On Oct. 31, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court is scheduled to hear arguments in a pair of highly controversial cases in which, all indications suggest, a majority of the justices will rewrite the rules on who gets into institutions of higher education and will toss out the standard that has held for the past 44 years.

The issue is whether colleges and universities can put a thumb on the scale in weighing whether a letter of acceptance goes to applicants from racial or ethnic groups historically underrepresented in the student body (such as Blacks or Latinos).

Public v. Private

The justices will be hearing two cases because the rules are different for public and private institutions. Under the 14th Amendment, states must provide equal protection to all persons, so the challenge to the affirmative action policies at the University of North Carolina, a state institution, claims that it unconstitutionally discriminates against white and Asian applicants. That constitutional guarantee does not limit the actions of private schools, but there is a companion case attacking Harvard University’s admission policy claims, which also claims the impact on white and Asian students is the kind of racial discrimination that the 1964 Civil Rights law bans at schools receiving any sort of federal grants or aid money.

It will be the first time the justices rule on whether the 1964 Civil Rights Act applies to affirmative action at private schools. But for public universities these are not new arguments and goes back almost 50 years.

The justices first heard arguments in the matter in 1974, in the case of Marco DeFunis, a white student who had not gotten into the law school at the University of Washington. Early in the litigation, a Washington state trial court found enough merit in the argument against affirmative action to order the university to admit DeFunis. He was close to graduation when the justices debated the case, and a bare majority decided that, because of that, there was no real controversy remaining and so they need not issue a ruling.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

University of California v. Bakke

The Supreme Court finally addressed the issue of the constitutionality of affirmative action head on in the 1978 landmark Regents of the University of California v. Bakke. Allan Bakke decided relatively late in life that he wanted to go to medical school — a factor that led a dozen schools to reject him; despite his meeting other standards for admission, the schools felt that starting medical school at age 33, he would end up having significantly fewer years to practice medicine than would younger applicants.

Bakke sued the University of California at Davis, claiming that he would have been admitted had the school not set aside 16% of its slots for “victims of unjust societal discrimination.” Though the program did not specifically mention race, no white applicant had ever been given one of those slots. Giving special privilege to applicants in that category, Bakke argued, meant the school was violating the ban on racial discrimination in the 1964 Civil Rights Act and that he was not getting the constitutionally guaranteed equal protection of the law.

It was a dicey question for the justices, and in various combinations they issued six different opinions. Four focused on the Civil Rights Act and held that using race in the admission policy was unlawful. Four held that there was no difference between the equal protection clause and the demands of the Civil Rights Act, and that “chronic minority underrepresentation in the medical profession” justified an affirmative action admission policy.

Want MOre Controversial Supreme Court DEcisions?

Justice Lewis Powell had a unique view of the dispute, but since he managed to get one set of justices to go along with one part of his view and the other set of four to go along with another part of his conclusion, it was he who wrote the decision that became the official court pronouncement. Powell decreed that “the state certainly has a legitimate and substantial interest in ameliorating, or eliminating where feasible, the disabling effects of identified discrimination.” His opinion noted that a university could determine that a diverse student body provided everyone a better education, and so in its admission decisions could consider race and other factors that might have made an applicant unfairly disadvantaged.

But, he went on, “ethnic diversity, however, is only one element in a range of factors a university properly may consider in attaining the goal of a heterogeneous student body.” The program at Davis, with firm quotas for historically disadvantaged students, he said, went too far and so was unconstitutional.

Despite the fact that it stuck down the affirmative action plan at UC Davis, Bakke was an important holding for affirmative action because it made clear that affirmative action to help minorities was legally permissible as long as the schemes had some flexibility built in. But with six separate opinions supporting the outcome, lower courts — and colleges and universities themselves — got little guidance in knowing for sure what was allowed and what was not.

Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education

That help did not come until nine years later, and in a case that had nothing to do specifically with higher education: Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education, in 1986.

The city of Jackson, Michigan, had deliberately been hiring minority teachers to bring better racial balance to its public school faculties. When it needed to reduce the total teaching staff, it kept on the job some of those minority teachers, even though some white teachers who were let go had more seniority. White teachers sued, saying the policy denied them equal protection of the law.

Five of the nine justices agreed. In explaining why Jackson’s layoff policy was not allowed, the opinion (again by Justice Powell) laid down the standard for judging future affirmative action cases: There must be “a compelling governmental interest” in setting up the program and it must be “narrowly tailored to the achievement of that goal.” Courts in weighing the constitutional validity of such plan must use “strict scrutiny,” applying “a standard more stringent than reasonableness.”

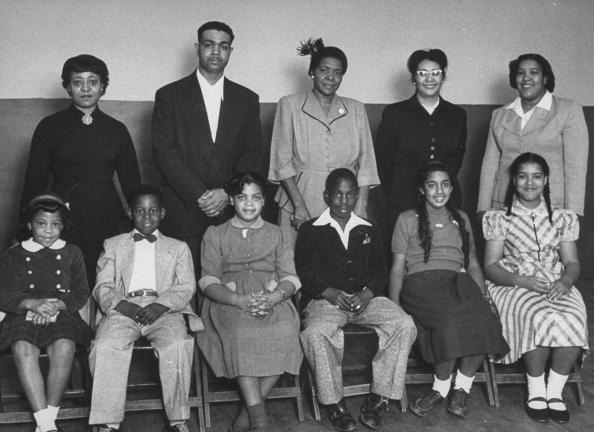

U.S. v. Fordice

Then in 1992, the high court went further. In United States v. Fordice, they found there were situations where affirmative action at public universities was not only permissible but required. By an 8-1 vote, the justices found that though Mississippi had eliminated the ban on Blacks attending its three most prestigious higher education institutions, it had not done enough to integrate the student body. Given the “segregative effects” of the state’s history of discrimination, the court said the three top-tier schools had to take affirmative action to get enroll more Black students.

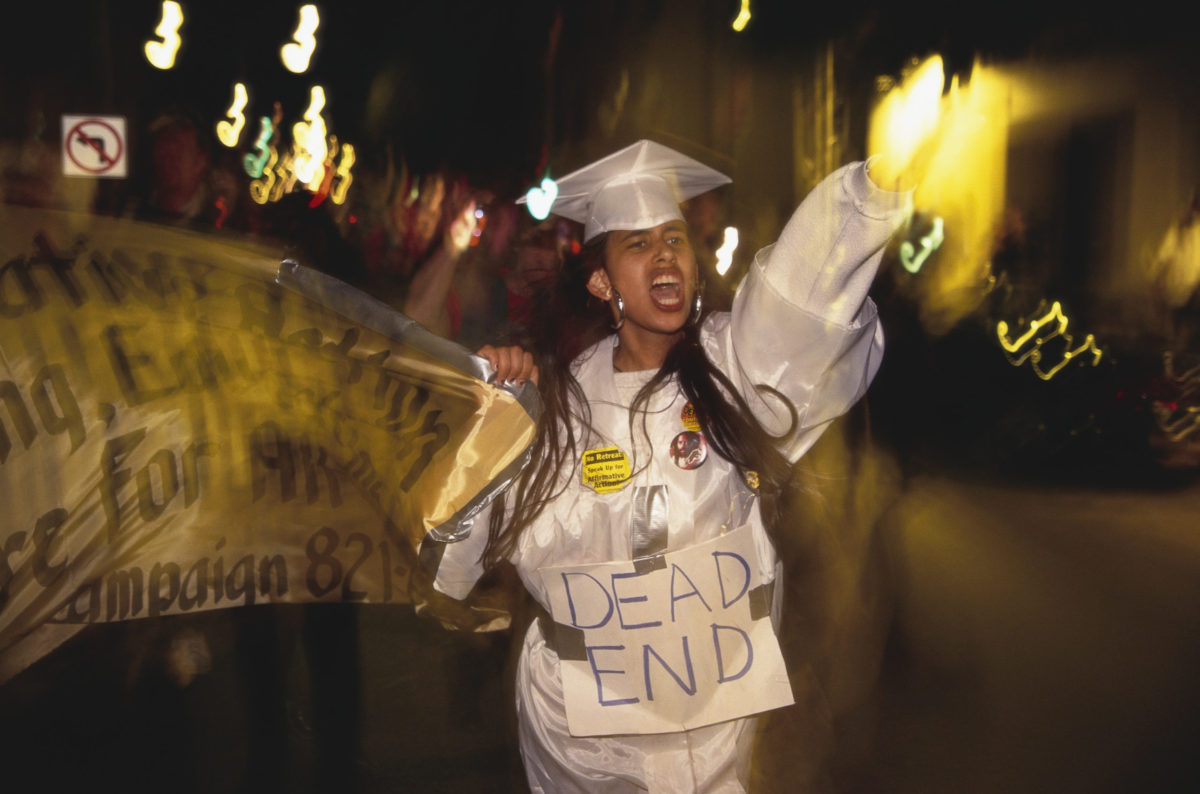

Still, opponents of affirmative action in higher education continued to attack the policy, in instance after instance insisting that the particular program did not meet the test laid out in Wygant. And the justices erected a very fine line between what schools could do and what they could not.

Affirmative Action’s Last Wins

That parsing began in 2003 with two cases with very different results handed down the same day. They OKed the affirmative action plan at the University of Michigan’s law school because it evaluated each applicant individually and the fact that an applicant could diversify the student body race was simply one factor in that evaluation.

But at the same time, they held that the admissions policy of the university’s undergraduate school was unconstitutional because it did not use such individual assessment: It simply added an extra 20 points to the evaluation score of all Black, Latino and Native American applicants. To gain admission, a propsective student needed to earn 100 points.)

In 2016, the court similarly OKed the affirmative action policy at the University of Texas.

The Beginning of the End?

But the Justices were already setting the stage for the decision that may be coming: that affirmative action plans must stop — at least at public institutions.

In the 2003 Michigan law school case, the majority opinion written by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor warned that “race-conscious admission policies must be limited in time” and said that the “court expects that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary.” And in the court’s 2016 opinion upholding the University of Texas affirmative action program, Justice Anthony Kennedy also pointed to a time when such preferences would not be allowed, telling public universities that they had an ongoing obligation “to assess whether changing demographics have undermined the need for a race-conscious policy.”

At the end of the current term, with a notably more conservative Supreme Court deciding the cases against UNC and Harvard, the age of affirmative action may well soon be over.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.