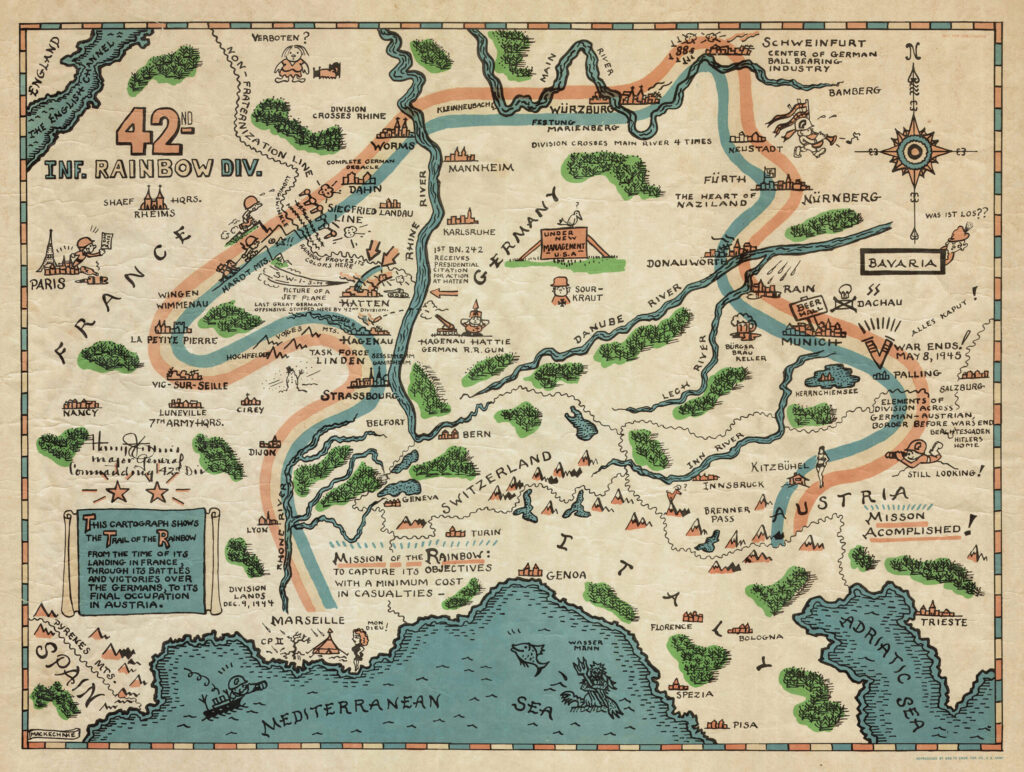

As Allan W. Ostar approaches his 100th birthday, he can look back with pride on a career as an academic administrator and education consultant. For many years, Allan was president of the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. But, as a teenager in 1944, he joined the U.S. Army’s storied 42nd “Rainbow” Infantry Division, which landed in Southern France in December 1944. Moving north through bitter winter conditions, the 42nd repulsed Nazi Germany’s “Operation Northwind” offensive, then attacked through the Hardt Forest, pierced the Siegfried Line, and crossed the Rhine River. In late April 1945, after battling hand-to-hand to conquer Schweinfurt, Rainbow G.I.s arrived at the gates of Dachau concentration camp.

You were born in East Orange, New Jersey, in 1924 and were still in high school when World War II started. When did you graduate?

1942. After I graduated, I went to Penn State, a land-grant university where everybody took ROTC. I was in the ROTC band, on the saxophone. During World War I, my father was an army musician playing the cornet. He was in the band that toured with President Wilson when Wilson did war bond speeches.

How long did you stay at Penn State?

One year. I had joined the Enlisted Reserve Corps. I didn’t want to wait until I was drafted. There was an electrical engineering professor who said, “It’s going to be very helpful to you to take my course in radio.” I took his course and got the certificate. So, when I went on active duty, they sent me to Camp Crowder, Missouri, to become a radio operator. I learned to climb poles and operate switchboards, telephones, and radios.

Then they told me, “You’re going to have to be driving a communications jeep.” But, I said, “I never drove, my parents never had a car.” They said, “Ah, you’re just the guy we’re looking for. We’re going to teach you the army way.” So, I got an army driver’s license for the jeep. Learned how to drive on a 45-degree angle. Then one day they said, “We’re going to put you in the ASTP—Army Specialized Training Program—at the University of Denver to study engineering.”

So, you were back in college through 1943.

Until General [George C.] Marshall decided that they needed infantry much more than they needed college educations. They closed almost all the ASTP units and assigned us to combat divisions.

Where did you get assigned?

The 42nd, the Rainbow Division, Camp Gruber, Oklahoma. Our division commander’s name was [Major General] Harry Collins. I was training as an infantryman, assigned to K company, a rifle company, when the personnel office discovered that I had this radio operator qualification. So, they reassigned me to communications in Headquarters Company, 242nd Infantry Regiment.

When and how did you travel overseas?

Late November ’44 on a troop ship, a converted freighter. They needed troops in Europe, so they didn’t wait to send the whole division. They sent our three infantry regiments, without our artillery, support services, Signal Corps. Crossing the Atlantic was pretty bad. Three of us had to share the same bunk. So, we took turns sleeping, took turns eating. Almost everybody got seasick. Disembarked in Marseille.

Where did you go then?

We had to go through the Vosges Mountains because they needed troops north. It was very icy. I’m driving along the side of a mountain with a big drop-off on the right. I went into a spin. I wouldn’t be talking today if the spin had taken me over the side. I’ll never forget this: The motor pool sergeant came roaring up. He just chewed me up and down because I had banged up his beautiful brand-new jeep.

The 42nd was part of Task Force Linden (under Brigadier General Henning Linden, the Rainbow’s assistant division commander), which entered combat in the vicinity of Strasbourg, France. What was your involvement in the fighting?

Close-in artillery support. Within sight of German troops. The forward observers are right at the front lines or in front of the front lines calling in the artillery support. At first, I had a backpack radio which was not very reliable. So, we relied more on wire connections. I had a rack on the back of a jeep to hold the spool of wire. I would also carry a sound-powered phone plus the radio so we could communicate firing orders on troop concentrations, artillery positions, machine gun nests. We were almost always under fire.

What were weather conditions like?

Very, very bad. It was reported later that it was one of the worst winters they’d ever experienced in Europe. It was cold, wet snow, sleet. We were not well equipped. We had field jackets and a sweater and gloves. That was all you had in terms of the cold. Some of our heaviest casualties came from what they call trench foot.

Did you ever have trench foot?

One reason I did not was a sergeant in our section who had been stationed in Alaska. He told us how to avoid trench foot. Always carry an extra pair of socks and, when they get wet, put ’em under your armpits to help dry them out. If you could change your socks, you could avoid trench foot.

In February 1945, Task Force Linden came under attack during the German “Operation Northwind” offensive.

My little piece of that was a railroad station in a little town called Rittershoffen. My buddy Kenneth Schultz and I were in the upper floor of the station to set up communications when the Germans attacked. We had a bird’s-eye view. We see these big Panthers [German tanks] coming at us. Kenny Schultz and I had to stay, relaying orders to direct fire to stop the tanks.

We finally got the order that we could leave. We grabbed the crystals out of our radio, ran downstairs, and jumped in the jeep. There were holes in the jeep, but it ran. It didn’t look like we were going to get away, but a platoon of tank destroyers saved our lives. I’ll never forget those Black soldiers who stayed at their posts in those tank destroyers and allowed us to escape. If they hadn’t been there, I wouldn’t be here.

After rest and refit, the Rainbow Division continued north. Describe what that was like for you.

On almost the very first day we went back into combat, our company commander, Captain Kohler, was killed. He was out in front setting up observer posts. A German mortar managed to kill him. And that was a blow to our morale. He was a heck of a good guy. So, Dobson, our first sergeant, got a battlefield commission. Dobson helped me. In the [Vosges] mountains you could only go so far with the jeep. You had to carry everything. I’m a little guy carrying the radio, the wire, the phone. I may have even had an M-1. I got to the point where I just couldn’t move, and he grabbed some of the stuff I was carrying. One time there were mules, carrying supplies and equipment. And that helped a great deal.

Tell me how your unit got across Rhine.

On boats. We heard these trucks coming down the road and they were gray-painted navy trucks pulling trailers with landing boats on ’em. What the hell is the navy doing here?

What was the going like once you crossed?

Well, there were firefights, but we were moving pretty fast. At this point, the Germans were retreating. We were all headed for Munich. But before you get to Munich, there’s an airfield. I remember some of the soldiers were jumping on top of the Messerschmitts to get souvenirs. But I headed for the headquarters building in my jeep. I get to the building, and here is the base commandant. He was in no mood for fighting. He surrendered to me, a private first class. I don’t think I was a corporal yet.

I know that it can be difficult to talk about, but what do you remember about reaching Dachau concentration camp?

Bodies stacked up like cordwood outside the gate. I saw these boxcars with all these bodies, and it was just horrible. You see these emaciated [bodies] not much more than a skeleton. I found a dead German soldier; it might have been one of the guards. He had a belt buckle [inscribed in German] “God is with us.” How could anybody who believed in a God believe they could treat human beings the way these people had been treated?