In March 1879, the Anglo-Zulu War was well into its third month, and two of the three British columns advancing into Zululand were stalled–one defeated at Isandlwana, the other surrounded and under siege at Eshowe. On March 20, Colonel Henry Evelyn Wood, commanding the only British force still capable of offensive action in Zululand, received a letter from the overall British commander, Lieutenant General Frederic Augustus Thesiger, the second Baron Chelmsford. Chelmsford wished to relieve the column at Eshowe, and he wanted Wood to demonstrate in his area to draw off some of the strength of a Zulu impi (army) that Chelmsford thought was gathering to attack Eshowe. That request gave Colonel Wood and his cavalry commander, Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Redvers Buller, an excuse to carry out an operation that they had been considering ever since they established their camp at Khambula. Wood’s goal was the destruction of the stronghold of the abaQulusi, a Nguni clan allied with the Zulus, located on a mountain 20 miles to the southeast, known as Hlobane (pronounced’shlo-BAH-nyeh’).

At the outset of the Anglo-Zulu War, the British governor of Cape Colony and high commissioner for native affairs in South Africa, Sir Henry Edward Bartle Frere, and his military commander, General Chelmsford, had formulated their plan for the invasion of Zululand. Chelmsford knew that the country was vast, and occupation was out of the question. It would seem that the only effective way for the British forces to gain a victory would be to advance on the Zulu capital of Ulundi, attempt to capture their king, Cetshwayo, and smash any intercepting Zulu izimpi (armies) as they went. With that plan in mind, Chelmsford divided his army into five columns. The left, center and right columns would advance on Ulundi from three different directions. A fourth column could be held in reserve to protect Natal from any Zulu surprise attack. A fifth force, the 41st Regiment under Colonel Hugh Rowlands, V.C., would camp at Luneville in the Transvaal, to guard against possible intervention either by the Pedi tribe under Sekhukhune–a known ally of Cetshwayo–or by the Boers. Chelmsford would go with the center column. On January 11, 1879, Chelmsford put his plan into operation as British troops crossed the Buffalo River at Rorke’s Drift and entered the land of the Zulu.

The British invasion forces were soon in deep trouble. Informed by his scouts of the three-pronged British offensive, King Cetshwayo committed some of his available amabutho (regiments) to deal with each of the British forces, but kept most of them concentrated in a single, highly mobile 20,000-man impi under the joint command of inKhosi (princes) Ntshingwayo kaMahole and Mavumengwana, with which he intended to engage each of the slow-moving enemy prongs in turn. On January 22, 1879, a sizable part of Chelmsford’s central column and part of Colonel A.R.E. Durnford’s No. 3 Column ran into Cetshwayo’s main impi at Isandlwana and was annihilated–858 British and 471 native troops were wiped out. With his entire offensive thrown off balance, Chelmsford had to beat a hasty retreat back to Natal.

On the same day of the Isandlwana debacle, Colonel Charles Knight Pearson’s No. 1 Column, working its way along the coast, repulsed a poorly coordinated attack by a Zulu impi at Nyezane. On January 28, however, Pearson learned of Isandlwana and, left to his own devices, dug in at Eshowe for what became a protracted siege.

That left only one active British force in Zululand–No. 4 Column in the northwest, commanded by Colonel Wood–and Wood, like Pearson, chose to take up a very good defensive position on the crest of a hill at Khambula. For the time being, it seemed as if the invasion had come to a halt while Lord Chelmsford gathered his thoughts. In the meantime, he transferred most of Rowlands’ column to Wood’s command, along with the Edendale Troop, Natal Native Horse and 1st Squadron, Mounted Infantry, from what remained of Chelmsford’s center force. Then on March 20, Chelmsford made his request to Wood for a diversion, and Wood prepared to move against the abaQulusi encamped at Hlobane.

At that point, Wood was aware that the abaQulusi were not his only opponents in the area. Recently, the abaQulusi had been reinforced by a contingent of renegade amaSwazi, led by Khosa (prince) Mbelini kaMswati. Most amaSwazi were loyal to the British, but Mbelini, a pretender to the Swazi chiefdom, had broken with them and had allied himself with Cetshwayo. On March 12, Mbelini and about 800 of his followers surprised a company-sized detachment from the 80th (Staffordshire Volunteer) Regiment encamped along the Ntombe River and killed 79 men. Afterward, Mbelini withdrew, taking with him most of the supplies and ammunition he found in the British supply wagons, eventually joining the abaQulusi at Hlobane.

Even with Mbelini’s irregulars, the estimated total of 1,500 warriors on Hlobane was hardly sufficient to threaten Wood’s camp, but their raiding and stealing cattle near the ZuluNatal border was a considerable nuisance and drew strength from Wood’s defensive position. Wood realized that there could be no peace to the northwest of Zululand until the abaQulusi were subdued.

Wood reconnoitered the approaches to Hlobane and then worked out his plan of attack. It would not be easy–the British would have difficulty scaling the steep-sided krantzes (cliffs)–but there were two possible routes to the top. Wood thought that a dismounted cavalry force might be able to lead horses up the western slopes of Zunguin Nek, over the lower plateau, then move on to the upper plateau.

At the eastern end of the mountain lay Ityenka Nek, a high saddle of ground that gave way to steep cliffs and a high rocky terrace, notched and honeycombed with caves. There, a path twisting its way up and across the jumbled rocks was another possible route to the top.

Meanwhile, at his royal kraal (village) at Ulundi, King Cetshwayo had received a message from ‘the Swazi Pretender’ Mbelini, boasting of his success at the Ntombe River, but at the same time urgently requesting that Zulu reinforcements be sent to Hlobane. Recognizing Wood’s column as the greatest remaining British threat in his territory, Cetshwayo was willing to oblige. The warriors of his main impi had taken some time to ceremoniously cleanse themselves after ‘washing their spears’ at Isandlwana, replacing their losses and allowing their wounded time to heal. But on March 24 they were ready to move, and Cetshwayo dispatched them to Hlobane, under the joint command of Khosa Mnyamana kaNgqengelele and the victor of Isandlwana, Ntshingwayo.

On March 26, Wood heard reports that the main impi had left Ulundi and that its probable objective was to attack his camp at Khambula. If that was indeed the case, he knew that the impi would have to take the road that led directly along the southern flank of Hlobane. If the information received was correct, Wood was about to gamble with the safety of his camp by marching on Hlobane. But preparations were made, and on March 27 Khambula was astir long before daylight, as a long column of mounted men rode out of the camp.

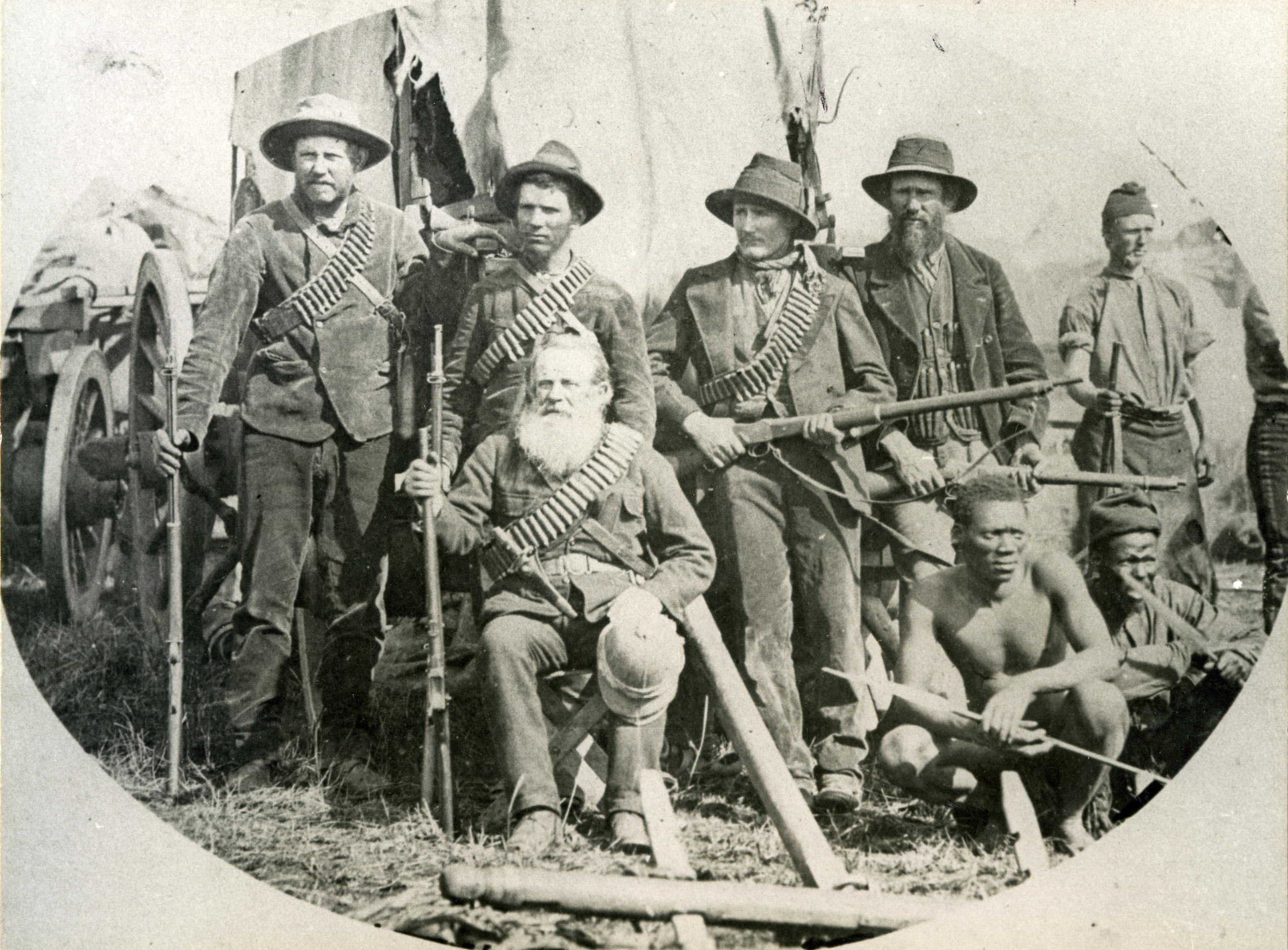

There were 156 men in the Frontier Light Horse (FLH), under the command of Captain Robert Barton of the Coldstream Guards. Petrus Lafrus (Piet) Uys, a Boer farmer who had lost his father and a brother to the Zulus many years earlier, commanded about 40 scouts, including two of his sons. There were 70 Transvaal Rangers and 80 Cape Colony volunteers of Bakers Horse and Lt. Col. Frederick Augustus Weatherley with the Border Horse–about 400 mounted men in all. Also accompanying the expedition were the 277 native troops of the 2nd Battalion of Wood’s Irregulars–mostly local recruits from the Transvaal, supplemented by loyal Swazi warriors–under the command of Major William Knox Leet.

At midday, the British column halted for an hour’s rest prior to making the next leg of their journey–up the foot of the mountain at the western end of Hlobane. Once there, the troops off-saddled near a deserted Zulu kraal, and when the sun set they gathered timber from the huts and made large fires, as though they were camping for the night. When it got dark, they saddled their horses, and then Buller rode toward the eastern end, while a second force led by Lt. Col. John Cecil Russell–comprised of the 1st Squadron, Mounted Infantry, the Kaffrarian Rifles, the Edendale Troop of the Natal Native Horse, a rocket detail of the Royal Artillery and a battalion of 200 Zulu allies (led by Cetshwayo’s disaffected half-brother, Khosa Hamu kaNzibe)–rode toward the lower plateau in the west and bivouacked at the foot of the mountain for the night.

Colonel Wood had left Khambula two hours after the main column, heading toward Hlobane. He was accompanied by his personal staff, Lieutenant Henry Lyson and Captain Ronald Campbell, as well as his political agent and interpreter, Llewellyn Lloyd, along with a number of friendly mounted Zulus and eight mounted men from the 90th (Perthshire Volunteers) Light Infantry.

The next morning, Wood set out with his escort to ride the five miles along the southern foot of Hlobane, following the route taken by Buller and the FLH. He then encountered Weatherley and the Border Horse. Weatherley had lost Buller in a rainstorm that morning. His men, who were not professional soldiers, were wet and cold, and not in a good frame of mind.

Buller had, in fact, already begun ascending the mountain at 3 that morning, despite a blinding thunderstorm that hampered the cavalry’s progress. Dawn revealed another unpleasant surprise: Hlobane’s abaQulusi defenders had erected barricades among the boulders and caves, from which they now opened fire. Two officers of the FLH, Lieutenants Otto von Stietencron and George Williams, were cut down, as were two troopers.

Buller’s column was just visible high on the trail, so Wood ordered the Border Horse to follow it up. Weatherley again lost the trail to the summit, however. Concealed behind boulders and in caves on a rocky terrace, abaQulusi riflemen began sniping at the Border Horse. As Wood’s party came up, an abaQulusi took aim and, just as Wood was expressing his scorn for Zulu marksmanship, opened fire. Lloyd fell back, exclaiming, ‘I’m hit badly! My back is broken.’ While Captain Campbell and an escort were carrying the mortally wounded Lloyd down the slope, Wood’s horse was killed. Wood directed Weatherley to dislodge a number of abaQulusi who were causing the most trouble, but only two of the Border Horse–Lieutenant J. Poole and Sub-Lieutenant H.W. Parminter–responded; the rest insisted that the enemy position was unassailable. Voicing his contempt for their cowardice, Campbell, his aide-de-camp, 2nd Lt. Henry Lysons, and four mounted infantrymen of the 90th charged into a cave. As they entered, Campbell was fatally shot in the head. Lysons and Private Edmund J. Fowler, following close on the captain’s footsteps, shot and killed one sniper; the other escaped through a subterranean passageway.

Campbell’s body was carried back down the hill. Wood had been extremely fond of Campbell and Lloyd and was stunned by their deaths. He lost all interest in the ongoing fight while he concentrated on giving his friends a proper burial. Since the abaQulusi were still sniping at them from the rocks, Wood decided to move the bodies farther down the hill. Weatherley and the Border Horse went in search of Buller’s command, as Wood ordered his Zulu retainers to dig a shallow grave with their assegais. Only when he was certain that his friends could rest without their legs doubled up would he permit the bodies to be lowered into the grave and interred. Wood read the burial service over the bodies while skirmishing went on close behind him.

Seeing some 300 Zulus approaching from the east, Wood had his party ride back to the western end of Hlobane. As the commander cantered up a rise, his Zulu escort called his attention to the plain below. Wood looked…and got the shock of his life. A gigantic force of some 22,000 warriors–Cetshwayo’s main impi–was at the foot of the mountain and starting to outflank the British by going into its traditional ‘buffalo’ attack formation–two ‘horns’ branching around the mountain, the central ‘chest’ advancing directly up the middle and the ‘loins’ holding back as a follow-up reserve. All Wood could do was hope that Buller, who was now at the summit, had also seen the impi‘s approach.

At about that time, Weatherley and the Border Horse had reached the top of the plateau. Weatherley had two sons accompanying his column, and 15-year-old Rupert, who had joined up as a sub-lieutenant, was riding at his side. Rupert had heard his father speak many times of great battles in foreign lands, and with the exuberant enthusiasm of his youth had been looking forward to his first campaign. Weatherley, however, was becoming alarmed by the situation that he saw developing. The terrain was treacherous–not good country for mounted men to be caught in by marauding bands of Zulus. But Wood had insisted that Weatherley and his men go on.

That morning had gone well for Buller on reaching the summit; his native irregulars had just rounded up a herd of cattle and were driving them in a westerly direction. A number of abaQulusi on the plateau declined to close with Buller’s column, as they were not in sufficient strength. It seemed probable that Buller would have no great difficulty in joining with Russell on the lower plateau to the west, after which they could drive the captured cattle back to Khambula via the lower plain.

All went according to plan–that is, until Buller reached the edge of the upper plateau and confronted a steep drop of at least 130 feet, studded with rocks and boulders. Buller discussed the situation with Captain Edward Browne of 1st Battalion, 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot, who commanded a contingent of 20 mounted infantry detached from Russell’s column. Browne reported that Russell had judged it impossible to ascend the steep escarpment that faced his column. As for himself, Buller reckoned that men might be able to scramble down the steep, rocky slope on foot, but to get the horses or cattle down was impossible. It seemed that they would have to turn back and take the long route down the trail that they had come across earlier that morning.

With that in mind, Buller dispatched the FLH commander, Captain Barton, and 30 troopers with instructions to descend the terrace on the southeastern trail and find and bury the men who had been killed in the earlier skirmishes there. Barton was then to locate Weatherley and tell him to make his way back to Khambula by the preceding day’s route. Barton had just left on his mission when Buller saw the great impi below. Buller realized that retreat for Barton or himself in the direction of the previous day’s march was now impossible; the impi was probably still about five miles away, but by the time Barton reached the eastern trail the fast-moving Zulu warriors would be upon him. Buller immediately sent a trooper after Barton to tell him to retire to the north.

Disregarding the cattle, Buller then started to look for a way down from the mountain at the western end. Until then, the abaQulusi and amaSwazi on Hlobane had not been very aggressive. But with the approach of the great impi–coincident with the arrival of reinforcements of their own from the northeast–they took heart and pressed forward in increasing numbers.

Meanwhile, Weatherley’s Border Horse had reached the top of the plateau, skirmishing with the abaQulusi as they made their way upward. As the abaQulusi reinforcements arrived, Weatherley had taken his men along the northern cliffs looking for a place to descend, finding the sides of the cliffs very steep. Crossing the plateau, Weatherley encountered Barton. The Border Horse then fell in behind the FLH, and together they made their way along the plateau and started to descend along the eastern trail. Halfway down, they met the impi coming up. The lower slopes of Hlobane seemed to have turned into a seething mass of black fury.

Weatherley and Barton turned back and tried to cross Ityenka Nek, a saddle of open land between the high cliffs of Hlobane and another mountain to the west. No use: The abaQulusi, keen to recover their cattle and to wreak bloody vengeance upon the British, were swarming all around them. Dressing their line, the British charged, desperately trying to cut their way out to the north. But the abaQulusi stood fast, and the horsemen crumbled before the forest of assegais. About 20 riders did get through, among them Weatherley and Barton. A French member of Weatherley’s Horse named Garnier had just hoisted a wounded comrade on his horse when a Swazi grabbed his leg and took him prisoner. Taken to Mbelini’s kraal on the south side of Hlobane, Garnier eventually escaped and was recovered by Wood’s troops, half-naked and starving, 18 days later. He would later write of his experience as the only European to be taken prisoner during the battle.

Weatherley had lost contact with his son Rupert and refused to leave the boy. Turning back, he found Rupert on some open ground. Weatherley dismounted, heaved the badly wounded boy up onto his horse and turned to face the onrushing abaQulusi. With his arm tightly clasped around his son, he charged into the swirling mass of plumed warriors, who cut the pair to pieces with their deadly blades.

Meanwhile, Captain Barton and 20 others had managed to make their way to the valley, only to encounter the advance party of the Zulu impi–mounted skirmishers of the umCijo ibutho (regiment)—who promptly attacked and quickly killed three-quarters of them. Breaking clear of the assailants, Barton was wounded, his horse had been speared, and he now faced a 20-mile ride back to Khambula. Other survivors stumbled away from the carnage on foot. Barton knew that these men without mounts were as good as dead. Recognizing one of his officers, he reined in his horse and picked up Lieutenant Poole of the Border Horse. Barton’s heavily-laden horse stumbled along for several miles, hotly pursued on foot by a number of the seemingly indefatigable Zulu warriors. Finally, the wounded animal could struggle on no farther. The two Britishers tried to escape on foot, but Poole was overtaken and killed by Chicheeli of the umCijo ibutho. Chicheeli–who claimed to have already killed six other enemies in the fight–then caught up with Barton and, when Barton’s pistol failed to fire, gestured for him to surrender, since Cetshwayo had given orders for his warriors to bring in prominent British officers alive, if possible. As Barton was about to surrender, however, another Zulu shot him. Chagrined at losing his prisoner, but wishing at least to be credited with the kill, Chicheeli finished off the mortally wounded Barton with his assegai.

As the Zulus advanced along the lower plateau, Colonel Buller and his men huddled at the top of the steep, rocky incline that henceforth would be known as Devil’s Pass. Surrounded by sheer cliffs, it was the only way off the mountain. It was a case of scrambling down or being slaughtered by the Zulu hordes.

Before attempting the descent with his troopers, Buller ordered his African levies to make their way down first. They managed to do so, but during their subsequent flight from Hlobane about 100 of them were overtaken and killed by pursuing Zulus. The British cavalrymen then tried their luck on the incline, while Buller and a small rearguard, including Captain Brown’s mounted infantry, did their best to hold the abaQulusi off.

A new recruit to the FLH rode up to join Brown and Buller as they peered over the cliff edge into Devil’s Pass. Mounted on a Basuto pony named Warrior, he had no uniform, aside from the distinguishing strip of red cloth tied around his hat. He was 16-year-old George Mossop, who had run away from home in Greytown at the age of 14 to become a hunter in the Transvaal.

Looking down into the pass, Mossop could see that even if he and his pony could make it down the 130 feet to the ridge, they would still have to descend 700 feet more to reach the valley below–and then somehow make the 20-mile trek to Khambula.

It was a daunting proposition. Men and horses were rolling down into the pass as the abaQulusi crawled over the rocks, jabbing at the horses with their assegais. Several troopers were captured by the abaQulusi, only to be summarily hurled to their deaths from the mountainside. Mossop asked a man standing next to him, ‘Can we get down?’ ‘Not a hope,’ the trooper replied. He then placed the muzzle of his carbine in his mouth and pulled the trigger.

Mossop gave one yell and bounded down the slope, leaving Warrior to his fate. Suddenly, an arm gripped the boy and he looked up into the enraged face of Colonel Redvers Buller. ‘Where is your horse?’ Buller yelled. Mossop pointed back up toward the plateau. ‘Then go and get him,’ shouted Buller, ‘and don’t leave him again.’ More terrified of Buller than the abaQulusi, Mossop started back up the pass for Warrior.

By now, most of the men still on the cliff top were corpses. As the abaQulusi came ever closer, Mossop scrambled down again, dragging Warrior behind him. Although the pony lost his footing and rolled down to the ridge, on inspection he seemed to be all right.

Mossop mounted once more just as the abaQulusi rushed him. Warrior bounded forward down the steep slopes that led to

the valley below. Once on the plain, Mossop came to a stream. Dismounting, he plunged his face into the cold water. Although somewhat revived, he now saw the exhausted Warrior was

in a bad way. Feeling weak himself, the boy lay down beside his faithful mount. No sooner had he done so than he was roused by the sharp cry ‘uSuthu!‘ The Zulus had seen him and were running toward him. Mossop frantically sprang onto Warrior’s back once again, and somehow the injured pony managed to outpace his Zulu pursuers.

Mossop arrived safely at Khambula late in the evening. But his gallant pony died the following morning.

Back on the plateau, Buller worked desperately to save as many of his men as he could. Many of them had fought their way down the deep rocky pass, and so long as there was one man left, Buller would not flee. Time and time again he plunged into the pass to rescue more of his men, take them to the safety of the lower plateau and send them on their way to Khambula. Others were similarly snatched from certain death by Major Leet and Captain Browne.

Most of the Boers had reached the lower plains. Finally, only Piet Uys and his two sons stood with Buller as the men in the pass below managed to make their escape. Unaware that a number of abaQulusi were closing in on him, Uys’ eldest son, Petrus, struggled to calm a frightened horse. Uys raced to his son’s assistance and had just extricated him from the trap when another abaQulusi sprang from some rocks onto Piet Uys’ horse and assegaied Uys in the back, killing him. Another Boer, Andries Rudolf, shot Piet Uys’ assailant and then fled to safety, along with both of Uys’ sons.

With all the men down from the pass, Buller finally made his way over the plateau on to the plains, back to Khambula. What had started as a straightforward raid against the abaQulusi that morning had turned into a bloody massacre of the British forces, thanks to the unexpected arrival of Cetshwayo’s main impi.

Some of the British units had fared better than others. Colonel Russell, whom Wood had expected to provide Buller with some support, had misconstrued a dispatch from his commander and evacuated his position, descending from the lower plateau at the western end of Hlobane onto the plain, and then proceeding in a northwesterly direction to Khambula. Some of the survivors of the Hlobane debacle later regarded Russell’s actions as bordering on cowardice. Russell’s friendship with the Prince of Wales, however, averted any possibility of a court-martial.

Wood and his escort had made their way along the foot of the mountain, also in a westerly direction. Once clear of Hlobane, Wood scaled some high ground and remained there until dusk, watching the retreat. He then made his way back to Khambula.

British casualties on Hlobane numbered 17 officers and 82 enlisted men killed, along with some 100 irregular and native troops. One officer and seven other ranks were wounded. Of the 750 black volunteers of Wood’s Irregulars, only 50 remained after the battle; of the rest, those who had not been killed had deserted. Precise Zulu statistics for the battle are unknown, but they described their own losses as ‘negligible.’

Following the battles of Isandlwana and the Ntombe River, Hlobane was the third and last major Zulu victory of the war. Never again would they be presented with the circumstances that made their victory possible–a British force caught and trapped while on the move and in the open–on so large a scale. Indeed, the very day after Hlobane would see those same victorious amabutho slaughtered in an unwise assault against Wood’s prepared defenses at Khambula.

No eyewitness account is known to have been garnered from the Zulus on Hlobane mountain itself, but an outsider’s perspective was provided after the war by Mehlokazulu, a surviving veteran of the inGobamakhosi ibutho attached to the main impi: ‘The English force went up the mountain and did not see us; we came round the mountain. Those who were on the side of the mountain where the sun sets succeeded in getting out quickly; those who were on the side where the sun rises were driven the other way, and thrown over the krantzes. There was a row of white men thrown over the krantzes, their ammunition was done, they did not fire, and we killed them without their killing any of our men; a great many were also killed on the top, they were killed by the people on the mountain. We did not go up the mountain, but the men whom the English forces had attacked followed them up. They [the British] had beaten the abaQulusi, and succeeded in getting all the cattle of the whole neighborhood which was there, and would have taken away the whole [herd] had we not rescued them.’

One of Buller’s officers, Lieutenant Alfred Blaine of the FLH, would never forget the fight he survived: ‘The Hlobane retreat was a most awful affair. Never do I wish to see another day like it,’ he recalled. ‘We retired well, but I shall never forget the Kaffirs getting in amongst us and assegaing our poor fellows. Some of the cries for mercy from the poor fellows brought tears into our eyes. We lost over a hundred officers and men. No men ever fought more pluckily than the Zulus, they are brave men indeed.’

There had been no shortage of bravery on either side. Five Victoria Crosses were awarded for extraordinary valor at Hlobane–to Browne, Buller, Fowler, Leet and Lysons–as well as five Distinguished Conduct Medals. For their role in the day’s victory, the young bachelor warriors of the umCijo, inGobamakhosi and other amabutho added regimental and personal honors to those already won at Isandlwana–and with them, the eligibility to marry, if they survived the war.

Young George Mossop survived to participate in the great battle of Khambula the next day. Mossop went on to fight at the final major battle of the Zulu War, Ulundi, on July 4, 1879. After the war, he settled back into his old life, becoming a frontiersman and a big-game hunter until his death in 1930.

Today, Hlobane is an open-cast coal mine. A marker was placed on the razorback ridge at the foot of Devil’s Pass to mark the spot where Piet Uys fell. Part of it still remains today. The graves of Captains Campbell and Lloyd have been preserved, and the site marked with a cross and surrounded by a stone wall. The men who died with Colonel Weatherley were later buried by Lt. Col. Sir Baker Creed Russell’s column in August and September 1879. Captain Robert Barton’s remains were buried by Wood in 1880; his gravesite is known to local tour guides familiar with the area. Hlobane has been known to the Zulu since 1879 as the ‘Stabbing Mountain.’

British artist and author William Watson Race and editor Jon Guttman combined their research to recount the Battle of Hlobane. Further reading: The Zulu War, by Michael Barthorp; and Blood on the Painted Mountain: Zulu Victory and Defeat, Hlobane and Kambula 1879, by Ron Lock.

This article was originally published in the June 1996 issue of Military History magazine.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Military History magazine today!