There were terms for rich young women like Mary Jayne Gold in the United States of the 1930s. Newspapers routinely derided her type as “Lisping Lulus” or “Nice Nellies,” the perfect companions for the “Lounge Lizard” young men who seemed the antithesis of the tough Doughboys of the First World War.

Born in Chicago in 1909, Gold was the granddaughter of the man who invented the first cast-iron radiator, and the family grew wealthy from manufacturing steam heating systems. She came of age in the late 1920s, the decade of jazz and “flappers,” where young women enjoyed social freedom unknown to previous generations. The Great Crash of 1929 didn’tinhibit the carefree lifestyle of women like Gold, who, despite her surname, was not Jewish.

She relocated to Europe in the 1930s, settling in Paris, the city glamorized for Americans in the 1920s by the likes of Ernest Hemingway and Josephine Baker. Gold bought a large apartment in the chicest quarter of the French capital and invested in a Percival Vega Gull aircraft. A contemporary recalled that she would “toot around Europe, she would fly to Switzerland for the skiing and to the Italian Riviera for the sun.”

Life was swell for Mary Jayne Gold, but the idyll ended in September 1939 when France and Britain declared war on Nazi Germany. “You felt it was the end of the world, that everything you believed in and everything that had been built up by humanity or decency for centuries was finished,” she reflected in an interview with the French documentary-maker Pierre Sauvage in the 1990s. “And yet, there was another part of me that said, “We’re going to beat ’em.”

Shortly after the outbreak of war, Gold donated her aircraft to the French air force as a contribution to the war effort. Then, like every other person in France, Gold experienced eight months of what is often described as the “Phoney War,” the period of eerie calm in Western Europe, which was shattered in May 1940 when the Germans invaded the Low Countries. Gold joined the exodus out of Paris, one of an estimated two million refugees who fled the capital for the assumed safety of the countryside. Gold’s intention was to head 500 miles south to the Mediterranean port of Marseille and from there catch a ship home. “There didn’t seem much point in staying on,” she reflected.

But en route to Marseille, Gold had an encounter that would change her mind, and her life. In the southern French city of Toulouse, which was an assembly point for European refugees, Gold was introduced by a mutual acquaintance to Miriam Davenport, a native of Boston who had been studying in Paris. Davenport and Gold hit it off at once. Davenport appreciated her new friend’s “splendidly relaxed, no-nonsense air,” and she recalled what Gold told her on that first encounter: “That she was a rich woman and that should I run short of cash, she would love to help out. She was planning to go fetch her little dog from where she had left him on the flight south, then go on to Marseille where she would cable home for money and return to the States.”

Neither Gold nor Davenport left France. They reached Marseille, but once there they decided against returning to the States and instead joined a cause that was virtuous but dangerous, and wildly at odds with their previous privileged and untroubled existence.

Mary Jayne Gold was in the habit of attracting attention with her stylish confidence. Women like Miriam Davenport were struck by her sartorial elegance, and men by her beautiful blonde looks. In Marseille, Gold soon encountered a young Frenchman named Raymond Couraud. It was love at first sight. “I immediately became involved with a young deserter from the Foreign Legion,” recalled Gold. “He and I started a little flirtation for each other, we were keen on each other.”

Couraud was, in fact, half-American, the fruit of a union between a Frenchman and an American woman. They had married in New York in 1919, and Raymond was born in France the following year. Shortly after he turned 18, Couraud enlisted in the Foreign Legion, and in April 1940 his brigade was shipped to Norway to fight the invading Germans. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre for his courage and initiative during the fighting.

After the fall of France, Couraud had been posted to a Legionnaire camp just outside Marseille, but he was disgruntled with the prospect of serving the Vichy regime. “He said he wasn’t going to go back to Algeria [the main Legion base] to make roads for the bloody Vichy,” remembered Gold. “He persuaded me that I should buy a small trawler that he could sail to Gibraltar with twelve other Legionnaires, who also wished to desert, and continue the fight from England.” Gold had by now endowed Couraud with a nickname: “Killer,” on account of the way “he murdered the English language.”

Couraud certainly didn’t resemble a physical killer. Of slim build with spectacles and a grave countenance, Couraud looked more like one of the many bureaucrats in Marseille trying to deal with the throngs of refugees arriving each day in the port. There was also a more sinister side to Couraud that began to emerge in Marseille as he slowly shed the discipline instilled in him by the Foreign Legion. He was vain and selfish, a thrill-seeker who thrived in a combat theater but who, deprived of action and excitement, quickly became restless and reckless.

Gold agreed to fund her lover’s audacious plan to buy a boat and sail to the British territory of Gibraltar, on the southern coast of Spain. But before the scheme could be launched, Couraud was arrested by the Legion for desertion and locked up in Marseille’s military prison in August 1940.

Davenport was relieved. She considered the Frenchman a malign influence on her friend, and without Couraud to lead her astray, Gold would be a heartening companion in a time of tension and uncertainty. The pair met for lunch, and Davenport told Gold she had decided to remain in Marseille and try in some way to help the Jewish refugees who were becoming increasingly anxious to escape to America. She knew she could confide in Gold, who was “passionately anti-Nazi…. Even her poodle, Dagobert, would bark furiously whenever one muttered ‘Hitler! Hitler!’”

They wrote to a contact in the U.S. consulate in Marseille, “expressing our interest in being helpful to refugees. In return we got a curt reply; he had all the help he needed, thank you.” A similar approach to the American Red Cross was also unsuccessful.

One day in the middle of August 1940, Davenport and Gold were having coffee in their favorite café, the Pelikan, close to the U.S. consulate, when, as Davenport recalled, they heard gossip that an American with “money, access to visas, and a list of people he was supposed to rescue” had recently arrived in Marseille and was staying in the Hotel Splendide. The name of the American was Varian Fry.

Davenport went to see Fry the next day with a list of artists and intellectuals who had angered the Nazis and were now in Marseille looking for passage to America. Among the names mentioned by Davenport were the satirist Walter Mehring, whose political poems were favorites of the raucous Berlin cabarets so detested by the Nazis; Hitler’s biographer, Konrad Heiden; and the German novelist Heinrich Mann.

Fry was impressed with Davenport. She was as well-organized as she was well-connected. “Would you be willing to be named Secretary General of a committee that we are planning to set up?” he inquired. He could pay her 750 francs a week (approximately $17, or $340 today), and in return she would help interview some of the hundreds of refugees to determine who were genuinely at risk from the Nazis.

A married man, the 32-year-old Fry was an ardent anti-Nazi (and also anti-Communist) and one of the first American journalists to warn of what was taking root in Germany, having visited Berlin in 1935. On witnessing one anti-Jewish demonstration, he wrote an article for the New York Times in which he described the indiscriminate violence meted out to Jews and the indifference of the German police.

As Germany invaded the Low Countries and France, he anticipated the refugee crisis, and in June 1940 Fry and 200 prominent Americans from the world of arts and academia formed the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC). First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was approached that same month. She endorsed the ERC and also used her influence to procure a number of emergency visas for endangered refugees.

Fry arrived in Marseille in early August 1940 with the visas as well as $3,000 and a list of approximately 200 refugees to rescue, most of whom were Jews. What Fry didn’t possess were contacts, which was why he jumped at the chance to recruit Davenport to his cause.

He was less impressed, however, the first time Davenport introduced him to her friend, Mary Jayne Gold. Intense and earnest, Fry initially sized up Gold as a woman without substance. “She’s just another rich playgirl, probably one with a passion for dukes and duchesses and whose friends are ultra-reactionary,” he told Davenport.

The distaste was mutual. “He was stiff and standoffish…and rather dry and clipped in his conversation,” recalled Gold. “Miriam had praised him to the heavens. I told her he looks like a Salvation Army captain.”

Davenport was determined to find a role for Gold in the ERC, and eventually she persuaded Fry to give her friend a second chance over a coffee. “I made a few remarks about the evil of the fascists and Anti-Semitism and all that,” remembered Gold. “I was putting my best liberal foot forward not to be this supercilious playgirl who was trying to infiltrate the committee with money.”

Gold won over Fry, who wrote after the war that she was “a made-to-order charmer…young, blonde, and beautiful,” and he believed such a vivacious character might be an asset in circumventing the notorious French bureaucracy with her “feminine wiles”—but admitted that the main reason he accepted her into the ERC was her money.

It hadn’t taken long for Fry to appreciate that there were far more than 200 refugees in need of rescue. There were thousands milling about Marseille, most without the financial means to pay for passage out of France. “As the days wore on I became more and more depressed by the number of endangered people who deserved help but were unknown to the old-boy network,” said Davenport.

Fry wanted to broaden the ERC, but to do that required money: Gold’s money. She gave the ERC an initial sum of $3,000 (approximately $60,000 today) to establish what Davenport called the “Gold List,” dedicated to helping the poorer refugees.

Gold’s financial and moral commitment to the ERC soon became invaluable, as Fry explained in a letter to his wife in 1941. “It would be hard to find a better person for the job we had in mind than Mary Jayne,” he wrote. “She has already given us thousands, and she is more interested in our work than anyone else I know.”

Gold joined Davenport in the ERC office in downtown Marseille. Each day they interviewed dozens of refugees who were desperate to leave France. “You would ask if they had their documents and then ask if they were valid, same with visas,” recalled Gold. “Then you had to ask the 64-dollar question: ‘What have you done to put you in danger with the German authorities?’”

It was the first time in her life Gold had encountered humanity in its most wretched and vulnerable state. “The interviews were touching in a way,” she reflected. “These people, some were very simple, but they were very brave. They hadn’t written books or painted pictures…the people I interviewed were rank and file.” They were German students who had voiced their opposition in lecture halls to Hitler, Austrian trade unionists who had given out tracts in the street, or simply Jews from any number of European countries now under the Nazi yoke. But Gold and the other interviewers could not let emotions cloud their judgment. Only those considered most at risk were given visas, and Gold became accustomed to the look of bitter disappointment on the faces of those turned away.

One of the first prominent refugees to leave was the satirist Walter Mehring, who set off for Portugal in September 1941 with an American visa and a forged Czech passport—but still wearing the tattered clothes in which he had traveled across Europe. As he had a drink in a café in Perpignan, a French city close to the Spanish border, Mehring was detained by a plainclothes policeman who thought he looked suspicious. Unable to produce a safe-conduct pass, Mehring was held in an internment camp pending further inquiries. Fortunately, he got word to the ERC, and Fry dispatched a lawyer—paid for by Gold’s money—to secure Mehring’s release. “It had been our fault for not seeing to it that Mehring was properly dressed for his journey to freedom,” reflected Davenport, who was “instructed to go shopping with him to make sure that he was dressed like a gent.”

Mehring eventually made it across the border, as did an increasing number of refugees in the fall of 1940. But the Vichy French authorities were now aware of the ERC’s activity and lodged a complaint with the U.S. consulate. Fry was summoned and shown a communication from the State Department, which had been received via the embassy in Vichy. Reflecting the fact that America was still technically neutral, it stated: “This government cannot countenance the activities as reported…in evading the laws of countries with which the United States maintains friendly relations.”

The Vichy regime also pressured neutral Spain and Portugal to be more proactive in stopping the steady stream of refugees arriving from France either by boat or foot. As a result it became harder for the ERC to obtain visas for these countries.

Then Britain came to the aid of the ERC. Scores of British soldiers stranded in France after the German Occupation had made their way south and were hiding in Marseille and the surrounding countryside, looking for a way to get into Spain and eventually back home. Sir Samuel Hoare, Britain’s ambassador to Spain, asked for Fry’s assistance in getting the soldiers across the border, and in return his government donated $10,000 to his organization.

The ERC was aware it was under surveillance from the French authorities, so, in October 1940, Gold rented a large villa a few miles outside Marseille. The villa was secluded, lacking even a telephone, and it became a haven for staff and some of the refugees. That same month, Fry accepted onto the staff a Frenchman, Daniel Bénédite, whom Gold hadrecommended to the ERC—an indication of the esteem in which she was now held by Fry. “Danny had worked in the prefecture [so] he knew the officialese language,” remarked Gold. “He could write letters in the proper way to any official person that Fry had to deal with. He knew the lingo and how to behave.”

For several months Gold’s money and her diligence had contributed greatly to the ERC’s success in smuggling hundreds of refugees out of France. It had helped that her lover, Raymond Couraud, had been languishing in a military prison. But he was released in De-cember 1940, and the infatuated Gold soon fell under his malign influence once more.

Couraud had no intention of shipping out to Vichy-run Algeria with the Foreign Legion. He deserted for a second time but, this time, joined a Corsican gang involved in the Marseille underworld.

“For a short while, I hoped he would work in the illegal activities of the ERC but Killer just hated all those intellectuals,” reflected Gold. The antipathy was mutual. Asked to make a choice, Gold chose her heart over her head. “I was forced to withdraw from the more noble enterprise and so became a gangster’s moll of sorts,” she admitted.

Gold’s love blinded her to the true character of Couraud until he stole her diamonds. She came to her senses and dumped the Frenchman. “Realizing that he was now more or less washed up with me…he decided it was time he left for England to continue the good fight,” said Gold.

The ERC was only too pleased to get Couraud out of France and out of Gold’s life. The committee facilitated his passage into Spain and then on to Britain, where he joined the commandos and was later commissioned into the Special Air Service [SAS] regiment, the elite British unit whose expertise was in daring raids behind enemy lines. With the SAS he again demonstrated his Jekyll and Hyde character; he was decorated for gallantry by the British but eventually dismissed from the regiment for disobeying orders.

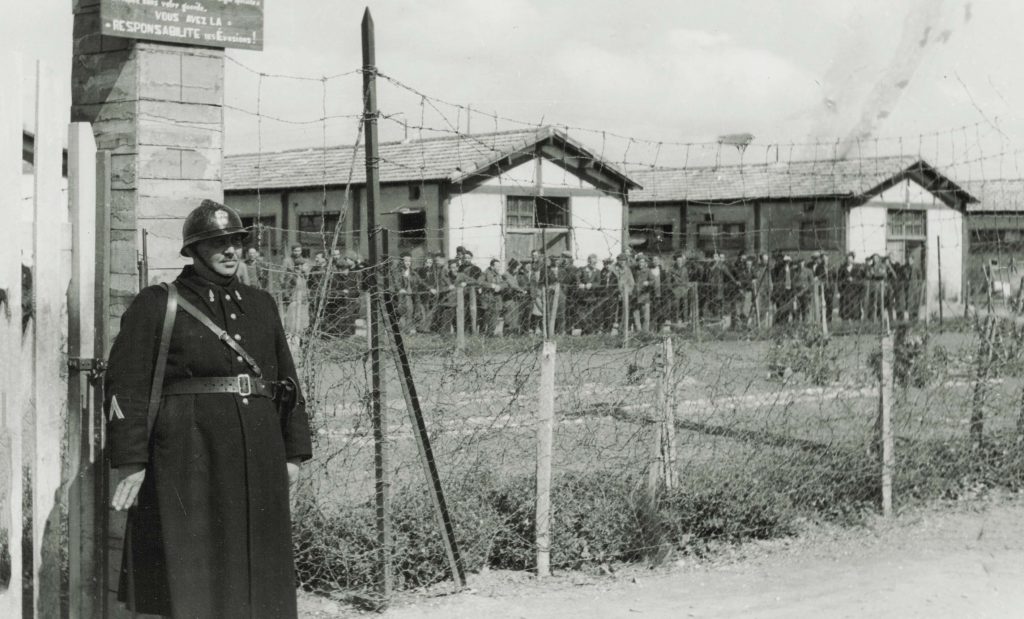

With Couraud gone, Gold was no longer conflicted, and she undertook a perilous mission on behalf of the ERC to a concentration camp close to the Spanish border. The camp, Le Vernet, held thousands of “undesirables,” mainly foreign men considered a threat to public order. Among their number were four Germans who were on Fry’s list to receive American visas, which were waiting for them at the consulate in Marseille. The challenge was how to get the quartet out of the camp. Fry asked Gold to deploy her “feminine wiles” on the camp commandant, a Frenchman with a reputation as a ladies’ man. “I was rather nervous about the whole thing,” admitted Gold, who nonetheless dressed in her most stylish outfit and took a train to the camp. She captivated the commandant from the first moment, and he readily agreed to release the prisoners—but on one condition. “He asked me if I would have dinner with him…he said he knew a little restaurant and he would pick me up.”

Gold accepted the invitation, but the commandant never showed. Unaccustomed to being stood up, Gold returned to the concentration camp and was met by the apologetic Frenchman, who told her: “Mademoiselle, I can assure you I would rather have had dinner with you but I had to dine with the Gestapo.”

Gold knew that the four prisoners were wanted by the Gestapo. She had to act fast and spring them from the camp before the Nazis began examining the prisoners’ files. She feigned disappointment at the canceled date, and the chivalrous commandant, embarrassed that he had upset a lady, ordered the immediate release of the four men as a token of his esteem.

Gold remained with the ERC throughout the summer of 1941. Twice she was arrested, once with Fry, and eventually Vichy French authorities expelled the pair, with the tacit support of the U.S. State Department, in September 1941. They returned to the United States, as did Miriam Davenport, who had left Marseille in late 1940 to fetch her sick fiancé from Yugoslavia. The Vichy government refused to grant them a visa to return to France, and they were forced to wait in Portugal before eventually securing passage across the Atlantic in December 1941.

Danny Bénédite and his English wife, Theodora, took over the committee, moving its headquarters to the countryside but continuing to facilitate the escape of refugees from France. In total an estimated 2,000 refugees escaped the Nazis through France thanks to the work of the ERC.

Postwar life was anticlimactic for both Fry and Gold. Fry divorced and remarried and divorced again, moving to work at a Connecticut high school where he taught Latin and Greek. Shortly before his death in 1967, Gold wrote to him and concluded her letter by saying, “Well, we shared our finest hours, my friend.”

Gold, who never married, died at her home in Saint-Tropez on the French Riviera 30 years later, in her 88th year, two years before Miriam Davenport, with whom she had stayed in regular contact. For the pair, their months in Marseille had been the most meaningful of their lives. It would be an exaggeration to say that they risked their lives to help smuggle refugees out of France, but they certainly risked their liberty.In a war of shocking inhumanity, these two young women demonstrated that conflicts are often won by compassion as well as courage.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of World War II.