Write us!

Got something stuck

in your craw, or do you

just feel like jawing?

Shoot us an email at

wildwest@historynet.com.

Be sure to include

your name and hometown.

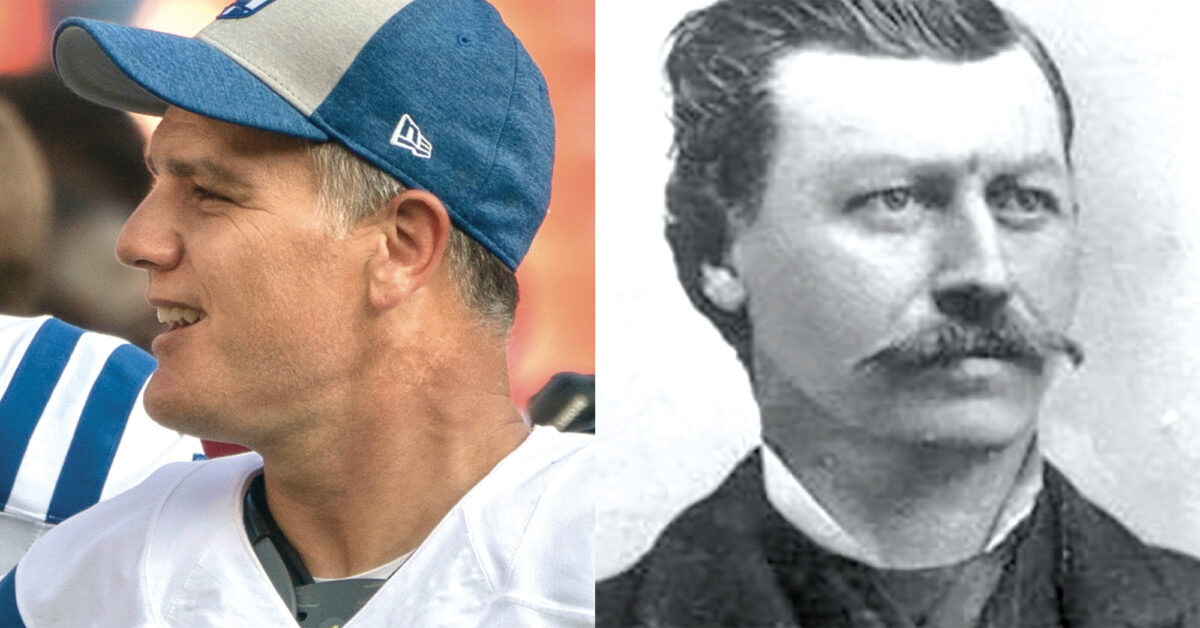

Vinatieris

As a longtime fan of the New England Patriots and a student of the Little Bighorn, I was delighted to read the piece “Custer Connection” on Adam and Felix Vinatieri in Roundup of your October 2021 issue. Although Felix (as chief musician) and all but three of the 16 enlisted men of the 7th U.S. Cavalry’s band marched with the regiment from Fort Abraham Lincoln on May 17, 1876, they did not ”follow upriver on the steamboat Far West.” They (and several other troopers) were assigned to the Powder River supply depot, which the regiment reached by land. The band’s horses were not “confiscated.” Apparently, they were reassigned to other dismounted enlisted men. Trumpeter John Martin (dispatched with the last message of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer) was not a member of the band. He was assigned to Company H of the regiment.

Felix Vinatieri’s tenure with the 7th Cavalry was not always pleasant. In August 1875, for example, he requested a discharge from the Army due to an apparent personality clash with Fort Lincoln’s adjutant and band commander, Lieutenant James Calhoun, who approved the request, which Custer endorsed. Calhoun (who died with Custer) noted that “the chief musician is not a competent person.” However, no discharge was initiated at that time. For circumstances that are unclear Felix did not return to civilian life until December 1876, months after the Little Bighorn. A well-researched, detailed profile of “Custer’s bandmaster” appeared in the June 1988 edition of the Little Big Horn Associates’ Research Review.

C. Lee Noyes

Morrisonville, N.Y.

George Hearst

Matthew Bernstein’s list of “George Hearst’s Top 10 Mines” in the February 2022 issue has a couple of misstatements about Black Hills mines. His No. 3 listing mentions a “Custer Mine” and connects it to the town of Custer, S.D. Hearst never owned a Custer Mine in the Black Hills. He and his partners did own a Custer Mine, but it was in Idaho. (As a sidenote, the town of Custer was founded around placer claims and never relied on hard rock gold mines for its existence.) In his No. 10 listing, about the Deadwood Mine, Bernstein says Hearst “quickly lost faith in it.” In fact, the Deadwood Mine sat along the Homestake Gold Belt and was absorbed into the Homestake Mining Co.’s holdings. Hearst had an interest in that mine until his death.

David Wolff

Spearfish, S.D.

Matthew Bernstein responds: Good eye! There are actually three Custer mines: one in Idaho, one in North Dakota and one in South Dakota. In “George Hearst’s Top 10 Mines” I was referring to the one in Idaho, but in a game of editorial three-card monte the Idaho Custer Mine was substituted for the South Dakota Custer Mine. In my biography George Hearst: Silver King of the Gilded Age I correctly note it was the Custer Mine in Idaho Territory that Hearst owned. Wolff is also correct about the Deadwood Mine being incorporated into the Homestake, although what I wrote about Hearst quickly losing faith in it was also true. On May 4, 1878, Hearst wrote from Deadwood to business partner J. B. Haggin: “The Deadwood Mine I found on my arrival here…very unfavorable if not disastrous. We are still continuing the tests, but my faith is gone and has been for some days, but Mr. M still thinks it will come out all right.” Mr. M was Samuel McMaster, a respected Irish mining engineer whose experience ranged from Australia to South America, Nevada and the Black Hills. Fortunately for Hearst, his faith in McMaster paid off.

In Matt Bernstein’s Top 10 list No. 1 mentions an assayer who deemed the silver from the Ophir Mine valuable. The story around Nevada City, Calif., is that the assayer was James Ott, of Ott’s Assay Office here. Hearst and partners sent down a sample of the claylike gray mud to see if it was worth anything, and it came back almost pure silver. Until that time they had been dumping it, because they were looking for gold (hence Gold Hill/Virginia City). When the news got out around town here, many miners left for Nevada, because the mines in California’s Nevada County were all established, and no new claims were being discovered.

Jim Luckinbill

Nevada City, Calif.

Matt Bernstein responds: Luckinbill’s information on James J. Ott (cousin to John Sutter of Sutter’s Mill fame) is good. Ott was among the first assayers to determine the ore being mined from the Comstock Lode was silver, which inspired Hearst (living in Nevada City at the time) to head east to Virginia City. Six months later Hearst was a millionaire.

Dreiser & James

Toward the end of Chapter 19 of Theodore Dreiser’s book A Book About Myself (1922) appears the following paragraph: “Although [Edward] Butler was an earnest Catholic, he was supposed to control and tax the vice of the city, which charge may or may not have been true. One of his sons owned and managed the leading vaudeville house in the city, a vulgar burlesque theater, at which the ticket taker was Frank James, brother of the amazing Jesse who terrorized Missouri and the Southwest as an outlaw at one time and enriched endless dime novel publishers afterward. As dramatic critic of the Globe-Democrat later I often saw him. Butler’s son, a more or less stodgy type of Tammany politician, popular with a certain element in St. Louis, was later elected to Congress.” I don’t know if this information about Frank James is well known to James’ historians, but I am passing it on in case it isn’t. Finding it in one of Dreiser’s less-read books struck me as a bit of serendipity.

Dennis Bertram

Buffalo, N.Y.

Editor responds: Frank James, twice acquitted of crimes after Jesse’s death in 1882, lived in St. Louis from the end of the 19th century into early 20th century. He worked for several years (as usher, doorman and possibly guard) at the Standard Theater, at 7th and Walnut. Colonel Edward “Boss” Butler, who ran the St. Louis Democratic Party from about 1876 until convicted of bribery charges in 1904, owned the theater. It was operated by his son James J. Butler.