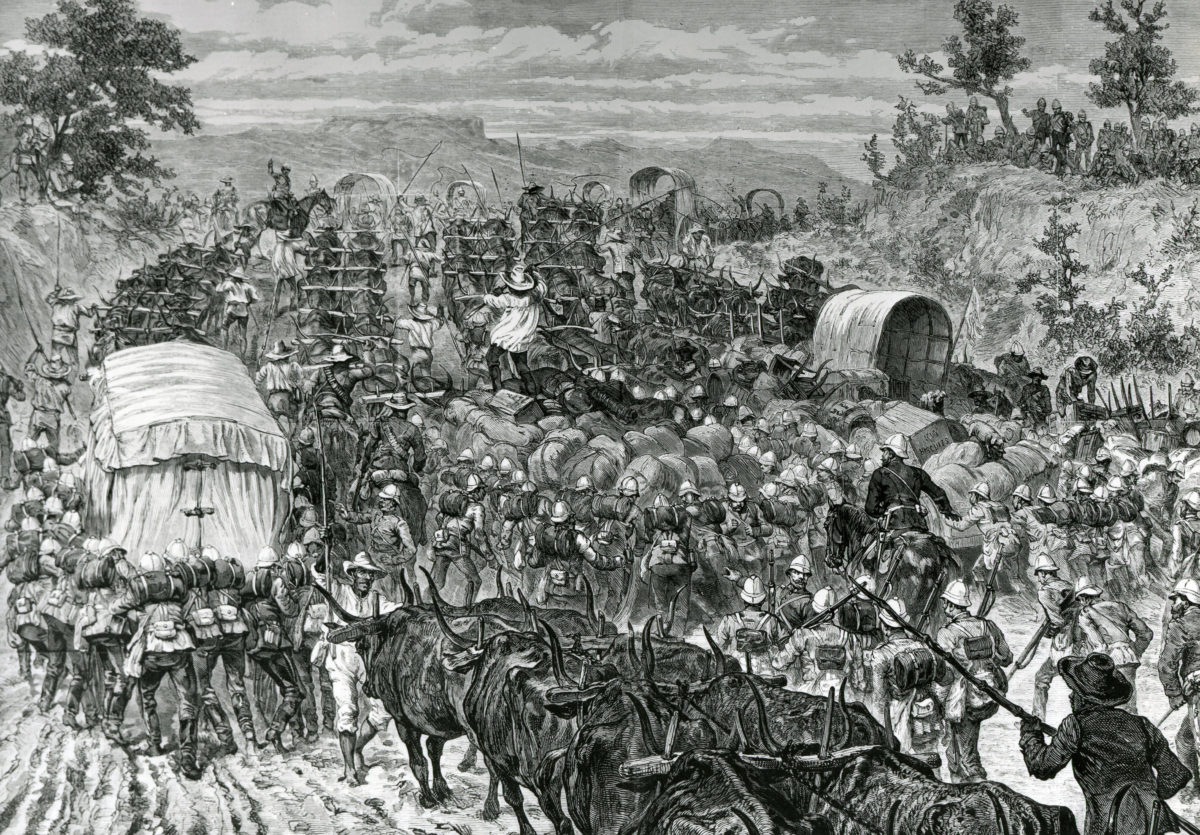

On Saturday, March 29, 1879, reveille sounded an hour before daylight at a British encampment in Khambula in northwest Zululand. For the men of Number 4 Column, part of a British invasion force in the Zulu kingdom, it had not been a peaceful night. The previous day, they had made a reconnaissance in force to the nearby enemy stronghold on Hlobane Mountain. What should have been a simple operation had turned into a nightmare. At a critical moment in the engagement, the abaQulusi and Khosa (prince) Mbelini kaMswati’s renegade Swazi defenders were joined by a Zulu impi (army) of some 20,000 warriors, and the British and Colonial forces under the command of Brevet Colonel Henry Evelyn Wood were routed. Almost 200 British, Colonial and loyal African troops had perished in the debacle.

Recommended for you

The British commander in chief, Lt. Gen. Frederic Augustus Thesiger, Earl of Chelmsford, had yet another reverse to add to the catalog of disasters that had beset him since he invaded Zululand on January 11–the worst being the slaughter of 1,200 of his troops at Isandlwana on January 21, which threw his entire invasion off-balance. He had hoped that the assault on Hlobane would serve as a diversion while he led a force to extricate Colonel Charles Knight Pearson’s column at Eshowe, on the coast, which had been under siege by Zulu forces since January 28. Sadly, the plans had gone awry.

As night fell on March 28, Wood’s badly mauled forces tended to their wounded and awaited the inevitable assault on their encampment on the ridge that was known locally as Ngaba ka Hawana (Hawana’s stronghold) but called Khambula by the British. Mounted Colonial volunteers under Brevet Lt. Col. Redvers Henry Buller searched the area in the vain hope of finding more survivors. Wood did not believe the Zulus would attack his position during the night, but he posted his sentries, and he could not rest. At least twice during the night he toured the outposts himself.

A thick mist shrouded the British fortifications as day broke on March 29. Wood soon discovered that two battalions of black levies—Wood’s Irregulars—had deserted. Only 58 men had remained loyal. Despite that mass desertion, the camp routine continued as usual. The wagon oxen were grazed, and a wood-cutting party went to gather firewood for the camp’s ovens and field bakery.

Commandant Pieter Johannes Raaff sought Wood’s permission to lead a 20-man party of his Transvaal Rangers to determine the present whereabouts of the Zulu force. Wood expressed his concern that the Rangers’ horses were too exhausted for such a reconnaissance, but he did agree to Raaff’s plan, realizing that he had to find out what the Zulus were up to.

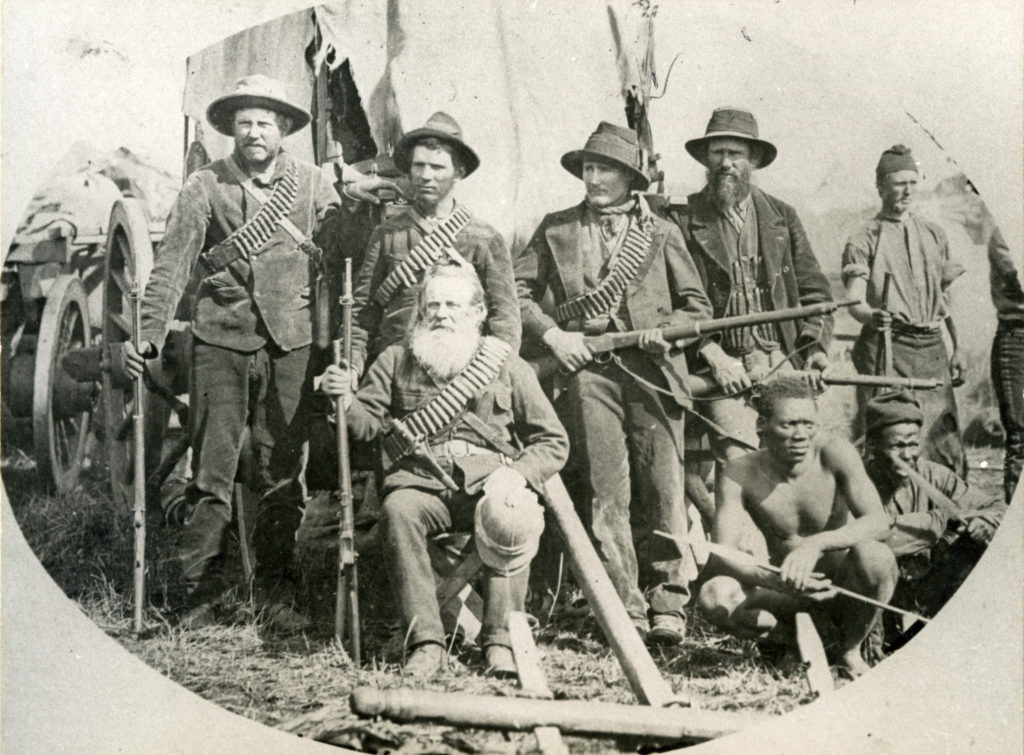

Shortly after Raaff set out, Wood received a delegation of men from the Burgher Force, a commando unit of Boers that had been called out by Petrus Lafrus Uys. They were the only Boers who had answered the British call to arms when war with the Zulus had broken out on January 11. Uys had died during the previous day’s action at Hlobane, and his men now told Wood that they wished to leave.

Wood knew that Boer Republicans had labeled Uys a traitor for assisting the British, whom they expected would ultimately submerge Boer independence within a Confederation of Southern Africa. Although Uys had had his own misgivings, he had said that it was a white man’s duty to be counted with those who were fighting the Zulus. (Uys’ father and brother had also been killed, fighting against the Zulu armies of King Dingane in 1838.) Given the critical role Uys had played in ensuring their shaky loyalty, Wood had no objection to the Boers’ departure. However, 10 men of the Burgher Force had hired wagons to the British, and those wagons now formed part of the defensive perimeter at Khambula. Perhaps to protect their own interests, those 10 chose to remain and fight.

The mist that had shrouded the countryside lifted at about 10 a.m. Raaff’s patrol was by then on the edge of the eZungwini plateau, some 12 miles from Khambula. Before him on banks of the White Mfolozi River, Raaff saw the Zulu impi, which had halted for a hasty meal. The Zulus had been living off the land since leaving oNdini (called Ulundi by the British) on March 24, intending to gorge themselves on Wood’s supplies once they had taken Khambula.

Raaff maintained his observation until the Zulu force began to move in the direction of Khambula. At 11 a.m., Raaff returned, bringing with him one of Prince Hamu kaNzibe’s men, who had been loyal to the British. The man had become separated from his own unit during the confusion of the previous day’s action. For his own safety, he had fallen in with the Zulu impi and had gleaned vital information regarding the proposed Zulu attack, which was scheduled to take place ‘at the white man’s dinner time. When Wood received that intelligence, he recalled the wood-cutting party and had the wagon oxen driven back inside the laager.

The Zulu strategy for the assault on Khambula had been conceived by King Cetshwayo kaMpande at oNdini, his great place–the Zulu seat of power. Wood’s column had been a thorn in the side of the local Zulu commanders in northwest KwaZulu (as they called their kingdom). Cetshwayo saw an assault on Khambula as an answer to their appeals to contain Wood’s raids into the surrounding countryside. The king entrusted the execution of his plan to Chief Mnyamana kaNgqengelele of the Buthelezi clan, his chief minister and adviser.

The forces mustered at oNdini were for the most part proud veterans of the great Zulu victory at Isandlwana, as well as the men who had suffered defeat at kwaJim (known to the British as Rorke’s Drift) on January 22. Cetshwayo’s orders were explicit: The impi would not assault the fortified position at Khambula. Instead, the Zulu force was to outflank the position and entice the British out from behind their defenses, then engage and destroy them in the open.

On the morning of March 29, Mnyamana relinquished command of the impi in favor of Chief Ntshingwayo kaMahole of the Khoza clan. Ntshingwayo was a most capable general–his deployment of the horns of the beast tactic at Isandlwana had proven that. Now he hoped for a second victory over the red soldiers.

Ntshingwayo’s adversary, however, was different from the commanders he had outmaneuvered at Isandlwana. Wood had chosen his own ground and prepared for any attack. On the western end of the ridge was an entrenched wagon laager, and on a small hillock to the east, a redoubt had been prepared. At the foot of the southwest face of the hillock was a cattle kraal, connected to the redoubt by a palisade. Four cannons had been positioned between the redoubt and the laager.

As a young midshipman in a Royal Navy landing brigade, Wood had been severely wounded in an attempted assault on the Grand Redan at Sevastopol during the Crimean War. That bitter baptism of fire changed Wood’s life, for he left the navy and joined the army, having acquired a taste for land warfare. The true architect of Wood’s defenses at Khambula, Major Charles Moysey of the Royal Engineers, was absent from the camp on March 29 on detached duty.

To defend the position, Wood had at his disposal the following forces: eight companies of his own regiment, the 90th (Perthshire Volunteers) Light Infantry; seven companies of the 1st Battalion, 13th (Prince Albert’s Own Somersetshire) Light Infantry; 110 artillerymen of the 11th Battery, 7th Brigade, Royal Artillery, serving the four 7-pounder cannons, supplemented by two mule guns manned by infantry volunteers; a sergeant and 10 sappers of the Corps of Royal Engineers; and the 58 officers and men of Wood’s Irregulars who had chosen to remain at Khambula. Colonel Buller, of the 60th (King’s Royal Rifle Corps) Rifles, commanded a mounted force composed of 99 officers and enlisted men of the 1st Squadron, Mounted Infantry; 165 officers and men of the Frontier Light Horse; 135 members of Raaff’s Transvaal Rangers; 91 troopers of Baker’s Horse; 40 members of the Kaffrarian Rifles; the 10 Boers of the Burgher Force; the 16 surviving members of Lt. Col. Frederick A. Weatherley’s Border Horse; and 74 men of the Natal Native Horse.

When the Zulu impi was sighted by the British defenders on March 29, its five columns appeared to be moving in a westerly direction. With the abaQulusi and Mbelini’s men, the mighty impi numbered some 25,000 men. About four miles southeast of Khambula, they halted. At 12:45 p.m., Wood ordered his bugler to sound the alarm. In less than a minute and a half, the tents were struck and the men deployed. In light of previous experience battling the Zulus, reserve ammunition boxes were opened and distributed.

At about the same time, the Zulus had formed into their traditional attack formation, the horns of the beast. The left horn, comprised of the battle-tested umCijo (also known as Khandempemvu) ibutho (regiment) as well as the uMbonambi and uNokhenke amabutho (regiments), moved south of the encampment. Meanwhile the center, or chest–made up of two amakhanda (regional corps), the uNdi (uThulwana, iNdlondlo and iNdluyengwe amabutho) and uNodwengu (uDududu, iMbube and isAngqu amabutho)–moved closer to the eastern end of the ridge. The right horn of the Zulu forces, consisting of another distinguished ibutho, the inGobamakhosi, moved north of Wood’s camp.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Wood was fearful that a group of the impi might break off and head toward the undefended border town of Utrecht. He also observed that the young warriors of the inGobamakhosi appeared to be eager for a fray, and he hoped to lure them into an engagement, thereby preventing them from attacking Utrecht. At 1:30 p.m., Wood ordered Buller and 100 of his mounted troops to ride out from the wagon laager and entice the inGobamakhosi toward the encampment. The troops rode out, halted and dismounted within range of the right horn. Buller then ordered them to fire a volley into the Zulu ranks. It had the desired effect–the young hotheads who had rushed forward at Isandlwana did so again. Buller’s men remounted and withdrew toward the laager, turning again and again to launch volleys at the pursuing Zulu warriors.

Lieutenant Colonel John Cecil Russell of the 12th (Prince of Wales’ Royal) Lancers, commanding the 1st Squadron, Mounted Infantry, came in peril of falling into Zulu hands as he struggled to mount his rearing horse. Troop Sergeant Major Learda, a baSotho of the Natal Native Horse, quickly perceived the situation and rallied a few men to snatch Russell from the jaws of certain death. Lieutenant Edward S. Browne of the Mounted Infantry rode up and steadied Russell’s skittish horse so that he could remount. Before Russell could put his feet in the stirrups or take the reins, however, his horse bolted again, carrying him across the oncoming line of inGobamakhosi until Browne caught up and led Russell to safety. Browne was subsequently awarded the only Victoria Cross of the battle. Learda received the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) for his action–if not for the prejudice of the Victorian army, he, too, might have been awarded the VC.

Meanwhile, the inGobamakhosi taunted the retreating British. Don’t run away, Johnnie, we want to speak to you, they jeered, boasting, We’re the boys from Isandlwana! The horsemen rode hell-for-leather back to the laager, except for the Natal Native Horse, which rode off to the west–perhaps the bitter lessons they had learned at Isandlwana had made them contemptuous of the British method of fighting. The remaining troopers made their way back into the laager under the cover of artillery fire. The right horn was within 300 yards of the north face of the wagon laager when a crashing volley emanated from the .45-caliber Martini-Henry rifles of Wood’s own regiment, the 90th Light Infantry. That deadly leaden hail ripped into the Zulus, decimating the leading ranks and shattering their advance. The surviving warriors threw themselves to the ground, hugging every bit of cover. With their position now untenable, the inGobamakhosi slowly withdrew to the northeast, the slope behind them littered with the bodies of their comrades.

On the rise behind the cannons, Wood saw one of his personal escort, Private Edmund Fowler, a mounted infantryman of the 90th, trying to shoot a Zulu inDuna (a local official who also served as a regimental commander in the Zulus’ army of citizen-soldiers). Fowler complained that his Swinburne-Henry carbine was shooting high of the mark. Wood threw the carbine to his shoulder and with his first shot brought down the inDuna and then two others. He then handed the weapon back to the bemused Fowler and instructed him to aim at the feet of his targets.

At 2:15 p.m., the Zulu center and left horn belatedly launched their attacks. The center moved against the southeast of the redoubt, while the left horn advanced into the dead ground below the south face of the laager. The uNokhenke stormed upward toward the redoubt, which was commanded by Major William Knox Leet of the 1st Battalion, 13th Light Infantry (1/13). The attackers were checked by the determined resistance of two companies of the 1/13 and one company of the 90th positioned there, together with the fire of the two emplaced mule guns, under the command of Lieutenant Frederick Nicholson, Royal Artillery.

The uNdi corps, which had been defeated at Rorke’s Drift, now rushed the cattle kraal being defended by Captain William Cox and some 150 men of the 1/13. Wave upon wave of Zulus rushed forward from their position in the former camp of Wood’s Irregulars. Cox and his men stoutly contested their front, meeting the warriors with the point of the bayonet, but their resistance was futile. Cox fell, shot through the leg; four of his men were killed and seven wounded. Wood sent a runner to order Cox to evacuate the position. Hard pressed, the soldiers retreated up the slope toward the ridge. Private William Grosvenor saw Colour Sergeant Arthur Fricker fall to the ground and rushed to his assistance. He helped the wounded noncommissioned officer to his feet, but Fricker was dazed. Rather than desert him, Grosvenor stood over the wounded man and fought against the Zulus until he finally slumped, mortally wounded, over Fricker–who would survive, thanks to the private’s selfless courage.

From the wagon laager, Private Albert Page, also of the 1/13, dashed across the bullet-swept open ground to rescue a wounded Swazi of Wood’s Irregulars and carry him back to safety. Page would receive the DCM for his actions. Grosvenor, who had given his life so that another might live, received no award, as there were no provisions at that time for gallantry decorations in the British army to be made posthumously.

Wood saw a man fall during the retreat, and he started down the slope to his aid. Wood’s staff officer, Captain Aubrey Maude, held him back, saying, Really, sir, it isn’t your place to pick up single men. Instead, Maude dashed forward himself, together with Lieutenant Francis Smith and 2nd Lt. Henry Lysons, to recover the soldier. Smith was severely wounded in the arm during the rescue.

Flushed with success, the uNokhenke took up position in the cattle kraal and began to fire at the wagon laager. Wood had his artillery commander, Major Edmund John Tremlett, reposition his four 7-pounders so that they could be used to maximum effect. In the redoubt, Lieutenant Nicholson fell mortally wounded, shot through the body, and command of the two guns there passed to acting Sergeant E. Quigley. Quigley’s great energy and zeal in the unfamiliar role of section commander would gain him a DCM.

The uMbonambi ibutho, comprised of some 1,500 men, formed up to the west of the cattle kraal, preparing to assault the wagon laager. To counter that threat, at about 3 p.m., Wood ordered two companies of the 90th, under the command of Brevet Major Robert Henry Hackett, a genial 43-year-old Irishman from King’s County, to move out from the wagon laager and disperse the Zulu formation. Under a heavy fire that was enfilading the southern front of the camp, Hackett, a pipe clenched in his teeth, led his 200 or so men with parade-ground discipline. The British charged with bayonets fixed, driving the uMbonambi from the ridge, then lined the ridge and poured volley after volley into the Zulu host. The uMbonambi gradually retired in the face of the more accurate fire. At the moment of his success, Hackett was shot in the head, the bullet entering one temple and exiting through the other. Twenty-one-year-old 2nd Lt. Arthur Bright assumed command of the detachment, only to be shot moments later, the bullet passing through both his legs.

The sortie had accomplished its objective–effectively destroying the impetus of the uMbonambi–but British casualties grew as troops of the 90th were caught in a deadly cross-fire from the cattle kraal and a small knoll to the southwest of the wagon laager, which the camp had used as a rubbish dump and was now occupied by the umCijo ibutho. Twenty-two-year-old Colour Sgt. Thomas McAllen, a promising young soldier, had already been shot once earlier in the engagement, but when he heard that his company was in the sortie, he hurriedly had his wound dressed and headed out to join his comrades–only to be shot in the head and killed. Wood could not allow his men to take such punishment and ordered them to retreat to the safety of the laager.

At 4:30 p.m., the Zulu right horn, the inGobamakhosi, charged forward from their cover toward the rear face of the redoubt, hoping to belay any criticism of their earlier impetuousness. On they came, only to be met by rifle and artillery fire, which cut channels into the ranks. Disheartened, the inGobamakhosi withdrew, while the redoubt’s defenders cheered their success.

Raaff then led a sally out of the wagon laager and engaged the Zulu riflemen ensconced in the rubbish heaps. Almost simultaneously, Captain Joseph Henry Laye’s men charged down from the redoubt and opened a deadly fire on the warriors in the cattle kraal. On the right, Captain John Miller Elgee Waddy led his company of the 1/13 out of the wagon laager, while two cannons were manhandled down to provide support for his troops. Wood was regaining the upper hand–Waddy’s men lined the crest that Hackett had occupied, and now it was their turn to drive back the Zulus. All around the camp the Zulus slowly withdrew. A few warriors stubbornly held their position in the cattle kraal, only to be dispatched by the bayonets of Laye’s men.

Wood then dealt his coup de grâce, unleashing Buller and his mounted force to pursue the fleeing Zulus. Captain Henry Cecil Dudgeon D’Arcy of the Frontier Light Horse, his mind still fresh with the horrors of Hlobane, exhorted, No quarter boys, and remember yesterday! The Natal Native Horse, which had been outside the fortifications harassing the Zulu flanks, rejoined the fold, eager to avenge the losses suffered at Isandlwana and Hlobane. Some Zulus turned and offered resistance, while others, exhausted, merely accepted their fate. Other Zulus killed themselves rather than suffer the indignity of falling into the hands of the British.

Commandant Friedrich Schermbrucker of the Kaffrarian Rifles recounted: I took the extreme right, Colonel Buller led the center and Colonel Russell with the mounted infantry took the left. For seven miles I chased two columns of the enemy. They fairly ran like bucks, but I was after them like the whirlwind and shooting incessantly into the thick column, which could not have been less than 5,000 strong. They were exhausted, and shooting them down would have taken too much time; so we took the assegais from the dead men, and rushed among the living ones, stabbing them right and left with fearful revenge for the misfortunes of the 28th inst. No quarter was given.

It was later calculated that Schermbrucker’s men had killed at least 300 Zulus. Buller’s party had accounted for 500 warriors, while Russell’s mounted infantry and the Natal Native Horse had killed at least 200 Zulus. It was not this slaughter that incensed the anti-war lobby in Britain, but a letter written by Private John Snook of the 1/13 on April 3 to a friend, which was subsequently published in The North Devon Herald on May 29, 1879. Snook wrote, On March 30th, about eight miles from camp, we found about 500 wounded, most of them mortally, and begging us for mercy’s sake not to kill them; but they got no chance after what they had done to our comrades at Isandlwana.

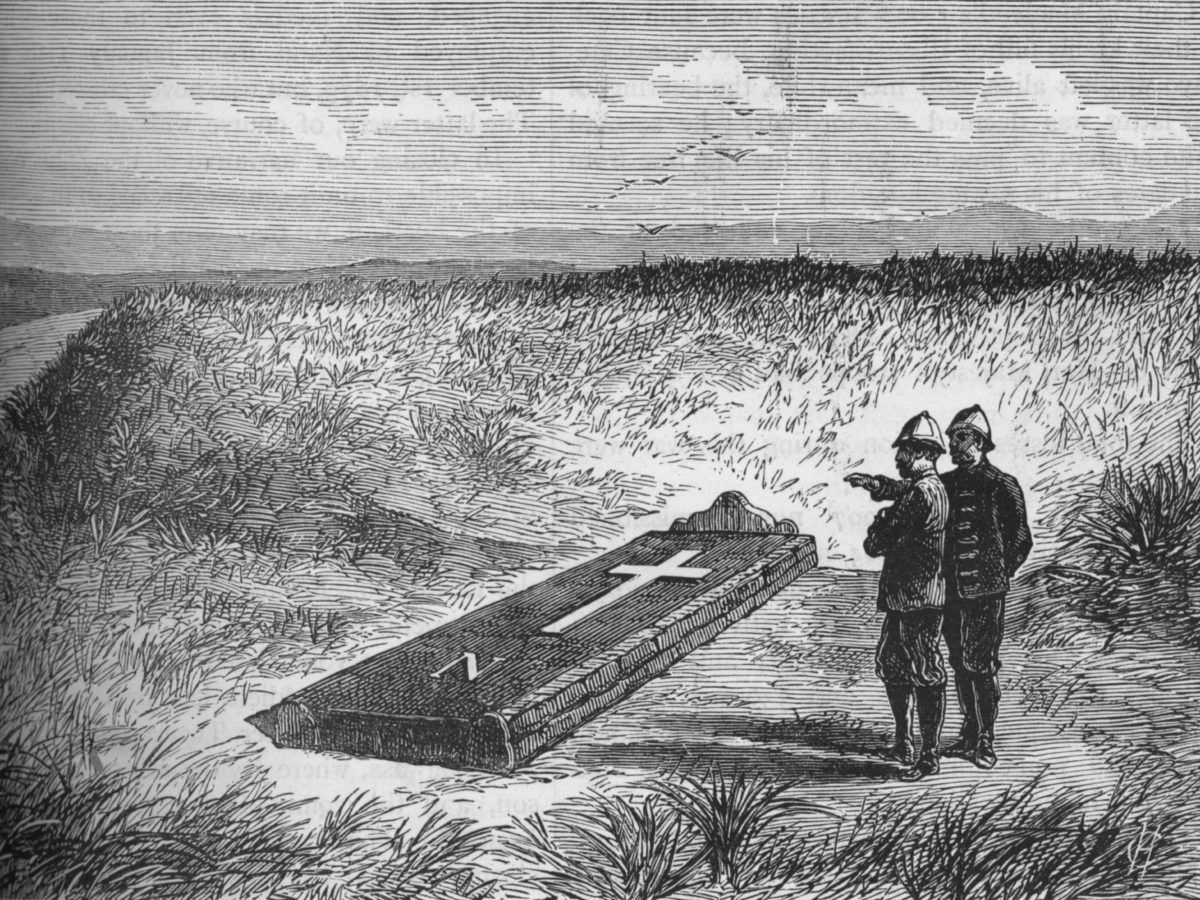

That comment outraged the Aborigines’ Protection Society at its Exeter Hall headquarters, and the organization formally expressed their disgust to the War Office. When Wood was compelled to issue a statement refuting Snook’s allegation, he said that all of his infantrymen had been employed on March 30 in the burial of Zulu bodies, of which there were no less than 785 in the immediate vicinity of the camp.

Figures on the number of Zulus who died in the assault and the subsequent savage pursuit vary, from a conservative estimate of at least 1,500 to a vastly exaggerated 6,000. Mournfully, Mnyamana reported to Cetshwayo that at least 3,000 men were missing from the ranks, including two of Mnyamana’s own sons. The king argued that his plans had not been followed, and he even threatened to execute the commander of the inGobamakhosi for his incompetence.

The Zulus were, however, praised by a British war correspondent who had witnessed the Zulu attack. But still on they came with the ferocity of tigers, never halting, never wavering, never flinching or hesitating for a moment, he wrote. Say what people may about its being animal ferocity rather than manly bravery, no soldiers in the world could have been more daring than were the Zulus that day.

Zulu courage notwithstanding, the British and Colonial forces had prevailed with few casualties. Only 16 men had been killed outright, and 16 more would die of their wounds, including young 2nd Lt. Arthur Bright, who bled to death in the hectic confines of the small hospital–the surgeons had dressed one wound, but in their haste had neglected to see that his other leg had also been injured. Fifty-three others had sustained wounds of varying degrees. As for poor blinded Robert Hackett, he was promoted to the rank of colonel and made an aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria, in order to make his remaining years more financially comfortable.

Never again would Cetshwayo’s army take to the field with such gusto, for the Battle of Khambula had turned the tide of the war in favor of the British. After March 29, Zulu courage would arise more from desperation than confidence. Chelmsford at last had his major victory, and Wood was the hero of the hour.

This article was written by John Young and originally published in the March 1998 issue of Military History. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Military History magazine today!