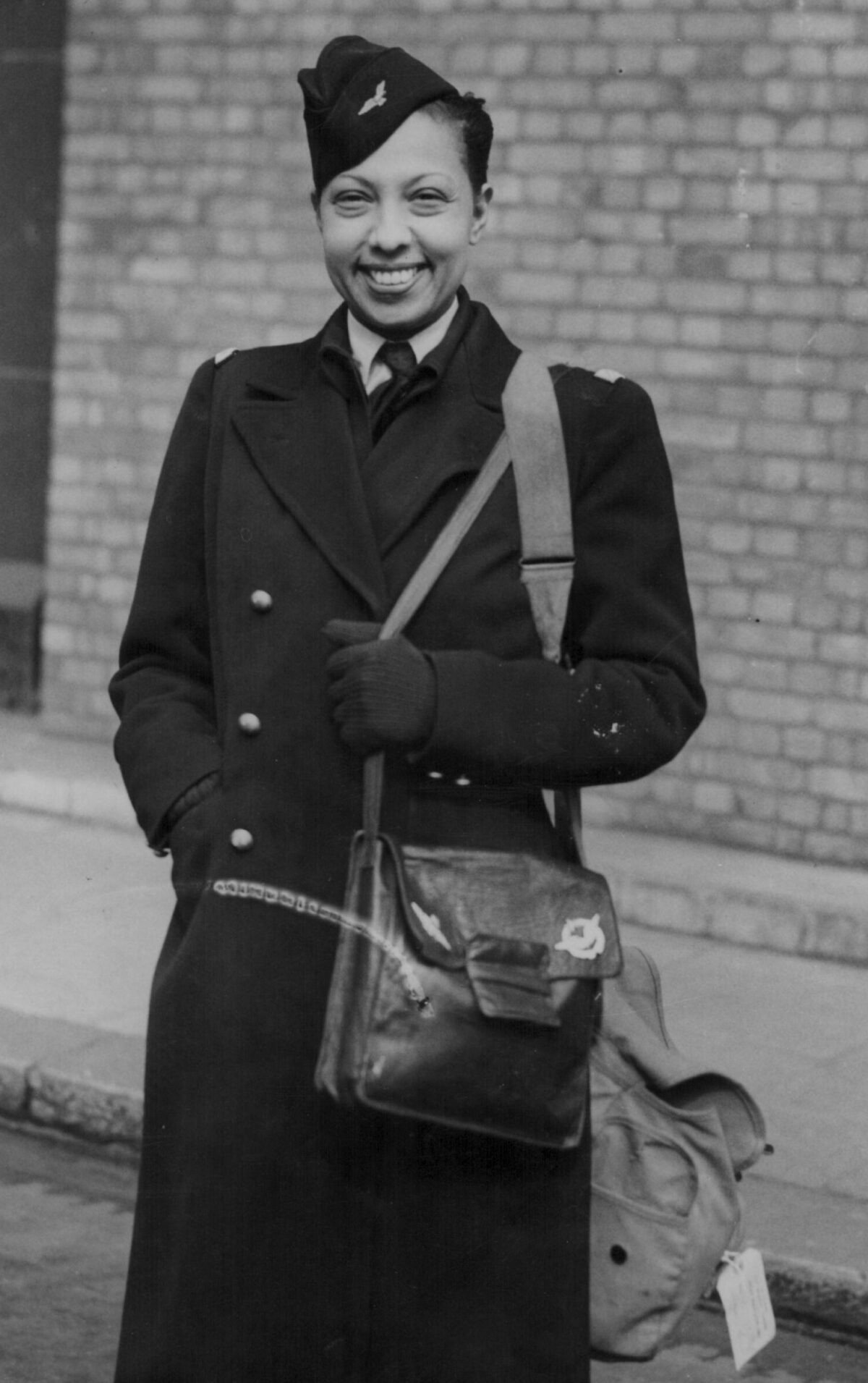

American-born Josephine Baker has become the first Black woman inducted into the French Panthéon, the nation’s hallowed mausoleum of heroes and France’s highest honor.

The push for Baker to be honored in the Panthéon began in 2013, and on Tuesday the entertainer, civil rights activist, and French Resistance hero joined the likes of 80 other luminaries, including Voltaire, Victor Hugo, and Marie Curie.

At the request of her family, Baker’s body will remain in Monaco and her presence in the Panthéon will be commemorated with a plaque on a cenotaph. The symbolic casket, reports the New York Times, carried soil from the United States, France, and Monaco — places that shaped Ms. Baker’s life.

Standing before Baker’s flag-draped coffin, French president Emmanuel Macron presided over the ceremony, declaring that “France is Josephine.”

“She broke down barriers,” Macron continued. “She became part of the hearts and minds of French people … Josephine Baker, you enter the Panthéon because while you were born American, deep down there was no one more French than you.”

Born Freda Josephine McDonald, Baker grew up amid Jim Crow and racial segregation in St. Louis, Missouri, before moving to New York City as a teenager to perform with an all-Black dance troupe. It was there that Baker was discovered by a talent scout from Paris and in 1925, at the age of 19, she moved to the French capital.

Almost immediately, her love affair with the European nation began.

“When I was a child and they burned me out of my home,” she told the crowd during the March on Washington in 1963. “I was frightened and I ran away. Eventually I ran far away. It was to a place called France. Many of you have been there, and many have not. But I must tell you, ladies and gentlemen, in that country I never feared. It was like a fairyland place… when I was young in Paris, strange things happened to me… I could go into any restaurant I wanted to, and I could drink water anyplace I wanted to, and I didn’t have to go to a colored toilet either, and I have to tell you it was nice, and I got used to it, and I liked it, and I wasn’t afraid anymore that someone would shout at me and say, ‘******, go to the end of the line.'”

For the next decade Baker became a staple among the city’s intellectual and artistic elite, becoming a “fixture in shows at Les Folies Bergères, a famous music hall. She was a symbol of the Jazz Age, dominating France’s cabarets with her sense of humor, her frantic dancing and her iconic songs like “J’ai Deux Amours” or “I Have Two Loves,” referring to “mon pays [my country] et Paris,” writes NPR.

In France Baker found the dignity and freedom so often denied to Black men and women in the United States, and as Nazi Germany invaded her beloved adopted nation, the entertainer was determined to fight back.

Before the fall of France in June of 1940, Baker, alongside French actor Maurice Chevalier, performed for French troops stationed along the Maginot Line.

Refusing to dance for the Nazis, Baker used her influence as a shield—stashing weapons and hiding Resistance fighters and Jewish refugees at her chateau, Les Milandes, outside the French neighborhood of Lapeyre.

Laurent Kupferman, who wrote and directed the documentary “Josephine Baker, a French Destiny,” told NPR that the entertainer used her fame to glean information at Axis embassies and that she undertook spy missions, passing between free France in the south and the occupied Vichy zone.

Despite her stardom, her visits home to America were punctuated by the continued humiliations of segregation and discrimination, leading her to become a vocal civil rights activist in her later years.

“I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents,” she told protesters at the March on Washington rally as she stood alongside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad.”

In 1975, Baker passed away at the age of 68 after collapsing on stage during a performance in Paris. In the subsequent days, the streets of Paris thronged with thousands of fans saying their goodbyes.

“She did not defend a certain skin color,” Macron said on Tuesday. “She had a certain idea of humankind and fought for the freedom of everyone. Her cause was universalism, the unity of humanity, the equality of everyone ahead of the identity of each single person.”