake and was destroyed.

The team quickly retrieved the lieutenant, who apparently was not much the worse for wear, then packed up the leftover silk and headed for Curtiss’ home in Hammondsport, N.Y. So much for the kite. “Bell’s Boys” were already dreaming up an airplane. Though Bell was disappointed, he continued supporting the group.

They started their New York experiments with a Chanute-type hang glider. That February locals watched them as they ran down a mountain slope, soared a few yards into the air, then slid through the snow. Meanwhile the team was also constructing an engine-powered aircraft, despite the fact that none of them had ever actually seen such a thing aside from in a photo. Even so, they finished building their airplane within eight weeks of putting pencil to paper.

Red Wing, whose wings were covered with silk left over from Bell’s kite, was Selfridge’s project—a pusher biplane with opposing dihedrals, equipped with skids for taking off on ice. Selfridge, however, had been called away on Army business by the time it was ready for testing, and Curtiss confronted the others with an uncomfortable truth: The ice wasn’t going to last much longer. So on March 12, 1908, they manhandled the aircraft aboard a coal barge and headed for frozen Lake Keuka. They gingerly slid Red Wing over the gunwales on planks onto the narrow beach. After Curtiss checked his engine one last time, they were ready for their first flight attempt.

With Selfridge away, the others had drawn straws to determine who would man the machine, and Baldwin won the honor. He clambered through the bamboo framework to straddle the pilot’s bench. They started its engine and hung onto the plane while Baldwin revved up the motor. When they let go, he lurched forward, skittering across the ice “like a scared rabbit,” as Curtiss later wrote. Red Wing flew straight and true, however, rising roughly 20 feet above the lake and settling back onto the ice 319 feet after it took off. That first flight was a spectacular success, especially considering that the machine was utterly untested, and that Baldwin had had no flying lessons.

Five days later they were back at the lake, with Baldwin wearing his lucky green tie in honor of Saint Patrick. He lifted off in Red Wing and flew 40 yards, then…horror. One wing dipped almost straight down, catching the ice with its tip. The aircraft started cartwheeling, with its youthful pilot still inside the birdcage framework.

Men raced forward, to be stopped by barked orders from Curtiss, who shouted that they would break the ice and send both machine and man to the bottom. The rescuers then cautiously advanced to where Baldwin was extricating himself from the wreckage. He escaped with only scrapes and bruises, but Red Wing had been destroyed.

The problem quickly became obvious even to the self-taught aeronauts. Baldwin could pitch Red Wing’s nose up or down with an elevator up front, and turn left or right with a rudder in back. But he had no means of controlling the roll of the wingtips; Selfridge had counted on high inherent stability in his design. It was evident to all that they needed far more control in the air. Frustrating though this was, it fit right into the AEA’s plans—to create a series of planes, each building on what the designers had learned from its predecessors.

Now it was Casey Baldwin’s turn to serve as lead designer, and he already had some changes in mind. In May the team wheeled out its second aircraft. They’d salvaged the engine and tail from their previous effort, but since they were finally out of red silk, this one was dubbed White Wing. Fabric covered its nose, affording the pilot at least the psychological impression of shielding. It also had wheels (they experimented with three or four). More significant, White Wing marked what was possibly the first American use of ailerons. Triangular panels at all four wingtips provided the roll control that Red Wing had lacked.

Thanks to the AEA team’s trials, some of which attracted crowds, Hammondsport locals were becoming a techno-savvy bunch. That spring they were impressed to find a celebrity in their midst: Alexander Graham Bell had arrived to watch the next round of experiments. He stayed with the Curtisses, whose constantly ringing telephone reportedly disturbed the inventor’s sleep.

The flight tests now moved outside the village, to the Pleas ant Valley Wine Company’s grounds. Bell was on hand to see both Baldwin and Selfridge take White Wing aloft. On May 21 Curtiss celebrated his 30th birthday with a flight, first pulling Baldwin’s fabric shield off the plane’s nose (he insisted on a full range of vision). Taking off with ease, he flew more than 1,000 feet, bumping down just once. The other AEA men were impressed with his quick mastery of the controls; the New Yorker’s 15 years of racing bicycles and motorcycles were clearly paying off.

Next McCurdy, who was then on crutches from a fall off his Curtiss motorcycle, took White Wing up. He wrecked the machine on his first try. No one minded too much, though, since they believed they had learned enough from their work to get started on a new design.

This time Curtiss took the lead. Given his eighth-grade education, he sometimes felt a little awkward alongside his college-educated colleagues. But this was truly a team effort. For help he could count not only on the other AEA members, but also on Bell’s staff (which was used to experimenting) and his own staff (skilled at manufacturing). Nor did the list stop there. “Captain” Thomas Scott Baldwin (no relation to Casey), who manufactured airships in Hammondsport, sometimes resided with the Curtisses. In addition, other experimenters visited the town that summer in search of Curtiss engines, men working not only on airplanes and airships but also on helicopters and ornithopters. Everyone was looking over everybody else’s shoulder. Ideas percolated through the whole network, with the best ones bubbling to the top. It was a remarkably stimulating environment.

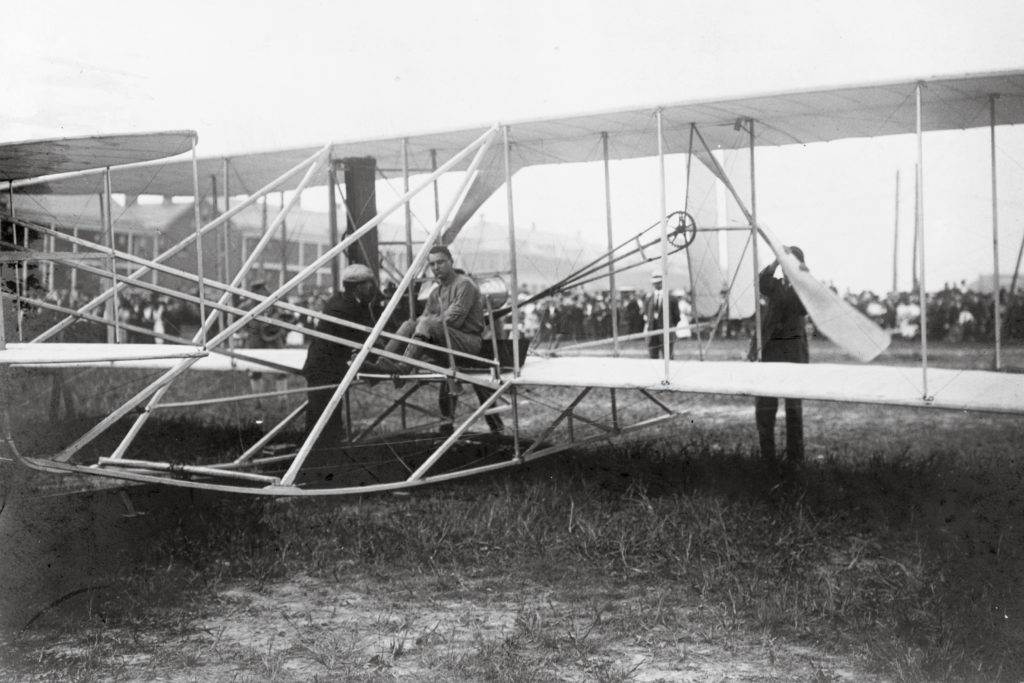

Curtiss’ project, christened June Bug by Bell, differed in looks only modestly from White Wing. Curtiss omitted the fabric shield and installed tricycle landing gear, with two rear wheels and a steerable nose wheel. He also stretched the airplane’s length and wingspan, and increased the square footage of the ailerons. As a result, the plane performed much better in flight tests, the first of which took place on June 21.

June Bug’s performance was so impressive that it prompted the team to wire the Aero Club in New York City, which was administering a competition for the Scientific American Cup, to be awarded for the first officially observed heavier-than-air flight of one kilometer with an unassisted takeoff and a safe landing. For a time the Aero Club officials stalled, hoping the Wright brothers would be the first to try. But Orville declined, pointing out how busy they were (Wilbur was in Europe at the time), and adding that it would require them to retrofit an airplane, since they preferred to use a catapult launch. Moreover, the Wrights thought of themselves primarily as scientists. Trophies, exhibitions, races and airshows were not high on their list of priorities.

So the Aero Club caved in, and Curtiss set a date for the AEA at – tempt: the Fourth of July. “Advertise it,” he told his teammates. “Invite everybody interested in flight. Draw a crowd to Hammondsport and prove to the world that we can really fly.” It would be America’s first exhibition flight.

A crowd is just what they got—more than 1,000 people, Selfridge figured, including a film crew. The morning of July 4 brought the threat of thunderstorms, and Curtiss didn’t like the air conditions. That meant everyone had to sit around and wait. Things started getting a little ugly around lunchtime, but then the winery invited everybody inside for a cold collation and impromptu tasting. The spectators decided they could wait a little longer.

By late afternoon, Curtiss was ready. He straddled June Bug’s seat wearing a tie but no jacket or cap. Warming up the engine, he rumbled forward, took off—and nearly came to grief. The tail had been set at the wrong angle. He shot off into a steep climb, and it took all his strength to control the plane and bring it back to earth. Eager hands helped wheel the aircraft back to the starting line and readjust the tail.

As Curtiss later described the scene to Bell, he was readying for his second takeoff when he spotted a photographer setting up just short of the kilometer mark. By his own admission, this provoked a sharp reaction in Curtiss, who had already suffered murmurings from the crowd because of the delays, then been embarrassed by his abortive takeoff. Now this annoying shutterbug was positioning himself for a photo of Curtiss failing to reach his mark.

This time the takeoff was perfect. With considerable satisfaction he sailed past the offending photographer and over the kilometer mark as the crowd roared in approval. To everyone’s surprise, Curtiss kept going. Just to spite the photographer, he hummed on down the valley in the bright blue sky. Winery workers snatched bottles from shelves and raced them out to the delirious crowd. June Bug would cover 5,085 feet at an average speed of 39 mph that day, setting new records for distance and time in the air during America’s first airshow.

Following June Bug’s successful demonstration, Bell asked Casey Baldwin to accompany him back to Cape Breton, where they worked on hydrofoils and the tetrahedral kite. McCurdy stayed on with Curtiss, working on his design for airplane number four. By that time, however, Curtiss and Selfridge were increasingly occupied with the U.S. Army’s plans for an embryonic air force.

Tom Baldwin had won a contract for the government’s first powered aircraft, a 100- foot airship bigger than anything that had ever flown in America. Curtiss was creating the liquid-cooled engine under subcontract. Baldwin borrowed a propeller design from Selfridge and adapted McCurdy’s biplane elevator design from the upcoming AEA plane. That August Baldwin and Curtiss constructed the dirigible at Fort Myer, Va., and spent two weeks conducting acceptance tests (it required two pilots). When the Signal Corps accepted the aircraft, designated SC-1, Bald win taught a group of officers to fly it, including Selfridge and future Air Corps chief Benjamin Foulois.

Selfridge stayed on in the Washington, D.C., area, since he was slated to serve as a member of the acceptance board for trials of the Wright Military Flyer in September. Orville Wright wasn’t happy about his involvement. The AEA was obviously a potential competitor, but the lieutenant was far and away the Army’s preeminent aviation expert.

On September 17, 1908, Orville took Selfridge up in the Military Flyer on a demonstration flight. After four circuits around Fort Myer, the right propeller split, resulting in a terrible crash. The Flyer was destroyed, and Orville seriously injured. Twenty-six-year-old Selfridge became the first man to be killed in an airplane crash.

The Army, the Wrights and the AEA were all staggered by the tragedy, but their work continued. Curtiss and McCurdy even rigged up floats on June Bug and rechristened it Loon. They made fruitless seaplane tests on Keuka Lake until McCurdy unwittingly damaged a float, sinking the aircraft at the dock. “Vaudeville performance by moonlight,” he wired Bell. “Submarine test most successful.”

None of this distracted McCurdy or Curtiss from completing Silver Dart, as McCurdy dubbed their next airplane. “She certainly is a beauty,” he wrote Mrs. Bell. Silver Dart had rubberized silk fabric, borrowed from Tom Baldwin’s work on the Signal Corps dirigible. It also featured large ailerons, a huge biplane elevator in the nose and—another first for American airplanes—a liquid-cooled engine. McCurdy boasted that the new plane had been built “like a watch.”

Following trials at Hammondsport, McCurdy and Curtiss dismantled Silver Dart for shipment to Baddeck. On February 23, 1909, they wheeled the biplane out onto the ice-covered Bras d’Or, in a scene reminiscent of Casey Baldwin’s first flight in their crude Red Wing 11 months earlier. A big crowd, mostly on skates, turned out to watch.

The dignified Dr. Bell jumped up in his sleigh as McCurdy and Silver Dart soared into the air for the first powered flight in Canada. But the flawless performance turned into near-tragedy when two little girls skated directly in front of McCurdy as he was landing. (Five years later Curtiss would still be complaining that the public, equating airplanes with balloons, did not realize how long it took a plane to stop.) Selfridge had designed the original Red Wing for maximum stability, but McCurdy had enlarged the control surfaces and deliberately sacrificed stability for maneuverability in Silver Dart. McCurdy calmly turned the aircraft aside, comfortably avoiding the girls and bringing it down for a gentle landing. The man who had wrecked White Wing and deep-sixed Loon, who could not be trusted to handle his motorcycle properly, was emerging as one of the finest pilots of the age.

That brilliant exhibition ignited the nation’s enthusiasm. Film footage of Silver Dart’s flight was seen in movie houses everywhere. “The whole country,” one Canadian paper reported, “had become flying-machine crazy.”

On March 31, 1909, the AEA was disbanded, with commercial rights to the designs and patents its members had initiated assigned to Curtiss. For the surviving AEA members and their associates, it had been a wild 18-month ride. They had built four increasingly sophisticated flying machines, along with a hang glider and a giant kite. They had heightened interest in aviation in the United States and Canada, and contributed to the birth of military air power. In the process, they had pioneered or advanced several key aeronautical innovations, including ailerons, tricycle landing gear and the liquid-cooled aero engine.

They had also buried a friend in Arlington National Cemetery. But as they did so, they did not forget Tom Selfridge’s vision for the AEA: “To get into the air.”

Bell, McCurdy and Casey Baldwin went on to build several more planes at Baddeck. McCurdy would take the lead in Canadian aviation production during World War II. Tom Baldwin, seeing the future in heavier-than-air flight, designed and commissioned his own fleet of exhibition aircraft.

Glenn Curtiss began building aircraft that were dramatically different from the AEA designs and the Wright machines. There is some evidence that his highly successful ideas originated from the AEA’s forgotten stepchild, the hang glider. Comparisons of the dimensions of contemporary aircraft suggest that he essentially added an engine and control surfaces to the hang glider when he developed his famed Curtiss pusher.

Curtiss, of course, became a colossus of American aviation, controlling perhaps three-quarters of the U.S. industry (plus more in Canada) by the end of World War I. He later turned to automotive work, but remained a director at his company, its Curtiss-Wright successor and several smaller firms until his death in 1930.

Casey Baldwin, who worked with Bell for years, left aviation behind in 1910. He served in the Nova Scotia legislature and died in 1948.

Alexander Graham Bell continued experimenting with kites and hydrofoils until his death in 1922, followed not long afterward by Mabel, the AEA’s financial angel.

John McCurdy flew extensively, including hops in a smaller powered version of Bell’s kite. He manufactured airplanes, headed up Curtiss Canada during World War I and served as a director of the parent Curtiss Company. McCurdy was also president of Curtiss-Reid until 1939, then served as Canada’s supervisor of purchasing and assistant director of aircraft production during World War II, and was made a member of the Order of the British Empire. He served as lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia from 1947 to 1952, dying in 1961.

As the last surviving member of the AEA, in 1959 McCurdy was flown to Baddeck, the group’s first home, for the golden anniversary of his flight in Silver Dart. Looking out the window while his airplane was on final approach that day, he saw a reproduction of Silver Dart flying below him—a fitting salute to an experiment begun more than 50 years earlier.

Did AEA Steal the Wright Stuff?

Kirk W. House, former director-curator of the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport, N.Y., has written extensively on aviation history. For further reading, he recommends his book Hell-Rider to King of the Air: Glenn Curtiss’s Life of Innovation; Glenn H. Curtiss: Aviation Pioneer, which House co-authored with Charles R. Mitchell; and Glenn Curtiss: Pioneer of Flight, by C.R. Roseberry. Note that you can see a flying reproduction of June Bug, as well as a Silver Dart replica on static display, at the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum (www.glennhcurtissmuseum.org).

Originally published in the July 2009 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.