ON APRIL 29, 1945, just as the U.S. Army’s 42nd and 45th Infantry Divisions were poised to capture Munich, birthplace of the Nazi Party, men from each outfit were ordered to split off and secure a concentration camp 10 miles from the city. Neither the camp’s name—Dachau—nor the term “concentration camp” meant much to these soldiers. The Nazis had hidden the full magnitude of the Holocaust, and rumors of the mistreatment of Jews and political dissidents were so incredible that “when I heard such stories back in the States I never believed them,” Lieutenant William J. Cowling III explained. Lieutenant William P. Walsh expected Dachau to be akin to an American POW camp he had seen in upstate New York, and from a distance, the compound looked benign—neat and orderly. It reminded Lieutenant Colonel Walter J. Fellenz of “a wealthy girls finishing school in the suburbs.”

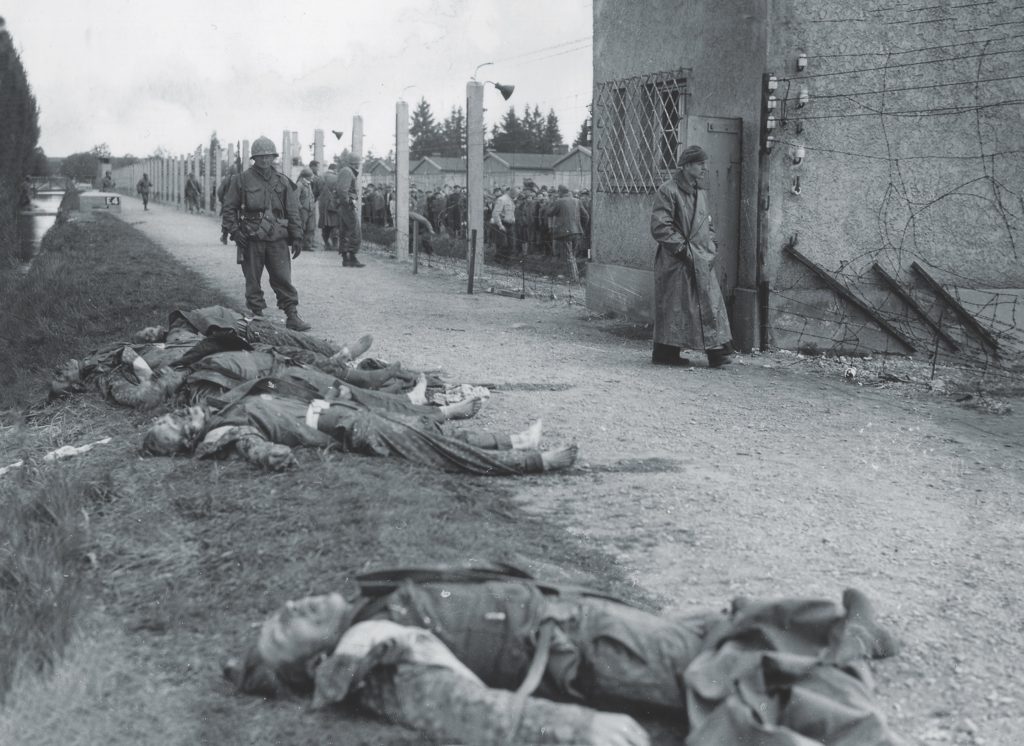

When a 45th Division company under the command of 25-year-old Lieutenant Walsh approached the camp, the men spotted 39 railcars, mostly boxcars and gondolas, parked on a siding. At first glance, the cars appeared to contain piles of dirty clothing, but as the men drew closer, they saw that the soiled laundry was actually the corpses of hundreds of concentration camp inmates—2,310 of them, as it turned out. Some had been shot or beaten, but most had died of starvation. The emaciated bodies shocked these battle-hardened veterans. “Honest,” Lieutenant Cowling wrote to his parents, “their legs and arms were only a couple of inches around and they had no buttocks at all.” Colonel Fellenz, a 28-year-old 42nd Division battalion commander, estimated the bodies weighed only 50-60 pounds each. What haunted these soldiers most, however, were the eyes of the dead. To Private John P. Lee, their death stares seemed to ask the G.I.s: “What took you so long?”

The instantaneous reaction was rage, and incensed soldiers swept through the camp, exacting revenge against the German guards they held responsible. In the months to come, an embarrassed U.S. Army was forced to decide if this retribution was a war crime, an excusable if regrettable response to horrors beyond human comprehension, or well-deserved vigilante justice.

DACHAU WAS THE NAZIS’ FIRST concentration camp, established in March 1933, only weeks after Hitler came to power. Originally intended to house political prisoners, it became an integral part of the Nazis’ attempt to use as slave labor and exterminate Jews and others Hitler deemed undesirable. Since then, 228,930 inmates had passed through its gates, which bore the slogan, “Arbeit Macht Frei” (work makes you free). The fanatical SS ran the camp, and the compound contained an SS training center. In the first four months of 1945 alone, 14,700 inmates had died there.

On April 14, 1945, SS commander Heinrich Himmler ordered Dachau’s inmates evacuated to other camps as he tried to hide the human evidence of Nazi depravity from the approaching Allied armies. That month, thousands were removed on foot or by rail, dropping the camp’s population from 67,665 to 31,432, but the Americans reached the camp before the evacuation could be completed. Those who remained hailed from 40 nations, with the majority being Poles (9,082), Russians (4,258), and French (3,918). The precise number of SS guards and other German soldiers in the camp when the Americans arrived is unknown, with estimates ranging from 100 to 300. Many Germans had fled Dachau in the preceding days to avoid capture.

At the rail siding, Lieutenant Walsh fumed, admittedly “worked up” at the sight of the corpses. When four Germans approached with their hands raised, Walsh motioned them into a boxcar. He ordered Private Harry Crouse to bring over his Browning Automatic Rifle, but before Crouse got there, Walsh shot the prisoners with his pistol. Private Albert C. Pruitt, 23, finished them off with his rifle, claiming, “I never like to see anybody suffer.” Moments later, an SS man wearing a Red Cross armband surrendered to Walsh. Walsh had the German lead Walsh’s men toward the camp, but Walsh claimed the man tried to escape and was shot.

At about the same time, Brigadier General Henning Linden of the 42nd Division and Lieutenant Cowling, his aide, neared the camp entrance. Both men were on edge because they had seen what the railcars held. Under a flag of truce, the camp commandant, Heinrich Wicker, walked toward them. Cowling hoped the commandant “would make a funny move so I could hit the trigger of my tommy gun,” but Wicker simply surrendered the camp. He told Linden that there were about 100 guards inside and that he had ordered them not to fire on the Americans.

The surrender unleashed pandemonium among inmates, and after-action reports and news stories paint a vivid picture of the emotional liberation. General Linden described “a wave of joyous enthusiasm to the extent that the whole fence was lined with a yelling, seething mass of prisoners.” To Colonel Fellenz, “The noise was beyond comprehension!… Our hearts wept as we saw the tears of happiness fall from [the inmates’] cheeks.” Hundreds broke through fences to embrace their liberators. “There is nothing you can do when a lot of hysterical, unshaven, lice-bitten, half-drunk, typhus-infected men want to kiss you. Nothing at all,” Time correspondent Sid Olson reported.

Reality tempered joy, and the inmates’ physical condition stunned the Americans. “Gandhi, after a thirty-day fast, would still look like Hercules when compared with some of these men,” Private Harold Porter wrote to his parents. Some inmates were too weak to greet their liberators. “So many men were sick and possibly dying of starvation and beatings,” Olson reported, “that they merely lay or leaned or sat shoulder to shoulder, too weak to do more than grin glassily.”

Several inmates were killed when they brushed against an electrified fence, and the sight of one such death horrified Fellenz. “It was heart-breaking to see the poor fellow electrocuted when freedom was within his grasp,” he wrote. As the soldiers advanced through the camp, they found a crematorium and a gas chamber. Fellenz entered a warehouse containing thousands of corpses “thrown one on top of the other like sacks of potatoes.” The sight and odor made him vomit uncontrollably. In a letter home, Cowling summarized the men’s emotions. Liberating Dachau, he wrote, was the “most…exciting, horrible and at the same time wonderful experience I have ever or probably ever will have.”

INSIDE THE CAMP, Lieutenant Walsh rounded up about 100 German prisoners. He segregated the SS men from the other Germans and herded them into the camp’s coal yard, an open area surrounded on three sides by 10-foot-high masonry walls. Walsh lined up 50 to 60 SS prisoners against the back wall, and ordered Private William C. Curtin, 22, to cover them with his light machine gun. Weapons at the ready, other G.I.s also kept a close eye on the Germans. Abruptly, Curtin opened up, firing three long bursts, and the prisoners dropped to the ground. Other soldiers also fired, including 25-year-old First Lieutenant Jack Busheyhead, Walsh’s second in command.

Walsh’s battalion commander, 28-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Felix L. Sparks, heard the shots and rushed to the coal yard. He fired his pistol into the air to get the men’s attention, ordered them to cease fire, and booted Curtin away from his machine gun. “What the hell are you doing?” Sparks asked Curtin, who was crying hysterically. Seventeen SS men were dead; other badly wounded Germans lay on the ground, but the doctor in Sparks’s battalion, First Lieutenant Howard Buechner, refused to treat them. Sparks rounded up German medics to render aid.

The soldiers disagreed on what had prompted the shooting. Curtin insisted Walsh had ordered him to shoot, yelling, “Let them have it,” and Lieutenant Daniel F. Drain confirmed this. Walsh denied it. Walsh asserted that he had told Curtin to fire only if the Germans rushed the Americans and that Curtin had opened fire only when the Germans prepared to advance on the G.I.s. Other G.I.s said no order was given or needed. “It was the general feeling among all of the troops…that no prisoners would be taken,” Busheyhead said. Private William L. Competielle agreed. “The word just got around that they were going to shoot all the SS’ers.”

A short distance away, inmates pointed to a guard tower adorned with a white flag and told Sergeant Henry J. Wells that SS men were hiding inside. Wells, who spoke German, fired a burst from his submachine gun through the tower door and ordered the guards to come out. About a dozen exited, with Wells forcibly removing one German. The prisoners were lined up by the tower.

About 10 G.I.s guarded these prisoners. One American opened fire, and “after somebody commenced firing, everybody started firing,” Wells said. Seven SS guards were killed. A G.I. walked among the fallen Germans, shooting his pistol into their bodies. One Polish inmate, Marion Okrutnik, contended that the Americans fired only after a German had reached toward his left armpit as if going for a concealed pistol. Once the first shot was fired, the other G.I.s fired because they “felt that something on the part of the enemy must have gone wrong which was observed by friendly soldiers,” said Wells, who admitted joining in the shooting.

Throughout the camp, inmates sought out guards, beating and bludgeoning an unknown number, and U.S. soldiers turned a blind eye. “We watched with less feeling than if a dog were being beaten,” wrote David Max Eichorn, an army chaplain. An inmate shot two Germans with a rifle issued to 24-year-old Private Peter J. DeMarzo. DeMarzo denied lending his weapon to the inmate and claimed two Russian inmates had snatched it from him.

Few tears were shed for the slain guards. “God forgive me if I say I saw it done without a single disturbed emotion BECAUSE THEY SO HAD-IT-COMING,” Captain David Wilsey wrote to his wife. In a letter to his parents, Lieutenant Cowling asked, “How can they expect to do what they have done and simply say I quit and go scot free?” It was the corpses in the railcars that had incited the soldiers, Lieutenant Harold T. Moyer explained: “Every man in the outfit who saw those boxcars…felt and was justified in meting out death as a punishment to the Germans who were responsible.”

Some G.I.s, however, had misgivings. “We came over here to stop this bullshit,” Corporal Henry Mills thought, “and now here we got somebody doing the same thing.” Executing prisoners was not, Lieutenant Drain believed, “the American way of fighting.”

LATER THAT APRIL 29, Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower announced Dachau’s liberation, noting that an estimated “300 SS camp guards were quickly neutralized.” In a story run in newspapers across the United States, Associated Press correspondent Howard Cowan reported how “dozens of Nazi guards fell under withering blasts of rifle and carbine fire as the soldiers, catching glimpses of the horrors within the camp, raged through its barracks for a quick cleanup.” Military censorship of the press was still the rule, and news that G.I.s had shot German guards under questionable circumstances was never reported or even suggested.

Two Signal Corps photographers, Arland B. Musser and Henry Gerzen, captured the coal yard episode on film. These graphic photos quickly made their way up the chain of command, raising disturbing questions and placing the army in an awkward position.

The Allies had postwar plans to try Axis war criminals, including German soldiers who had murdered American prisoners. Under the Geneva Convention, prisoners “must at all times be humanely treated and protected, particularly against acts

of violence,” and the unjustified killing of prisoners constituted a war crime. The Allied prosecutions would smack of hypocrisy if American soldiers were allowed to get away with similar misconduct. “America’s moral position will be undermined and her reputation for fair dealing debased if criminal conduct of a like nature by her own armed forces is condoned and unpunished…,” Eisenhower told his subordinate commanders.

On May 2, 1945, Major General Arthur White, Seventh Army chief of staff, ordered a “formal investigation of alleged mistreatment of German guards at the Concentration Camp at Dachau”; the assignment went to Lieutenant Colonel Joseph M. Whitaker, a 41-year-old lawyer. Whitaker arrived at Dachau the next day, conducted a forensic examination of the coal yard, and took sworn statements from nearly two dozen soldiers who had witnessed the killings or might have knowledge of them, ranging from General Linden to privates.

The interviews gave Whitaker the contours of what the American soldiers had done, but the men showed a poor recall of crucial details. Perhaps the chaos of April 29 overwhelmed them, or maybe some were covering for themselves or their buddies. In the coal yard, for example, Whitaker found 15 .45-caliber shell casings on the ground and “a number of 45 cal. slugs, some of which had blood on them,” embedded in the rear wall. Many G.I.s carried .45-caliber pistols or submachine guns, but no one seemed to know who had fired a .45-caliber weapon in the coal yard.

Whitaker’s investigation listed 28 killings that were potential war crimes: four in the boxcar, 17 in the coal yard, and seven near the guard tower. By June 8, 1945, Whitaker thought he had a viable case against Lieutenant Walsh, Private Pruitt, Lieutenant Busheyhead, and Sergeant Wells.

He concluded that Walsh and Pruitt had “summarily shot and killed” the four men in the boxcar. He accepted Curtin’s account and found that the 17 Germans in the coal yard had been “summarily executed under the personal supervision and orders of Lt. Walsh” and that Busheyhead had fired at these Germans. Whitaker didn’t believe the SS men had tried to rush the Americans, because the Signal Corps photos showed the Germans lying on the ground near the rear wall, with no indication any had moved toward the G.I.s. The killing of the seven by the guard tower, he determined, was an “entirely unwarranted…execution” because the Germans made “no threatening gesture or act.” He blamed Wells, who wasn’t the only soldier who had fired but the only one who admitted he had. The killing of the German wearing a Red Cross armband went unmentioned, and no attempt was made to identify the G.I.s who had stood by while inmates beat and killed guards.

Whitaker’s findings drew a sharp response from Lieutenant General Wade H. Haislip, whose command included both the 42nd and 45th divisions. Prosecuting these men would be ill-advised, Haislip argued, because it would ignore “the unbalancing effects of the horrors and shock of Dachau on combat troops already fatigued with more than 30 days continuous combat action.” Specifically, he said, “the famous train with its cars of dead bodies” and the camp’s other atrocities “would naturally produce strong mental reaction on the part of both officers and men.”

What Haislip described was temporary insanity, a potential legal defense. Under military law, a soldier was not responsible for his actions if he suffered from a mental “derangement” that impaired his ability “to distinguish right from wrong and to adhere to the right.” The impact of what these men saw on April 29 might have qualified.

After seeing the corpses in the railcars, Walsh told Whitaker, he and his men were in “a high state of excitement.” Another soldier described Walsh as “quite angry and upset,” and yet another believed Walsh’s “mind probably wasn’t clear.” Almost every after-action report and contemporaneous account describes the abominations these soldiers witnessed, especially in the railcars, and the emotions these sights stirred—predominantly rage. The shootings followed only minutes later.

These combat veterans, all too familiar with death and destruction, were completely unprepared for what they witnessed. “It is easy to read about atrocities, but they must be seen before they can be believed,” Private Porter wrote to his parents, admitting, “I even find myself trying to deny what I am looking at with my own eyes.” Sergeant James W. Creasman, a reporter for the 42nd Division newspaper, insisted “no human imagination fed with the most fantastic tales that have leaked out…could have been preparation for what they did see there.”

Even Eisenhower was unprepared. He had toured the Ohrdruf concentration camp just two weeks before the liberation of Dachau. Afterward, he wrote to Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall that “the things I saw beggar description.” The “starvation, cruelty and bestiality were so overpowering as to leave me a bit sick,” he told Marshall, and he believed that “whatever has been printed on [the camps] to date has been understatement.” Like the G.I.s at Dachau, Eisenhower felt rage. “I think I never was so angry in my life,” he told reporters.

Whitaker’s investigation showed that something had gone terribly wrong on April 29, but proving war-crimes charges at a court-martial trial was another matter. Even putting aside the mental state of these soldiers, key facts remained in dispute. The witnesses sharply disagreed on what had prompted the shootings in the coal yard and by the guard tower. Claims that the Germans along the wall had started to rush the Americans and that one at the tower had appeared to reach for a hidden pistol suggested the G.I.s may have acted in self-defense. It was not even clear who—other than Wells—had fired by the guard tower, shot at the fallen Germans, or watched inmates kill Germans.

On December 31, 1945, Colonel Charles L. Decker, deputy judge advocate for the European Theater, closed the file without charges. “It appears that there was a violation of the letter of international law in that the SS guards seem to have been shot without trial,” he admitted, but found extenuating circumstances. “In the light of the conditions which greeted the eyes of the first combat troops to reach Dachau,” he wrote, “it is not believed that justice or equity demand that the difficult and perhaps impossible task of fixing individual responsibility now be undertaken.”

In the ensuing decades, revisionists and Nazi apologists have seized on the dark side of Dachau’s liberation. The former claim the U.S. Army orchestrated a massive cover-up to hide American war crimes, and the latter try to minimize Nazi atrocities by using the G.I.s’ actions to argue that both sides fought an equally dirty war.

Howard Buechner, the army doctor who had refused to treat the wounded Germans in the coal yard, fanned the flames in 1986 when he published a book claiming American soldiers had massacred nearly 500 Germans during the liberation, a figure few historians accept. Buechner’s credibility took a hit with the declassification of Whitaker’s investigative file, which had remained classified until 1987. That file showed that Buechner had given a sworn statement in May 1945 claiming he saw only “15 or 16” Germans who had been shot by G.I.s. Colonel Sparks insisted that the 45th Division had sent an estimated several hundred Germans safely to prisoner of war camps that day, with only 30-50 killed.

For the rest of his life, Walsh offered no apologies for what he had done. “I don’t think there was any SS guy that was shot or killed in the defense of Dachau that wondered why he was killed…or couldn’t figure it out,” he said in a 1990 interview, adding, “When I get to hell, I’ll check it out and find out whether they really understood.”

The behavior of American soldiers at Dachau is not a proud moment in U.S. Army history. In Europe, these troops usually followed the rules, as attested to by the more than 400,000 German soldiers who were sent to the United States as prisoners of war, but the liberation of Dachau tarnished that record, as Nazi atrocities provoked in the G.I.s a thirst for instantaneous revenge. “To such depths does human nature sink,” army chaplain Eichorn concluded, “in the presence of human depravity.” ✯

This story was published in the December 2021 issue of World War II.