On October 28, 1943, photographer Ansel Adams drove through the front gate of the Manzanar War Relocation Center. Set in the inhospitable desert of Owens Valley, California, Manzanar housed 10,000 American citizens of Japanese ancestry forcibly “evacuated” from the western states after Pearl Harbor and interned at Manzanar. Barbed-wire fences enclosed the 814-acre camp, and the rifles in the guard towers were pointing in.

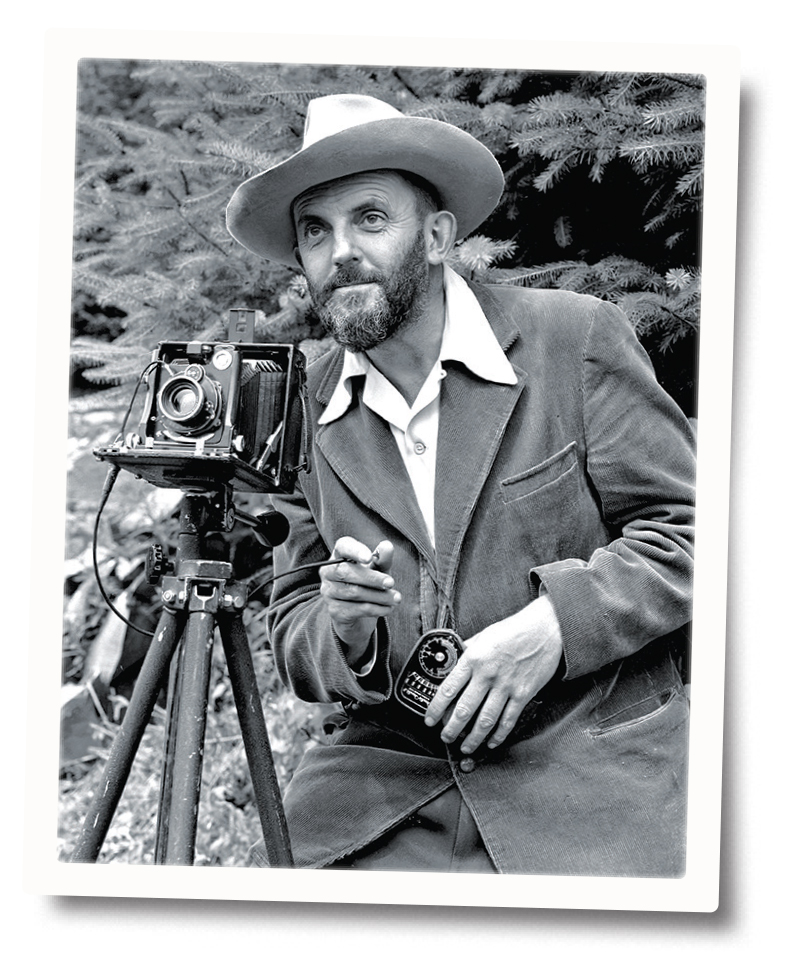

Over the next two months, Adams—known then as now for dramatic black and white landscape images—photographed the camp’s residents. In 1944, he published Born Free and Equal, a book about Manzanar. In its pages, Adams tacitly offered a perspective opposed to the anti-Japanese hysteria that had brought on the internment of loyal Americans. He celebrated the resiliency of the men, women, and children who endured this unwarranted hardship. Born Free and Equal, which never attained the stature of Adams’s many other books, demonstrated his great humanistic spirit and willingness to stand with the disenfranchised during a time of severe national stress.

Besides plunging THE UNITED STATES into World War II, Japan’s raid on Pearl Harbor crystallized hostility against the Japanese abroad and at home. As shocked West Coast residents were reading and hearing initial news reports about the sneak attack, California deputy sheriffs and agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation were already rounding up “Japanese suspected of subversive activities.”

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the Secretary of War to designate geographical areas from which “any or all persons may be excluded.” Suspect individuals would be “evacuated” to residential camps where they were to receive “food, shelter, and other accommodation”—and be kept under guard. The order, a mandate separate from those stipulating controls on foreign enemy aliens, who also were to be interned, specified no nationality, but there was no doubt about its target. Anti-Japanese hysteria had exploded, fed by rumors starring insurgents and saboteurs. Investigators testifying before the House Committee on Un-American Activities claimed that on the West Coast Japanese agents were strapping cameras to homing pigeons and setting the birds loose to fly over and document restricted areas. The Committee recommended that anyone in the United States of Japanese ancestry be moved 500 miles inland from the Pacific. (See “Days of Infamy”).

Three days after Roosevelt signed Order 9066, the FBI swept up 500 “enemy aliens” who, the Los Angeles Times reported, had “guns and ammunition, cameras, binoculars, flashlights, radios and alien flags.”

These “first triumphs of the war in the Pacific Coast States” were arrested in Los Angeles, Long Beach, and San Diego. Similar raids snared suspected saboteurs in Seattle and along the Oregon coast. The need for incarceration facilities spurred construction of “local detention centers” and “inland concentration camps.” In 1988, a congressional commission concluded that these arrests “were carried out without adequate security reasons and without any acts of espionage or sabotage documented by the Commission.”

Japanese victories in the Pacific theater heightened concern about a West Coast invasion. On February 24, 1942, the Los Angeles Times shocked readers with a story about a Japanese attack on oil fields at Ellwood, California, a coastal town 12 miles north of Santa Barbara. Japanese submarine I-17 lobbed 16 poorly aimed rounds into the facility, causing minimal damage. Witnesses swore that they had observed Japanese on the beach at Ellwood using signal lights to direct the barrage. Frightened Angelenos clamored for the removal of all people of Japanese descent, fearing they comprised a fifth column. “We must move the Japanese in this country into a concentration camp somewhere, some place, and do it damn quickly,” Representative Alfred J. Elliott (D-California), who represented Tulare in the San Joaquin Valley, told Congress.

On March 3, 1942, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, announced plans to relocate thousands of “enemy aliens.” As Java was falling to the Japanese, American officials were hastening to secure Pacific Coast states. The army listed three categories of people to be removed from exclusion zones: individuals suspected of espionage, immigrants born in Japan (issei), and second- or third-generation Japanese Americans whose parents or grandparents had been born in Japan (nisei). All parties in these categories were to relocate to one of 10 camps being readied in the American interior. Two weeks later General DeWitt announced the first “voluntary” relocation, set for March 23. The government was to ship 1,000 people of Japanese descent from Los Angeles to the Owens Valley, 224 miles northeast. DeWitt warned those affected to settle their affairs quickly. “I want it made unmistakably clear,” he told the Los Angeles Times, “that evacuation will be continued with or without cooperation.”

Archie Miyatake remembered internment unfolding quickly. “We heard rumors that our government was going to start evacuating everyone of Japanese ancestry,” he wrote later. Miyatake was 16, a student at East Los Angeles High School. The son of Toyo Miyatake, Manzanar’s unofficial photographer, he chronicled his experience in an edition of Born Free and Equal. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh no, how can they do that?’ I just couldn’t believe that they would do such a thing.”

By the end of March relocation was under way. The government forced affected citizens to sell their residences and businesses, pack, and move to relocation centers. To document the operation, the Wartime Relocation Authority, a civilian agency created to oversee the project, hired photographer Dorothea Lange, a star of the Depression-era Farm Security Administration photo unit. The wartime agency seemed to be expecting Lange’s work to complement favorable propaganda run in West Coast newspapers. Los Angeles Times stories went on about how smoothly the roundup was going, and how grateful those being displaced were for their government’s lenience: “The evacuees spoke highly of the government policy of keeping families together at Manzanar, explaining that such procedure [sic] meant the least possible interruption in their daily routine.” Coverage painted soldiers as kindly: “May I carry your bag, ma’am?” a Times staffer reported hearing an army lieutenant ask an older Japanese woman.

Lange was supposed to illustrate the benevolent treatment of happy internees, but the reality of the government action and her role in it horrified the photographer. “In contrast to her earlier work for a government social program to aid the poor, Lange now found herself photographing the execution of a government order to incarcerate American citizens based on their ancestry,” historian Jasmine Alinder writes. Lange rebelled, pointing her camera at scenes of dislocation and hardship: piles of luggage, “For Sale” signs in windows of abruptly closed stores, hand-lettered placards in shop windows announcing “I am an American”—disturbing parallels to increasingly familiar images from Europe of Nazi anti-Semitism.

Disheartened, the photographer left the WRA in July 1942. The agency locked away her photos until after the war. “I fear that intolerance and prejudice is constantly growing,” she wrote to Adams in November 1943. “We have a disease. It’s Jap-baiting and hatred. You have a job on your hands to do to make a dent in it—but I don’t know a more challenging nor more important one. I went through an experience I’ll never forget when I was working on it and learned a lot, even if I accomplished nothing.” In a 1961 interview Lange said the WRA had “impounded” and classified her negatives and prints from her days with the agency.

A San Francisco native, Ansel Adams, 41, found wartime frustrating. Though successful starting in the early 1920s with a balance of commercial, editorial, and personal work, he yearned to focus on artistic projects, particularly landscapes. In the 1930s, he had founded the f/64 group with kindred spirits Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston. He published books, had museum and gallery shows, and worked for corporate clients. World War II interrupted his burgeoning career. The market for his landscape photography dried up; buyers were not interested in beautiful pictures. He was too old to enlist or serve as a combat photographer. In a letter to Nancy Newhall, acting curator of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, he described his wartime contribution as “photographing Army convoys that visit Yosemite,” training military photographers at Fort Ord, California, and taking “Navy patients out for photographic sessions here in the valley….I have tried unsuccessfully to get into some work relating to the war effort…I certainly would like to be of use. So many things are at stake.”

In autumn 1943, Ralph Palmer Merritt, Manzanar’s new director, contacted Adams. The men had met as members of the Sierra Club. Merritt asked if Adams would be interested in photographing Manzanar residents. The idea, Adams wrote Nancy Newhall, was “to clarify the distinction of the loyal citizens of Japanese ancestry and the dis-loyal Japanese citizens and aliens (I might say Japanese-loyal aliens) that are stationed mostly in internment camps.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Both categories, noted Adams, faced intense hostility on the West Coast. The project was an opportunity to remind people that America was not at war with all people of Japanese descent—just those who supported Japan’s belligerence. Merritt’s putative project had no funding—Adams would not be working for the WRA. “I cannot pay you a cent,” Merritt told Adams. “But I can put you up and feed you.”

Adams also would have to get to and from Manzanar. Rationing regulations sharply curtailed civilian driving by limiting access to fuel and tires. Once his local rations board authorized Adams to obtain “ample fuel and adequate tires for the hundreds of miles of driving between Yosemite and Manzanar,” he arrived at the camp late in October 1943.

“My first impression of Manzanar was of a dry plain on which appeared a flat rectangular layout of shacks, ringed with towering mountains,” Adams wrote in an autobiography. “Under a low overhang of gray clouds, the row upon row of black tar shacks were only somewhat softened by occasional greenery.” Barbed wire fencing enclosed the camp, and a gatehouse garrisoned by armed guards emphasized its prison-like nature. First glances showed him much of what he had imagined when previsualizing the project, a process he had developed early in his career to enhance his literal and figurative focus no matter what the assignment.

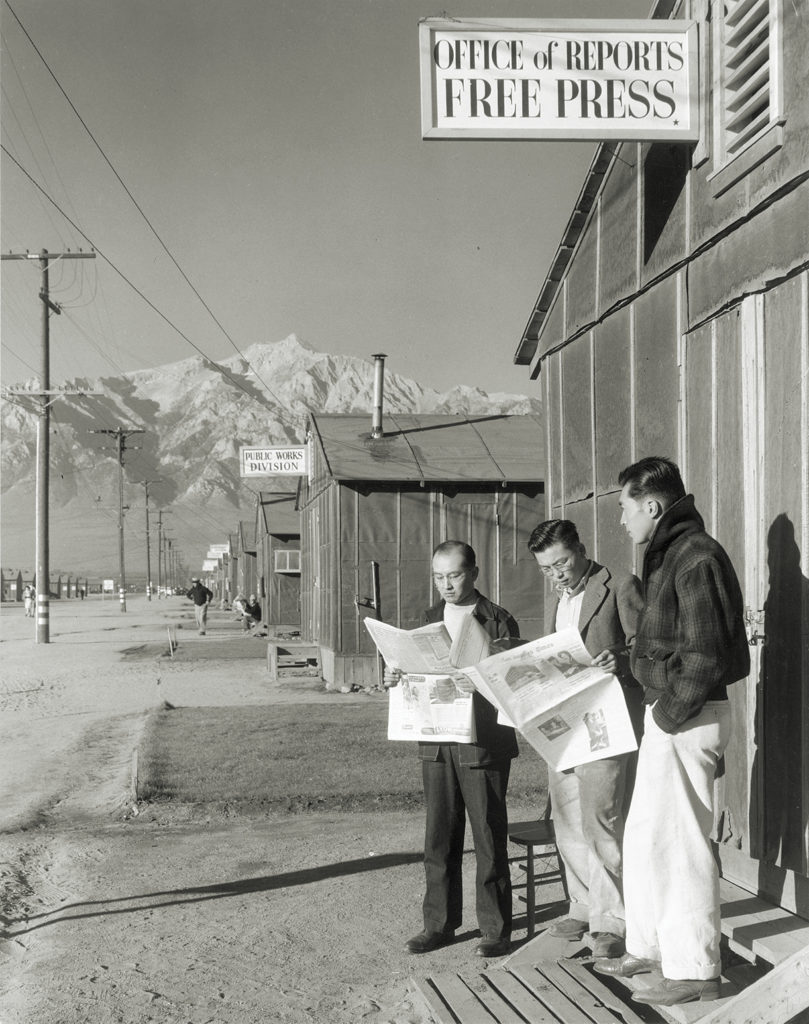

Meeting with Merritt, Adams requested to talk to camp representatives to ask permission for his undertaking. “The world famous photographer,” wrote the Manazanar Free Press, the camp newspaper, “expressed deep interest in doing an accurately representative pictorial of the evacuees, with particular emphasis on the loyalty of the niseis in the center.”

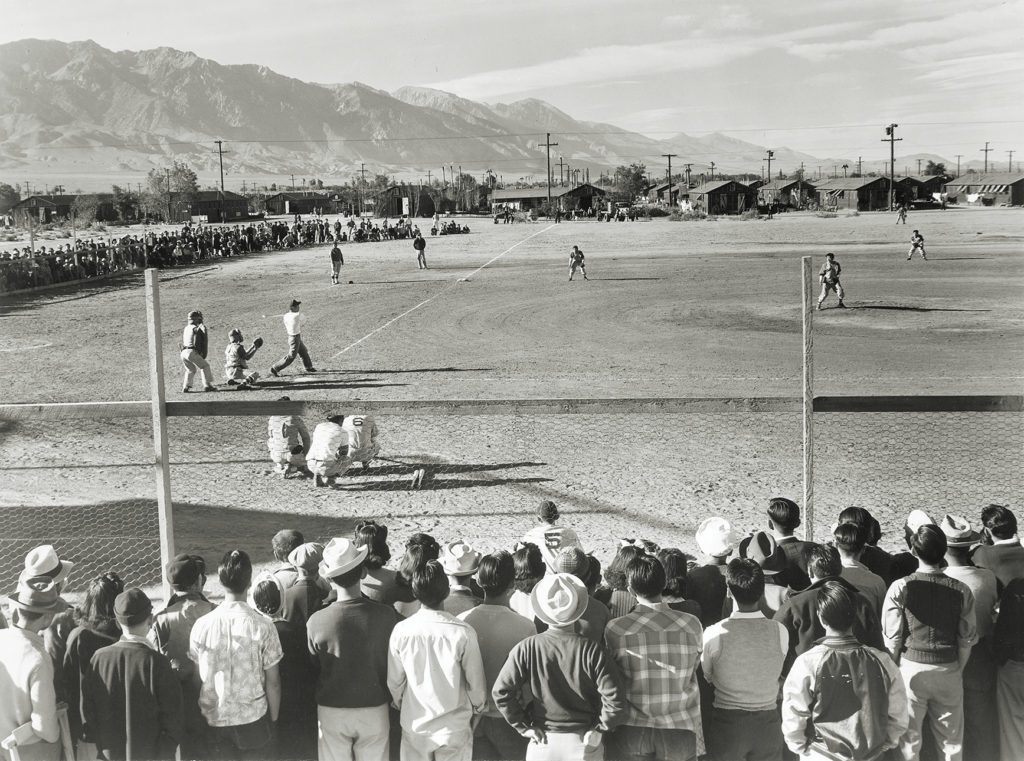

Warmly welcomed by internees, Adams unpacked his camera, a Graflex 4×5—so called because it took a single 4” by 5” sheet of film—and set to work. “He is the man you see wearing jeans and a windbreaker,” the Free Press wrote, “setting up his tripod and camera anywhere and anytime he finds a good subject to snap—be it at the hospital, nursery, mess hall, potato field or baseball field.” Adams was impressed with the center, continued the newspaper, and “his impression of the place far exceeded anything he expected.”

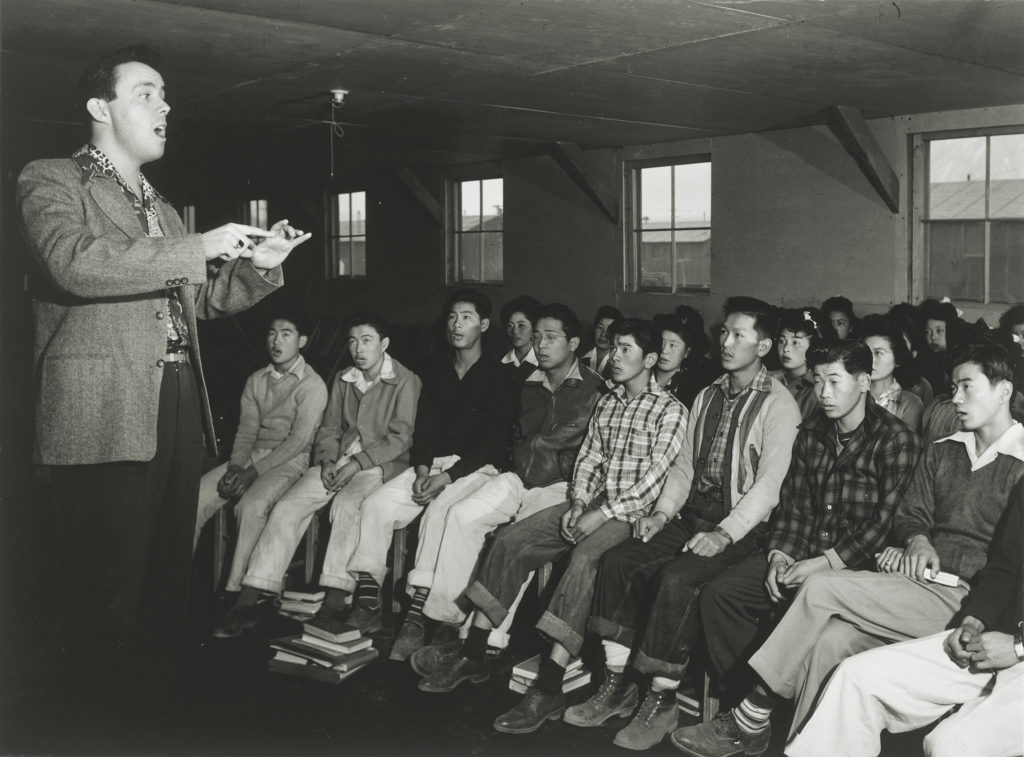

Adams quickly saw past the externals. Yes, those tarpaper shacks signaled “concentration camp,” but within them life was blooming. “The interiors of the shacks, most softened with flowers and the inimitable taste of the Japanese for simple decoration, revealed not only the family living spaces but all manner of small enterprises,” he wrote. “A printing press that issued the Manzanar Free Press, music and art studios, a library, several churches (Christian, Buddhist, and Shinto), a clinic-hospital, business offices, and so on.”

Adams had imagined possible photographic themes: unjust oppression by a government of its citizens, or possibly a propaganda piece illustrating the fine job the WRA was doing. He realized neither of these matched the complex reality of what he was seeing in the camp. The story was the people, and their resilience, a characteristic that allowed a despised and feared minority to adapt to unjust treatment and amid difficult circumstances get on with life. “With admirable strength of spirit, the Nisei rose above despondency and made a life for themselves, a unique macro-civilization under difficult conditions,” Adams wrote. “This was the mood and character I determined to apply to the project.” His subjects were so intent on making the best of their situation that Adams had difficulty documenting life as internees were living it; residents insisted on straightening up any setting he proposed to photograph.

After several sessions photographing at the camp, Ansel returned to Yosemite, processed his sheet film, and made 80 prints examining community life at Manzanar. The first exhibition of this work took place at the camp, where the prints were up for a week in January 1944. “Adams’s interest in the problem of minority racial groups,” wrote the Free Press, “and his desire to present an accurate story of the residents have produced results which depict Manzanar as it exists.” The work and the photographer’s commitment to it touched residents. “For a person like Ansel Adams to come to an internment camp to photograph camp life, where people are pretty bitter for being there, I thought, my gosh, this man is sympathetic to this situation, to the Japanese American people,” wrote Archie Miyatake. “I thought he was quite a man to be doing what he did at the time.”

Angry letters, some from parents of sons lost in the Pacific theater of operations, accused Adams of disloyalty.

After the Manzanar show, the photographs moved east. Nancy Newhall, of the Museum of Modern Art, agreed to exhibit the portfolio. On November 10, 1944, a 61-image series, Manzanar: Photographs by Ansel Adams of [the] Loyal Japanese-American Relocation Center, opened at the gallery and ran until Christmas Eve—but without enjoying pride of place. The museum, bowing to anti-Japanese hostility, barred use of the main exhibition space. The photographs were relegated to the museum’s auditorium galleries.

In a press release, Newhall endorsed documentary photography as a tool for healing racial divides: “With the coming of peace, photographers will undoubtedly play an increasingly significant role interpreting the problems of races and nations one to another all over the postwar world.” Adams, she wrote, had taken on that task and was avoiding “the formulas that have developed in documentary and reportage photography… has approached his subject with freshness and spontaneity.”

In time, Newhall was proven correct, but in the short term an America at war was not ready to reconcile with anyone. The exhibition received little media attention. The New York Times buried a short paragraph about the opening on page 17 of a Friday edition but ran no review.

As Adams was preparing for his MOMA show, Tom Maloney, publisher of the U.S. Camera magazine, offered to publish the Manzanar portfolio as a book. Debuting on the exhibition’s heels, Born Free and Equal developed the show’s theme; namely, that those behind the wire at Manzanar and other relocation camps were American citizens, legally indistinguishable from counterparts going about their lives. The book—“the story of loyal Japanese-Americans”—invoked the 14th Amendment’s declaration that all persons born or naturalized in the United States are citizens and shall not be deprived of “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” Adams also quoted Abraham Lincoln: “As a nation we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.’ We now practically read it ‘all men are created equal, except Negroes.’ When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read ‘all men are created equal, except Negroes and foreigners and Catholics.’ When it comes to this, I shall prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty.” His choice of Lincoln’s remarks suggest Adams regarded the internment of Japanese American citizens as a threat to democracy and a refutation of American ideals.

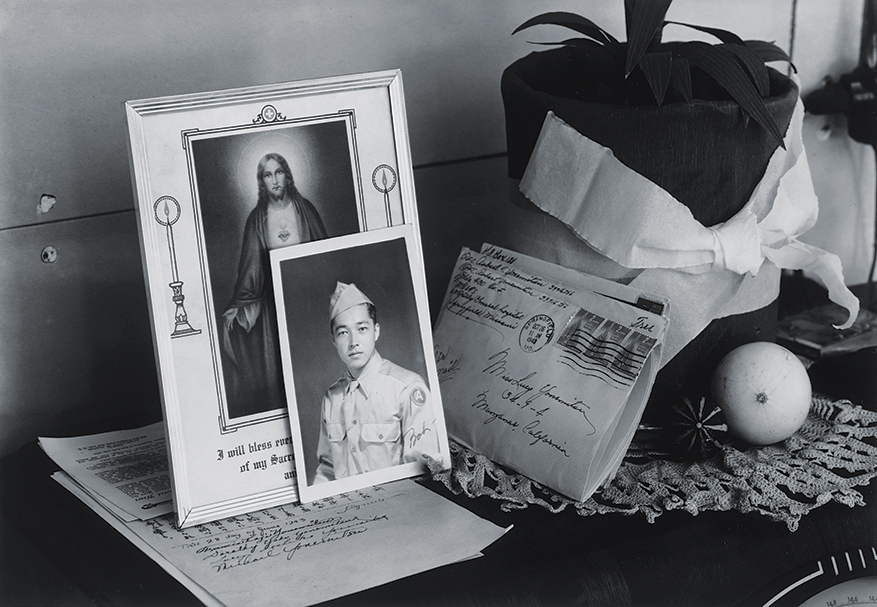

A turn of the page revealed Manzanar resident Yuri Yamazaki, grinning into the camera, her portrait cropped so that her face fills the frame. She could be any reader’s daughter. Adams captioned the image, “An American School Girl.” There followed a portrayal in words and pictures of a cross-section of American life—newspaper editors, farmers, soldiers, doctors and nurses, accountants and electricians. Subtract the guards and barbed wire, and the reader would find a community that, in nearly every way, was indistinguishable from any American town. To hate this population was as irrational as hating your own neighbors. “Americanism is a matter of mind and heart,” Adams wrote beneath one of his photographs.

Other than his opening references, Adams refrained from commenting directly on the relocation action, though he also quoted Manzanar director Ralph Merritt: “I have not said that the evacuation was JUST, but that it was JUSTIFIED.” Adams chose not to litigate. “Our problem now is not to justify those things which have occurred, but to establish a new and civilized rationale in regard to these citizens and loyal supporters of America,” he wrote. “To do this we must strive to understand the Japanese-Americans, not as an abstract group, but as individuals of fine mental, moral and civic capacities, in other words, people such as you and I…I want the reader to feel that he has been with me in Manzanar, has met some of the people, and has known the mood of the Center and its environment.”

Born Free and Equal was not a success. “It was poorly printed, publicized, and distributed, perhaps to be expected in wartime,” Adams wrote. Distribution was spotty; Ansel accused his publisher of printing too few copies. Even so, the book attracted admirers. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt praised it in her newspaper column: “In case you have not seen it, there is a publication by the United States Camera Publishing Corp. which is worth your looking through…it is one of the publications designed to temper one of our prejudices, and I think it does it very successfully.” Copies of the first edition regularly appear on offer online, some selling for hundreds, even thousands of dollars.

After the Supreme Court ruled detention of loyal Japanese American citizens illegal (In re Mitsuye Endo, December 18, 1944), the Pittsburgh Press published a full-page montage of Adams’s Manzanar photos and captions. “The recent order permitting the return of loyal Japanese-Americans to the West Coast brings to an end an unprecedented and poignant chapter in American History,” the afternoon daily declared in an editorial. “After many months of adjusting themselves to camp life, the Nisei must now try as best as they can to shuffle their way back into the stream of American life.”

Adams’s advocacy enraged many countrymen; reports circulated of bookstore customers buying copies of Born Free and Equal in order to burn them. Angry letters accused him of disloyalty, some sent by parents of sons lost in the Pacific theater of operations.

“They were bitter and incapable of making objective distinctions between the Nisei and Japanese nationals,” wrote Adams. “How can you adequately reply to a couple who lost their three sons in the Pacific War?”

Adams also drew fire from friendly quarters. Dorothea Lange derided his project as a whitewash, softening the horror of unjust incarceration with beautiful pictures. In a 1961 interview, Lange faulted Ansel for being ignorant when it came to social justice issues, although she admitted that Born Free and Equal had been a big step for him.

Modern historians tend to echo Lange’s critique, categorizing Ansel’s effort as little more than government propaganda and accusing him of doing far too little for the residents of Manzanar.

These anachronistic readings overlook two points. Although scholars applaud Lange’s adversarial stand against the government, her intransigence resulted in the censorship of her photography. Her work was not published until after the war ended. As an advocate for an oppressed minority, Lange was a failure. Adams’s images enjoyed a MOMA show, were printed in newspapers, and circulated in a book. It was Adams, not Lange, who shaped opinion and won sympathy for Manzanar’s residents.

Adams had little to gain and much to lose by inserting himself into the relocation debate. Wartime America remained virulently hostile toward the Japanese. It took great moral courage to wade into the hysteria and align with the supposed “enemies” interned at Manzanar, a choice that could have blighted the rest of his career. Knowing his unpopular stand threatened both reputation and livelihood, Ansel Adams still took the difficult path, striking a blow against injustice and irrational prejudice.

This article appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.