Today it seems unthinkable but in August 1863—the summer of Gettysburg and Vicksburg and the bloody New York draft riots—anybody could walk into the White House and ask to meet the president. Abraham Lincoln’s advisers warned him not to welcome strangers during wartime but he persisted. He called these meetings “taking a public opinion bath.”

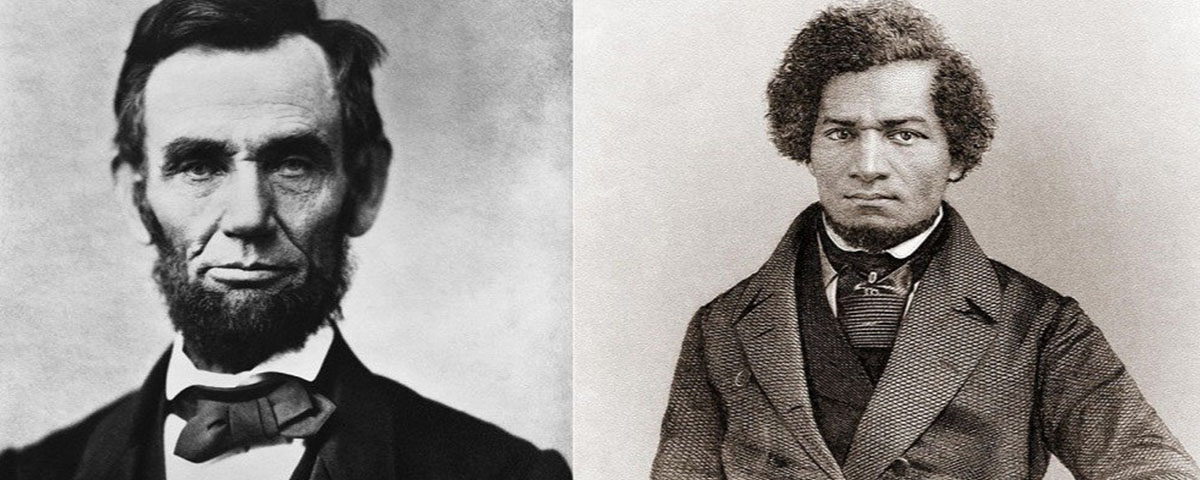

On the sweltering morning of August 10, one of Lincoln’s uninvited visitors was Frederick Douglass, a tall, burly black man dressed in a dark suit and a high-collared white shirt. He had no appointment. He simply walked in off the street, handed his business card to a secretary and joined the people waiting to see the president.

“They were white,” he recalled later, “and as I was the only dark spot among them, I expected to have to wait at least half a day. I had heard of men waiting a week.”

Born a slave in Maryland in 1818, Douglass secretly taught himself to read and write, and in 1838, he escaped and fled north to become the most famous black man of his times, an eloquent abolitionist orator, writer and newspaper publisher. He was also a radical who repeatedly criticized Lincoln for moving too slowly to free the slaves. But when the president issued the Emancipation Proclamation in late 1862, Douglass rejoiced and began recruiting black men to fight in the Union Army: “Men of Color, To Arms!”

On this day, though, he’d come to Washington to protest the army’s discrimination against black soldiers. Douglass made his case to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that morning then walked to the White House to see the president. He settled in for a long wait but within a few minutes, he heard an aide holler his name.

“Mr. Douglass!”

As Douglass elbowed his way up the crowded staircase to the president’s office, he heard somebody grumbling, “Damn it, I knew they would let the n—— through.”

Douglass ignored the slur and entered the office. Lincoln stood up and held out his hand. Douglass shook it and began to introduce himself.

The president cut him off. “Mr. Douglass, I know you. I have read about you,” he said. “Sit down. I am glad to see you.”

The two men sat and Lincoln said he’d read a speech Douglass had delivered in early 1862, lambasting the president for his “tardy, hesitating and vacillating policy” regarding emancipation. Lincoln recalled the attack without anger and admitted that he could justifiably be criticized as slow to move against slavery. But on the charge of vacillating, the president pled not guilty.

“I do not think that charge can be sustained,” Lincoln said. “I think it cannot be shown that once I have taken a position, I have ever retreated from it.”

Douglass was amazed at the president’s candor and delighted that Lincoln was speaking to him as an equal—a courtesy that white people, even abolitionists, did not always grant him.

“Mr. President, I am recruiting colored troops,” Douglass said, quickly adding that his efforts were hampered by the army’s discriminatory practices. Black soldiers were paid only about half of what white troops earned, he said, and were not promoted no matter how bravely they fought.

Lincoln listened, then sat silently for a long moment. Finally, he responded by giving his radical visitor a gentle lesson in practical politics. The reason he acted so slowly, he explained, is that a leader cannot get too far ahead of his people.

“Mr. Douglass, you know that it was with great difficulty that I could get the colored soldier—or get the colored men—into the army at all,” Lincoln said. “You know the prejudices existing against them. You know the doubt that was felt in regard to their ability as soldiers. It was necessary at first that we should make some discrimination against them: They were on trial.”

Moreover, Lincoln said, black men had a greater incentive to enlist than whites did—they were fighting for their freedom. But as black troops continued to prove their courage to the nation, he added, they would eventually receive equal pay. “I assure you, Mr. Douglass, that in the end they shall have the same pay as white soldiers.”

As for the promotion of blacks, Lincoln promised that he would sign any promotion recommended by the secretary of war.

Douglass didn’t agree with everything the president said—he saw no reason for the continued pay gap—but he was impressed with Lincoln’s honesty. He brought up reports that Confederate troops had been executing the black soldiers they’d captured, and he thanked Lincoln for his recent proclamation promising to retaliate against the executions. “In case any colored soldiers are murdered in cold blood,” Douglass said, “you should retaliate in kind.”

Again, Lincoln heard Douglass out. Again, he felt compelled to disagree. “Once begun, I don’t know where such a measure would stop,” he said.

Lincoln had, Douglass later recalled, a “tearful look in his eye and a quiver in his voice” when he spoke of his aversion to retaliatory executions. “If I could get hold of the men that murdered your troops—murdered our prisoners of war—I would execute them,” Lincoln said, “but I cannot take men that may not have had anything to do with this murdering of our soldiers and execute them.”

Before leaving the office, Douglass showed Lincoln the document he’d received when visiting Stanton that morning—a pass proclaiming him to be “a loyal free man” and “entitled to travel unmolested.” Lincoln laid the paper on a table, wrote, “I concur” and signed it.

“Douglass,” Lincoln said as his guest departed, “never come to Washington without calling on me.”

Douglass left with a new fondness for Lincoln: “I was impressed with his entire freedom from popular prejudice against the colored race.”

Four months later, Douglass addressed an abolitionist group in Philadelphia. “Perhaps you may want to know how the President of the United States received a black man at the White House,” Douglass said. “I will tell you how he received me—just as you have seen one gentleman receive another, with a hand and a voice well-balanced between a kind cordiality and a respectful reserve. I tell you, I felt big there!”

The two men met twice more. Their final encounter occurred at a White House reception after Lincoln’s second inauguration. Policemen stopped Douglass at the door and told him that blacks were not allowed to enter. Douglass protested, then sent word to the president that he was outside. Within minutes, he was admitted.

“When Mr. Lincoln saw me, his countenance lighted up,” Douglass recalled, “and he said in a voice which was heard all around: ‘Here comes my friend Douglass.’”

The president shook his friend’s hand. “I saw you in the crowd today listening to my inaugural address,” he said. Then he asked Douglass, one of America’s finest orators, what he thought of the speech. “There is no man’s opinion that I value more than yours.”

“Mr. Lincoln,” Douglass said, “that was a sacred effort.”

Originally published in the February 2011 issue of American History.